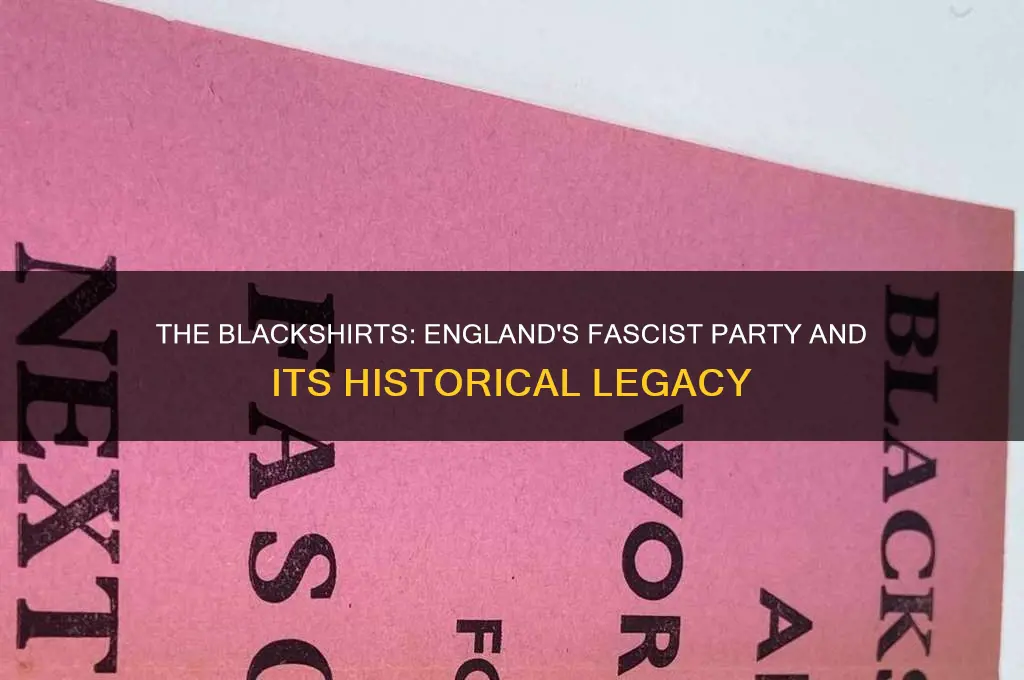

The question of whether there was a political party in England called the Blackshirts often arises in discussions about the country's political history, particularly in the context of the 1930s. While England did not have a formal political party named the Blackshirts, the British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, adopted the black shirt as its uniform, drawing parallels with Benito Mussolini's Italian Fascists. Founded in 1932, the BUF sought to establish a fascist regime in the UK, promoting nationalism, anti-Semitism, and corporatism. Although the BUF never gained significant electoral success, its street violence, particularly during the 1936 Battle of Cable Street, left a lasting impact on British society. The organization was eventually banned in 1940 under Defence Regulation 18B, as part of the government's efforts to suppress fascist activities during World War II.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | British Union of Fascists (BUF) |

| Commonly Known As | The Blackshirts |

| Leader | Sir Oswald Mosley |

| Founded | 1932 |

| Dissolved | 1940 (banned under Defence Regulation 18B) |

| Ideology | Fascism, Ultranationalism, Anti-Communism, Corporatism |

| Symbol | Flash and Circle (inspired by Italian Fascism) |

| Uniform | Black shirts (hence the nickname), black trousers, and black boots |

| Peak Membership | Approximately 50,000 members in the mid-1930s |

| Notable Events | The Battle of Cable Street (1936), where anti-fascist protesters clashed with the BUF and police |

| Political Influence | Limited electoral success; never won a seat in Parliament |

| Legacy | Largely discredited and marginalized after World War II due to association with Nazi Germany |

| Current Status | Defunct; no direct successor party exists |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origins of the British Union of Fascists (BUF)

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) emerged in the early 1930s as a direct response to the economic and social upheaval of the Great Depression. Founded in 1932 by Sir Oswald Mosley, a former Conservative and Labour politician, the BUF sought to capitalize on widespread discontent by offering a radical alternative to the established political order. Mosley, disillusioned with mainstream politics, admired Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy and modeled the BUF after it, adopting the blackshirt uniform as a symbol of discipline and authority. This choice of attire was not merely aesthetic but a deliberate attempt to evoke strength and unity, mirroring the Italian Fascists’ paramilitary style.

Mosley’s vision for the BUF was rooted in his belief that Britain needed a strong, centralized leadership to address its economic woes. The party’s manifesto, *The Greater Britain*, proposed a corporatist state where industry and government would collaborate to eliminate unemployment and restore national pride. To attract followers, Mosley employed modern propaganda techniques, including mass rallies, catchy slogans, and a focus on youth engagement. The BUF’s early success was notable, particularly in London’s East End, where it exploited anti-immigrant sentiment and promised jobs for British workers. However, this rise was short-lived, as the party’s violent tactics and fascist ideology alienated much of the public.

A critical turning point for the BUF was the 1934 Olympia rally, intended to showcase the party’s strength. Instead, it backfired spectacularly when Mosley’s blackshirts violently clashed with anti-fascist protesters, leading to widespread public outrage. This event, coupled with the government’s 1936 Public Order Act, which banned political uniforms and restricted marches, severely crippled the BUF’s ability to operate openly. Despite these setbacks, the party persisted, rebranding itself as the British Union in 1937, though it never regained its earlier momentum.

Comparatively, the BUF’s origins highlight the allure of fascism in interwar Europe, but also its inherent flaws. Unlike Mussolini’s Fascists, who seized power in a nation grappling with post-war chaos, Mosley’s movement faced a more stable British society less receptive to authoritarian solutions. The BUF’s failure underscores the importance of context in political movements: while fascism found fertile ground in some European countries, Britain’s democratic traditions and public aversion to extremism ultimately stifled its growth. This historical episode serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of demagoguery and the resilience of democratic institutions.

Castle Rock Mayors: Political Party Affiliations Explained

You may want to see also

Role of Oswald Mosley in leading the BUF

Oswald Mosley's leadership of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) was marked by a blend of charisma, strategic ambition, and ideological rigidity. As the founder and figurehead, Mosley sought to replicate the authoritarian models of Mussolini and Hitler, tailoring fascism to a British context. His role was not merely symbolic; he was the architect of the BUF's policies, the driving force behind its public image, and the primary decision-maker in its organizational structure. Mosley's aristocratic background and former parliamentary experience lent the BUF a veneer of legitimacy, though his extreme views ultimately alienated mainstream British society.

To understand Mosley's leadership, consider his three-pronged approach: ideological purity, public spectacle, and political maneuvering. First, he insisted on strict adherence to fascist principles, including corporatism, nationalism, and anti-communism. This ideological rigidity, however, limited the BUF's appeal, as it failed to adapt to the pragmatic concerns of the British working class. Second, Mosley orchestrated high-profile rallies and marches, often featuring the black-shirted uniform that became synonymous with the party. These events were designed to project strength and discipline but frequently descended into violence, notably during the 1936 Battle of Cable Street, where anti-fascist protesters clashed with BUF supporters. Third, Mosley attempted to infiltrate mainstream politics by courting disaffected Conservatives and Labour voters, yet his overt authoritarianism and anti-Semitic rhetoric ensured the BUF remained a fringe movement.

A comparative analysis reveals Mosley's leadership style as both ambitious and flawed. Unlike Mussolini, who successfully consolidated power in Italy, Mosley lacked the political acumen to navigate Britain's democratic institutions. His failure to secure parliamentary seats or build lasting alliances underscored his inability to translate fascist ideology into electoral success. Similarly, while Hitler's rise was fueled by economic crisis and nationalist fervor, Mosley's attempts to exploit Britain's interwar economic struggles fell flat, as his solutions were perceived as extreme and unworkable. Mosley's leadership, therefore, exemplifies the tension between ideological purity and political pragmatism, a tension that ultimately doomed the BUF.

Practically speaking, Mosley's role offers a cautionary tale for modern political movements. His emphasis on spectacle over substance, and his refusal to moderate his views, alienated potential supporters and galvanized opposition. For instance, his decision to align the BUF with Nazi Germany during the 1930s alienated even sympathetic conservatives, while his anti-Semitic campaigns repelled the broader public. Leaders today might note the importance of balancing ideological conviction with adaptability, and of recognizing the limits of authoritarian tactics in democratic societies. Mosley's failure was not just one of policy but of understanding the cultural and political landscape he sought to dominate.

In conclusion, Oswald Mosley's leadership of the BUF was characterized by a combination of strategic vision and fatal misjudgment. His role as the party's undisputed leader shaped its trajectory, from its early growth to its eventual marginalization. While his efforts to establish fascism in Britain were ultimately unsuccessful, they provide a critical case study in the dynamics of extremist movements. By examining Mosley's leadership, we gain insight into the challenges of translating radical ideologies into political power, and the enduring importance of public perception and pragmatic adaptation in shaping a movement's fate.

Judicial Elections: Do Political Party Labels Appear on the Ballot?

You may want to see also

Uniform and symbolism of the Blackshirts

The British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, adopted the moniker "Blackshirts" as a direct homage to Mussolini’s Italian fascist movement. Their uniform—a black shirt, black trousers, and a black cap—was more than a sartorial choice; it was a calculated tool of intimidation and identity. The color black, historically associated with authority and formality, here symbolized rebellion against democratic norms and a commitment to authoritarian ideals. Unlike the khaki or olive uniforms of traditional military forces, the black ensemble deliberately set the Blackshirts apart, signaling their rejection of mainstream political structures.

Analyzing the symbolism, the uniform’s design mirrored fascist aesthetics across Europe, particularly Italy’s *Camicie Nere*. The shirt itself, often worn with a black tie and armband bearing the BUF’s silver flash-and-circle emblem, served as a visual manifesto. This emblem, combining a flash of lightning with a circle, represented dynamism and unity—core fascist principles. The armband, positioned prominently on the left arm, ensured the symbol was visible in salutes, reinforcing loyalty to the cause. Notably, the uniform’s simplicity made it accessible to working-class recruits, while its starkness conveyed discipline and uniformity, key to fascist ideology.

Practical considerations also shaped the uniform. The black shirt, typically made of durable cotton, was affordable and easy to maintain, reflecting the BUF’s need to outfit a growing membership on a tight budget. Boots, though not standardized, were often black and heavy, adding to the menacing appearance. For public rallies, members carried batons or flags, further amplifying their presence. Women in the movement wore black blouses and skirts, maintaining the color scheme while adhering to gendered norms of the time. These choices were not arbitrary; they were designed to create a cohesive, recognizable force capable of projecting strength.

Comparatively, the Blackshirts’ uniform contrasted sharply with the attire of contemporaneous British political groups. While Labour and Conservative activists relied on badges or banners, the BUF’s uniform was a full-body statement, akin to a military regiment. This militarization of dress was intentional, blurring the line between political activism and paramilitary activity. The uniform’s impact was psychological: it fostered a sense of brotherhood among members and fear among opponents, particularly during street clashes in the 1930s. However, this very uniformity became a liability, as it made members easily identifiable targets for anti-fascist counter-protests.

In conclusion, the Blackshirts’ uniform and symbolism were central to their identity and strategy. By adopting a distinct, militaristic dress code, the BUF sought to embody fascism’s ideals of order, strength, and unity. While the uniform succeeded in creating a formidable image, it also underscored the movement’s alienation from mainstream British society. Today, the black shirt remains a historical artifact, a reminder of fascism’s attempt to reshape politics through visual dominance. For those studying political symbolism, the Blackshirts offer a case study in how clothing can both unite and divide.

Strategies Political Parties Employ to Secure and Maintain Power

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Opposition and decline of the BUF in the 1930s

The British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, emerged in the 1930s as a far-right political party inspired by European fascism. Known for their blackshirted uniforms, they sought to capitalize on economic discontent and nationalism. However, their rise was met with fierce opposition, which, coupled with internal weaknesses, led to their decline by the end of the decade.

One of the most significant factors in the BUF's downfall was the widespread public and political opposition they faced. The Battle of Cable Street in 1936 epitomized this resistance. Thousands of anti-fascist protesters, including trade unionists, communists, and Jewish communities, clashed with BUF supporters and police, blocking Mosley's planned march through London's East End. This event not only disrupted the BUF's ability to mobilize but also tarnished their public image, portraying them as divisive and dangerous. The government responded by passing the Public Order Act of 1936, which banned political uniforms and restricted marches, directly targeting the BUF's tactics and symbolism.

Internally, the BUF struggled with organizational inefficiency and financial instability. Mosley's authoritarian leadership alienated many members, while the party's failure to secure significant electoral gains demoralized its base. Despite attracting initial interest during the Great Depression, the BUF's extremist rhetoric and violent tactics alienated moderate supporters. By the late 1930s, membership had dwindled, and the party's influence was confined to small, isolated pockets.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 delivered the final blow to the BUF. Mosley's pro-German stance and calls for peace with Nazi Germany were met with widespread outrage. The government, viewing the BUF as a threat to national security, arrested Mosley and other key figures under Defence Regulation 18B in 1940. The party was effectively dismantled, and its remnants were marginalized.

In retrospect, the BUF's decline was a result of both external resistance and internal failings. Public opposition, legislative measures, and the party's inability to adapt to changing political realities ensured its downfall. The legacy of the BUF serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of extremist movements in the face of unified societal resistance and effective governance.

The Political Roots Behind the Rise of the Enforcer

You may want to see also

Historical legacy and impact of the Blackshirts in England

The British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, was indeed the political entity in England commonly associated with the term "Blackshirts," derived from their paramilitary-style uniform. Founded in 1932, the BUF sought to emulate Italian Fascism, adopting its aesthetics and rhetoric but tailoring its message to British nationalism. While the BUF never achieved significant electoral success, its legacy is marked by its role in normalizing far-right ideologies in interwar Britain and its violent clashes with anti-fascist groups, most notably the 1936 Battle of Cable Street.

Analytically, the Blackshirts’ impact lies in their ability to galvanize both support and opposition, polarizing British society. Their rallies, often met with fierce resistance, highlighted the growing tension between fascism and democracy in the 1930s. The BUF’s anti-Semitic and xenophobic rhetoric resonated with a minority of Britons disillusioned by economic hardship and political instability, but their rise also spurred the formation of broad-based anti-fascist coalitions. This period underscores the importance of grassroots activism in countering extremist movements, a lesson still relevant today.

Instructively, studying the Blackshirts offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked extremism. Their ability to exploit societal fears and economic grievances serves as a reminder that democracies must remain vigilant against the erosion of civil liberties and the normalization of hate speech. Educators and policymakers can use this history to teach critical thinking and resilience against propaganda, emphasizing the role of media literacy in identifying and combating extremist narratives.

Comparatively, the Blackshirts’ legacy contrasts sharply with the post-war consensus in Britain, which prioritized social welfare and multiculturalism. While the BUF’s influence waned after World War II, their existence remains a stark reminder of the fragility of democratic institutions. Unlike fascist movements in continental Europe, the Blackshirts never seized power, but their brief ascendancy left an indelible mark on Britain’s political memory, shaping its approach to extremism and tolerance.

Descriptively, the Blackshirts’ uniform—black shirts, boots, and armbands—became a symbol of intimidation and division. Their marches through East London, a diverse and predominantly working-class area, were met with defiance from Jewish, Irish, and communist communities. The Battle of Cable Street, where protesters erected barricades to block a BUF march, remains a powerful symbol of unity against fascism. This visual and historical imagery continues to inspire anti-fascist movements, demonstrating the enduring power of collective resistance.

In conclusion, the Blackshirts’ historical legacy in England is one of polarization, resistance, and caution. Their brief but impactful existence serves as a case study in the rise and fall of extremist movements, offering lessons on the importance of vigilance, activism, and education. While their political influence was limited, their role in shaping Britain’s anti-fascist identity and democratic values remains a critical chapter in the nation’s history.

Exploring America's Dominant Political Parties: Democrats vs. Republicans

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, was commonly referred to as the Blackshirts due to the uniforms worn by its paramilitary wing.

The BUF was active from 1932 to 1940, gaining prominence in the 1930s before being banned under Defence Regulation 18B during World War II.

The Blackshirts advocated for fascism, nationalism, and anti-communism, aiming to establish a corporatist state and promote British imperialism while opposing democracy and socialism.

The Blackshirts faced widespread opposition, including violent clashes with anti-fascist groups like the Battle of Cable Street in 1936. The government eventually banned the party in 1940 due to its ties to Nazi Germany.