A political revolution refers to a profound and transformative change in the structure, power dynamics, and governance of a society, often driven by widespread public discontent and a desire for systemic reform. Unlike a coup or a rebellion, which may focus on replacing individuals or factions in power, a political revolution seeks to fundamentally alter the underlying institutions, ideologies, and principles that govern a nation. It can involve shifts in political systems, such as transitioning from autocracy to democracy, or redefining the relationship between the state and its citizens. Historically, political revolutions, like the French Revolution or the American Revolution, have been catalysts for significant social, economic, and cultural changes, reshaping the course of nations and inspiring movements for justice, equality, and freedom.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Causes of Revolution: Economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation spark revolutionary movements

- Methods of Change: Protests, strikes, civil disobedience, and armed conflict are common tools for political revolution

- Historical Examples: French, Russian, and American revolutions illustrate diverse paths to political transformation

- Outcomes of Revolution: Regime change, new constitutions, and shifts in power dynamics redefine societies post-revolution

- Role of Leadership: Charismatic leaders mobilize masses, shape ideologies, and guide revolutionary processes effectively

Causes of Revolution: Economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation spark revolutionary movements

A political revolution is a fundamental transformation of a state’s political system, often involving a shift in power structures, governance, and ideologies. It is typically driven by widespread dissatisfaction with the existing order, fueled by systemic issues that marginalize large segments of the population. Among the most potent catalysts for such revolutions are economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation. These factors create fertile ground for revolutionary movements by fostering resentment, mobilizing masses, and challenging the legitimacy of ruling authorities. Understanding these causes is essential to grasping why and how political revolutions occur.

Economic inequality stands as a primary driver of revolutionary sentiment. When wealth and resources are concentrated in the hands of a few, while the majority struggles to meet basic needs, it breeds resentment and instability. Historically, stark disparities between the elite and the working class have ignited movements like the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution. In contemporary contexts, globalization and neoliberal policies often exacerbate inequality, leaving many feeling exploited and disenfranchised. Economic grievances, such as poverty, unemployment, and lack of access to opportunities, unite diverse groups under a common cause, making economic inequality a powerful spark for revolutionary change.

Political oppression is another critical factor that fuels revolutionary movements. Authoritarian regimes that suppress dissent, restrict freedoms, and deny basic human rights create environments ripe for rebellion. Examples include the Arab Spring, where decades of authoritarian rule and political repression led to mass uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa. When governments use violence, censorship, or arbitrary power to maintain control, they alienate their citizens and erode trust in institutions. This oppression often radicalizes individuals and groups, pushing them toward revolutionary action as a means to reclaim their rights and dignity.

Social injustice further exacerbates the conditions that lead to revolution. Discrimination based on race, gender, religion, or ethnicity creates systemic barriers that marginalize entire communities. Movements like the American Civil Rights Movement and the global fight against apartheid demonstrate how social injustice can galvanize people to demand equality and justice. When societies fail to address entrenched inequalities and protect the rights of all citizens, the resulting frustration and anger can escalate into revolutionary struggles. Social injustice not only undermines social cohesion but also reinforces the perception that the existing system is inherently unfair and must be overthrown.

Lack of representation in political systems is a final yet equally significant cause of revolution. When governments fail to reflect the interests and needs of their populations, citizens feel alienated and powerless. This was evident in the American Revolution, where colonial grievances against British rule centered on "taxation without representation." In modern times, movements like Occupy Wall Street and protests against corrupt governments highlight the demand for inclusive and accountable governance. Without meaningful representation, people lose faith in the system, making revolutionary change seem like the only viable path to achieving their aspirations.

In conclusion, the causes of revolution—economic inequality, political oppression, social injustice, and lack of representation—are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing. These issues create a sense of injustice and exclusion that drives individuals and communities to challenge the status quo. Political revolutions, therefore, are not spontaneous events but the culmination of long-standing grievances and systemic failures. By addressing these root causes, societies can mitigate the conditions that lead to revolutionary movements and work toward more equitable and just systems. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for both preventing revolutions and fostering sustainable political change.

Will Ferrell's Political Satire: A Hilarious Take on Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Methods of Change: Protests, strikes, civil disobedience, and armed conflict are common tools for political revolution

A political revolution involves fundamental changes in the political power structure, often driven by mass mobilization and collective action. At the heart of such transformations are methods of change that challenge existing systems and demand reform or overhaul. Among the most common tools are protests, strikes, civil disobedience, and armed conflict, each serving distinct purposes and carrying varying levels of risk and impact. These methods are not mutually exclusive and are often used in combination to amplify the revolutionary message and pressure those in power.

Protests are a cornerstone of political revolution, providing a visible and vocal platform for dissent. They range from small, localized gatherings to massive demonstrations involving millions. Protests serve multiple functions: they raise awareness about grievances, demonstrate public support for a cause, and create media attention that can force political leaders to address demands. Effective protests are often well-organized, with clear messaging and nonviolent tactics to maintain public sympathy. However, they can also escalate into confrontations with authorities, particularly when governments respond with repression. Historically, protests have been pivotal in movements like the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and the Arab Spring, where they catalyzed broader societal change.

Strikes are another powerful method, particularly in economic and labor-related revolutions. By withholding their labor, workers can disrupt industries, economies, and even governments, forcing concessions. General strikes, where a substantial portion of the workforce participates, can bring entire cities or countries to a standstill. For example, the 1988 Polish strikes led by the Solidarity movement played a crucial role in dismantling communist rule. Strikes are effective because they target the economic backbone of a regime, making them a high-stakes tool for political change. However, they require significant coordination and solidarity among participants, as strikers often face financial hardship and retaliation.

Civil disobedience involves deliberate, nonviolent refusal to comply with certain laws or commands as a form of political protest. This method, popularized by figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., emphasizes moral appeal and the willingness to accept punishment to highlight injustice. Acts of civil disobedience, such as sit-ins, boycotts, or blocking public spaces, challenge the legitimacy of oppressive laws and systems. They are particularly effective in garnering public and international support, as they often expose the brutality or unfairness of the ruling regime. However, participants must be prepared for arrest and other consequences, making this method both a test of commitment and a powerful symbol of resistance.

Armed conflict represents the most extreme and violent method of political revolution. It involves organized, often militarized resistance against a government or ruling class. Armed conflict arises when other methods fail or when oppression is so severe that violent resistance is seen as the only option. Revolutions like the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Cuban Revolution of 1959 were achieved through armed struggle. However, this method carries immense risks, including loss of life, destruction of infrastructure, and the potential for prolonged instability. Armed conflict also raises ethical questions about the use of violence and its long-term consequences for society.

In conclusion, the methods of change in political revolutions—protests, strikes, civil disobedience, and armed conflict—each play unique roles in challenging and transforming political systems. The choice of method depends on the context, the goals of the movement, and the willingness of participants to endure risks. While nonviolent tactics like protests, strikes, and civil disobedience often build broader support and maintain moral high ground, armed conflict remains a last resort in the face of extreme oppression. Together, these tools have shaped the course of history, demonstrating the power of collective action in achieving political revolution.

Why Political Movements Collapse: Lessons from Failed Revolutions and Uprisings

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: French, Russian, and American revolutions illustrate diverse paths to political transformation

A political revolution involves a fundamental transformation of a state's political system, often marked by shifts in power structures, governance, and societal norms. Historical examples such as the French, Russian, and American revolutions highlight diverse paths to political transformation, each shaped by unique contexts, ideologies, and outcomes. These revolutions not only redefined their respective nations but also left lasting impacts on global political thought and practice.

The French Revolution (1789–1799) exemplifies a radical political upheaval driven by social inequality and Enlightenment ideals. Sparked by financial crisis and the Estates-General's convening, it began with the storming of the Bastille, symbolizing resistance to monarchical tyranny. The revolution abolished the monarchy, established a republic, and promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, emphasizing liberty, equality, and fraternity. However, it also descended into the Reign of Terror, where thousands were executed for perceived counter-revolutionary activities. The French Revolution's legacy lies in its challenge to feudalism and its promotion of democratic principles, though its path was marked by violence and instability.

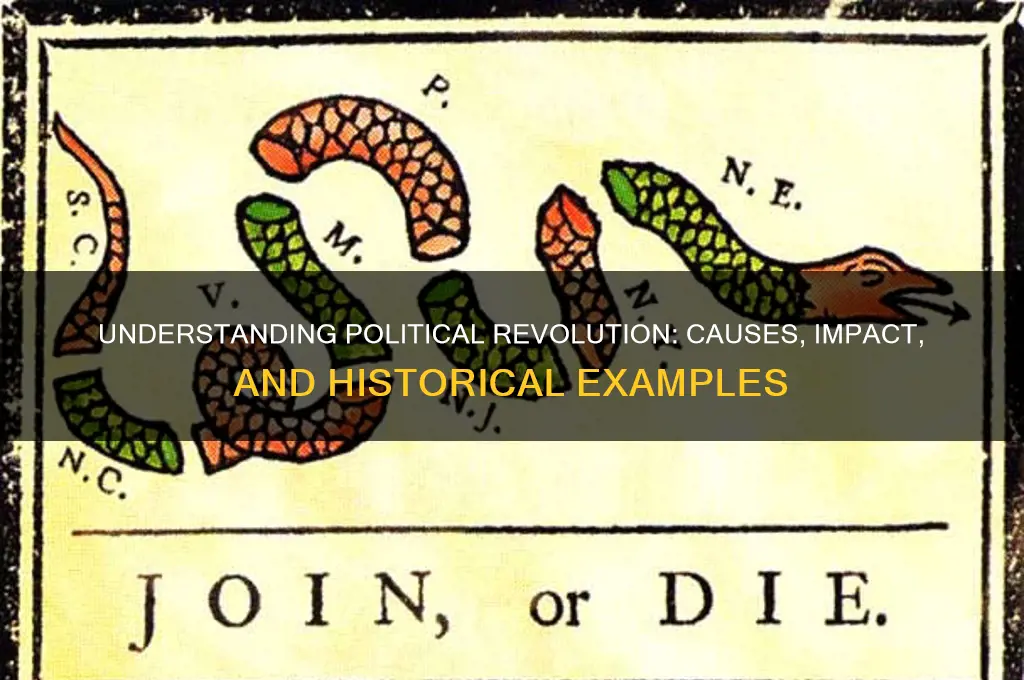

In contrast, the American Revolution (1775–1783) was a colonial rebellion against British rule, culminating in the establishment of a constitutional republic. Fueled by grievances over taxation without representation and British restrictions, it was less about social upheaval and more about political self-determination. The Declaration of Independence (1776) articulated Enlightenment ideals of natural rights and popular sovereignty. The revolution's success led to the creation of the United States Constitution, which institutionalized a system of checks and balances and federalism. Unlike the French Revolution, it was relatively less violent and focused on creating a stable, representative government rather than radical social transformation.

The Russian Revolution (1917) represents a Marxist-inspired political transformation that overthrew the Tsarist autocracy and established a socialist state. The February Revolution toppled Tsar Nicholas II, leading to a provisional government, while the October Revolution, led by the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin, ushered in communist rule. The revolution was driven by widespread discontent among peasants, workers, and soldiers, exacerbated by Russia's failures in World War I. It resulted in the creation of the Soviet Union, a one-party state committed to socialism and centralized planning. Unlike the French and American revolutions, the Russian Revolution sought to dismantle class structures entirely, though it led to decades of authoritarian rule and political repression.

These revolutions illustrate diverse paths to political transformation. The French Revolution was a violent, socially driven upheaval that prioritized abstract ideals; the American Revolution was a more controlled struggle for self-governance; and the Russian Revolution was an ideologically driven movement to establish a new economic and political order. Each revolution reflects the specific historical, social, and economic conditions of its time, demonstrating that political transformation can take varied forms, from democratic republics to socialist states, and can be achieved through both gradual reform and abrupt, revolutionary change. Together, they underscore the complexity and diversity of political revolutions as agents of change.

Navigating Political Differences: How to Keep Friendships Strong Amidst Disagreements

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Outcomes of Revolution: Regime change, new constitutions, and shifts in power dynamics redefine societies post-revolution

A political revolution fundamentally transforms the existing political system, often leading to profound and lasting changes in governance, power structures, and societal norms. One of the most immediate outcomes of such a revolution is regime change, where the ruling government or leadership is replaced, either through peaceful transition or forceful overthrow. This shift in power typically occurs when widespread dissatisfaction with the current regime reaches a tipping point, fueled by issues such as corruption, inequality, or oppression. The new regime may emerge from revolutionary movements, coalitions of opposition groups, or even external interventions. For instance, the French Revolution of 1789 replaced the monarchy with a republic, while the Iranian Revolution of 1979 ousted the Shah and established an Islamic theocracy. Regime change is not merely a transfer of power but a symbolic break from the past, signaling a new direction for the nation.

Following regime change, the establishment of a new constitution often becomes a cornerstone of post-revolutionary societies. A constitution serves as the framework for governance, outlining the rights of citizens, the structure of government, and the distribution of power. Revolutionary constitutions frequently reflect the ideals and aspirations of the movement, embedding principles such as democracy, equality, and justice. For example, the United States Constitution, drafted after the American Revolution, created a system of checks and balances to prevent tyranny, while the post-apartheid Constitution of South Africa enshrined human rights and racial equality. The process of drafting a new constitution can be contentious, as different factions within the revolutionary coalition may have competing visions for the future. However, once adopted, it provides a legal and ideological foundation for the new order.

Shifts in power dynamics are another critical outcome of political revolutions, as they redistribute authority among social, economic, and political groups. Revolutions often empower previously marginalized communities, dismantling entrenched hierarchies and creating opportunities for greater participation in public life. For instance, the Russian Revolution of 1917 transferred power from the aristocracy to the proletariat, while the Arab Spring uprisings sought to challenge authoritarian regimes and empower citizens. These shifts can also lead to the rise of new elites, who may consolidate power in ways that either advance or undermine the revolutionary ideals. Additionally, revolutions frequently alter the relationship between the state and its citizens, redefining notions of sovereignty, citizenship, and civic duty.

The economic landscape is also significantly reshaped in the aftermath of a revolution. Revolutionary governments often implement policies aimed at addressing the root causes of the uprising, such as land redistribution, nationalization of industries, or economic liberalization. For example, the Mexican Revolution led to agrarian reforms that redistributed land to peasants, while the Chinese Communist Revolution introduced a centrally planned economy. These changes can foster economic growth and reduce inequality, but they may also lead to instability or resistance from vested interests. The success of such policies depends on the revolutionary leadership's ability to balance ideological goals with practical realities.

Finally, political revolutions have profound cultural and social impacts, reshaping identities, values, and norms. Revolutionary ideologies often permeate education, media, and public discourse, fostering a new national narrative that celebrates the struggle for change. Symbols, holidays, and monuments commemorate the revolution, reinforcing its legacy in collective memory. However, revolutions can also lead to polarization and conflict, as societies grapple with the challenges of reconciliation and justice. The long-term outcomes of a revolution depend on the ability of the new regime to address the aspirations of its people while navigating the complexities of governance and global politics. In essence, the outcomes of revolution—regime change, new constitutions, and shifts in power dynamics—redefine societies by creating a new political, economic, and cultural order.

Are Political Parties Constitutional? Exploring Their Legal and Historical Basis

You may want to see also

Role of Leadership: Charismatic leaders mobilize masses, shape ideologies, and guide revolutionary processes effectively

A political revolution is a fundamental transformation of a state's political system, often involving a shift in power structures, governance, and ideologies. At the heart of such revolutions lies the pivotal role of leadership, particularly charismatic leaders who possess the ability to mobilize masses, shape ideologies, and guide revolutionary processes effectively. These leaders are not merely figureheads but catalysts who inspire collective action and articulate a vision that resonates with the aspirations of the people. Their influence is critical in galvanizing diverse groups toward a common goal, often in the face of entrenched opposition and systemic challenges.

Charismatic leaders excel in mobilizing masses by tapping into widespread discontent and channeling it into organized movements. Through powerful oratory, symbolic actions, and relatable narratives, they create a sense of urgency and possibility, convincing followers that radical change is not only necessary but achievable. Figures like Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, and Fidel Castro exemplify this ability, as they transformed disparate grievances into unified struggles for liberation or reform. Their personal magnetism and emotional appeal bridge the gap between abstract ideals and concrete action, turning passive observers into active participants in the revolutionary process.

Beyond mobilization, these leaders play a central role in shaping ideologies that define the revolution's purpose and direction. They distill complex political, social, and economic issues into coherent frameworks that provide clarity and purpose. For instance, Lenin's interpretation of Marxism guided the Bolshevik Revolution, while Martin Luther King Jr.'s emphasis on nonviolent resistance framed the Civil Rights Movement. By articulating a compelling ideology, charismatic leaders not only inspire but also educate, fostering a shared understanding among followers that sustains their commitment through adversity.

The guidance of revolutionary processes is another critical function of charismatic leadership. Revolutions are inherently chaotic, marked by uncertainty and conflict, and leaders must navigate these challenges with strategic acumen. This involves making difficult decisions, adapting to changing circumstances, and maintaining unity among diverse factions. Leaders like Mao Zedong during the Chinese Revolution and Simón Bolívar in Latin America demonstrated this ability by balancing ideological purity with pragmatic compromises, ensuring the revolution remained viable and focused. Their leadership ensures that the movement does not devolve into aimless rebellion but progresses toward tangible political transformation.

However, the effectiveness of charismatic leaders in political revolutions is not without risks. Their dominance can lead to cults of personality, undermining democratic principles and institutionalizing power. Moreover, the success of a revolution often hinges on the leader's ability to transition from revolutionary to governance roles, a challenge many have struggled with. Despite these risks, the role of charismatic leadership remains indispensable in political revolutions, as their unique abilities to mobilize, ideologize, and guide are often the difference between stagnation and transformative change. Without such leaders, many revolutions might lack the direction, inspiration, and cohesion needed to challenge established orders and forge new political realities.

Understanding Turkey's Political Landscape: Key Factors and Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political revolution is a fundamental and often rapid change in the political power structure, governance, or system of a country or region. It typically involves the overthrow or significant transformation of existing institutions, leadership, or ideologies, often driven by popular movements or mass mobilization.

While a political revolution focuses on changing the structures of government and power, a social or cultural revolution emphasizes shifts in societal norms, values, and behaviors. Political revolutions often accompany or lead to social changes, but their primary goal is to alter the political system itself.

Notable examples include the American Revolution (1775–1783), the French Revolution (1789–1799), the Russian Revolution (1917), and the Iranian Revolution (1978–1979). Each of these events resulted in significant changes to the political systems and power dynamics of their respective countries.