The question of whether political parties existed during the era of slavery is complex and varies depending on the region and time period in question. In the United States, for instance, the early years of the republic saw the emergence of political factions, such as the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, which later evolved into more formalized political parties. However, these parties' stances on slavery were often nuanced and shifting, with some members advocating for its abolition, while others defended its continuation. In the antebellum South, political parties like the Democrats and Whigs were deeply divided over the issue of slavery, with Southern factions often prioritizing the protection of slaveholder interests. Meanwhile, in other parts of the world where slavery was practiced, such as Brazil or the Caribbean, political parties as we understand them today were less developed, and political power was often concentrated in the hands of colonial authorities or local elites who benefited from the slave trade. Ultimately, the relationship between political parties and slavery is a multifaceted one, reflecting the complex social, economic, and ideological forces that shaped the institution of slavery across different historical contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Existence of Political Parties | Yes, political parties existed during the era of slavery in the U.S. |

| Major Parties | Democratic Party and Whig Party were the dominant parties in the 1800s. |

| Democratic Party Stance | Supported slavery, particularly in the South, as part of states' rights. |

| Whig Party Stance | Generally opposed the expansion of slavery but not its abolition. |

| Regional Divide | Southern politicians often prioritized slavery, while Northerners were more divided. |

| Key Figures | John C. Calhoun (pro-slavery Democrat), Abraham Lincoln (anti-slavery Whig/Republican). |

| Impact on Politics | Slavery was a central issue in political debates and party platforms. |

| Formation of Republican Party | Emerged in the 1850s as an anti-slavery party, leading to the Civil War. |

| Legislative Influence | Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Act were shaped by party politics. |

| Abolitionist Movements | Often aligned with or influenced Northern political parties. |

| End of Slavery | The Republican Party's rise and the Civil War led to the abolition of slavery in 1865. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early American Political Factions

The early years of the United States were marked by the emergence of political factions that laid the groundwork for the modern party system. Even during the era of slavery, these factions began to coalesce around differing visions of governance, economic policy, and the role of the federal government. While slavery itself was a contentious issue, it was not the sole defining factor of these early political divisions. Instead, factions formed based on broader ideological and regional differences, which would later intersect with the slavery debate.

Consider the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, the two dominant factions of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal role. These factions were not explicitly defined by their stance on slavery, but their policies and regional bases would later influence how the issue of slavery was addressed. For instance, the agrarian South, dominated by Democratic-Republicans, relied heavily on slave labor, while the more industrialized North, with its Federalist leanings, had a smaller stake in the institution.

Analyzing these factions reveals how regional economies and ideologies shaped political alignments. The Federalist emphasis on commerce and industry aligned with Northern interests, while the Democratic-Republican focus on agriculture resonated with the Southern planter class. Slavery, though not the central issue of these factions, became intertwined with their economic and regional priorities. This dynamic set the stage for later political divisions, as the question of slavery’s expansion or abolition became more pronounced in the mid-19th century.

To understand the evolution of these factions, examine their responses to key events like the Louisiana Purchase or the War of 1812. The Federalists opposed the Louisiana Purchase, fearing it would strengthen the agrarian South and dilute Northern influence. The Democratic-Republicans, however, embraced it as an opportunity to expand Southern and Western territories, which were heavily dependent on slave labor. These reactions highlight how regional and economic interests, rather than a unified stance on slavery, drove early political divisions.

In practical terms, studying these early factions provides insight into the roots of modern political polarization. By tracing how economic and regional differences shaped alliances, we can better understand why certain regions or groups later became strongholds for pro-slavery or abolitionist movements. For educators or historians, emphasizing these nuances helps students grasp the complexity of early American politics, moving beyond simplistic narratives of "North vs. South" or "pro-slavery vs. anti-slavery." Instead, it reveals a multifaceted landscape where factions formed around broader ideologies that indirectly influenced their later positions on slavery.

Are Local Political Parties Nonprofits? Exploring Their Legal Status

You may want to see also

Slaveholder Influence on Parties

During the era of slavery in the United States, slaveholders wielded significant influence over political parties, shaping their platforms, policies, and leadership. The Democratic Party, in particular, became a stronghold for slaveholder interests, especially in the South. This influence was not merely ideological but deeply structural, as slaveholders dominated state legislatures, congressional delegations, and even the presidency. For instance, seven of the first ten U.S. presidents were slaveholders, and their political decisions often reflected the economic and social priorities of the slaveholding class. This dominance ensured that the Democratic Party, which controlled the South, consistently defended slavery as a vital institution, framing it as essential to the nation’s economy and social order.

The Whig Party, though less uniformly pro-slavery, also felt the pressure of slaveholder influence. While Whigs in the North often focused on economic modernization and internal improvements, their Southern counterparts were constrained by the need to appease slaveholders. This internal divide weakened the Whigs, as they struggled to balance the interests of Northern industrialists and Southern planters. The inability to present a unified front on the issue of slavery ultimately contributed to the party’s collapse in the 1850s. Meanwhile, the emergence of the Republican Party in the 1850s, which explicitly opposed the expansion of slavery, marked a significant shift in the political landscape. However, even this party had to tread carefully, as its leaders sought to avoid alienating border states with significant slaveholder populations.

Slaveholders’ influence extended beyond party platforms to the very mechanics of politics. The Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation and taxation, gave slaveholding states disproportionate power in Congress. This structural advantage allowed Southern politicians to block anti-slavery legislation and shape national policies in their favor. Additionally, the gag rule in the House of Representatives, enforced from 1836 to 1844, prevented debates on anti-slavery petitions, effectively silencing Northern opposition. These measures illustrate how slaveholders not only controlled their own party but also manipulated political institutions to maintain their grip on power.

To understand the depth of slaveholder influence, consider the 1860 presidential election. The Democratic Party split into Northern and Southern factions, with the Southern Democrats nominating John C. Breckinridge, a staunch defender of slavery. This division paved the way for Abraham Lincoln’s victory, despite his name not appearing on ballots in many Southern states. The election highlighted the extent to which slaveholders had polarized the nation’s politics, as their insistence on protecting slavery drove the South toward secession. This example underscores how slaveholder influence was not just a feature of political parties but a driving force behind the nation’s descent into civil war.

Practical takeaways from this historical dynamic are clear: political parties are not immune to the interests of powerful economic groups. In the case of slavery, the alignment of the Democratic Party with slaveholder interests demonstrates how institutions can be co-opted to perpetuate systemic injustices. Modern parallels can be drawn to the influence of industries like fossil fuels or pharmaceuticals on contemporary politics. To counter such influences, transparency in political funding, robust public debate, and the empowerment of marginalized voices are essential. By studying the past, we can better navigate the present and build a more equitable future.

Which Political Party Opposes Abortion Rights in the US?

You may want to see also

Abolitionists and Party Alignment

The abolitionist movement in the United States was a powerful force for change, but its relationship with political parties was complex and often fraught. While abolitionists shared a common goal—the eradication of slavery—their strategies and alliances varied widely, reflecting the diverse ideologies and priorities within the movement. This diversity made party alignment a challenging yet crucial aspect of their political engagement.

Consider the Liberty Party, founded in 1840, as one of the earliest political parties dedicated solely to abolition. It emerged from the frustration of activists who felt that existing parties, like the Whigs and Democrats, were too compromised by their need to appeal to both Northern and Southern voters. The Liberty Party’s platform was radical for its time, advocating not only for the immediate end of slavery but also for equal rights for African Americans. However, its single-issue focus limited its appeal, and it struggled to gain traction beyond a small, dedicated base. This example illustrates how abolitionists sometimes prioritized ideological purity over political pragmatism, a choice that had both strengths and limitations.

In contrast, the Republican Party, formed in the 1850s, offers a different model of abolitionist alignment. While not exclusively an abolitionist party, the Republicans incorporated anti-slavery sentiments into a broader platform that included economic and modernization policies. This strategic broadening allowed them to attract a wider coalition, including former Whigs, Free Soilers, and even some Democrats disillusioned with their party’s pro-slavery stance. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, a Republican, marked a turning point, as it demonstrated how abolitionist goals could be advanced through a major party with a more inclusive agenda. This approach highlights the importance of balancing ideological commitment with political viability.

However, not all abolitionists embraced party politics. Figures like William Lloyd Garrison, editor of *The Liberator*, argued that political parties were inherently corrupt and that moral persuasion, not legislative action, was the only legitimate path to abolition. Garrison’s rejection of party alignment underscores a tension within the movement: the struggle between purity and practicality. While his stance inspired many through its uncompromising morality, it also limited his influence in shaping policy.

For modern activists, the lessons from abolitionists’ party alignment are clear. First, recognize the value of both single-issue parties and broader coalitions. Single-issue parties can keep urgent causes in the spotlight, but broader coalitions often have the power to enact meaningful change. Second, balance ideological commitment with strategic flexibility. Purity is inspiring, but pragmatism is often necessary to achieve tangible results. Finally, understand that political engagement is just one tool in the activist’s toolkit. Moral persuasion and grassroots organizing remain vital complements to party politics. By studying the abolitionist movement, we gain insights into how to navigate the complexities of political alignment in pursuit of justice.

Discover Your Political Identity: Uncover Your Faction in Today's Landscape

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$1.99 $14.95

$41.98 $49.95

$78 $95

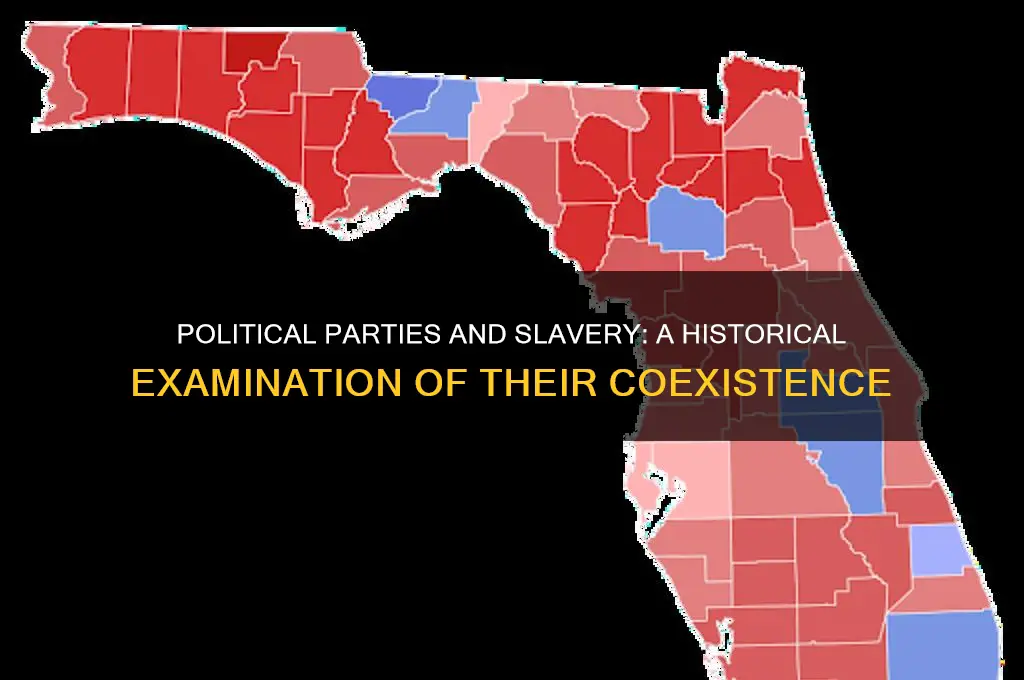

Regional Party Differences

During the era of slavery in the United States, regional differences profoundly shaped the emergence and evolution of political parties. The North and South, divided by economic interests and moral stances on slavery, fostered distinct party systems that reflected their unique priorities. In the North, where industrialization and wage labor dominated, political parties like the Whigs and later the Republicans often emphasized economic modernization, infrastructure development, and the gradual abolition of slavery. In contrast, the South, reliant on plantation agriculture and enslaved labor, saw the rise of parties like the Democrats, who staunchly defended slavery as essential to their economy and way of life.

Consider the Democratic Party, which, by the mid-19th century, had become the dominant political force in the South. Its platform was explicitly pro-slavery, advocating for the expansion of slavery into new territories and the protection of slaveholders' rights. Southern Democrats viewed slavery not merely as a moral issue but as a cornerstone of their economic and social order. This regional alignment was so strong that Southern Democrats often threatened secession if their pro-slavery agenda was challenged, a stance that would eventually contribute to the Civil War.

In the North, the Republican Party emerged in the 1850s as a direct response to the Democratic Party's pro-slavery policies. Republicans, while not uniformly abolitionist, opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, arguing that it would undermine free labor and hinder economic progress. This regional party difference was not just ideological but also practical: Northern Republicans sought to limit the South's political power by restricting the spread of slavery, thereby preserving the North's economic and demographic advantages.

These regional party differences were further exacerbated by the issue of states' rights versus federal authority. Southern politicians, regardless of party affiliation, often championed states' rights as a means to protect slavery from federal interference. Northern parties, on the other hand, tended to support a stronger federal government to promote national unity and economic development. This divide was evident in debates over tariffs, internal improvements, and the admission of new states, where regional interests consistently clashed.

Understanding these regional party differences is crucial for grasping the complexities of American politics during the slavery era. It highlights how economic systems, moral beliefs, and regional identities shaped political alliances and conflicts. For instance, while both the North and South had Democratic and Whig parties, their platforms and priorities differed dramatically based on regional needs. This regional polarization ultimately made compromise difficult, setting the stage for the nation's eventual fracture over the issue of slavery.

To analyze this further, consider the 1860 presidential election, where regional party differences reached a breaking point. The Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, won without a single Southern electoral vote, while the Democratic Party split into Northern and Southern factions, each advocating for their region's interests. This election exemplifies how regional party differences not only defined political strategies but also foreshadowed the secession crisis and the Civil War. By examining these regional distinctions, we gain insight into the deep-rooted divisions that characterized American politics during the slavery era.

Disagreeing with Your Political Party: Consequences and Navigating Dissent

You may want to see also

Pre-Civil War Party Platforms

The antebellum period in American politics was a cauldron of ideological clashes, with slavery as the central issue shaping party platforms. The Democratic Party, rooted in the legacy of Andrew Jackson, championed states’ rights and agrarian interests, often aligning with Southern slaveholders. Their 1848 platform explicitly defended the expansion of slavery into new territories, arguing it was essential to protect Southern economic and social structures. In contrast, the Whig Party, though internally divided, focused on economic modernization and national unity, often sidestepping the slavery question to avoid alienating either section. This strategic ambiguity, however, proved unsustainable as the slavery debate intensified.

The emergence of the Free Soil Party in 1848 marked a pivotal shift, as it directly opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories while stopping short of advocating abolition. Their platform, encapsulated in the slogan "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men," appealed to Northern workers who feared competition from slave labor. This party laid the groundwork for the Republican Party, which formed in 1854 and took a firmer stance against slavery’s expansion. The Republicans’ platform, though not abolitionist, argued that slavery was morally wrong and economically detrimental to free labor, positioning it as a threat to Northern prosperity.

The American (Know-Nothing) Party, another pre-Civil War faction, initially focused on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments but eventually addressed slavery. Their 1856 platform adopted a stance of "non-intervention," leaving the issue to the states, which effectively aligned them with pro-slavery interests. This position alienated Northern members and contributed to the party’s rapid decline, highlighting the difficulty of maintaining neutrality in an increasingly polarized political landscape.

Analyzing these platforms reveals how slavery forced parties to define themselves in relation to it, whether through outright defense, cautious opposition, or attempted neutrality. The Democrats’ pro-slavery stance solidified their Southern base but alienated Northern voters, while the Whigs’ evasion of the issue led to their dissolution. The Free Soil and Republican platforms, by contrast, harnessed Northern economic anxieties and moral objections to slavery, reshaping the political map. These pre-Civil War party platforms were not just policy statements but reflections of deeper societal divisions that would ultimately tear the nation apart.

Should You Host a Party When Sick? Etiquette and Health Considerations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, political parties existed during the era of slavery in the United States, particularly in the 19th century. The two dominant parties were the Democratic Party and the Whig Party, which later gave way to the Republican Party in the 1850s.

Yes, political parties had differing stances on slavery. The Democratic Party generally supported the expansion of slavery, while the Whig Party was more divided. The Republican Party, formed in the 1850s, explicitly opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories.

Slavery was a major factor in the realignment of political parties. The issue of slavery in new territories led to the collapse of the Whig Party and the rise of the Republican Party, which united anti-slavery forces. It also deepened divisions within the Democratic Party between northern and southern factions.

Yes, political parties played a significant role in the abolition of slavery. The Republican Party, led by figures like Abraham Lincoln, pushed for policies that ultimately led to the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in 1865. The Democratic Party, particularly its southern wing, opposed these efforts.