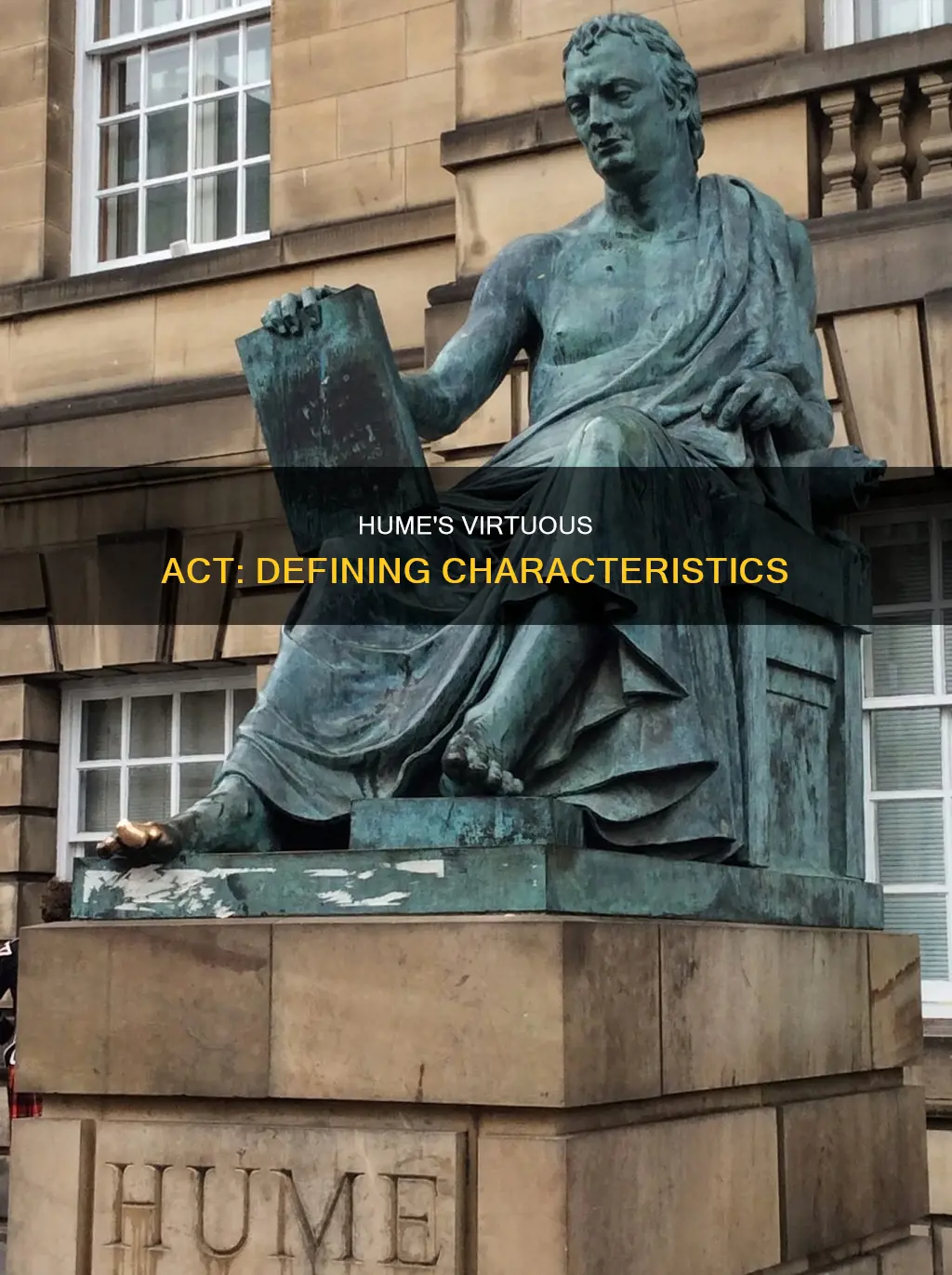

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical skepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. Hume's ethical thought grapples with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, and what it means to live a virtuous life. Hume's moral philosophy revolves around the idea that moral evaluations depend significantly on sentiment or feeling. He rejects the rationalist view that humans make moral judgments solely through reason, arguing that our capacity for sympathy and emotional responsiveness are crucial in determining what is virtuous or vicious. Hume introduces the concept of artificial virtues to explain how we develop a virtuous code beyond what is given by nature, emphasizing the importance of social conventions and justice in shaping our understanding of virtue. According to Hume, moral judgments are based on character traits and motives, and the sentiment of approval or disapproval plays a central role in identifying virtues and vices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Moral evaluations depend on sentiment or feeling | Sympathy, the ability to partake of the feelings, beliefs, and emotions of others |

| Moral evaluations are like aesthetic evaluations | Moral evaluations are a matter of feeling rather than judgment |

| Virtue is not an inherent quality of certain characters or actions | Moral distinctions are not made through a comparison of ideas |

| Moral judgments concern the character traits and motives behind human actions | Moral judgments are made by detecting, through sentiment, the operation of a virtuous or vicious quality of mind |

| Moral judgments are feelings of approval or disapproval | Traits that elicit approval are called "virtues", those that elicit disapproval are called "vices" |

| Moral good and evil are discovered through an emotional responsiveness manifesting itself in approval or disapproval | Moral sense theorists gain awareness of moral good and evil by experiencing the pleasure of approval and the uneasiness of disapproval |

| Moral evaluations require reason to discover the facts of a situation and the general social impact of a trait or practice over time | Reason alone is insufficient to yield a judgment that something is virtuous or vicious |

| Moral worth cannot be attributed to actions done "from duty" | Virtue requires a motive distinct from a sense of its morality |

| Moral worth cannot be attributed to actions done with a motive that refers to the moral goodness of the act | The motive to virtuous action must not itself refer to the moral goodness of the act |

| Moral worth can be attributed to actions done with a motive that is a non-moral, motivating psychological state | Actions deemed virtuous derive their goodness from virtuous motives, motives we approve |

| Moral worth can be attributed to actions done with a motive that is a moral one, a sense of virtue or "regard to the honesty" of the actions | The honest individual repays a loan out of a "regard to justice" |

| Moral worth can be attributed to natural abilities of the mind | Intelligence, good judgment, application, eloquence, and wit are mental qualities that bring individuals the approbation of others |

| Moral worth can be attributed to natural virtues | Natural virtues are virtuous character traits that one could conceivably hold without the need for deterrents and incentives introduced by a civilized society or state |

| Moral worth can be attributed to artificial virtues | Artificial virtues are integral to Hume's thinking as they demonstrate how we can develop our virtuous code beyond what is given to us by nature |

| Moral worth can be attributed to justice | Justice is central to Hume's picture of morality |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hume's anti-rationalism: Moral evaluations are a matter of feeling, not judgment

- Moral sense theory: Moral good and evil are discovered through emotional responsiveness

- Natural virtues: Refers to virtuous character traits that exist without the need for civil society

- Artificial virtues: Virtues developed due to state and social conventions

- Moral worth: Hume rejects Kant's view that a special form of moral worth is attributed to dutiful actions

Hume's anti-rationalism: Moral evaluations are a matter of feeling, not judgment

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical skepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. Hume's ethical thought grapples with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life.

Hume rejects the rationalist conception of morality, whereby humans make moral evaluations and understand right and wrong through reason alone. Instead, he contends that moral evaluations depend significantly on sentiment or feeling. Specifically, it is because we have the requisite emotional capacities, in addition to our faculty of reason, that we can determine that some actions are ethically wrong or that a person has a virtuous moral character.

Hume's anti-rationalist stance is evident in his belief that virtue is not an inherent quality of certain characters or actions. He argues that when we encounter a virtuous character, we feel a pleasurable sensation, but this sensation is not evidence of an inherent quality. If it were, the moral status of a character trait would be inferred from the pleasurable sensation we experience, which would conflict with Hume's anti-rationalism.

Hume clarifies this point by stating that we "do not infer a character to be virtuous, because it pleases: But in feeling that it pleases [we] in effect feel that it is virtuous" (T 3.1.2.3). He believes that moral distinctions are not made through a comparison of ideas but are a matter of feeling rather than judgment (T 3.1.2.1). This feeling is a "`peculiar` kind of sentiment, involving approval (love, pride) or disapproval (hatred, humility) (T 3.3.1.3).

Hume's concept of artificial virtues further illustrates his anti-rationalist position. Artificial virtues are social conventions or systems of cooperation that shape our understanding of virtuous actions. Hume argues that without these social conventions, we would neither have a motive to act virtuously nor approve of virtuous behavior. For example, our approval of acts of kindness does not require a social scheme, but our approval of those who respect property rights does.

In conclusion, Hume's anti-rationalism asserts that moral evaluations are primarily a matter of feeling, not judgment. While reason plays a role in moral judgment, it is our emotional capacities and our ability to sympathize with others that truly enable us to determine what is virtuous or vicious.

The American Constitution: Democracy Examined by Robert Dahl

You may want to see also

Moral sense theory: Moral good and evil are discovered through emotional responsiveness

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical scepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. However, he also made significant contributions to moral philosophy. Hume's ethical thought grapples with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life.

Hume's moral philosophy carves out numerous distinctive philosophical positions. He rejects the rationalist conception of morality, whereby humans make moral evaluations and understand right and wrong through reason alone. Instead, Hume contends that moral evaluations depend significantly on sentiment or feeling. Specifically, it is because we have the requisite emotional capacities, in addition to our faculty of reason, that we can determine that some actions are ethically wrong or that a person has a virtuous moral character.

Hume's view aligns with moral sense theory, which posits that moral good and evil are discovered through emotional responsiveness. According to this theory, we experience the pleasure of approval and the uneasiness of disapproval when contemplating a character trait or action from an imaginatively sensitive and unbiased point of view. Hume argues that while reason is necessary for understanding the facts of a situation and the general social impact of a character trait or practice, it is insufficient for yielding a judgment about its virtuousness or viciousness.

Hume's concept of virtue is not based on inherent qualities or actions. Instead, he believes that virtue is determined by the observer or spectator's emotional response to an action or character trait. When we observe a virtuous act, we feel a pleasurable sensation, which is evidence of our emotional approval. This pleasure is not inferred from the act itself but is a direct response to it.

Hume also distinguishes between natural and artificial virtues. Natural virtues are virtuous character traits that individuals could possess even without the influence of a civilised society or state. These traits are more refined and completed forms of human sentiments that might be found in people who cooperate within small familial groups. Artificial virtues, on the other hand, are shaped by social conventions and systems of cooperation. They are essential for developing a virtuous code that goes beyond what is given by nature, allowing us to become a civil and organised society.

In summary, Hume's moral philosophy emphasises the role of emotional responsiveness in determining moral good and evil. He rejects rationalism, arguing that virtue is not an inherent quality but is instead discovered through our capacity for sympathy and emotional response to the actions and character traits of others.

Personal Freedom and the Constitution

You may want to see also

Natural virtues: Refers to virtuous character traits that exist without the need for civil society

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical skepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. He also made significant contributions to moral philosophy, including the question of what constitutes a virtuous act.

Hume identifies two types of virtues: natural virtues and artificial virtues. Natural virtues refer to virtuous character traits that exist without the need for civil society. They are inherent in human nature and are not dependent on social conventions or systems of cooperation. These virtues are more refined and completed forms of human sentiments that would be expected in people who belonged to no society but cooperated only within small familial groups.

Hume argues that natural virtues are involuntary and are approved because they are either useful to their possessor or immediately agreeable to others. Examples of natural virtues include intelligence, good judgment, application, eloquence, and wit. These mental qualities bring individuals the approbation of others, and their absence is disapproved.

Natural virtues, according to Hume, lead humans towards benevolence and a general code of not obstructing the happiness of others. However, he argues that natural virtues alone are insufficient to constitute a system of values where resources and actions are always deemed fair and equal. This is where artificial virtues come into play.

Artificial virtues, according to Hume, are essential for developing a virtuous code beyond what is given by nature and for creating a civil and organized society. They are the result of state and social conventions and demonstrate how humans can move beyond their inherent selfishness and form a coherent social body.

In summary, Hume's concept of natural virtues refers to virtuous character traits that exist independently of civil society. These traits are inherent in human nature and are refined through cooperation within small groups. They are involuntary and are valued for their usefulness or agreeableness. While natural virtues promote benevolence, they are insufficient on their own to ensure fairness and equality, which is where artificial virtues become necessary.

The Constitution: Godless or God-Given?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Artificial virtues: Virtues developed due to state and social conventions

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical scepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. He also made significant contributions to moral philosophy, grappling with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life.

Hume's moral philosophy introduces the concept of "artificial virtues", which are integral to his thinking on justice and social organisation. Artificial virtues, according to Hume, are virtues that develop due to state and social conventions. They represent a departure from "natural virtues", which are more intrinsic to human nature and can be observed even in small familial groups without the influence of a broader society.

Hume argues that artificial virtues are necessary for us to transcend the limitations of our natural virtues and become a civilised and organised society. Without these artificial virtues, Hume suggests, we would be an inherently selfish race, lacking the cohesion necessary for social harmony.

Artificial virtues, according to Hume, are deeply connected to justice. He contends that natural virtues, while leading us towards benevolence and a general inclination to not impede others' happiness, are insufficient to establish a system of values that ensures fairness and equality in the distribution of resources and actions. This is where artificial virtues come into play, providing the necessary framework for social order and harmony.

Hume's perspective on artificial virtues is tied to his belief that moral evaluations are not solely based on reason, but heavily influenced by sentiment and feeling. He asserts that moral distinctions arise from our capacity for sympathy and our ability to partake in the feelings, beliefs, and emotions of others. This emotional responsiveness results in our approval or disapproval of certain actions and traits, which forms the basis of our moral judgments.

In summary, Hume's concept of artificial virtues highlights the importance of socially constructed virtues that arise from state and social conventions. These artificial virtues are essential for maintaining social order, promoting fairness, and fostering a cohesive and organised society.

The Constitution's Citizenship Clause: Rights and Belonging

You may want to see also

Moral worth: Hume rejects Kant's view that a special form of moral worth is attributed to dutiful actions

David Hume (1711-1776) is known for his philosophical skepticism and empiricist theory of knowledge. He made significant contributions to moral philosophy, grappling with questions about the relationship between morality and reason, the role of human emotion in thought and action, the nature of moral evaluation, human sociability, and what it means to live a virtuous life.

Hume's moral philosophy carves out numerous distinctive philosophical positions. He rejects the rationalist conception of morality, which holds that humans make moral evaluations and understand right from wrong through reason alone. Instead, Hume argues that moral evaluations depend significantly on sentiment or feeling. He believes that it is because we have the requisite emotional capacities, in addition to our faculty of reason, that we can determine whether an action is ethically wrong or whether a person has a virtuous moral character.

Hume's views on the nature of virtue and vice further emphasize the role of sentiment. He claims that virtue is not an inherent quality of certain characters or actions. When we encounter a virtuous character, we feel a pleasurable sensation, but this sensation is not evidence of an inherent quality. Instead, Hume suggests that moral distinctions are made based on feeling rather than judgment. Virtue and vice are not intrinsic to actions or individuals but are determined by the observer or spectator.

Hume's position on the nature of virtue and the role of sentiment in moral evaluation leads him to reject Kant's view of "moral worth." Kant attributes a special form of "moral worth" to actions done "from duty." He argues that a dutiful action, even if praiseworthy, does not express a good will and, therefore, has no genuine "moral worth." According to Kant, the only actions with "moral worth" are those motivated by duty or respect for the moral law itself.

Hume disagrees with this attribution of "moral worth" to dutiful actions. He asserts that "no action can be virtuous, or morally good, unless there be in human nature some motive to produce it, distinct from a sense of its morality." Hume argues that to avoid circularity, the motive for a virtuous action must not refer to the moral goodness of the act itself. In other words, the motive for a virtuous action should not be the sense of its moral goodness.

Hume believes that relying on one's sense of the goodness of an act as a motive is only necessary when one lacks the natural feelings that ordinarily prompt moral behavior, such as natural affection, generosity, or gratitude. He emphasizes that virtue arises from non-moral motives, and our approval of an action is derived from our assessment of the inner motive behind it. This perspective highlights the role of sentiment and human capacity for sympathy in Hume's moral philosophy, contrasting with Kant's emphasis on duty and respect for the moral law.

The Constitution and Habeas Corpus: Can It Be Suspended?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Hume believes that moral evaluations are dependent on sentiment or feeling. He argues that humans require emotional capacities in addition to reason to determine whether an action is ethically wrong or a person has a virtuous character. Hume believes that moral distinctions are a matter of feeling rather than judgment.

Artificial virtues are the bedrock of Hume's view on justice and are integral to his moral philosophy. They are virtues developed purely as a result of the state and social conventions. They are important because they allow us to develop a virtuous code beyond what is given to us by nature, helping us become a society of civil and organised nature.

Natural virtues are virtuous character traits that one could conceivably hold without the need for deterrents and incentives introduced by a civilised society or state. They are more refined and completed forms of human sentiments that we would expect to find in people who cooperate within small familial groups.