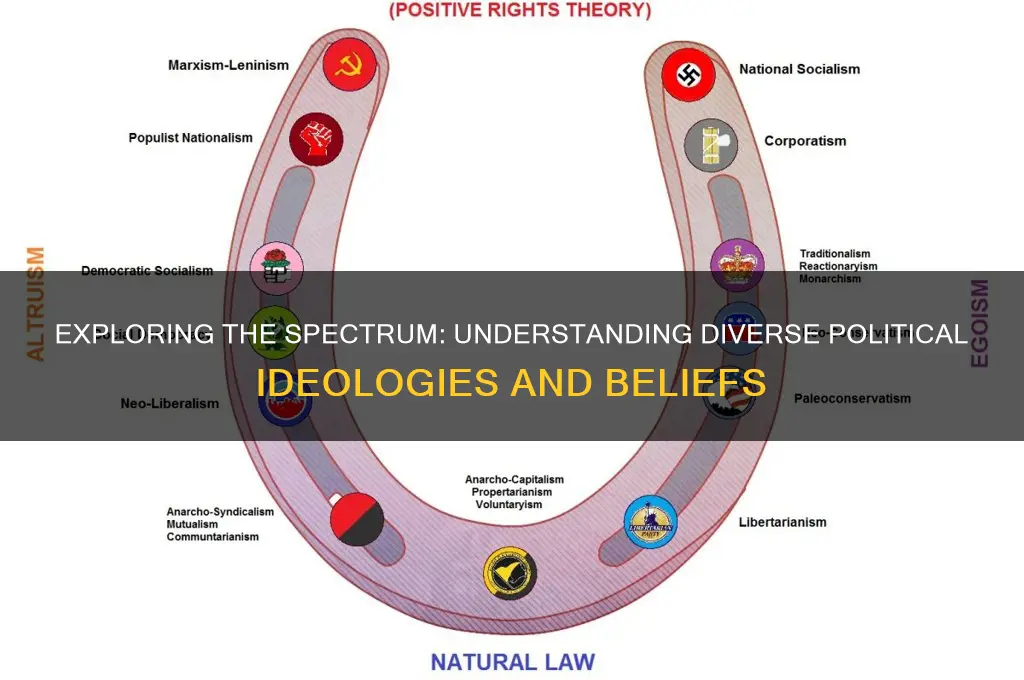

Political ideologies are comprehensive sets of ideas, principles, and beliefs that shape how individuals and groups understand and approach governance, power, and societal organization. These ideologies serve as frameworks for interpreting political events, formulating policies, and advocating for specific social, economic, and cultural structures. Ranging from conservatism, which emphasizes tradition and gradual change, to liberalism, which prioritizes individual freedoms and equality, and socialism, which advocates for collective ownership and equitable distribution of resources, each ideology offers distinct perspectives on the role of the state, the economy, and individual rights. Other significant ideologies include fascism, which promotes authoritarianism and nationalism, and environmentalism, which focuses on sustainability and ecological preservation. Understanding these ideologies is crucial for navigating the complexities of political discourse and recognizing the diverse values that underpin global and local political systems.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Liberalism: Emphasizes individual freedom, equality, democracy, and free markets as core principles

- Conservatism: Values tradition, limited government, free markets, and strong national identity

- Socialism: Advocates collective ownership, economic equality, and worker rights over capitalism

- Communism: Aims for classless society with common ownership and resource distribution

- Fascism: Prioritizes nationalism, authoritarianism, and suppression of opposition for state power

Liberalism: Emphasizes individual freedom, equality, democracy, and free markets as core principles

Liberalism, at its core, champions the individual as the cornerstone of society. This ideology posits that personal freedoms—such as speech, religion, and association—are inalienable rights that must be protected by the state. For instance, liberal democracies like the United States and Germany enshrine these freedoms in their constitutions, ensuring citizens can express themselves without fear of retribution. However, this emphasis on individual liberty often clashes with collective interests, raising questions about where to draw the line between personal freedom and societal responsibility.

Equality is another pillar of liberalism, though its interpretation varies. Liberals advocate for equality under the law and equal opportunities, not necessarily equal outcomes. For example, affirmative action policies in countries like India aim to level the playing field for historically marginalized groups, ensuring they have access to education and employment. Yet, critics argue that such measures can sometimes lead to reverse discrimination, highlighting the delicate balance liberalism must strike between fairness and equity.

Democracy, as a liberal principle, is not merely about majority rule but also about protecting minority rights. Liberal democracies employ mechanisms like checks and balances and independent judiciaries to prevent tyranny of the majority. The European Union, for instance, operates on liberal democratic principles, ensuring member states adhere to shared values of human rights and the rule of law. This approach underscores liberalism’s commitment to creating inclusive political systems that safeguard individual rights while fostering collective decision-making.

Free markets are the economic counterpart to liberalism’s political ideals, emphasizing minimal state intervention and competition as drivers of prosperity. Countries like Singapore and Sweden demonstrate how free markets can coexist with robust social safety nets, though their approaches differ. Singapore relies on a highly competitive, low-tax environment, while Sweden combines market freedoms with extensive welfare programs. These examples illustrate liberalism’s adaptability, showing that free markets can be tailored to address diverse societal needs without sacrificing economic efficiency.

In practice, liberalism’s principles often require trade-offs. For instance, prioritizing individual freedom may limit the state’s ability to regulate industries, potentially leading to environmental degradation or economic inequality. Similarly, free markets can exacerbate wealth disparities if not accompanied by redistributive policies. Thus, liberalism is not a rigid doctrine but a framework that demands constant negotiation between its core values and the realities of a changing world. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to evolve, offering a vision of society where freedom, equality, democracy, and prosperity can coexist—albeit imperfectly.

The Art of Being Polite: Mastering Respectful Communication in Daily Life

You may want to see also

Conservatism: Values tradition, limited government, free markets, and strong national identity

Conservatism, as a political ideology, anchors itself in the preservation of tradition, advocating for a society that honors its historical roots and established norms. This reverence for the past is not merely nostalgic but serves as a foundation for stability and continuity. For instance, conservative policies often prioritize maintaining traditional family structures, religious institutions, and cultural practices, viewing these as essential pillars of a functioning society. By upholding these traditions, conservatism seeks to provide a sense of order and predictability in an ever-changing world.

A core tenet of conservatism is the belief in limited government, which emphasizes minimizing state intervention in both personal and economic affairs. This principle is rooted in the idea that individuals and communities are best equipped to manage their own lives when free from excessive bureaucratic control. For example, conservatives typically oppose expansive welfare programs, arguing that they can create dependency and stifle personal responsibility. Instead, they advocate for targeted, temporary assistance that encourages self-reliance. This approach extends to regulatory policies, where conservatives often push for deregulation to foster innovation and efficiency in industries such as healthcare, energy, and education.

Free markets are another cornerstone of conservatism, reflecting a belief in the power of individual initiative and competition to drive economic prosperity. Conservatives argue that market forces, when left largely unencumbered, naturally allocate resources more efficiently than centralized planning. For instance, tax cuts and reductions in corporate regulations are common conservative prescriptions for stimulating economic growth. However, this commitment to free markets is not without caution; conservatives often stress the importance of ethical business practices and the need to protect consumers from exploitation. This balance between economic freedom and moral responsibility is a distinguishing feature of conservative economic thought.

A strong national identity is integral to conservatism, as it fosters unity and pride among citizens. This emphasis on national identity often manifests in policies that prioritize sovereignty, border security, and cultural cohesion. For example, conservatives frequently advocate for stricter immigration policies, not out of hostility toward outsiders, but from a belief that controlled borders are essential for maintaining social and economic stability. Similarly, they support initiatives that promote national heritage, such as funding for historical preservation or civic education programs. These measures aim to strengthen the bonds that tie citizens to their country, reinforcing a shared sense of purpose and belonging.

In practice, conservatism offers a framework for addressing contemporary challenges while remaining grounded in timeless principles. For individuals seeking to engage with conservative ideas, it is essential to understand the ideology’s emphasis on balance—between tradition and progress, individual freedom and collective responsibility, and national pride and global engagement. By embracing these principles, conservatives aim to build a society that is both resilient and dynamic, capable of navigating the complexities of the modern world without losing sight of its core values. This approach, while not without its critics, provides a distinct perspective on governance and societal organization that continues to shape political discourse worldwide.

The Political Church: Power, Influence, and Religious Authority in History

You may want to see also

Socialism: Advocates collective ownership, economic equality, and worker rights over capitalism

Socialism challenges the core tenets of capitalism by prioritizing collective ownership of resources and means of production. Unlike capitalist systems where private individuals or corporations control wealth generation, socialism advocates for shared ownership, often through state management or cooperative models. This shift aims to eliminate the exploitation of labor and ensure that economic benefits are distributed more equitably among society. For instance, in countries like Sweden and Norway, socialist principles are integrated into mixed economies, where key industries like healthcare and education are publicly owned, ensuring universal access and reducing wealth disparities.

To understand socialism’s appeal, consider its focus on worker rights. Under capitalism, workers often face precarious employment, wage stagnation, and limited bargaining power. Socialism seeks to empower workers by granting them greater control over their workplaces, either through direct management or collective decision-making. For example, worker cooperatives, such as Mondragon in Spain, demonstrate how employees can own and operate businesses democratically, sharing profits and responsibilities equally. This model not only fosters economic equality but also aligns with socialism’s emphasis on dignity and autonomy in labor.

However, implementing socialism is not without challenges. Critics argue that centralized control can lead to inefficiency, reduced innovation, and bureaucratic stagnation. The collapse of the Soviet Union and economic struggles in Venezuela are often cited as examples of socialism’s limitations. Yet, proponents counter that these failures were due to authoritarian governance and resource mismanagement, not socialism itself. A practical approach to socialism today involves balancing collective ownership with market mechanisms, as seen in Nordic countries, where high taxation funds robust social welfare programs without eliminating private enterprise.

For those considering socialist principles in policy or practice, start by examining local industries ripe for cooperative models, such as agriculture or retail. Encourage worker-owned businesses through tax incentives or grants, and support policies that strengthen labor unions and collective bargaining rights. Additionally, advocate for progressive taxation and public investment in education, healthcare, and infrastructure to reduce economic inequality. While socialism may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, its emphasis on collective ownership and worker rights offers a compelling alternative to capitalist disparities.

Understanding Political Rallies: Purpose, Impact, and Historical Significance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Communism: Aims for classless society with common ownership and resource distribution

Communism, at its core, seeks to dismantle societal hierarchies by abolishing private ownership of resources and establishing a classless society. This ideology posits that wealth and resources should be held in common, distributed according to need rather than accumulated by individuals or corporations. The ultimate goal is to eliminate exploitation and inequality, creating a society where everyone contributes according to their ability and receives according to their needs. This vision contrasts sharply with capitalist systems, where wealth disparities often widen, and resources are controlled by a minority.

To achieve this classless society, communism advocates for collective ownership of the means of production, such as factories, land, and natural resources. This shift requires a fundamental restructuring of economic systems, moving away from profit-driven models to ones focused on communal benefit. For instance, instead of corporations maximizing shareholder value, industries would operate to meet societal needs, ensuring essentials like food, housing, and healthcare are accessible to all. Practical steps toward this include nationalizing key industries and implementing centralized planning to allocate resources efficiently.

However, the implementation of communism has faced significant challenges. Historical examples, such as the Soviet Union and Maoist China, highlight the difficulties of balancing centralized control with individual freedoms. Critics argue that these regimes often led to authoritarianism, stifling dissent and innovation. Additionally, the absence of market mechanisms can result in inefficiencies, as seen in shortages of goods and services in some communist states. These failures underscore the importance of careful planning and adaptability when pursuing communist ideals.

Despite these challenges, communism remains a compelling ideology for those seeking to address systemic inequalities. Its focus on collective welfare and resource equity offers a stark alternative to the individualism of capitalism. For individuals or groups considering communist principles, starting small—such as through cooperatives or community-based resource-sharing programs—can provide practical insights into its potential and limitations. By examining both its theoretical promise and historical pitfalls, one can better understand how communism might contribute to a more equitable future.

Understanding Political Lobbying: Influence, Power, and Policy Shaping Explained

You may want to see also

Fascism: Prioritizes nationalism, authoritarianism, and suppression of opposition for state power

Fascism, as a political ideology, is characterized by its unwavering emphasis on nationalism, authoritarian governance, and the systematic suppression of opposition to consolidate state power. Unlike democratic systems that value pluralism and individual freedoms, fascism prioritizes the collective identity of the nation above all else, often at the expense of personal rights. This ideology emerged in the early 20th century, with Benito Mussolini’s Italy serving as its prototypical example. Mussolini’s regime, established in 1922, exemplified fascism’s core tenets: a single-party state, a cult of personality around the leader, and the use of propaganda to mobilize public support. The state, under fascism, is not a neutral arbiter but an instrument to enforce a singular vision of national greatness, often defined by ethnic, cultural, or racial exclusivity.

To understand fascism’s mechanics, consider its operational steps. First, it fosters an extreme form of nationalism, often coupled with xenophobia, to unite the population under a shared identity. Second, it establishes authoritarian rule, eliminating checks and balances and concentrating power in the hands of a leader or party. Third, it suppresses dissent through censorship, surveillance, and violence, ensuring no opposition can challenge the regime. For instance, Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler employed these tactics to devastating effect, using institutions like the Gestapo to enforce conformity and eliminate political enemies. This systematic approach ensures the state’s dominance, but at the cost of individual liberties and societal diversity.

A comparative analysis highlights fascism’s stark contrast with other ideologies. While communism seeks to abolish class distinctions and capitalism emphasizes individual enterprise, fascism focuses on national unity and state supremacy. Unlike liberalism, which values freedom and equality, fascism views these principles as secondary to the nation’s interests. This distinction is crucial: fascism’s suppression of opposition is not merely a policy but a foundational principle, designed to maintain control and eliminate threats to its monolithic vision. For example, while democratic societies tolerate and even encourage debate, fascist regimes criminalize it, viewing dissent as treasonous.

Practically, recognizing fascism’s early warning signs is essential for safeguarding democratic institutions. These include the glorification of a strong leader, the erosion of independent media, and the demonization of minority groups. Citizens must remain vigilant, as fascism often gains traction during times of economic instability or national crisis, exploiting fears and frustrations. Historical examples, such as the rise of Francisco Franco in Spain or the modern resurgence of far-right movements, demonstrate fascism’s adaptability and resilience. By understanding its mechanisms and tactics, individuals can better resist its allure and protect democratic values.

In conclusion, fascism’s prioritization of nationalism, authoritarianism, and suppression of opposition represents a dangerous ideology that undermines individual freedoms and societal pluralism. Its historical manifestations serve as cautionary tales, illustrating the consequences of unchecked state power. By studying fascism’s methods and contrasting it with other ideologies, we gain insights into its appeal and vulnerabilities. This knowledge is not merely academic but a practical tool for defending democratic principles and ensuring that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

Is Earth Day Political? Exploring Environmentalism's Intersection with Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Liberalism emphasizes individual liberty, equality under the law, and democratic governance. Core principles include free speech, free markets, human rights, and limited government intervention in personal affairs.

Conservatism values tradition, stability, and established institutions. It prioritizes limited government, free markets, strong national identity, and often advocates for a smaller welfare state.

Socialism advocates for collective or public ownership of the means of production and equitable distribution of resources. It contrasts with capitalism, which emphasizes private ownership and market-driven economies.

Fascism promotes extreme nationalism, authoritarianism, and often racial superiority. It differs from other ideologies by rejecting individualism, democracy, and socialism, favoring a totalitarian state.

Anarchism seeks to abolish all forms of hierarchical control, including the state, capitalism, and coercive authority. Its main goals are individual freedom, voluntary association, and a stateless society.