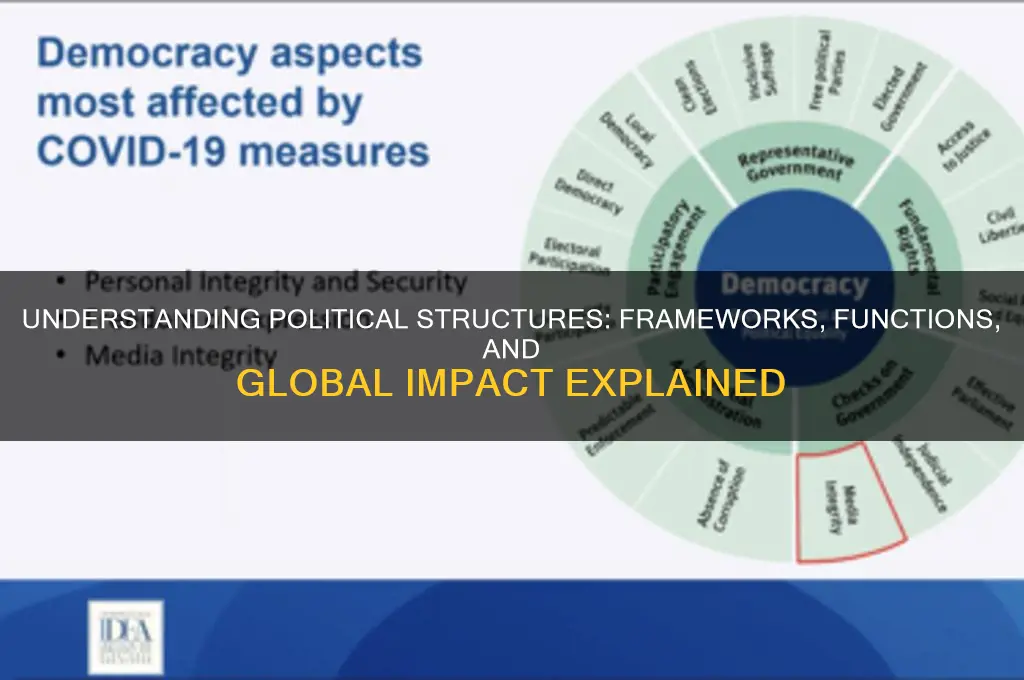

Political structures refer to the frameworks, institutions, and systems through which authority is exercised, decisions are made, and governance is organized within a society. These structures encompass formal entities such as governments, legislative bodies, and judicial systems, as well as informal networks and power dynamics that influence political processes. They define how power is distributed, how policies are formulated and implemented, and how citizens participate in or are excluded from political life. Political structures vary widely across cultures and historical periods, ranging from democratic systems that emphasize representation and accountability to authoritarian regimes that centralize control. Understanding these structures is essential for analyzing how societies manage conflict, allocate resources, and address collective challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Formal and informal frameworks that organize political power and governance. |

| Types | Unitary, Federal, Confederate, Parliamentary, Presidential, Hybrid. |

| Power Distribution | Centralized (Unitary), Decentralized (Federal), Shared (Confederate). |

| Head of State | Monarch, President, Prime Minister, or Collective Leadership. |

| Legislative Branch | Unicameral (Single House), Bicameral (Two Houses). |

| Executive Branch | Head of Government (President/Prime Minister) and Cabinet. |

| Judicial Branch | Independent Courts, Constitutional Courts, Administrative Tribunals. |

| Electoral System | First-Past-The-Post, Proportional Representation, Mixed Systems. |

| Political Parties | Multi-Party, Two-Party, Dominant-Party, One-Party Systems. |

| Citizen Participation | Direct Democracy (Referendums), Representative Democracy (Elections). |

| Rule of Law | Equality before the law, Protection of rights, Constitutional supremacy. |

| Accountability | Checks and balances, Transparency, Media freedom. |

| Examples | USA (Presidential Federal), UK (Parliamentary Unitary), EU (Supranational). |

| Stability | Depends on institutions, economic conditions, and social cohesion. |

| Globalization Impact | Increasing interdependence, rise of supranational structures (e.g., UN). |

| Technological Influence | Digital governance, e-voting, social media in political mobilization. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Forms of Government: Examines systems like democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes

- Political Institutions: Analyzes roles of legislatures, executives, judiciaries, and bureaucratic bodies

- Power Distribution: Explores federal, unitary, and confederal systems in governance

- Political Parties: Studies their functions, ideologies, and influence on policy-making

- Electoral Systems: Compares methods like proportional representation, first-past-the-post, and ranked-choice voting

Forms of Government: Examines systems like democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes

Political structures define how power is distributed, exercised, and maintained within a society. Among the most prominent forms are democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes, each with distinct mechanisms and implications for governance. Democracy, for instance, vests power in the hands of the people, either directly or through elected representatives. This system thrives on principles like majority rule, minority rights, and periodic elections. Examples include the United States, India, and Germany, where citizens actively participate in shaping policies and holding leaders accountable. However, democracies often face challenges such as polarization, slow decision-making, and the influence of special interests, which can undermine their effectiveness.

In contrast, monarchies concentrate power in a single individual or family, often passed down through hereditary succession. While some monarchies, like those in the United Kingdom or Japan, are largely ceremonial and coexist with democratic institutions, others retain significant political authority. Absolute monarchies, such as Saudi Arabia, wield unchecked power, limiting public participation and often prioritizing tradition over modernity. This form of government can provide stability but risks stagnation and resistance to reform, as power remains insulated from popular will.

Oligarchies, another form of governance, are characterized by power resting in the hands of a small, privileged group, often defined by wealth, family ties, or military control. Historically, oligarchies have emerged in societies like ancient Sparta or modern-day Russia, where a narrow elite dominates political and economic spheres. This system can lead to inequality and exploitation, as decisions favor the few at the expense of the many. However, oligarchies can also foster efficiency and swift decision-making, particularly in times of crisis, though at the cost of inclusivity and fairness.

Authoritarian regimes, meanwhile, prioritize state control and suppression of dissent, often under a single leader or party. Examples include North Korea, China, and historically, Nazi Germany. These regimes maintain power through censorship, surveillance, and coercion, limiting individual freedoms and political opposition. While authoritarianism can achieve rapid development and stability, as seen in China’s economic growth, it comes at the expense of human rights and long-term societal resilience. The lack of accountability and transparency often leads to corruption and abuse of power, making this system inherently fragile despite its surface strength.

Understanding these forms of government requires examining their trade-offs: democracy’s inclusivity versus inefficiency, monarchy’s stability versus rigidity, oligarchy’s focus versus inequality, and authoritarianism’s control versus oppression. Each system reflects societal values, historical contexts, and power dynamics, shaping the lives of citizens in profound ways. By studying these structures, one can better navigate the complexities of governance and advocate for systems that balance authority with accountability, ensuring a just and equitable society.

Do Politics Ajeet Bharti: Unveiling the Impact and Influence

You may want to see also

Political Institutions: Analyzes roles of legislatures, executives, judiciaries, and bureaucratic bodies

Political institutions form the backbone of governance, each playing a distinct role in shaping policies, enforcing laws, and maintaining order. Among these, legislatures stand as the voice of the people, tasked with crafting laws that reflect societal needs and values. Consider the U.S. Congress or the UK Parliament—these bodies debate, amend, and pass legislation, ensuring diverse perspectives are considered. However, their effectiveness hinges on representation and accountability; a legislature disconnected from its constituents risks becoming a tool for special interests rather than a guardian of public welfare.

Executives, on the other hand, are the engines of action, translating legislative intent into tangible outcomes. Presidents, prime ministers, and governors wield significant power, from appointing officials to directing foreign policy. For instance, the U.S. President’s ability to issue executive orders allows for swift action but also raises concerns about overreach. The executive’s dual role as both administrator and symbol of national unity demands a delicate balance between decisiveness and restraint, lest it undermine democratic checks and balances.

Judiciaries serve as the guardians of justice, interpreting laws and ensuring their constitutionality. Courts, from local tribunals to supreme bodies like the U.S. Supreme Court, provide a critical check on legislative and executive power. Their independence is paramount; a judiciary influenced by political pressures risks eroding public trust. For example, landmark rulings like *Brown v. Board of Education* demonstrate the judiciary’s power to drive societal change, but this role requires impartiality and a commitment to upholding the rule of law.

Bureaucratic bodies, often overlooked, are the administrative machinery that keeps governments running. Agencies like the FDA or EPA implement policies, regulate industries, and provide essential services. While bureaucracies ensure consistency and expertise, they can also become bloated and inefficient. Striking a balance between efficiency and accountability is crucial; transparent processes and clear mandates can mitigate the risks of bureaucratic inertia or overreach.

In practice, these institutions must collaborate to function effectively. Legislatures set the agenda, executives execute it, judiciaries ensure fairness, and bureaucracies manage the details. However, their interdependence also creates friction. For instance, legislative gridlock can paralyze executive action, while judicial activism may provoke backlash. To navigate these dynamics, leaders must foster dialogue, prioritize transparency, and respect institutional boundaries. Ultimately, the strength of political institutions lies not in their individual power but in their collective ability to serve the public good.

Is Cook Political Report Biased? Analyzing Its Neutrality and Accuracy

You may want to see also

Power Distribution: Explores federal, unitary, and confederal systems in governance

Political structures define how power is distributed and exercised within a state, and three primary systems dominate this landscape: federal, unitary, and confederal. Each system offers distinct mechanisms for balancing authority between central and regional governments, shaping the dynamics of governance in profound ways. Understanding these models is crucial for analyzing stability, efficiency, and representation in political systems worldwide.

Consider the federal system, where power is shared between a central authority and constituent political units, such as states or provinces. The United States and Germany exemplify this structure, with written constitutions delineating the responsibilities of each level. In practice, this means that while the federal government handles national defense and foreign policy, states retain autonomy over education, healthcare, and local infrastructure. This division fosters localized decision-making, but it can also lead to policy inconsistencies and jurisdictional conflicts. For instance, the U.S. healthcare system varies significantly across states, reflecting diverse priorities and resources. A key takeaway here is that federalism thrives on compromise, requiring constant negotiation between levels of government.

In contrast, unitary systems concentrate power in a single, central authority, with regional or local governments exercising only delegated powers. The United Kingdom and France operate under this model, where Parliament or the National Assembly holds supreme authority. This structure ensures uniformity in policy implementation, making it efficient for large-scale initiatives like national transportation networks or standardized education curricula. However, it risks neglecting regional diversity and local needs. For example, rural communities in France often feel marginalized by policies crafted in Paris. Advocates of unitary systems argue that centralized control minimizes redundancy and streamlines governance, but critics warn of potential authoritarianism if checks and balances are weak.

Confederal systems represent the opposite extreme, where power resides primarily with independent states or regions that choose to delegate limited authority to a central body. The European Union is a modern example, where member states retain sovereignty but collaborate on issues like trade and migration. This model prioritizes regional autonomy, but it often struggles with decision-making efficiency. The EU’s consensus-driven approach can lead to gridlock, as seen in protracted negotiations over fiscal policies. Confederations are ideal for preserving cultural and political identities but require strong mutual trust and shared goals to function effectively.

When evaluating these systems, consider the trade-offs between autonomy and cohesion. Federalism balances local and national interests but demands robust institutions to manage conflicts. Unitary systems prioritize uniformity and efficiency but risk alienating diverse populations. Confederations champion regional sovereignty but often lack the decisiveness needed for rapid action. The choice of structure depends on historical context, cultural values, and the desired balance between unity and diversity. For policymakers and citizens alike, understanding these dynamics is essential for designing or reforming governance frameworks that meet societal needs.

Combating Corruption: Effective Strategies to Reduce Political Bribes and Promote Integrity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Parties: Studies their functions, ideologies, and influence on policy-making

Political parties are the backbone of modern democratic systems, serving as intermediaries between the state and the citizenry. Their primary function is to aggregate interests, mobilize voters, and compete for political power. By organizing individuals with shared ideologies, parties simplify the political landscape, making it easier for voters to make informed choices. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States emphasizes social welfare and progressive taxation, while the Republican Party prioritizes limited government and free-market principles. These distinct platforms help voters align their personal beliefs with a party’s agenda, fostering political engagement.

Studying the ideologies of political parties reveals their core values and policy priorities, which directly influence governance. Ideologies act as guiding frameworks, shaping how parties approach issues like healthcare, education, and foreign policy. For example, socialist parties advocate for collective ownership of resources and robust social safety nets, whereas conservative parties often champion individualism and market-driven solutions. These ideological differences are not merely theoretical; they translate into tangible policies. A party’s ideology determines whether it will invest in public healthcare or deregulate industries, illustrating the profound impact of ideology on policy-making.

The influence of political parties on policy-making is both direct and indirect. Directly, parties in power draft and enact legislation that reflects their manifesto promises. Indirectly, they shape public discourse, set the political agenda, and influence judicial appointments. Consider the Affordable Care Act in the U.S., a policy driven by Democratic Party ideals of expanding healthcare access. Conversely, tax cuts under Republican administrations reflect their commitment to reducing government intervention. Parties also wield influence through lobbying, coalition-building, and strategic alliances, ensuring their ideologies permeate policy decisions even when out of power.

To understand the practical role of political parties, examine their internal structures and decision-making processes. Parties operate through hierarchies, with leaders, committees, and grassroots members each playing distinct roles. Leaders articulate the party’s vision, while committees draft policies and strategies. Grassroots members mobilize support and provide feedback, ensuring the party remains responsive to its base. For instance, the Labour Party in the U.K. relies on trade unions for support, which influences its pro-worker policies. This internal dynamics highlight how parties balance ideological purity with political pragmatism to maintain influence.

In conclusion, political parties are not merely vehicles for winning elections; they are institutions that shape societies through their functions, ideologies, and policy influence. By studying them, we gain insights into how political structures operate and how citizens can engage meaningfully in democracy. Whether through voting, activism, or policy advocacy, understanding parties empowers individuals to navigate and influence the political landscape effectively.

Mastering Polite Client Follow-Ups: Strategies for Effective and Respectful Communication

You may want to see also

Electoral Systems: Compares methods like proportional representation, first-past-the-post, and ranked-choice voting

Electoral systems are the backbone of democratic processes, shaping how votes translate into political representation. Among the most prominent methods are proportional representation (PR), first-past-the-post (FPTP), and ranked-choice voting (RCV). Each system carries distinct implications for party dynamics, voter engagement, and governance outcomes. Understanding their mechanics and trade-offs is essential for evaluating their suitability in different political contexts.

Proportional representation aims to allocate legislative seats in proportion to the vote share each party receives. For instance, if Party A secures 30% of the national vote, it would ideally win roughly 30% of the seats in parliament. This system fosters minority representation and encourages coalition-building, as seen in countries like the Netherlands and Sweden. However, PR can lead to fragmented legislatures and unstable governments, particularly in deeply polarized societies. Practical implementation often involves setting a minimum vote threshold (e.g., 5%) to prevent tiny parties from gaining seats and complicating governance.

In contrast, first-past-the-post is a winner-takes-all system where the candidate with the most votes in a constituency wins the seat, regardless of whether they achieved a majority. This method, used in the U.K. and U.S., tends to produce strong majority governments and simplify voter choices. However, it frequently results in significant vote wastage and underrepresentation of smaller parties. For example, in the 2019 U.K. general election, the Liberal Democrats won 11.6% of the vote but only 1.6% of the seats. Critics argue that FPTP discourages voter turnout in "safe" constituencies, where the outcome is predictable.

Ranked-choice voting introduces a more nuanced approach by allowing voters to rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate achieves a majority of first-choice votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed to the remaining candidates based on second choices. This process continues until one candidate secures a majority. RCV, used in cities like New York and countries like Australia for certain elections, reduces the "spoiler effect" and encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. However, it can be more complex for voters and administrators, requiring careful ballot design and education campaigns to ensure clarity.

When choosing an electoral system, policymakers must weigh trade-offs between representation, stability, and simplicity. PR excels in inclusivity but risks fragmentation, FPTP prioritizes decisiveness at the cost of fairness, and RCV balances majority rule with minority consideration but demands greater voter engagement. For instance, a country with a history of ethnic or regional divisions might favor PR to ensure all groups have a voice, while a stable two-party system might opt for FPTP to maintain efficiency. Implementing RCV could be a middle ground, particularly in local elections where experimentation is less risky. Ultimately, the choice of system should align with a nation’s political culture, societal needs, and democratic goals.

Understanding Political Entities: Definitions, Types, and Global Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political structures refer to the organizational frameworks, institutions, and systems through which political power is exercised, decisions are made, and governance is carried out within a society or state.

The main types include democracies, monarchies, dictatorships, theocracies, and oligarchies, each differing in how power is distributed and who holds authority.

Political structures shape how laws are created, policies are implemented, and resources are allocated, determining the relationship between the government and its citizens.

Yes, political structures can evolve due to factors like revolutions, reforms, social movements, or shifts in power dynamics within a society.

Political structures are crucial as they define the rules of governance, ensure stability, protect rights, and provide mechanisms for resolving conflicts and representing public interests.