Artificial political boundaries are human-made divisions that separate territories, often established through treaties, agreements, or historical events, rather than natural geographic features like rivers or mountain ranges. These boundaries are created to define the limits of political entities such as countries, states, or provinces, and they play a crucial role in shaping international relations, governance, and cultural identities. Unlike natural boundaries, which are often more fluid and less contentious, artificial boundaries can lead to disputes, conflicts, and challenges related to resource allocation, ethnic tensions, and sovereignty. Understanding the origins, implications, and impacts of these boundaries is essential for addressing geopolitical issues and fostering cooperation in an increasingly interconnected world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Artificial political boundaries are borders created by humans, often through agreements, treaties, or external imposition, rather than natural features like rivers or mountains. |

| Purpose | To delineate political entities (e.g., countries, states) for administrative, economic, or strategic purposes. |

| Creation Process | Often established through negotiations, colonial decrees, or post-conflict settlements. |

| Examples | The Durand Line (Afghanistan-Pakistan), the 49th Parallel (USA-Canada), and the borders of many African countries post-colonialism. |

| Lack of Natural Basis | Unlike natural boundaries (e.g., rivers, mountains), these are arbitrary and not tied to geographical features. |

| Impact on Identity | Can create divisions among culturally or ethnically similar groups, leading to tensions or conflicts. |

| Flexibility | Subject to change through treaties, wars, or political agreements (e.g., the reunification of Germany). |

| Economic Implications | May hinder or facilitate trade, migration, and resource sharing depending on political relations. |

| Historical Context | Often rooted in colonial history, Cold War geopolitics, or post-imperial power dynamics. |

| Modern Relevance | Continues to shape international relations, migration patterns, and regional conflicts (e.g., Israel-Palestine border disputes). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical creation of borders based on colonial powers' interests, not cultural or ethnic lines

- Impact of arbitrary boundaries on ethnic groups, causing division and conflict within communities

- Economic effects of artificial borders on trade, resource distribution, and regional development disparities

- Political instability due to forced boundary demarcations and contested territorial claims between nations

- Role of international treaties and organizations in maintaining or redefining artificial political boundaries

Historical creation of borders based on colonial powers' interests, not cultural or ethnic lines

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 exemplifies how colonial powers carved up Africa with little regard for existing cultural or ethnic boundaries. European nations, driven by imperial ambition and economic exploitation, drew straight lines on maps to divide territories. These lines often bisected communities, separated tribes, and created artificial states. For instance, the border between Nigeria and Cameroon cuts through the territory of the Fulani people, a historically unified ethnic group. This disregard for indigenous identities sowed the seeds of future conflicts and governance challenges.

Consider the Middle East, where the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 between Britain and France partitioned the Ottoman Empire into spheres of influence. The resulting borders, such as those between Iraq, Syria, and Jordan, were drawn to serve colonial interests rather than reflect the region’s diverse ethnic and religious groups. The inclusion of Kurds, Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs, and other minorities within these arbitrary boundaries has led to decades of instability and separatist movements. This case highlights how colonial-era borders prioritized control over cohesion, creating fragile states prone to internal strife.

To understand the long-term consequences, examine the Indian subcontinent. The 1947 partition of India and Pakistan, overseen by British colonial authorities, was based on religious lines but executed with haste and indifference to local realities. The Radcliffe Line, which divided the region, split communities, families, and even irrigation systems, leading to mass migrations and violence. This artificial division, driven by the British desire for a swift exit, ignored centuries-old cultural and economic ties, leaving a legacy of tension and conflict between the two nations.

A comparative analysis reveals that colonial borders often fail to align with the natural contours of societies. In contrast, borders shaped by indigenous agreements or gradual cultural integration tend to be more stable. For example, the borders of pre-colonial African kingdoms, such as the Ashanti Empire, were fluid and based on alliances and trade networks. When colonial powers imposed rigid boundaries, they disrupted these systems, creating states that struggle to foster national unity. This contrast underscores the importance of considering cultural and ethnic realities in border-making.

Practical steps to address the legacy of artificial borders include fostering cross-border cooperation and cultural exchanges. For instance, the European Union’s Schengen Area demonstrates how removing barriers can promote unity despite historical divisions. In Africa, initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area aim to transcend colonial borders by encouraging economic integration. Policymakers must also prioritize inclusive governance models that recognize and empower minority groups within these artificially created states. By learning from history, we can mitigate the adverse effects of borders drawn without regard for human geography.

Is 'Jipped' Politically Incorrect? Unpacking Language Sensitivity and Respect

You may want to see also

Impact of arbitrary boundaries on ethnic groups, causing division and conflict within communities

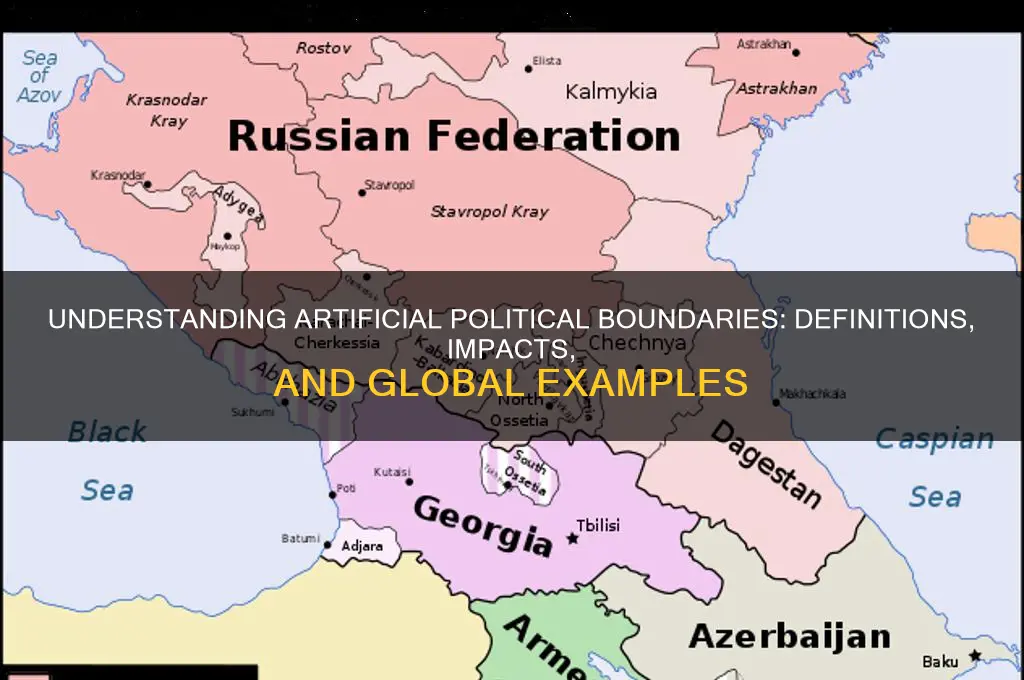

Artificial political boundaries, often drawn without regard for cultural or ethnic cohesion, have historically fragmented communities, sowing seeds of division and conflict. Consider the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, which carved up the Middle East into modern states like Iraq and Syria, lumping together disparate ethnic and religious groups under single governments. This arbitrary division ignored centuries-old tribal and sectarian identities, creating fertile ground for tensions that persist today. The Kurds, for instance, were split among Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran, leading to decades of statelessness and conflict as they fought for autonomy. This example underscores how boundaries imposed without cultural sensitivity can fracture communities, fostering resentment and instability.

To understand the impact, examine the psychological and social consequences of such divisions. When ethnic groups are forcibly separated by political borders, their shared identity and traditions are often suppressed or politicized. In Rwanda, the colonial-era distinction between Hutus and Tutsis, reinforced by Belgian administrators, exacerbated existing social hierarchies. This artificial divide culminated in the 1994 genocide, where ethnic identity became a tool for violence. Similarly, in Myanmar, the Rohingya, an ethnic minority, have faced systemic persecution due to their exclusion from the national identity defined by arbitrary state boundaries. These cases illustrate how political lines can weaponize ethnicity, turning neighbors into adversaries.

Addressing these issues requires a multi-faceted approach. First, recognize the legitimacy of ethnic identities and their right to self-determination. International frameworks like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provide a starting point, but implementation remains inconsistent. Second, invest in cross-border initiatives that foster cultural exchange and economic cooperation. For instance, the European Union’s regional development funds have helped mitigate historical divisions by promoting shared prosperity. Third, revise educational curricula to emphasize shared histories and pluralistic narratives, countering the narratives of division. Practical steps include bilingual education programs and community-led peacebuilding projects.

However, caution is necessary. Redrawing borders is often impractical and can lead to further violence, as seen in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Instead, focus on decentralizing power and granting regional autonomy, as in the case of Spain’s Basque Country or India’s Nagaland. These models allow ethnic groups to preserve their culture and governance within existing state structures. Additionally, avoid romanticizing ethnic homogeneity; diversity, when managed inclusively, can be a strength. The takeaway is clear: arbitrary boundaries are not immutable. By prioritizing dialogue, autonomy, and shared interests, societies can transform lines of division into bridges of cooperation.

Understanding Political Narratives: Shaping Public Opinion and Policy Decisions

You may want to see also

Economic effects of artificial borders on trade, resource distribution, and regional development disparities

Artificial political boundaries, often drawn without regard for natural, cultural, or economic realities, create friction in global trade networks. Tariffs, customs checks, and regulatory discrepancies at these borders increase transaction costs, reducing the volume of cross-border trade by an estimated 30-50% compared to integrated markets. For instance, the India-Pakistan border, a legacy of colonial partition, imposes tariffs averaging 200% on agricultural goods, stifling what could be a $10 billion trade relationship. Similarly, the U.S.-Mexico border, despite NAFTA/USMCA, still sees delays costing $60 billion annually in lost productivity. These barriers fragment supply chains, forcing businesses to reroute goods through less efficient channels or absorb higher costs, ultimately raising prices for consumers.

Resource distribution suffers acutely when artificial borders bisect critical natural assets. The Nile River, shared by 11 countries, exemplifies this: upstream nations like Ethiopia (building the Grand Renaissance Dam) clash with downstream Egypt over water rights, threatening agricultural output for 250 million people. Similarly, the Caspian Sea’s ambiguous legal status (is it a lake or sea?) hinders oil and gas development, leaving an estimated $1 trillion in reserves untapped due to disputes between Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Iran. Such borders create "resource nationalism," where states hoard commodities rather than cooperate, leading to inefficiencies. For example, Congo’s copper belt, split between the DRC and Zambia, operates at 60% capacity due to mismatched infrastructure and regulatory conflicts.

Regional development disparities widen as artificial borders channel investment into politically favored areas while marginalizing others. The EU’s internal cohesion funds, totaling €392 billion (2021-2027), aim to bridge gaps between regions like Bavaria (GDP per capita: €48,000) and Bulgaria (€10,000). Yet, ex-colonial borders in Africa, such as the Cameroon-Nigeria divide, leave northern Cameroon (per capita income: $1,200) lagging behind southern Nigeria ($2,500) due to historical underinvestment. Similarly, the Korean DMZ creates a stark contrast: South Korea’s GDP is 25x North Korea’s, a disparity rooted in border-driven policies. Such inequalities fuel migration pressures, with 33 million Africans migrating internally in 2020, often from border-adjacent regions, straining urban centers.

To mitigate these effects, policymakers must adopt three strategies: harmonize trade rules through regional blocs (e.g., AfCFTA aims to boost intra-African trade by 52% by 2022), establish joint resource management frameworks (like the Mekong River Commission), and redirect infrastructure spending to borderland areas. For instance, the China-Kazakhstan Khorgos Gateway, a $1.5 billion dry port, increased bilateral trade by 40% in 5 years. However, caution is needed: rushed integration can backfire without addressing corruption (e.g., Central America’s Northern Triangle) or cultural tensions (e.g., Kashmir). Ultimately, artificial borders are economic straitjackets—loosening them requires political will, but the payoff is measurable: the World Bank estimates removing all trade barriers could lift 140 million out of extreme poverty.

Exploring Political History: Power, Events, and Societal Shifts Over Time

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99

Political instability due to forced boundary demarcations and contested territorial claims between nations

Artificial political boundaries, often drawn without regard for cultural, ethnic, or historical contexts, have long been a source of tension and conflict between nations. These boundaries, imposed by colonial powers or international agreements, frequently divide communities and create contested territories that fuel political instability. For instance, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 carved up the Middle East into arbitrary states, sowing the seeds for decades of conflict by ignoring the region’s diverse ethnic and religious groups. Such demarcations highlight how external imposition of borders can disrupt local identities and foster resentment, leading to persistent disputes.

Consider the practical steps nations can take to mitigate instability caused by these boundaries. First, engage in bilateral or multilateral negotiations that prioritize local populations’ interests over geopolitical ambitions. Second, establish joint commissions to address territorial claims through dialogue rather than coercion. For example, the International Court of Justice has resolved disputes like the Cameroon–Nigeria border conflict, demonstrating the effectiveness of legal frameworks. Third, invest in cross-border cooperation initiatives, such as shared infrastructure or economic zones, to incentivize peaceful coexistence. Caution, however, must be exercised to avoid token gestures that fail to address underlying grievances.

A comparative analysis reveals that regions with historically contested boundaries, like the India-Pakistan border or the Israel-Palestine conflict, often experience cyclical violence due to unresolved territorial claims. These cases underscore the importance of addressing root causes rather than merely managing symptoms. In contrast, the European Union’s open borders within the Schengen Area illustrate how shared governance and economic integration can reduce tensions over artificial boundaries. This comparison suggests that political instability is not inevitable but a consequence of how boundaries are managed and perceived.

Descriptively, the human cost of forced boundary demarcations is stark. Communities divided by these lines often face restricted movement, loss of traditional lands, and cultural erosion. For instance, the Kurdish people, split across Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran, have endured decades of marginalization and conflict due to borders that deny their national aspirations. Such scenarios emphasize the need for inclusive policies that recognize and protect minority rights within contested territories. Without this, instability will persist as marginalized groups seek self-determination.

Persuasively, it is clear that artificial political boundaries are not merely lines on a map but catalysts for enduring conflict. Nations must move beyond zero-sum approaches to territorial claims and embrace collaborative solutions. By prioritizing diplomacy, legal mechanisms, and local voices, states can transform boundaries from sources of division into bridges for cooperation. The alternative—continued instability and violence—serves no one’s long-term interests. The challenge lies in the political will to act, but the payoff in peace and stability is immeasurable.

Are Political Independents Conservative? Unraveling the Myth and Reality

You may want to see also

Role of international treaties and organizations in maintaining or redefining artificial political boundaries

Artificial political boundaries, often drawn without regard to cultural, linguistic, or geographic realities, are inherently fragile. Their stability or redefinition hinges on the mechanisms established by international treaties and organizations. These entities serve as both guardians and architects, ensuring that boundaries either endure or evolve in ways that minimize conflict and promote cooperation.

Consider the role of treaties in maintaining boundaries. The 1975 Helsinki Accords, for instance, froze post-World War II borders in Europe, legitimizing them through collective recognition. This treaty-based approach provided a legal framework that discouraged unilateral changes, effectively stabilizing artificial boundaries by embedding them in international law. Similarly, the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties emphasizes the principle of *pacta sunt servanda*—agreements must be kept—which reinforces the sanctity of borders agreed upon in treaties. Such instruments act as a deterrent to revisionist claims, ensuring that boundaries, however artificial, remain respected.

However, international organizations often play a more dynamic role in redefining boundaries when they become sources of tension. The United Nations, through its peacekeeping missions and mediation efforts, has facilitated the redrawing of borders in conflict zones. For example, the UN’s involvement in the Eritrea-Ethiopia border dispute led to the establishment of a neutral boundary commission, which redefined the border based on colonial-era treaties. This process, though contentious, demonstrates how organizations can provide a structured mechanism for boundary redefinition, balancing historical claims with contemporary realities.

A critical takeaway is that treaties and organizations are not merely passive observers but active agents in shaping the lifespan of artificial boundaries. Treaties offer stability by codifying agreements, while organizations provide flexibility by offering platforms for negotiation and dispute resolution. For policymakers, the lesson is clear: leveraging these tools requires a dual strategy—strengthening legal frameworks to maintain boundaries and fostering multilateral dialogue to redefine them when necessary. This approach ensures that artificial boundaries serve as instruments of peace rather than catalysts for conflict.

Is Immigration a Political Science Issue? Exploring Policies and Impacts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Artificial political boundaries are borders created by humans, often through agreements, treaties, or decisions, rather than by natural geographic features like rivers or mountains.

Natural boundaries follow physical features like rivers, mountains, or coastlines, while artificial boundaries are imposed by political or administrative decisions, often disregarding natural divisions.

Artificial boundaries are created to define territories, allocate resources, establish administrative control, or resolve conflicts between nations or groups.

Yes, artificial boundaries can lead to conflicts when they divide ethnic, cultural, or linguistic groups, or when they are perceived as unfair or imposed without local consent.

No, some political boundaries are based on natural features, but many, especially in modern times, are artificial and reflect historical, political, or colonial decisions.