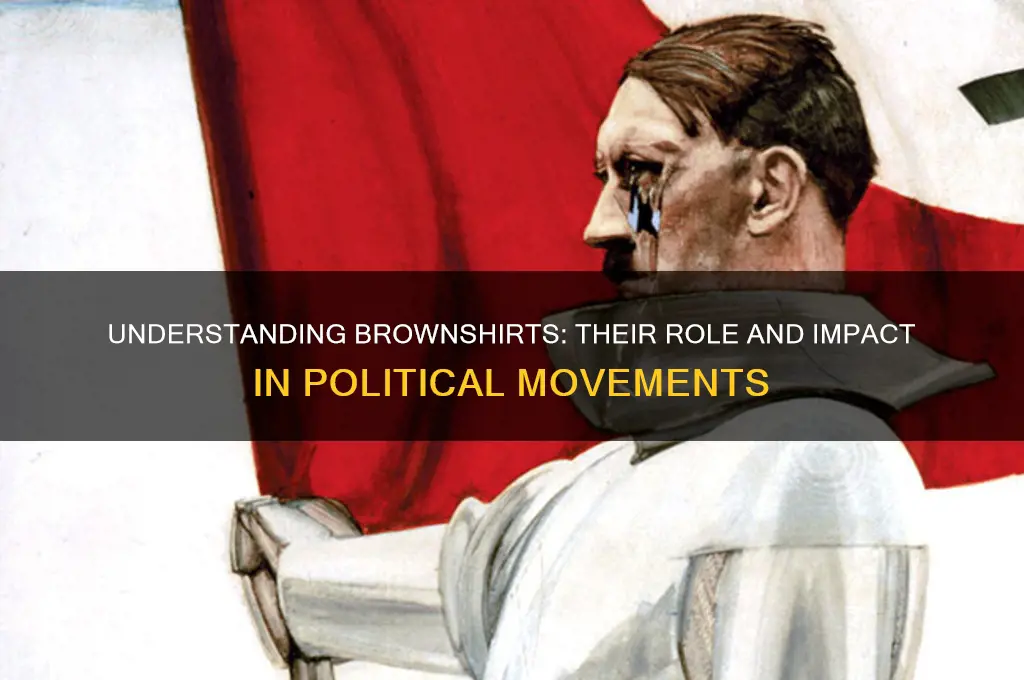

Brownshirts, historically associated with the Nazi Party in Germany, were members of the Sturmabteilung (SA), a paramilitary organization known for their brown uniforms and violent tactics. In the political context, the term brownshirts has come to symbolize extremist groups or individuals who use intimidation, violence, or authoritarian methods to advance their political agendas. Often linked to far-right ideologies, these groups may employ street violence, harassment, or suppression of dissent to achieve their goals. The term is sometimes used metaphorically in contemporary political discourse to describe organizations or movements perceived as threatening democratic norms or engaging in aggressive, militant behavior. Understanding the historical and modern implications of brownshirts is crucial for analyzing the rise of authoritarian tendencies and the erosion of civil liberties in politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin | The term "Brownshirts" originates from the Nazi Party's paramilitary wing, the Sturmabteilung (SA), known for their brown uniforms. |

| Ideology | Associated with far-right, authoritarian, and fascist ideologies, often promoting nationalism, racism, and xenophobia. |

| Role | Historically, Brownshirts were used to intimidate political opponents, disrupt meetings, and enforce party agendas through violence. |

| Modern Usage | In contemporary politics, the term is often used metaphorically to describe extremist groups or individuals who use intimidation and violence to advance political goals. |

| Tactics | Street violence, harassment, propaganda, and the suppression of dissent are common tactics. |

| Symbolism | Brown shirts or uniforms, flags, and insignia are used as symbols of authority and unity among members. |

| Leadership | Typically led by charismatic figures who promote a cult of personality and absolute loyalty. |

| Opposition | Targets often include minority groups, political opponents, journalists, and anyone perceived as a threat to their ideology. |

| Historical Context | Most famously associated with Nazi Germany, but similar groups have existed in other fascist regimes and modern extremist movements. |

| Legal Status | Often operate in legal gray areas, sometimes tolerated or even supported by sympathetic governments, but can also be outlawed. |

| Global Presence | Similar groups exist worldwide, though they may not explicitly identify as "Brownshirts," they share comparable characteristics and goals. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origins of the Brownshirts

The Brownshirts, officially known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), emerged in the early 1920s as a paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. Their origins are deeply rooted in the turbulent political landscape of post-World War I Germany, where economic instability, social unrest, and widespread disillusionment created fertile ground for extremist ideologies. Founded by Ernst Röhm in 1921, the SA initially served as a protective force for Nazi Party meetings, often clashing with rival political groups, particularly communists and socialists. Their early role was pragmatic: to intimidate opponents and assert Nazi dominance in the streets.

The SA’s rapid growth was fueled by its ability to attract disaffected veterans, unemployed workers, and young men seeking purpose in a chaotic era. By 1923, the Brownshirts numbered in the tens of thousands, becoming a visible symbol of Nazi aggression. Their uniform—brown shirts, swastika armbands, and military-style caps—was both practical and symbolic, designed to project unity and strength. However, their origins were not without internal tensions. The SA’s leadership, including Röhm, often clashed with Adolf Hitler over the organization’s role, with Röhm advocating for a more revolutionary approach while Hitler prioritized political consolidation.

A critical turning point in the SA’s origins was its role in the failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, where Hitler and the Brownshirts attempted to seize power in Munich. The coup’s failure led to Hitler’s imprisonment and a temporary ban on the Nazi Party, but it also cemented the SA’s reputation as a radical, violent force. During the mid-1920s, when the Nazi Party was legally restricted, the SA operated semi-clandestinely, maintaining its structure and preparing for a resurgence. This period of relative obscurity was crucial, as it allowed the Brownshirts to refine their tactics and deepen their ties to local communities.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, the SA became a central tool in the Nazi Party’s rise to power. Their street battles with political opponents, particularly during the Great Depression, helped create an atmosphere of fear and instability that Hitler exploited to gain support. However, their origins as a semi-autonomous, often unruly force would later lead to their downfall. In 1934, during the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler purged the SA leadership, including Röhm, to consolidate his control and appease the German military. This marked the end of the SA’s political influence, though they remained a symbolic presence until the end of the Nazi regime.

Understanding the origins of the Brownshirts offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked paramilitary groups in politics. Their rise from a protective force to a tool of terror underscores how extremist ideologies can exploit societal vulnerabilities. For modern observers, the SA’s history serves as a reminder to vigilantly monitor the emergence of similar groups, particularly in times of economic or political crisis. Practical steps include supporting democratic institutions, fostering civic education, and addressing root causes of discontent before they escalate into violence.

Is Jim Florentine Political? Exploring His Views and Stances

You may want to see also

Role in Nazi Germany

The brownshirts, officially known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), were the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and their role in Nazi Germany was both foundational and transformative. Initially formed in the early 1920s as a protective squad for Nazi leaders, the SA quickly evolved into a formidable force for street-level intimidation and political violence. Their primary function was to disrupt meetings of opposing political parties, particularly the Communists and Social Democrats, through brute force. This tactic, known as *Saalschlachten* (hall battles), cemented their reputation as the muscle behind Hitler’s rise to power. By the late 1920s, the SA had grown into a nationwide organization, boasting over 400,000 members by 1932, making them a critical tool in the Nazi Party’s strategy to destabilize the Weimar Republic.

However, the SA’s role was not merely one of physical intimidation; they also served as a populist bridge between the Nazi Party and the working class. Led by Ernst Röhm, the SA attracted disaffected veterans, unemployed youth, and those disillusioned with the economic and political status quo. Their brown uniforms, a symbol of unity and strength, became a familiar sight in German cities, fostering a sense of fear among opponents and loyalty among followers. This dual role—as enforcers and recruiters—made the SA indispensable during the Nazis’ early years, helping to mobilize mass support and create an aura of inevitability around Hitler’s leadership.

Despite their pivotal role in the Nazi ascent, the SA’s influence began to wane after Hitler became Chancellor in 1933. The organization’s radical, revolutionary ethos clashed with the conservative elements of German society, including the military and industrial elites, whom Hitler sought to appease. Röhm’s vision of a socialist revolution and his desire to merge the SA with the army threatened Hitler’s consolidation of power. This tension culminated in the *Night of the Long Knives* in June 1934, when Hitler, with the aid of the SS, purged the SA leadership, executing Röhm and other high-ranking members. This brutal act not only eliminated a potential rival but also signaled the SA’s demotion from a central role in Nazi politics to a ceremonial one.

In the years following the purge, the SA’s functions were largely absorbed by other Nazi organizations, particularly the SS, which emerged as the regime’s primary instrument of terror and control. The SA continued to exist, but its role was reduced to propaganda activities, such as organizing rallies and parades, and maintaining order within the party. By the outbreak of World War II, the SA had become a shadow of its former self, its members often relegated to auxiliary roles in the war effort. Yet, their early contributions to the Nazi regime’s rise remain a stark reminder of how paramilitary groups can exploit political instability to reshape a nation’s trajectory.

In retrospect, the SA’s role in Nazi Germany illustrates the dangers of unchecked paramilitary organizations in politics. Their ability to mobilize violence and sway public opinion was instrumental in dismantling democratic institutions and paving the way for totalitarian rule. While their influence diminished after 1934, the legacy of the brownshirts endures as a cautionary tale about the fragility of democracy in the face of organized aggression. Understanding their rise and fall offers critical insights into the mechanisms of authoritarianism and the importance of safeguarding democratic norms against such threats.

Exploring the Truth Behind Canada's Reputation for Politeness

You may want to see also

Tactics and Violence

The Brownshirts, formally known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), were the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and their tactics and violence were central to their political strategy. Unlike conventional political organizations that relied on debate and persuasion, the SA employed intimidation, disruption, and brute force to advance their agenda. Their primary tactic was to create an atmosphere of fear and chaos, targeting political opponents, Jews, and anyone deemed a threat to the Nazi regime. Street brawls, beatings, and public humiliation were common tools in their arsenal, designed to suppress dissent and assert dominance. This approach was not merely reactive but calculated, aiming to destabilize the Weimar Republic and pave the way for Hitler’s rise to power.

One of the most effective tactics of the Brownshirts was their use of mass mobilization and public spectacle. They organized large-scale rallies, marches, and demonstrations, often accompanied by violence, to showcase their strength and intimidate opponents. These events were carefully choreographed to create an illusion of overwhelming support for the Nazi cause. For instance, during the early 1930s, the SA would disrupt meetings of rival political parties, breaking up gatherings and attacking attendees. This not only silenced opposition but also signaled to the public that resistance was futile. The psychological impact of such tactics cannot be overstated; they fostered a sense of inevitability around Nazi dominance, discouraging resistance and encouraging compliance.

Violence was not just a means to an end for the Brownshirts but also a tool for internal discipline and cohesion. The SA’s ranks were often filled with young, disaffected men who found purpose and camaraderie in the group’s aggressive culture. Training exercises, which included combat drills and ideological indoctrination, reinforced loyalty to the Nazi cause. However, this internal violence also led to power struggles within the party, culminating in the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, when Hitler purged the SA leadership to consolidate his control. This event highlights the double-edged nature of the Brownshirts’ tactics: while their violence was instrumental in securing power, it also posed a threat to the regime’s stability once its usefulness had diminished.

A comparative analysis reveals that the Brownshirts’ tactics were not entirely unique but were employed with unprecedented scale and ruthlessness. Similar paramilitary groups existed in other fascist movements, such as Mussolini’s Blackshirts in Italy, but the SA’s integration of violence into everyday politics was particularly systematic. Their success lay in their ability to blur the lines between political activism and criminality, exploiting legal loopholes and public apathy to operate with impunity. For modern observers, this serves as a cautionary tale: the normalization of political violence can undermine democratic institutions and pave the way for authoritarianism.

In practical terms, understanding the tactics of the Brownshirts offers lessons for countering extremist groups today. Key strategies include early intervention to disrupt recruitment efforts, legal measures to hold perpetrators accountable, and public education to build resilience against intimidation. For instance, monitoring online platforms where extremist groups organize can prevent the spread of their ideology and coordination of violent actions. Additionally, fostering inclusive political environments that address the root causes of disaffection can reduce the appeal of such groups. While history does not repeat itself exactly, the playbook of the Brownshirts remains a stark reminder of how violence can be weaponized in the pursuit of power.

Mastering Political Debates: Strategies for Constructive and Respectful Arguments

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Leadership and Structure

The Brownshirts, formally known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), were the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and their leadership and structure played a pivotal role in the rise of Adolf Hitler and the consolidation of Nazi power. At the helm was Ernst Röhm, a ruthless organizer who transformed the SA into a formidable force of street fighters and enforcers. Röhm’s leadership was characterized by his ability to mobilize and radicalize members, often through direct action and violence against political opponents. However, his autonomy and ambition eventually led to his downfall during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, as Hitler sought to centralize control. This event underscores a critical aspect of Brownshirt leadership: it was inherently hierarchical, with loyalty to Hitler as the ultimate authority, but also prone to internal power struggles.

Structurally, the SA was organized along military lines, with regional and local units commanded by officers who reported up a chain of command. This militarized structure allowed for rapid mobilization and coordination, making the Brownshirts effective in disrupting political rallies, intimidating voters, and enforcing Nazi ideology. However, this same structure also created inefficiencies and rivalries, particularly between the SA and other Nazi organizations like the SS. The SA’s decentralized nature, while useful for grassroots mobilization, often led to conflicts over jurisdiction and authority. For instance, local SA leaders frequently acted with impunity, undermining the party’s broader strategic goals. This duality—centralized loyalty to Hitler but decentralized operational control—was both a strength and a weakness.

A key takeaway from the Brownshirt leadership model is the importance of balancing centralized authority with operational flexibility. Leaders must maintain ultimate control to ensure alignment with overarching goals, but they must also empower local units to act decisively. Modern political movements can learn from this by establishing clear chains of command while allowing for localized adaptation. For example, a national campaign might set overarching messaging guidelines but permit regional teams to tailor strategies to local demographics. However, caution must be exercised to prevent the rise of rogue leaders who could threaten the movement’s cohesion, as seen with Röhm.

Comparatively, the Brownshirts’ structure contrasts sharply with that of more decentralized movements, such as modern grassroots activism. While the SA’s militarized hierarchy enabled rapid and forceful action, it stifled creativity and dissent. In contrast, decentralized movements often thrive on diversity of thought and flexible leadership, though they may struggle with coordination. Political organizers today face the challenge of determining whether their goals require the discipline of a hierarchical structure or the adaptability of a decentralized one. The Brownshirts’ example suggests that the choice depends on the nature of the objectives: hierarchical structures are better suited for seizing and consolidating power, while decentralized models excel at fostering innovation and resilience.

In practical terms, anyone studying or implementing leadership structures should consider the following steps: first, define the core objectives and determine whether a centralized or decentralized approach aligns better with those goals. Second, establish clear lines of authority while allowing for local autonomy where necessary. Third, monitor for signs of internal power struggles and address them proactively to maintain unity. Finally, regularly evaluate the structure’s effectiveness and be prepared to adapt as circumstances change. The Brownshirts’ rise and fall offer a stark reminder that leadership and structure are not static but must evolve to meet the demands of the political landscape.

Unveiling the Devastating Consequences of Political Corruption: A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Historical Legacy and Impact

The term "brownshirts" evokes a chilling historical legacy, rooted in the rise of Nazi Germany's Sturmabteilung (SA), a paramilitary organization known for its violent tactics and role in consolidating Adolf Hitler's power. Their brown uniform shirts became a symbol of intimidation, political thuggery, and the suppression of dissent. This legacy extends far beyond the 1930s, serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked extremism and the erosion of democratic norms.

Analyzing the impact of the brownshirts reveals a blueprint for authoritarian movements. Their tactics included street violence, intimidation of political opponents, and the disruption of public gatherings. This strategy, often referred to as "stochastic terrorism," aimed to create an atmosphere of fear and instability, paving the way for a strongman leader to present themselves as the solution. The SA's role in the Nazi rise to power demonstrates how paramilitary groups can be weaponized to undermine democratic institutions and silence opposition.

The brownshirt legacy also highlights the importance of recognizing and countering early warning signs of authoritarianism. Look for the normalization of political violence, the dehumanization of opponents, and the erosion of independent media. History shows that ignoring these signs can have catastrophic consequences. Vigilance, education, and a commitment to democratic principles are essential antidotes to the brownshirt phenomenon.

Modern examples of groups echoing brownshirt tactics exist, though often under different guises. From white supremacist militias to extremist political factions, the playbook remains disturbingly familiar: intimidation, violence, and the exploitation of societal divisions. Understanding the historical legacy of the brownshirts equips us to identify and challenge these dangerous trends before they escalate into full-blown authoritarianism. It's a reminder that democracy requires constant vigilance and active defense.

Was Palestinian Identity Politically Crafted? Unraveling Historical and Cultural Narratives

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Brownshirts refer to the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party in Germany, officially known as the Sturmabteilung (SA). They were known for their brown uniforms and played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power, using intimidation and violence against political opponents.

The Brownshirts were initially used to protect Nazi meetings and disrupt those of opposing parties. Later, they became a tool for terrorizing political enemies, Jews, and other minorities, helping to consolidate Nazi control through fear and violence.

The original Brownshirts ceased to exist after the Nazi regime fell in 1945. However, the term is sometimes used metaphorically to describe extremist or paramilitary groups that use violence to advance political agendas, often associated with far-right ideologies.