Political prisoners' newspapers are clandestine publications produced and distributed by individuals incarcerated for their political beliefs, activities, or affiliations. Often created under harsh conditions and at great personal risk, these newspapers serve as vital tools for resistance, solidarity, and communication. They provide a platform for prisoners to share their experiences, advocate for their rights, and raise awareness about political repression and social injustices. These publications also play a crucial role in maintaining morale among prisoners and their supporters, fostering a sense of community, and mobilizing external activism. Despite facing censorship, confiscation, and punishment, political prisoners' newspapers remain a powerful expression of resilience and the enduring human spirit in the face of oppression.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Newspapers or publications created by or for political prisoners, often clandestinely, to share information, organize resistance, or express dissent. |

| Purpose | To provide a voice for political prisoners, raise awareness about their conditions, and advocate for their rights. |

| Content | Includes articles, essays, poetry, letters, and news about prison conditions, political struggles, and solidarity messages. |

| Distribution | Often circulated secretly within prisons, smuggled out to the public, or published externally by supporters. |

| Historical Examples | The Angry Brigade (UK, 1970s), The Black Panther (USA, 1960s-1970s), The Voice of Political Prisoners (South Africa, Apartheid era). |

| Challenges | Censorship, confiscation by authorities, risk of punishment for writers and distributors. |

| Significance | Acts as a tool for resistance, preserves the history of political struggles, and fosters solidarity among prisoners and activists. |

| Modern Examples | Digital platforms and blogs by political prisoners or their supporters, often facing internet censorship in authoritarian regimes. |

| Legal Status | Often considered illegal or subversive in authoritarian regimes, protected under freedom of expression in democratic societies. |

| Impact | Inspires public support for political prisoners, documents human rights abuses, and contributes to broader social and political movements. |

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of political prisoner newspapers

The concept of political prisoner newspapers emerged as a clandestine yet powerful tool for resistance and solidarity, often born in the harsh conditions of incarceration. One of the earliest examples dates back to the late 19th century, during the Tsarist regime in Russia. Prisoners in the Peter and Paul Fortress, including members of the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) movement, secretly produced handwritten newsletters to share revolutionary ideas and maintain morale. These makeshift publications were circulated discreetly, using scraps of paper and improvised ink, demonstrating the resourcefulness of those under oppression. This historical precedent underscores the enduring human need to communicate, organize, and resist even in the most restrictive environments.

Analyzing the evolution of these newspapers reveals a pattern of adaptation to changing political landscapes. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), prisoners in Franco’s concentration camps created underground publications like *Umbría* and *Reunir*. These newspapers served dual purposes: they provided a platform for political education and acted as a lifeline for prisoners facing isolation and dehumanization. The content often included poems, essays, and news from the outside world, smuggled in by sympathetic guards or visitors. This period highlights how political prisoner newspapers became not just instruments of resistance but also cultural artifacts that preserved the dignity and identity of their creators.

A comparative study of such newspapers across different regimes shows striking similarities in their objectives despite varying contexts. For instance, during South Africa’s apartheid era, prisoners on Robben Island produced *The Medium*, a newsletter that critiqued prison conditions and reinforced the struggle against racial oppression. Similarly, in Pinochet’s Chile, prisoners in the Estadio Nacional camp created *El Cordel*, a handwritten newspaper that circulated among detainees. Both examples illustrate the universal role of these publications in fostering unity, documenting abuses, and challenging authoritarian narratives. Their clandestine nature often heightened their impact, as they became symbols of defiance and hope.

To understand the practical mechanics of these newspapers, consider the steps involved in their creation and distribution. Prisoners typically relied on limited resources: stolen paper, makeshift pens crafted from twigs or metal, and hidden spaces for writing. Messages were often encoded to evade detection, with symbols or metaphors replacing explicit political statements. Distribution required ingenuity—newspapers were passed during meals, hidden in clothing, or exchanged during forced labor. These methods, while risky, ensured that the voices of the oppressed reached both fellow prisoners and, occasionally, the outside world. Such ingenuity transformed the act of publishing into an act of rebellion.

In conclusion, the historical origins of political prisoner newspapers reveal a profound intersection of creativity, resilience, and resistance. From Tsarist Russia to apartheid South Africa, these publications emerged as vital tools for survival and solidarity. Their legacy reminds us of the indomitable human spirit and the power of communication to challenge injustice. Studying these origins not only enriches our understanding of political resistance but also inspires contemporary movements fighting for freedom and dignity.

Understanding Political Harassment: Tactics, Impact, and Legal Implications

You may want to see also

Role in resistance and activism

Political prisoners’ newspapers serve as clandestine lifelines, amplifying voices silenced by oppressive regimes. These publications, often handwritten or crudely printed, circulate within prisons or are smuggled out to the public, becoming tools of resistance. They document abuses, share strategies, and sustain morale among activists, proving that even in captivity, dissent can flourish.

Consider the *Angolans’ Bulletin* during South Africa’s apartheid era. Prisoners on Robben Island secretly produced this newsletter, using it to critique prison conditions, educate fellow inmates, and maintain connections with external resistance movements. Such examples illustrate how these newspapers function not just as informational outlets but as organizational hubs, coordinating activism across prison walls.

To create or support such a publication, prioritize brevity and clarity. Use simple language to ensure accessibility, especially in multilingual environments. Include actionable updates—strike plans, legal advice, or coded messages—to empower readers. Caution: avoid explicit names or details that could endanger contributors. Instead, rely on pseudonyms and allegorical narratives to convey urgency without compromising safety.

The impact of these newspapers extends beyond immediate resistance. They archive struggles, preserving histories often erased by authoritarian narratives. For instance, the *Voice of the Voiceless*, circulated in Pinochet’s Chile, not only mobilized resistance but also became a historical record of state violence. Activists today can learn from this dual role: use these publications to both fight present oppression and document it for future accountability.

Finally, digital age adaptations offer new possibilities. Encrypted platforms and anonymous submission systems can modernize this tradition, though they must balance accessibility with security. Whether on smuggled paper or secure servers, political prisoners’ newspapers remain vital instruments, proving that even in confinement, the pen—or pixel—can challenge power.

Crafting Political Maps: The Art, Science, and Process Behind Their Creation

You may want to see also

Challenges in distribution and censorship

Political prisoners’ newspapers face a labyrinth of challenges in distribution and censorship, often operating in environments where every word is scrutinized and every copy is at risk of confiscation. These publications, crafted within the confines of detention, are lifelines for dissent, yet their journey from cell to reader is fraught with obstacles. Prison authorities frequently intercept materials, citing security concerns, while external distributors risk harassment or arrest for their involvement. The very act of sharing these newspapers becomes a clandestine operation, requiring ingenuity and resilience.

Consider the logistical hurdles: prisoners rely on limited resources—smuggled paper, makeshift pens, and covert communication channels. Once written, the content must bypass prison censors, who often redact or destroy anything deemed subversive. Even if the material escapes the facility, distributors outside face surveillance, legal repercussions, and the constant threat of raids. For instance, in countries with strict authoritarian regimes, such as Belarus or Myanmar, distributors have been detained for weeks simply for carrying unapproved literature. This cat-and-mouse game demands not just courage but also strategic planning, such as using coded language or disguising the content as personal letters.

Censorship extends beyond physical barriers, morphing into digital suppression in the modern era. Political prisoners’ writings, when shared online, are targeted by algorithms and state-sponsored trolls. Platforms like Facebook or Twitter, under pressure from governments, may flag or remove posts containing "sensitive" material, effectively silencing voices already marginalized. To counter this, activists employ encryption tools like Signal or ProtonMail and decentralized platforms like Mastodon. However, these measures require technical literacy, which not all prisoners or their supporters possess. The digital divide exacerbates the challenge, leaving many reliant on traditional, riskier methods.

A comparative analysis reveals that distribution challenges vary by region. In democratic societies, while censorship is less overt, legal loopholes and corporate compliance with government requests still hinder dissemination. For example, in the U.S., prison authorities often invoke "security" to ban publications, even those discussing systemic injustices. Conversely, in autocratic states, the risks are more brutal: distributors face torture, indefinite detention, or even execution. Despite these disparities, a common thread persists: the act of distributing political prisoners’ newspapers is inherently an act of defiance, a refusal to let oppression silence truth.

To navigate these challenges, practical strategies are essential. First, establish a network of trusted distributors, both within and outside prison walls, ensuring redundancy in case some are compromised. Second, leverage international solidarity by partnering with human rights organizations to amplify reach and provide legal protection. Third, adopt low-tech solutions like microprinting or hidden compartments in everyday items to smuggle physical copies. Finally, document every instance of censorship or harassment—this evidence can be used to advocate for policy changes or hold authorities accountable. While the path is perilous, each successful distribution chips away at the walls of oppression, proving that even in captivity, the pen remains mightier than the prison.

Understanding Metokur's Political Stance: A Comprehensive Analysis and Overview

You may want to see also

Notable examples worldwide

Political prisoners have long used newspapers as a tool for resistance, education, and solidarity, often under the most challenging circumstances. One notable example is *The Angolgate Times*, produced by political prisoners in Angola during the 1970s. This clandestine publication exposed human rights abuses and rallied international support, despite being handwritten and secretly circulated. Its existence highlights the ingenuity of prisoners in bypassing censorship and amplifying their voices, even in high-security environments.

In contrast, *The Irish People*, published by Irish republican prisoners in the 1980s, took a more institutional approach. Printed on prison typewriters and smuggled out, it served as a platform for political analysis, poetry, and calls for unity. Its distribution extended beyond prison walls, becoming a vital link between incarcerated activists and their supporters. This example underscores the dual role of such newspapers: as both a means of internal organization and a bridge to the outside world.

A more recent case is *The Voice of Tihar*, produced by inmates in India’s Tihar Jail, including political prisoners. Unlike many underground publications, this newspaper operates semi-officially, addressing issues like prison reform and human rights. Its existence demonstrates how political prisoners can leverage limited freedoms to create lasting change, even within a restrictive system. The paper’s ability to critique the system from within offers a unique model for advocacy.

Finally, *The Nelson Mandela Prison Letters* are not a newspaper in the traditional sense but merit mention for their impact. Smuggled out during his imprisonment, these writings functioned as a de facto publication, shaping global perceptions of apartheid and galvanizing the anti-apartheid movement. They illustrate how individual acts of defiance can transcend their original form, becoming powerful tools for political change. Each of these examples reveals the adaptability and resilience of political prisoners in using print media as a weapon against oppression.

Understanding the Role and Impact of MCA in Political Systems

You may want to see also

Impact on public awareness and solidarity

Political prisoners’ newspapers serve as lifelines, not just for those behind bars but for the communities they aim to reach. By disseminating firsthand accounts of injustice, resistance, and resilience, these publications bridge the isolation of imprisonment with the broader public sphere. They transform abstract notions of oppression into tangible narratives, fostering empathy and understanding among readers who might otherwise remain disconnected from the struggles of political detainees. This direct communication challenges state-controlled narratives, offering unfiltered truths that can galvanize public opinion and mobilize support.

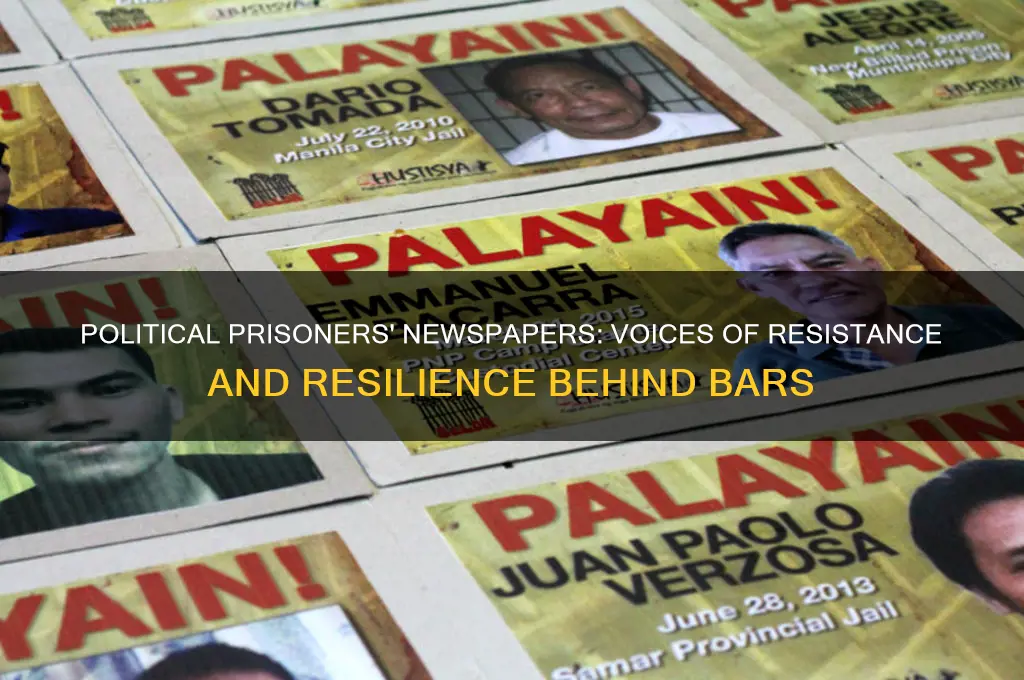

Consider the case of *Angata*, a newspaper produced by political prisoners in the Philippines during the Marcos dictatorship. Its pages, smuggled out of prison, detailed the harsh conditions inmates endured and the ideological foundations of their resistance. Distributed clandestinely, *Angata* became a rallying point for activists, students, and ordinary citizens, who saw in its words a call to action. This example underscores how such newspapers can act as catalysts for solidarity, turning passive observers into active participants in the fight for justice.

To maximize their impact, creators of political prisoners’ newspapers must employ strategic distribution methods. Physical copies, though risky, carry a tangible weight that digital formats often lack. Hidden in books, sewn into clothing, or passed hand-to-hand, these papers become artifacts of defiance. Simultaneously, leveraging digital platforms—encrypted messaging apps, social media, or dedicated websites—amplifies reach while mitigating risks. For instance, pairing QR codes with physical copies can direct readers to online archives, ensuring longevity and accessibility.

However, the effectiveness of these newspapers hinges on their ability to resonate with diverse audiences. Language, tone, and content must be tailored to engage not just activists but also the general public. Incorporating personal stories, artwork, and actionable steps—such as petitions, protests, or donation drives—can make the message more relatable and actionable. For example, including a "What You Can Do" section with specific, age-appropriate tasks (e.g., letter-writing campaigns for teens, awareness workshops for adults) can empower readers to contribute meaningfully.

Ultimately, the impact of political prisoners’ newspapers lies in their dual role as mirrors and megaphones. They reflect the realities of those silenced by the state while amplifying their voices to a global audience. By fostering public awareness and solidarity, these publications not only sustain the spirits of the imprisoned but also fuel movements that challenge systemic oppression. Their legacy reminds us that even in the darkest cells, the ink of resistance can stain the pages of history.

Understanding Political Folk: Origins, Influence, and Cultural Significance Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political prisoners' newspapers are publications created, edited, and distributed by incarcerated individuals who are imprisoned for their political beliefs, activism, or opposition to a government. These newspapers serve as a platform for political expression, advocacy, and solidarity among prisoners and their supporters.

The primary purpose is to amplify the voices of political prisoners, raise awareness about their conditions, and advocate for their rights and release. These newspapers also educate readers about political issues, foster solidarity, and challenge oppressive systems.

They are often handwritten, typed, or printed within prisons, despite strict censorship and limited resources. Distribution occurs through smuggled copies, mail to supporters outside, or publication in solidarity networks and online platforms.

The legality varies by country and prison regulations. In some cases, prisoners face severe repercussions for creating or distributing such materials, as they are often seen as subversive by authorities. However, supporters argue they are protected under freedom of expression.

They play a crucial role in keeping the struggles of political prisoners visible, mobilizing international support, and preserving their dignity and resistance. These publications also serve as historical documents of political repression and resistance.