The United States Constitution, a protected document, outlines the powers of Congress, which include the ability to tax and spend for welfare and defence, borrow money, regulate commerce, establish citizenship laws, and more. The extent to which Congress can delegate its legislative powers is informed by two principles: separation of powers and due process. While the Supreme Court has sometimes declared that Congress's legislative power cannot be delegated, it has also acknowledged that Congress may delegate powers that it may rightfully exercise itself. The Necessary and Proper Clause, or Article I, Section 8, Clause 18, gives Congress the authority to create laws necessary to carry out its enumerated powers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Legislative Powers | Vested in a Congress of the United States, which consists of a Senate and House of Representatives |

| Enumerated Powers | 18 powers, including the power to tax and spend, borrow money, regulate commerce, establish citizenship laws, and create laws to carry out the laws of the land |

| Necessary and Proper Clause | Gives Congress the authority to create laws necessary to carry out the laws of the land and their enumerated powers |

| Impeachment Powers | The House of Representatives can bring articles of impeachment, and the Senate is responsible for the trial |

| Assembly | Congress must assemble at least once a year, with each house keeping a journal of its proceedings |

| Due Process | The separation of powers and due process undergird delegations to administrative agencies |

Explore related products

$18.55 $27.95

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

Power to tax and spend

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to tax and spend. This is outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, also known as the Spending Clause:

> "The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States."

The Origination Clause, found in Article I, Section 7, Clause 1, stipulates that all bills for raising revenue must originate in the House of Representatives, although the Senate may propose amendments. The Army Clause, in Article I, Section 8, Clause 12, limits to two years the time a congressional appropriation to raise and support the army can remain in effect.

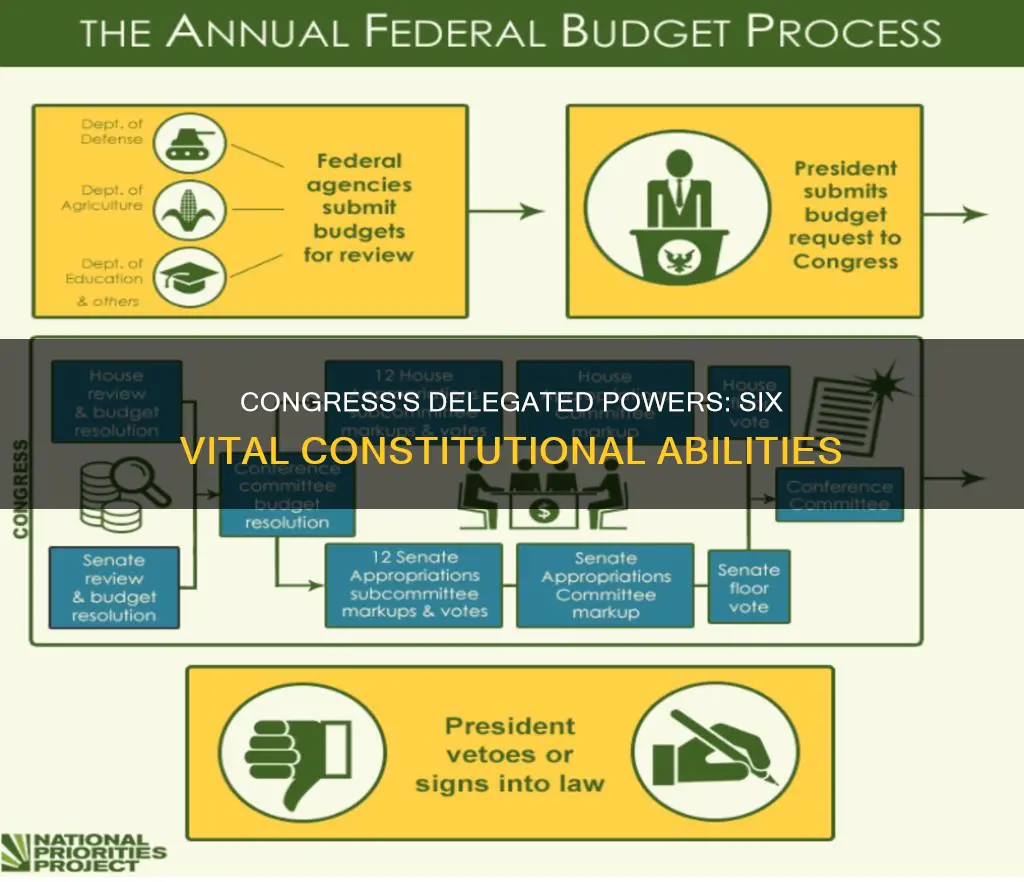

Congress must authorise by law both the collection of government revenues and their expenditure before executive branch agencies are allowed to spend money. Congress has chosen to fund the government on an annual basis, complying with the Constitution's two-year time limit on appropriations to raise and support the army. Congress also publishes information on its budgetary decisions through reports by legislative support agencies and hearings.

The Supreme Court's early Spending Clause case law culminated in 1937 with an embrace of a relatively expansive view of Congress's power to tax and spend in aid of the general welfare. The Court has repeatedly stated that, by allocating federal funds and attaching conditions to those funds, Congress's authority to attach conditions to federal funds derives, in part, from the Necessary and Proper Clause. The Court today judges the constitutional validity of federal spending using five factors:

- Congress must unambiguously identify conditions attached to federal funds.

- Congress must refrain from offers of funds that coerce acceptance of funding conditions.

- Spending must be in pursuit of the general welfare.

- Conditions on federal funds must relate to the federal interest in a program.

- A funding condition may not induce conduct on the part of the funds recipient that is itself unconstitutional.

Deadly Dose: Xanax Pills and Overdose Risk

You may want to see also

Authority to regulate commerce

The Commerce Clause, outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, grants Congress the authority to "regulate commerce with foreign nations, among states, and with the Indian tribes". This clause has been interpreted broadly, with the Supreme Court holding that Congress can regulate intrastate activity if it is part of a larger interstate commercial scheme. This interpretation was expanded in 1905, when the Supreme Court affirmed that Congress had the power to regulate local commerce, provided that it could become part of interstate commerce involving the movement of goods and services.

However, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court attempted to limit Congress's power by adopting a more conservative interpretation of the Commerce Clause. In this case, the defendant argued that the federal government did not have the authority to regulate firearms in local schools. The Supreme Court agreed, stating that Congress could only regulate the channels of commerce, the instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce.

Despite this, the Gonzales v. Raich case saw a return to a more liberal interpretation, with the Court upholding federal regulation of intrastate marijuana production. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was also challenged under the Commerce Clause in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), with the Court ruling that the individual mandate requiring the purchase of health insurance could not be enacted under the Commerce Clause as it regulated inactivity rather than commercial activity.

The Commerce Clause has been viewed as both a grant of congressional authority and a restriction on state power. While it gives Congress broad power to regulate interstate commerce, it also restricts states from impairing interstate commerce. The interpretation of the word "commerce" has been debated, with some arguing it refers to trade or exchange, while others contend that it describes a broader scope of commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states.

The Constitution's Amendments: A Dynamic History

You may want to see also

Establish citizenship laws

Article I, Section 8 of the US Constitution grants Congress the power to "establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization". This clause, known as the Naturalization Clause, gives Congress the exclusive authority to determine the conditions under which foreign nationals may become US citizens. This power is independent of the states, which cannot impose their own requirements for citizenship.

The Naturalization Clause has been interpreted by the Supreme Court as vesting exclusive power in Congress to establish rules for naturalization and citizenship. The Court has upheld this interpretation in cases such as *United States v. Wong Kim Ark* (1898), *Chirac v. Lessee of Chirac* (1817), and *Takahashi* (1948). These cases affirmed that Congress has the sole authority to create laws governing the naturalization of aliens and the conditions for their admission, naturalization, and residence in the United States.

Congress's power over citizenship and naturalization is broad and flexible. While the Naturalization Clause mandates uniformity in the rules of naturalization, Congress has the discretion to set the specific criteria for citizenship. Historically, Congress has passed laws that restricted naturalization to "free white persons", later expanding eligibility to include persons of "African nativity and descent" in 1870. Exclusions based on race and ethnicity, such as the specific exclusion of "Chinese laborers" in 1882, have since been eliminated. Today, naturalization statutes require loyalty, good moral character, and generally bar subversives, terrorists, and criminals from citizenship.

Citizenship can be acquired through various means, including individual application, congressional action, or treaty provisions. Congress may also grant citizenship through a special act or collectively, such as through the naturalization of residents of an annexed territory or a territory that has become a state. Additionally, Congress has the power to revoke citizenship in certain circumstances, such as in cases of treason, desertion during wartime, evading the draft, or attempting to overthrow the government.

The Evolution of Our Constitution: Amendments and Revisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Declare war

The US Constitution grants Congress the sole power to declare war. This power is outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 of the Constitution, also known as the Declare War Clause. This clause gives Congress the authority to initiate hostilities and take other actions related to war, such as issuing letters of marque and reprisal, which allow private citizens to capture or destroy enemy property, and making rules concerning captures of enemy property on land or at sea.

Throughout history, Congress has declared war on 11 occasions, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain and World War II. While Congress has not formally declared war since World War II, it has continued to shape US military policy through appropriations and oversight, as well as by authorizing the use of military force in specific situations.

The Declare War Clause does not restrict the President's ability to take military action or use force pursuant to statutory authorization. In such cases, the President is acting within the authority delegated to them by Congress under the Declare War Clause. However, there have been controversies and disputes between Congress and the Executive Branch over the interpretation and scope of statutory authorizations, as well as debates about the President's independent authority to use military force in response to attacks on the United States.

While the President may use other constitutional powers, such as their commander-in-chief power, to deploy US forces in situations that do not amount to war, any declaration of war remains the sole power of Congress under the US Constitution.

The Constitution: Our Founding Documents and Their Legacy

You may want to see also

Raise and support armies

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to "raise and support Armies". This power is derived from Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, which outlines Congress's powers regarding war and the military.

The power to raise and support armies is one of the checks and balances on the President's war powers, including their authority as Commander-in-Chief. By controlling military funding, Congress ensures that the will of the people is considered in any war effort. This power also prevents the President from having endless resources to continue fighting, as they do not control the military's funding.

Congress has used this power to set up a system of criminal law that applies to all servicemen and reservists on inactive duty training, as well as certain civilians with special relationships to the military. This system includes its own courts, procedures, and appeals processes.

There is a two-year limit on appropriations for the army, which was inserted by the Framers out of fear of standing armies. This limit ensures that military funding is reviewed and approved regularly, providing a further check on the use of military force.

Ben Franklin's Take on the US Constitution

You may want to see also