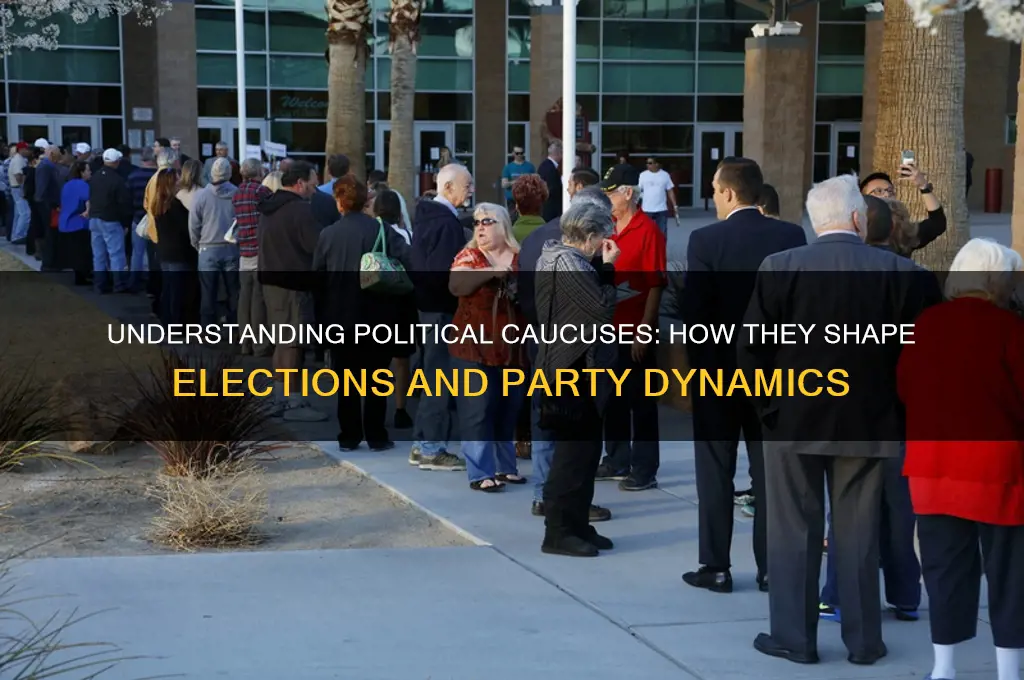

Caucuses are a fundamental yet often misunderstood component of the American political system, serving as a method for political parties to select their candidates for various offices, most notably in presidential elections. Unlike primary elections, which are administered by state governments and involve voters casting ballots at polling places, caucuses are private meetings organized by political parties where participants gather to discuss, debate, and ultimately vote for their preferred candidate. Typically held in local settings such as schools, churches, or community centers, caucuses require attendees to physically assemble and engage in a more interactive and time-consuming process. This system, while fostering grassroots engagement and direct democracy, has been criticized for its complexity, low turnout, and potential exclusion of voters who cannot commit to lengthy meetings. Despite these challenges, caucuses remain a significant tradition in states like Iowa and Nevada, playing a pivotal role in shaping the early stages of the presidential nomination process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Caucuses are local gatherings of voters within a political party to select candidates for an upcoming election, often through open discussions and consensus-building. |

| Purpose | To choose delegates who will represent the party at a national convention and influence the party's platform. |

| Participation | Open to registered voters affiliated with the specific political party holding the caucus. |

| Process | Involves group discussions, persuasion, and multiple rounds of voting to reach a consensus or majority decision. |

| Location | Held in various local venues such as schools, churches, or community centers. |

| Time Commitment | Typically longer than primary voting, often lasting several hours. |

| Privacy | Less private than primaries; participants publicly declare their support for a candidate. |

| States Using | Primarily used in states like Iowa, Nevada, and others, though their prevalence is declining. |

| Influence | Early caucuses, like Iowa, can significantly impact a candidate's momentum and media coverage. |

| Criticisms | Often criticized for low turnout, complexity, and lack of accessibility compared to primaries. |

| Trend | Many states are transitioning from caucuses to primaries due to accessibility and efficiency concerns. |

Explore related products

$22.64 $29.95

What You'll Learn

- Caucus vs. Primary: Key differences in how states nominate presidential candidates in the U.S

- Caucus Process: Steps involved, including voter gatherings, alignment, and delegate selection

- Historical Origins: Roots of caucuses in early American political party organization

- Pros and Cons: Advantages (engagement) and disadvantages (low turnout, complexity) of caucuses

- Notable Examples: Iowa caucuses and their influence on presidential election campaigns

Caucus vs. Primary: Key differences in how states nominate presidential candidates in the U.S

In the United States, the process of nominating presidential candidates varies significantly between caucuses and primaries, two distinct methods employed by different states. Caucuses are local gatherings where registered party members meet to discuss and vote for their preferred candidate, often involving multiple rounds of voting and persuasion. Primaries, on the other hand, resemble traditional elections, where voters cast secret ballots at polling stations, similar to the general election process. This fundamental difference in structure shapes the dynamics of candidate selection and voter participation.

Consider the mechanics of each system. Caucuses are typically held in schools, community centers, or private homes, and participants must physically attend and engage in the process, which can last several hours. This format favors highly motivated, ideologically driven voters but can exclude those with time constraints, such as working parents or individuals with disabilities. Primaries, however, offer greater accessibility, allowing voters to cast their ballots during a broader time frame and without the need for prolonged participation. For instance, in 2020, Iowa’s caucus system faced criticism for its complexity and inaccessibility, while states like New Hampshire, which uses a primary system, saw higher voter turnout.

The strategic implications of caucuses and primaries also differ. Caucuses often amplify the influence of grassroots organizers and passionate activists, as their ability to persuade others during the event can sway outcomes. Primaries, however, tend to reflect broader public opinion, as they are less susceptible to small, vocal groups dominating the process. Candidates must tailor their campaigns accordingly: in caucus states, they focus on mobilizing dedicated supporters, while in primary states, they emphasize broad appeal and media presence. This distinction highlights how the choice between caucus and primary can shape the trajectory of a candidate’s campaign.

Practical considerations further underscore the differences. Caucuses require significant organizational effort and volunteer involvement, making them resource-intensive for both parties and participants. Primaries, managed by state election officials, are generally more streamlined and cost-effective. For voters, understanding these systems is crucial. In caucus states, arriving early and being prepared to stay for the duration is essential, while in primary states, knowing polling locations and hours is key. Both systems, however, serve the same ultimate purpose: to give voters a voice in selecting their party’s presidential nominee.

In conclusion, the choice between caucus and primary systems reflects deeper philosophical differences in how states approach democracy. Caucuses prioritize engagement and deliberation, fostering a sense of community but at the cost of accessibility. Primaries emphasize efficiency and inclusivity, making participation easier but potentially diluting the intensity of voter involvement. As states continue to debate the merits of each system, voters must navigate these differences to effectively participate in the nomination process. Understanding these distinctions empowers citizens to engage more meaningfully in one of the most critical aspects of American politics.

Rescheduling Interviews Gracefully: A Guide to Professional Communication

You may want to see also

Caucus Process: Steps involved, including voter gatherings, alignment, and delegate selection

Caucuses are a distinctive method of political participation, offering a more interactive and communal approach to candidate selection compared to primary elections. The caucus process is a multi-step journey, beginning with local gatherings that foster direct engagement among voters. These meetings are not merely about casting ballots; they are forums for debate, persuasion, and collective decision-making. This hands-on approach allows participants to actively advocate for their preferred candidates, making caucuses a vibrant, if sometimes chaotic, democratic exercise.

The first step in the caucus process is the voter gathering, typically held in schools, community centers, or even private homes. Unlike the private act of voting in a primary, caucus attendees assemble in public spaces, often divided into groups based on their candidate preferences. This phase is crucial for undecided voters, as it provides an opportunity to hear arguments from fellow citizens and potentially shift allegiances. For instance, in Iowa’s caucuses, participants physically move to designated areas of the room to show their support, a process known as "aligning." This visible demonstration of preference adds a layer of transparency and social pressure, encouraging attendees to make informed choices.

Alignment is the heart of the caucus process, where the art of persuasion takes center stage. After the initial grouping, supporters of candidates who fail to meet a viability threshold (usually 15% of attendees) must either join another candidate’s group, remain uncommitted, or attempt to recruit others to their cause. This phase can be both strategic and intense, as individuals negotiate and debate to sway others to their side. For example, a passionate advocate for a lesser-known candidate might highlight policy positions or personal qualities to attract undecided voters. This dynamic interaction contrasts sharply with the solitary act of voting in a primary, emphasizing community involvement and direct democracy.

The final step in the caucus process is delegate selection, which translates local preferences into broader party representation. Each group’s size determines the number of delegates it can send to the county, state, or national convention. These delegates are typically committed to supporting their assigned candidate at subsequent levels of the process. However, the delegate selection process can be complex, involving mathematical calculations and sometimes even coin tosses to resolve ties. This step underscores the caucus system’s focus on proportional representation, ensuring that minority viewpoints within the party are not entirely overlooked.

While caucuses foster deeper engagement and community interaction, they are not without challenges. The time-consuming nature of gatherings, often lasting hours, can deter participation, particularly among working individuals or those with caregiving responsibilities. Additionally, the public nature of alignment may discourage voters who prefer privacy. Despite these drawbacks, caucuses remain a vital mechanism for grassroots democracy, offering a unique space for voters to actively shape their party’s direction. For those willing to invest the time, the caucus process provides an unparalleled opportunity to influence political outcomes through dialogue, persuasion, and collective action.

Brain Drain's Impact: How Talent Migration Shapes Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Historical Origins: Roots of caucuses in early American political party organization

The roots of caucuses in early American political party organization trace back to the late 18th century, when the nation’s fledgling democracy sought structured ways to nominate candidates and shape party platforms. Emerging as informal gatherings of like-minded politicians, caucuses were the original incubators of party strategy, operating behind closed doors to select candidates for public office. These early meetings, often held by congressional delegations or state party leaders, were shrouded in secrecy, reflecting the era’s elitist political culture. For instance, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson, relied heavily on caucuses to counterbalance the Federalists’ influence, demonstrating their role as both tactical and ideological tools.

Analyzing their function reveals a stark contrast to modern primaries. Early caucuses were not public events but exclusive forums for party insiders. This exclusivity sparked criticism, with detractors labeling them “king caucuses” for their undemocratic nature. By the 1820s, reformers began pushing for more inclusive nomination processes, culminating in the rise of party conventions. Yet, caucuses persisted, evolving from their secretive origins into more participatory formats. This transformation underscores their adaptability, a trait that has allowed them to remain relevant in certain states’ political landscapes.

To understand their enduring legacy, consider the practical mechanics of early caucuses. Participants would gather in a designated location, often a private room or legislative chamber, to debate and vote on candidates. Unlike modern primaries, which rely on secret ballots, caucus attendees publicly declared their preferences, fostering intense deliberation. This method, while open to coercion or influence, encouraged direct engagement and compromise—a hallmark of early American political culture. For historians and political scientists, studying these procedures offers insights into the nation’s democratic evolution.

Comparatively, the shift from caucuses to primaries reflects broader societal changes. As suffrage expanded and political power decentralized, the demand for more transparent, accessible nomination processes grew. Yet, states like Iowa and Nevada retain caucuses, preserving a direct link to this historical tradition. Their continued use highlights the tension between tradition and progress, a recurring theme in American politics. For modern voters, understanding this history provides context for why caucuses remain a contentious yet enduring feature of the electoral process.

In conclusion, the historical origins of caucuses reveal their dual nature as both a product of early American political pragmatism and a symbol of its limitations. From their secretive beginnings to their current, more public forms, caucuses have mirrored the nation’s evolving democratic ideals. By examining their roots, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for their role in party organization but also a critical lens through which to evaluate their place in contemporary politics. This historical perspective is essential for anyone seeking to understand—or reform—the mechanisms of American democracy.

Assessing Political Commitment: Strategies to Measure and Evaluate Willpower

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$16.19 $17.99

$28.6 $36.99

Pros and Cons: Advantages (engagement) and disadvantages (low turnout, complexity) of caucuses

Caucuses, as a method of political participation, offer a unique blend of grassroots engagement and procedural complexity. Unlike primary elections, where voters cast ballots privately and quickly, caucuses require attendees to gather in person, discuss candidates, and publicly declare their support. This format fosters a sense of community and deepens political engagement by encouraging dialogue and persuasion. For instance, in Iowa’s Democratic caucuses, participants physically move to designated areas within a room to align with their preferred candidate, a process that demands active involvement and commitment. This hands-on approach can strengthen party unity and educate participants about the political process, making it a powerful tool for civic engagement.

However, the very nature of caucuses that promotes engagement also contributes to their most significant drawback: low turnout. The time-consuming and often inconvenient process—typically held on a single evening and lasting hours—excludes many potential participants. Working parents, shift workers, and individuals with disabilities may find it impossible to attend, effectively silencing their voices. For example, during the 2020 Iowa caucuses, the Democratic Party’s complex reporting system led to delays and confusion, further discouraging participation. This exclusivity undermines the democratic principle of equal representation, as only the most dedicated or privileged voters are able to participate.

Another critical disadvantage of caucuses is their complexity, which can alienate even well-intentioned participants. The rules vary by party and state, often requiring attendees to navigate intricate procedures like viability thresholds (e.g., a candidate must receive at least 15% support in a precinct to earn delegates). This complexity not only deters first-time participants but also opens the door to procedural errors and disputes. In 2016, Nevada’s Democratic caucuses faced criticism for chaotic organization and unclear rules, leaving many attendees frustrated and disengaged. Such barriers can erode trust in the political process, defeating the purpose of fostering civic participation.

Despite these challenges, caucuses retain a distinct advantage in their ability to amplify grassroots activism. The public nature of the process allows passionate supporters to advocate for their candidates, potentially swaying undecided attendees. This dynamic can elevate lesser-known candidates who might otherwise struggle in a traditional primary system. For example, Barack Obama’s 2008 caucus victories in states like Iowa were fueled by organized grassroots campaigns, demonstrating the power of this format to reward ground-level mobilization. This aspect makes caucuses particularly appealing to parties seeking to build a robust, engaged base.

In weighing the pros and cons, it’s clear that caucuses are a double-edged sword. While they excel at fostering deep engagement and grassroots energy, their logistical demands and complexity limit accessibility and turnout. To maximize their benefits, states and parties could consider hybrid models, such as introducing early caucus options or simplifying rules to reduce barriers. Ultimately, the value of caucuses lies in their ability to balance inclusivity with the intensity of participation—a challenge that requires thoughtful reform to ensure they serve all voters equitably.

Understanding Political Office: Roles, Responsibilities, and Public Service Explained

You may want to see also

Notable Examples: Iowa caucuses and their influence on presidential election campaigns

The Iowa caucuses, held every four years, are often the first major test for presidential candidates in the United States. Unlike primary elections, which use secret ballots, caucuses are local gatherings where voters publicly declare their support for a candidate through a series of alignments and discussions. This process, unique to Iowa, amplifies the influence of grassroots organizing and retail politics, as candidates must engage directly with voters in small towns and rural areas. The Iowa caucuses are not just a contest of popularity but a measure of a campaign’s ground game, making them a critical early indicator of a candidate’s viability.

Consider the 2008 Iowa caucuses, where Barack Obama’s victory over Hillary Clinton and John Edwards reshaped the Democratic primary narrative. Obama’s win was fueled by a coalition of young voters, African Americans, and independents, demonstrating the power of mobilizing underrepresented demographics. This victory not only propelled Obama toward the nomination but also established Iowa as a launching pad for candidates who can inspire and organize diverse groups. Conversely, Clinton’s third-place finish exposed vulnerabilities in her campaign, underscoring the high-stakes nature of performing well in Iowa.

While Iowa’s influence is undeniable, it is not without criticism. The state’s predominantly white and rural population has sparked debates about its representativeness of the broader electorate. For instance, in 2016, Bernie Sanders narrowly lost to Hillary Clinton in Iowa, despite strong support from younger voters. This outcome highlighted the challenges of translating enthusiasm into caucus victories, as the process favors candidates with organized, committed supporters who can navigate the time-consuming caucus system. Campaigns must therefore balance national appeal with the specific demands of Iowa’s electorate.

Practical tips for candidates aiming to succeed in Iowa include starting early, investing in local organizers, and tailoring messages to resonate with rural and agricultural concerns. For voters, understanding the caucus rules—such as the 15% viability threshold and realignment process—is crucial for effectively participating. Despite its limitations, Iowa remains a proving ground for candidates, offering a unique opportunity to demonstrate organizational strength and connect with voters on a personal level. Its influence persists not just as a predictor of success but as a cultural phenomenon that sets the tone for the entire presidential campaign.

Witnesses and Politics: Exploring Beliefs, Engagement, and Neutrality in Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Caucuses are private meetings of political party members within a state or district to select their preferred candidate for an upcoming election, often through discussion and voting.

Caucuses involve in-person gatherings where participants openly discuss and vote for their candidate, while primaries are state-run elections where voters cast secret ballots at polling places.

A handful of states, such as Iowa, Nevada, and Wyoming, traditionally use caucuses as part of their presidential nomination process, though some have shifted to primaries in recent years.

Caucuses are criticized for their low turnout, time-consuming nature, and lack of accessibility, as they often require participants to spend hours at a specific location, excluding those with work or family commitments.