Political organizations are structured groups or entities that aim to influence government policies, shape public opinion, and achieve specific political goals. These organizations can take various forms, including political parties, interest groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and social movements. They operate within the framework of a political system, often advocating for particular ideologies, representing specific constituencies, or addressing societal issues. Political organizations play a crucial role in democratic processes by mobilizing citizens, fostering political participation, and serving as intermediaries between the government and the public. Their activities range from campaigning and lobbying to grassroots activism, all of which contribute to the dynamic and multifaceted landscape of politics. Understanding these organizations is essential for grasping how power is distributed, decisions are made, and change is driven within societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Advocate for specific political ideologies, policies, or candidates. |

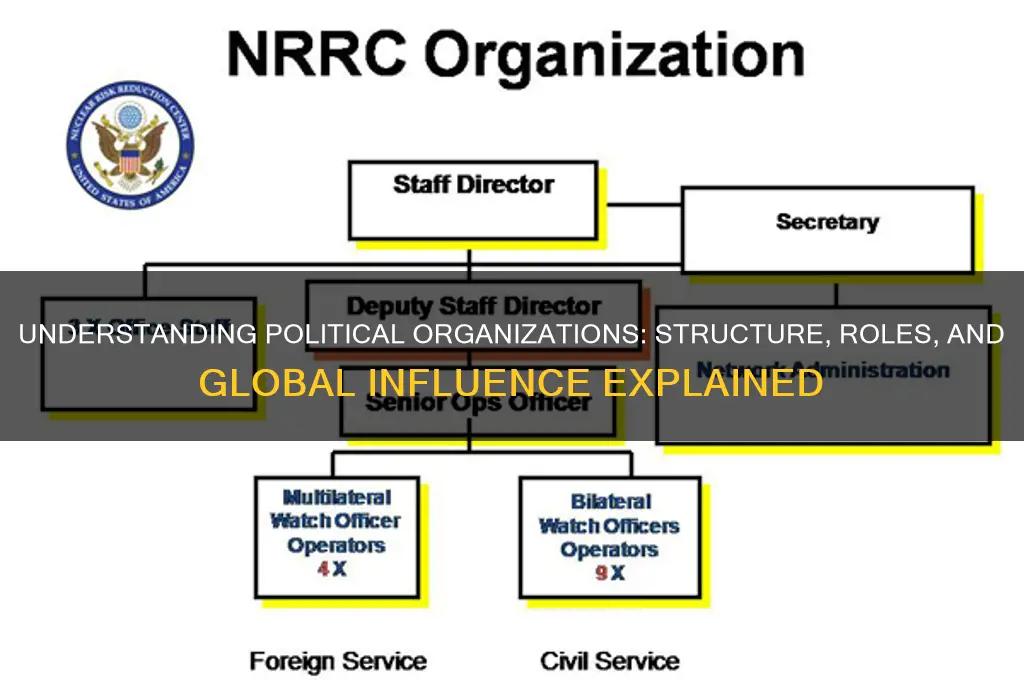

| Structure | Formal hierarchy with leadership roles (e.g., president, secretary). |

| Membership | Voluntary participation of individuals sharing common political goals. |

| Funding | Relies on donations, membership fees, grants, and fundraising activities. |

| Activities | Campaigning, lobbying, organizing rallies, and policy research. |

| Scope | Local, national, or international, depending on the organization's focus. |

| Legal Status | Registered as non-profits, NGOs, or political parties in many countries. |

| Influence | Shapes public opinion, influences legislation, and mobilizes voters. |

| Examples | Political parties, advocacy groups, think tanks, and grassroots movements. |

| Communication | Uses media, social platforms, and public events to disseminate messages. |

| Accountability | Subject to internal governance and external regulatory oversight. |

What You'll Learn

- Types of Political Organizations: Parties, interest groups, NGOs, social movements, and advocacy networks

- Structure and Leadership: Hierarchical vs. decentralized models, role of leaders, decision-making processes

- Funding and Resources: Sources of funding, resource allocation, financial transparency, and sustainability strategies

- Goals and Ideologies: Policy objectives, core beliefs, alignment with political systems, and ideological diversity

- Impact and Influence: Policy shaping, public opinion, electoral outcomes, and societal change mechanisms

Types of Political Organizations: Parties, interest groups, NGOs, social movements, and advocacy networks

Political organizations are the backbone of civic engagement, each type serving distinct functions in shaping policies and public opinion. Political parties, for instance, are the most formalized structures, acting as intermediaries between the state and citizens. They mobilize voters, nominate candidates, and govern when elected. In the United States, the Democratic and Republican parties dominate, while Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD) exemplify a multi-party system. Parties thrive on ideology, but their success hinges on adaptability—a lesson learned by the UK Labour Party’s shift from socialism to centrism under Tony Blair.

Unlike parties, interest groups operate outside electoral politics, advocating for specific causes or sectors. The National Rifle Association (NRA) in the U.S. and Greenpeace International illustrate how these groups wield influence through lobbying, litigation, and public campaigns. Their strength lies in specialization, but they face criticism for prioritizing narrow agendas over broader public interests. For instance, pharmaceutical lobbyists often oppose price controls, despite widespread public support. To maximize impact, interest groups must balance advocacy with transparency, avoiding the perception of undue influence.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) bridge the gap between grassroots activism and institutional power. Organizations like Amnesty International and Doctors Without Borders focus on human rights and humanitarian aid, often operating across borders. NGOs rely on funding from donors, governments, and the public, which can limit their autonomy. For example, Oxfam’s 2018 Haiti scandal highlighted the risks of prioritizing fundraising over accountability. Effective NGOs combine on-the-ground action with policy advocacy, ensuring their work translates into systemic change.

Social movements are the engines of transformative change, driven by collective action rather than formal structures. The Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. and #MeToo demonstrate how decentralized networks can challenge entrenched norms. Social media amplifies their reach, but it also fragments their focus. Movements succeed when they balance inclusivity with clear goals—a lesson from the Occupy Wall Street movement, which struggled to translate momentum into policy wins. For activists, the key is to sustain pressure while building alliances with established institutions.

Finally, advocacy networks connect diverse actors—NGOs, academics, and policymakers—to address complex issues like climate change or global health. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria exemplifies this model, pooling resources and expertise. These networks thrive on collaboration but require strong coordination to avoid duplication. For instance, the Paris Agreement emerged from a global advocacy network, yet its success depends on individual countries’ commitments. Practitioners should focus on building trust and aligning incentives to ensure collective action delivers results.

Each type of political organization has unique strengths and challenges, but their interplay drives democratic progress. Parties provide structure, interest groups amplify voices, NGOs deliver solutions, social movements inspire change, and advocacy networks foster cooperation. Understanding these distinctions empowers citizens to engage effectively, whether as voters, activists, or policymakers.

Understanding Political Barriers: Challenges to Progress and Cooperation

You may want to see also

Structure and Leadership: Hierarchical vs. decentralized models, role of leaders, decision-making processes

Political organizations, whether they operate on a local or global scale, must navigate the tension between hierarchical and decentralized structures. Hierarchical models, exemplified by traditional political parties, establish clear chains of command where decisions flow from top-level leaders to lower ranks. This structure ensures efficiency and unity of message but can stifle innovation and alienate grassroots members. In contrast, decentralized models, often seen in social movements like Black Lives Matter, distribute power across multiple nodes, fostering inclusivity and adaptability. However, this approach risks fragmentation and slower decision-making. The choice between these models hinges on the organization’s goals: hierarchical structures suit groups prioritizing discipline and rapid execution, while decentralized ones thrive in environments requiring flexibility and broad participation.

The role of leaders within these structures is equally pivotal. In hierarchical organizations, leaders act as central figures, embodying the group’s ideology and making critical decisions. Their effectiveness depends on their ability to inspire loyalty and maintain control. For instance, a party chairperson in a hierarchical political party must balance strategic vision with the demands of diverse factions. In decentralized models, leadership is often shared or rotational, with individuals stepping up based on expertise or circumstance. This approach empowers members but requires robust communication mechanisms to prevent chaos. Leaders in such settings must excel at facilitation rather than domination, guiding consensus-building processes rather than dictating outcomes.

Decision-making processes further distinguish these models. Hierarchical organizations rely on top-down directives, where leaders consult a small inner circle before issuing decisions. This method is swift but can overlook valuable insights from lower ranks. Decentralized organizations, on the other hand, employ consensus-based or majority-vote systems, ensuring broader input but at the cost of time and potential gridlock. For example, Occupy Wall Street’s general assemblies exemplified decentralized decision-making, where every participant had a voice, but meetings often stretched for hours. Organizations must tailor their decision-making processes to their scale and urgency: hierarchical methods suit crisis situations, while decentralized approaches are ideal for long-term, inclusive planning.

Practical tips for navigating these structures include hybrid models, which combine elements of both hierarchies and decentralization. For instance, a political organization might have a central leadership team for strategic decisions while delegating local campaign management to regional committees. Additionally, technology can bridge the gap between models: digital platforms enable decentralized groups to coordinate efficiently, while hierarchical organizations can use tools like surveys to gather grassroots input. Leaders should also invest in training to adapt their styles, learning to command when necessary and to step back when collaboration is key. Ultimately, the most effective political organizations are those that align their structure, leadership, and decision-making processes with their mission and context.

Understanding Workhorse Politics: The Unseen Engine of Policy and Progress

You may want to see also

Funding and Resources: Sources of funding, resource allocation, financial transparency, and sustainability strategies

Political organizations, whether parties, advocacy groups, or think tanks, rely heavily on funding to operate effectively. The sources of this funding vary widely and often dictate the organization’s reach, influence, and independence. Common sources include membership dues, donations from individuals, corporate sponsorships, grants from foundations, and, in some cases, government funding. For instance, in the U.S., political parties raise funds through grassroots campaigns, high-dollar fundraisers, and PACs (Political Action Committees), while advocacy groups like Greenpeace rely on small donations and international grants. Understanding these sources is critical, as they shape not only the organization’s financial health but also its perceived legitimacy and agenda.

Resource allocation is the strategic art of deciding where funds and assets are directed to maximize impact. Political organizations must balance immediate needs, such as campaign advertising or staff salaries, with long-term investments like policy research or grassroots organizing. A common pitfall is over-allocating resources to high-visibility activities while neglecting foundational work. For example, a political party might spend heavily on TV ads during an election cycle but underinvest in voter registration drives, which are crucial for sustained support. Effective allocation requires clear goals, data-driven decision-making, and flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances.

Financial transparency is both a moral imperative and a practical necessity for political organizations. Donors, members, and the public demand accountability, especially in an era of heightened scrutiny over political financing. Organizations that disclose their funding sources, budgets, and spending patterns build trust and credibility. For instance, the Sunlight Foundation advocates for open data in politics, setting a standard for transparency. However, achieving transparency is not without challenges. It requires robust accounting systems, regular audits, and a commitment to ethical practices, even when it means revealing uncomfortable truths about funding dependencies.

Sustainability strategies are essential for political organizations to endure beyond election cycles or short-term campaigns. Diversifying funding sources is a key tactic; relying solely on one stream, such as corporate donations, can lead to vulnerability during economic downturns or shifts in donor priorities. Building a loyal base of small-dollar donors, as seen in Bernie Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 campaigns, provides a stable foundation. Additionally, investing in digital infrastructure and grassroots networks ensures long-term engagement. Organizations must also plan for financial resilience by maintaining emergency reserves and exploring innovative revenue models, such as merchandise sales or crowdfunding initiatives. Without such strategies, even the most impactful organizations risk fading into obscurity.

Exploring Four Major Political Ideologies Shaping Global Governance

You may want to see also

Goals and Ideologies: Policy objectives, core beliefs, alignment with political systems, and ideological diversity

Political organizations are defined by their goals and ideologies, which serve as the bedrock for their actions and influence. At their core, these entities aim to shape public policy, often advocating for specific changes in governance, economics, or social structures. For instance, the Sierra Club, a prominent environmental organization, has a clear policy objective: to combat climate change through legislative action and public awareness. This goal is not just a statement but a guiding principle that informs every campaign, protest, and lobbying effort they undertake. Understanding such objectives is crucial, as they dictate the organization’s strategies and alliances, offering a roadmap for both members and observers.

Core beliefs are the ideological DNA of political organizations, often rooted in broader philosophies like liberalism, conservatism, socialism, or libertarianism. Take the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), whose core belief in individual freedoms and constitutional rights transcends partisan politics. This ideology shapes their stance on issues ranging from free speech to reproductive rights, ensuring consistency in their advocacy. However, these beliefs are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes. For example, the rise of digital privacy concerns has expanded the ACLU’s focus to include tech policy, demonstrating how core beliefs adapt while retaining their foundational essence.

Alignment with political systems is a strategic choice that determines an organization’s effectiveness. Some groups, like the National Rifle Association (NRA), align closely with specific parties or ideologies, leveraging this relationship to advance their agenda. Others, such as Doctors Without Borders, maintain neutrality, focusing on humanitarian goals regardless of political context. This alignment is not without risks; partisan associations can alienate potential supporters, while neutrality may limit influence in policy-making circles. Organizations must therefore weigh the benefits of access against the costs of perceived bias, a delicate balance that defines their long-term impact.

Ideological diversity within political organizations can be both a strength and a challenge. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), for instance, encompasses members with varying degrees of socialist thought, from reformists to revolutionaries. This diversity fosters robust debate and innovation but can also lead to internal divisions. Managing such differences requires clear communication, inclusive decision-making, and a shared commitment to overarching goals. Practical tips for fostering unity include regular town hall meetings, transparent leadership, and platforms for minority voices. When harnessed effectively, ideological diversity becomes a powerful tool for adaptability and resilience in an ever-changing political landscape.

Understanding North Korea's Political System: Juche Ideology and Authoritarian Rule

You may want to see also

Impact and Influence: Policy shaping, public opinion, electoral outcomes, and societal change mechanisms

Political organizations wield significant power in shaping the trajectory of societies, often operating behind the scenes yet leaving an indelible mark on policy, public sentiment, and electoral landscapes. Their influence is multifaceted, acting as catalysts for change or guardians of the status quo. Consider the role of advocacy groups in policy formulation: by leveraging research, lobbying, and strategic alliances, they can push specific agendas into legislative chambers. For instance, environmental organizations have successfully advocated for stricter emissions regulations, demonstrating how focused efforts can translate into tangible policy outcomes. This process, however, is not without challenges; it requires sustained engagement, evidence-based arguments, and the ability to navigate complex political ecosystems.

Shifting focus to public opinion, political organizations often serve as amplifiers of collective voices, shaping narratives that resonate with diverse audiences. Social media campaigns, grassroots movements, and targeted messaging are tools in their arsenal. Take the Black Lives Matter movement, which not only galvanized global protests but also shifted public discourse on racial justice, influencing corporate policies and media representation. Yet, the impact on public opinion is a double-edged sword; while it can foster unity, it can also polarize societies if not managed carefully. Organizations must balance advocacy with inclusivity, ensuring their messages bridge divides rather than deepen them.

Electoral outcomes are another arena where political organizations exert profound influence, often determining the balance of power. From funding campaigns to mobilizing voters, their strategies can sway elections in favor of aligned candidates. For example, labor unions have historically rallied members to support pro-worker candidates, showcasing the power of organized collective action. However, this influence is not without ethical considerations; transparency in funding and adherence to legal boundaries are critical to maintaining legitimacy. The takeaway is clear: political organizations can be kingmakers, but their methods must withstand scrutiny to preserve democratic integrity.

Lastly, the role of political organizations in driving societal change cannot be overstated. They often act as incubators for progressive ideas, pushing boundaries on issues like gender equality, climate action, or healthcare reform. The #MeToo movement, for instance, not only exposed systemic injustices but also spurred legislative changes and cultural shifts. Yet, societal change is a marathon, not a sprint. It demands persistence, adaptability, and a willingness to engage with opposing viewpoints. Political organizations must therefore adopt long-term strategies, combining advocacy with education, to embed transformative ideas into the fabric of society. Their success lies in their ability to inspire action while fostering dialogue, ensuring that change is both meaningful and sustainable.

Decoding Political Dog Whistling: Hidden Messages and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political organizations are groups or institutions formed to influence government policies, promote specific ideologies, or support political candidates. They can include political parties, interest groups, advocacy organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) focused on political issues.

The primary purpose of political organizations is to shape public policy, mobilize citizens, and advocate for specific causes or candidates. They work to represent the interests of their members or supporters and influence political decision-making processes.

While political parties focus on winning elections and gaining political power, political organizations have a broader scope, including advocacy, lobbying, and grassroots mobilization. Political organizations may or may not be affiliated with a specific party and often focus on single issues or ideological goals.

Yes, individuals can join political organizations as members, volunteers, or donors. Roles include participating in campaigns, attending meetings, advocating for policies, fundraising, and contributing to the organization’s mission through various activities.