The Japanese internment camps were a result of Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942, which authorized the removal of people of Japanese ancestry from designated military areas in the United States. This order led to the forced relocation and imprisonment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans, most of whom were U.S. citizens, in internment camps during World War II. The constitutionality of these camps has been a subject of debate, with the Supreme Court upholding the camps' constitutionality in the controversial Korematsu v. United States decision in 1944, which was only formally overturned in 2018.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The violation of constitutional rights

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II sparked a constitutional crisis and a political debate. The US government's decision to forcibly relocate and incarcerate about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) raised serious questions about the violation of constitutional rights.

The Roosevelt administration's policy, driven by anti-Japanese suspicion and fear following the Pearl Harbor attack, resulted in the loss of personal liberties, homes, and property for Japanese Americans, regardless of their citizenship status. The incarceration and the associated exclusion orders violated the constitutional rights of those affected, including the right to due process and protection from racial discrimination. The Supreme Court's rulings in Korematsu v. United States and Hirabayashi v. United States upheld the federal government's war powers and the validity of exclusion orders, but they sidestepped the direct question of the constitutionality of incarcerating citizens without due process.

The Court's decision in Ex parte Endo, however, acknowledged that loyal citizens could not be detained indefinitely, paving the way for Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast. The incarceration also resulted in terrible living conditions, with families housed in makeshift camps offering little privacy or protection from the elements. The barbed-wire fences and guard towers surrounding the camps further emphasized the loss of freedom for those incarcerated.

Unsafe Confined Space Entry: What Are the Red Flags?

You may want to see also

The legality of Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland. This order resulted in the incarceration of about 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA).

The constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 was challenged in court by Japanese Americans, notably including Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Mitsuye Endo. In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Mitsuye Endo that the War Relocation Authority did not have the power to detain citizens who were not charged with disloyalty or subversiveness for an extended period. This ruling led to the release of detainees and the closure of most camps by the end of 1945.

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed the Evacuation Claims Act, which allowed internees to file claims for property lost due to relocation. The issue of the legality and injustice of the incarceration was revisited in the 1980s, with the establishment of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). CWRIC conducted investigations and concluded that the incarceration was not justified by military necessity but rather by "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership". Based on CWRIC's recommendations, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which acknowledged the grave injustice done to Japanese Americans and provided for partial restitution and a public education fund to prevent similar incidents in the future.

On February 19, 1976, President Gerald Ford formally rescinded Executive Order 9066 and apologized for the internment, acknowledging the loyalty and contributions of Japanese Americans to the nation.

US Code and Constitution: What's the Relationship?

You may want to see also

The government's justification for the camps

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, launched the United States fully into World War II. This attack also sparked a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment across the United States, particularly on the West Coast, where about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry lived, most of them full citizens.

The government's justification for the internment camps was primarily based on national security concerns. The Office of Naval Intelligence and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had been conducting surveillance on Japanese Americans since the 1930s, and after the Pearl Harbor attack, they arrested thousands of suspected subversives, including many Japanese Americans. The government argued that the internment camps were necessary to protect against potential enemy agents and to prevent espionage.

Additionally, the government cited the need to protect Japanese Americans from potential backlash and violence due to the heightened anti-Japanese sentiment. Martial law was declared in Hawaii, and military orders were issued, specifically targeting persons of Japanese ancestry. The government also pointed to the success of similar civilian internment policies employed in other circumstances, such as the internment of indigenous Cherokee, Dakota, and Navajo peoples during the 19th century.

The Roosevelt administration's drastic policy towards Japanese Americans, both alien and citizen, was influenced by the widespread fear and suspicion that followed the Pearl Harbor attack. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, authorizing the Secretary of War and military commanders to evacuate all persons deemed a threat from the West Coast to internment camps, referred to as "relocation centers." The government's rhetoric emphasized military necessity and national security, and many accepted the justification for the camps without questioning the motivations behind them.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II remains a controversial and shameful episode in American history, sparking constitutional and political debates. The government's actions violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans, and the 1983 report, "Personal Justice Denied," found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty, concluding that internment was primarily driven by racism.

Life Tenure: The Supreme Court's Constitutional Conundrum

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.19 $16

The living conditions in the camps

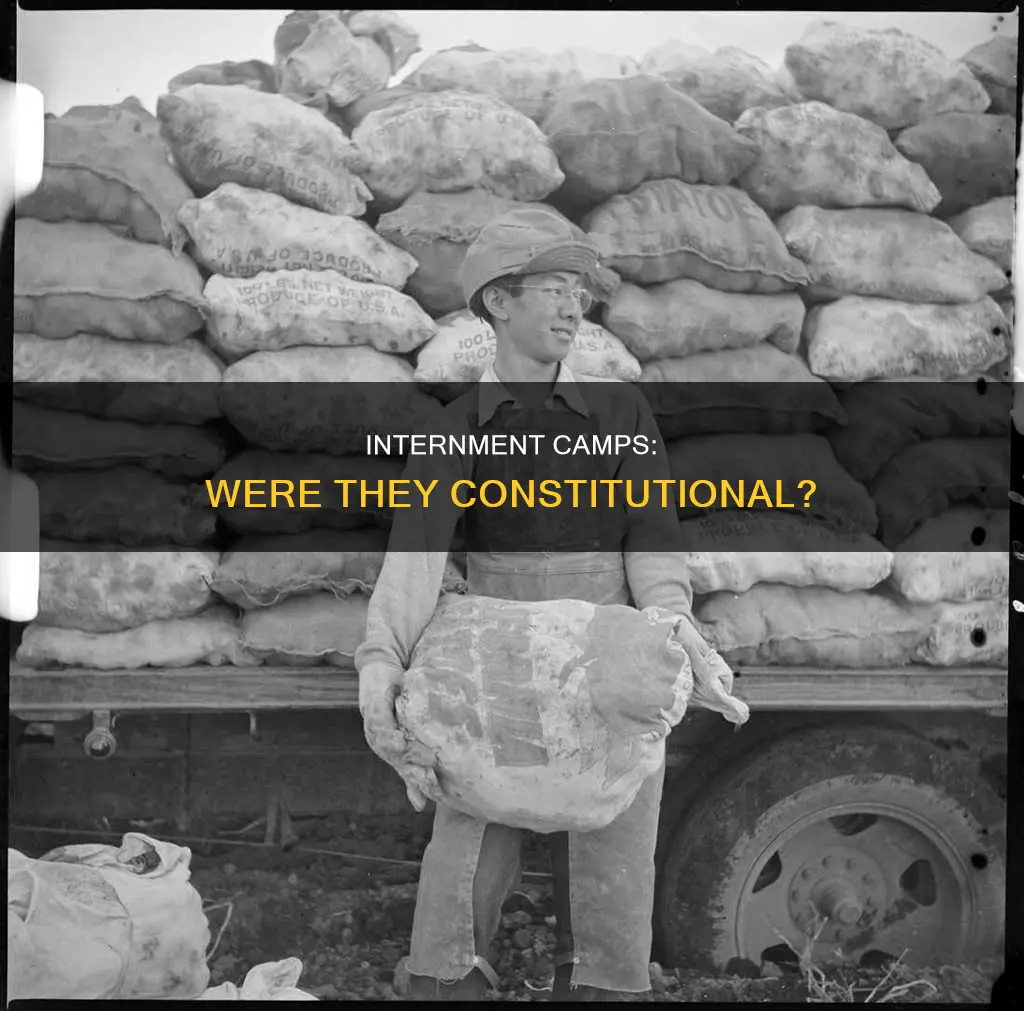

The living conditions in the Japanese internment camps were harsh and cramped, with little regard for privacy or family life. The camps were established by the War Relocation Authority, with 10 permanent camps set up, mostly in the West, and two in Arkansas. These camps were surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, with armed guards posted to prevent inmates from leaving.

The "`assembly centres'" and "`relocation centres'" (also known as internment camps) were often hastily built to military barracks specifications, making them poorly equipped for families. Twenty-five people were sometimes forced to live in spaces designed for four. Families were housed together in army-style barracks, with little protection from the elements and sparse furnishings. Each family had very limited space for their clothing and possessions. The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in Wyoming, for example, had unpartitioned toilets and cots for beds. The daily food budget was just 45 cents per person.

Despite these conditions, the incarcerated Japanese Americans tried to make the camps feel like home. They established newspapers, markets, schools, police and fire departments, bands, sports teams, clubs, and activities. Some inmates were allowed to leave to attend college or to work elsewhere in the US.

The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II sparked constitutional and political debate, with three Japanese-American citizens challenging the constitutionality of the forced relocation and curfew orders through legal action. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, and the remaining survivors of the camps were sent formal letters of apology and were awarded $20,000 in restitution.

Interpreting the Constitution: Democratic Republicans' Vision

You may want to see also

The release of internees and compensation

The release of Japanese Americans from the internment camps began in 1943, when 4,000 students were allowed to leave and attend college. In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled that loyal citizens could not be detained, and on December 17, the exclusion orders were rescinded. Nine of the ten camps were shut down by the end of 1945, as World War II drew to a close.

While some Japanese Americans returned to their hometowns, others sought new surroundings. For example, of the Japanese-American community of Tacoma, Washington, who had been sent to three different centers, only 30 percent returned to Tacoma after the war. On the other hand, 80 percent of Japanese Americans from Fresno who had been sent to Manzanar returned to their hometown.

In 1988, Congress passed and President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which acknowledged the injustice of "internment," apologized for it, and provided a $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated. The Justice Department's Office of Redress Administration (ORA) was charged with administering the ten-year program, which closed in 1999 after paying out more than $1.6 billion to over 82,250 people of Japanese ancestry who were interned during World War II.

Foundations of Freedom: Guarding Tyranny with the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps, mostly in the western interior of the country. Two-thirds of those incarcerated were U.S. citizens.

The Supreme Court upheld the legality of the internment camps, citing the war powers of the federal government as justification. However, the Court's ruling did not directly address the constitutionality of the federal law authorizing the internment, and many argue that the camps violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans.

Living conditions in the camps were terrible, with families living in cramped and inadequate barracks, offering little privacy or protection from the elements. Despite these conditions, Japanese Americans did their best to make the camps feel like home, forming bands, sports teams, and clubs. The incarceration also had significant economic impacts, with homeowners and businessmen suffering an estimated total property loss of $1.3 billion. In 1988, Congress acknowledged the injustice of the incarceration and provided partial restitution, including $20,000 cash payments to each person who was incarcerated.