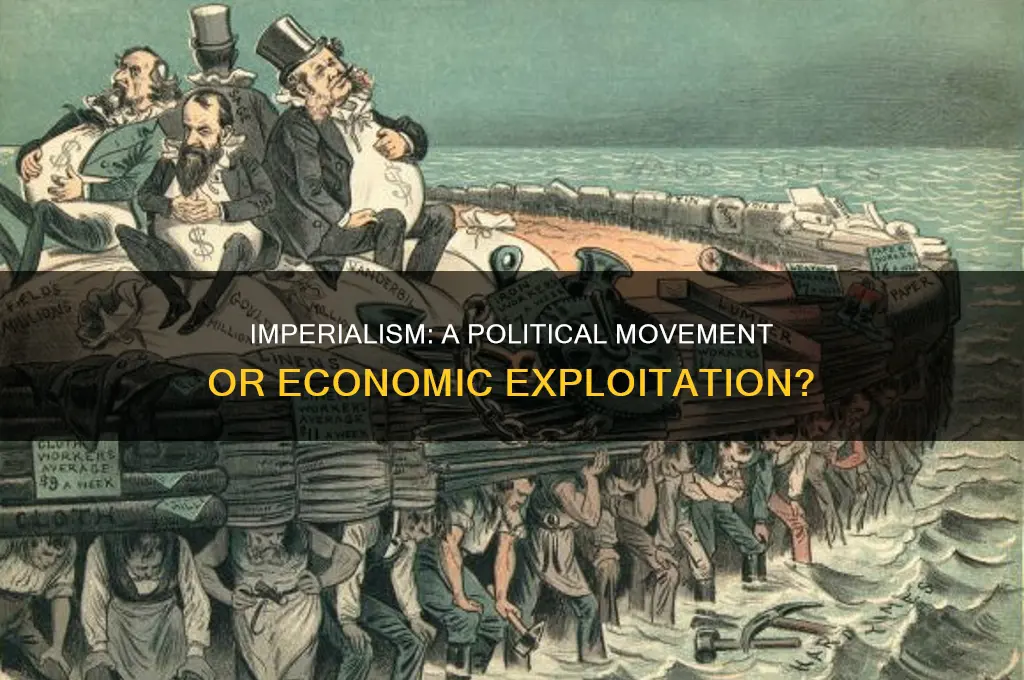

Imperialism, often characterized by the extension of a nation’s power through territorial acquisition, economic dominance, or cultural influence, raises the question of whether it can be classified as a political movement. At its core, imperialism is inherently political, as it involves the deliberate expansion of state authority and the imposition of one nation’s political systems, ideologies, and governance structures onto another. While it is driven by economic, military, and cultural motives, its execution is fundamentally a political endeavor, often justified through ideologies like national superiority, civilizing missions, or geopolitical necessity. Thus, imperialism can be viewed as a political movement in the sense that it is orchestrated by states or ruling elites to achieve specific political objectives, reshape global power dynamics, and assert dominance on the international stage.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Imperialism refers to the policy or practice of extending a country's power and influence through diplomacy or military force, often resulting in the establishment of colonies or dependencies. |

| Political Nature | Imperialism is inherently political as it involves the expansion of a state's political control over other territories, often driven by political ideologies, nationalistic ambitions, and the desire for global influence. |

| Economic Motivation | While economic factors (e.g., resource extraction, market expansion) play a significant role, the political movement aspect emphasizes the strategic and ideological goals of dominating and controlling other regions. |

| Military Expansion | Political imperialism often relies on military power to conquer, occupy, and administer territories, reinforcing political dominance. |

| Cultural and Ideological Control | Imperialist powers frequently impose their political systems, values, and ideologies on colonized peoples, aiming to reshape their political landscapes. |

| Colonial Administration | The establishment of political institutions and governance structures in colonies to maintain control and enforce the imperial power's political agenda. |

| Global Influence | Imperialism as a political movement seeks to project a nation's political power globally, often competing with other imperial powers for dominance. |

| Nationalism | Often fueled by nationalist sentiments, imperialism is used as a tool to enhance a nation's prestige and political standing on the world stage. |

| Resistance and Decolonization | The political nature of imperialism has led to resistance movements and eventual decolonization, as colonized peoples sought political autonomy and self-governance. |

| Legacy | The political movement of imperialism has left lasting impacts on global politics, including the formation of modern nation-states, international relations, and ongoing geopolitical tensions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Economic motivations behind imperial expansion

Imperialism, often viewed through the lens of political dominance, was fundamentally driven by economic ambitions. The pursuit of wealth, resources, and markets compelled nations to expand their territories, establishing a global network of exploitation. This economic imperative was not merely a byproduct of political ideology but a primary force shaping imperial policies and actions.

Consider the British Empire's colonization of India, a prime example of economic motivation. Britain sought to control India's vast resources, including textiles, spices, and raw materials, which fueled its industrial revolution. The East India Company, acting as both a commercial entity and an arm of the state, imposed heavy taxation and monopolized trade, siphoning wealth back to Britain. This economic drain, known as the "drain of wealth," illustrates how imperialism functioned as a system of extraction, prioritizing the metropole's prosperity over the colony's development.

Analyzing this pattern reveals a recurring strategy: imperial powers identified regions rich in resources or strategic trade locations and exploited them to sustain their economies. For instance, Belgium's brutal colonization of the Congo was driven by the demand for rubber and ivory. King Leopold II's regime forced Congolese laborers into harsh conditions, resulting in millions of deaths, to meet the global market's insatiable appetite for these commodities. This case underscores the ruthless economic logic of imperialism, where human lives were secondary to profit.

To understand the economic motivations further, examine the role of tariffs and trade policies. Imperial powers often imposed unequal trade agreements, ensuring their industries thrived while stifling local economies. For example, British policies in India prohibited the production of certain goods, forcing Indians to purchase British-made products. This dependency created a captive market, securing long-term economic benefits for the colonizer. Such practices highlight how imperialism was not just about territorial control but about restructuring global economies to favor the dominant power.

In conclusion, the economic motivations behind imperial expansion were multifaceted and relentless. From resource extraction to market domination, imperial powers employed a variety of strategies to enrich themselves at the expense of colonized peoples. Recognizing these economic drivers is crucial for understanding imperialism as a systemic phenomenon, not merely a political movement. It was, at its core, a calculated effort to reshape the global economy in favor of the powerful, leaving a legacy of inequality that persists to this day.

Understanding Political Cohesion: Unity, Stability, and Governance Explained

You may want to see also

Role of nationalism in imperialist policies

Nationalism served as a potent ideological fuel for imperialist policies, transforming expansionist ambitions into morally justified missions. By framing colonial ventures as extensions of a nation’s destiny or superiority, imperial powers mobilized domestic support and legitimized their actions abroad. For instance, 19th-century European nations like Britain and France invoked nationalist rhetoric to portray their empires as civilizing forces, spreading progress and enlightenment to "backward" peoples. This narrative not only masked economic exploitation but also fostered a sense of collective pride among citizens, making imperialism a politically palatable and even celebrated endeavor.

Consider the practical mechanics of this relationship: nationalist education systems glorified imperial achievements, while propaganda campaigns depicted colonies as integral to national greatness. In Germany, the late 19th-century *Drang nach Osten* (Drive to the East) was justified as a natural expansion of German culture and power. Similarly, Japan’s Meiji-era imperialism was framed as a restoration of national glory and a response to Western encroachment. These examples illustrate how nationalism provided a framework for imperialist policies, turning territorial aggression into a patriotic duty.

However, the interplay between nationalism and imperialism was not without tension. While nationalism unified populations behind imperial goals, it also sowed seeds of resistance in colonized regions. Indigenous peoples often responded by forging their own nationalist movements, challenging imperial dominance. For example, the Indian independence movement drew strength from anti-colonial nationalism, ultimately undermining British rule. This paradox reveals that while nationalism propelled imperialist policies, it also empowered those seeking to dismantle empires.

To understand the role of nationalism in imperialism, think of it as a double-edged sword. On one side, it provided the emotional and ideological glue that held imperial projects together, making them politically sustainable. On the other, it inspired counter-movements that questioned and eventually dismantled colonial structures. For modern policymakers or historians, this dynamic offers a cautionary tale: nationalism can be a powerful tool for mobilization, but its consequences are unpredictable and often self-defeating.

In conclusion, nationalism was not merely a byproduct of imperialism but a driving force that shaped its policies and outcomes. By examining its role, we gain insight into how political movements can both justify and undermine systems of power. Whether analyzing historical empires or contemporary geopolitics, the symbiotic relationship between nationalism and imperialism remains a critical lens for understanding the complexities of global domination and resistance.

Honoring Political Volunteers: Meaningful Ways to Show Gratitude and Appreciation

You may want to see also

Impact of imperialism on colonized societies

Imperialism, as a political movement, reshaped colonized societies in profound and often irreversible ways. One of its most immediate impacts was the economic exploitation of resources and labor. Colonial powers established systems like cash crop agriculture, mining, and plantations, which drained local economies of their wealth. For instance, in the Belgian Congo, rubber extraction under King Leopold II’s regime led to forced labor and the deaths of millions. This economic restructuring not only impoverished local populations but also created dependencies on colonial markets, stifling indigenous industries and trade networks.

Beyond economics, imperialism eroded cultural identities by imposing foreign values, languages, and institutions. Missionaries and colonial administrators often sought to replace traditional beliefs with Christianity, while Western education systems marginalized local knowledge. In India, British colonial policies undermined indigenous education systems, promoting English-medium schools that favored the elite. This cultural imposition fostered a sense of inferiority among colonized peoples, as their traditions were labeled "backward" or "uncivilized." The long-term effect was a generational disconnect from heritage, as younger populations struggled to reconcile colonial legacies with their cultural roots.

Politically, imperialism centralized power in the hands of colonial authorities, dismantling existing governance structures. Traditional leadership systems were either co-opted or abolished, replaced by bureaucratic administrations that prioritized colonial interests. For example, in Africa, the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 arbitrarily drew borders without regard for ethnic or cultural divisions, creating conflicts that persist today. This political reengineering not only disempowered local leaders but also sowed the seeds of instability, as post-colonial nations grappled with artificial boundaries and imposed identities.

Socially, imperialism created hierarchies that privileged colonizers and their collaborators while marginalizing the majority. Racial segregation, as seen in South Africa’s apartheid system, institutionalized discrimination and limited access to resources for indigenous populations. Even in colonies where overt segregation was less pronounced, social mobility was restricted by race and class. These divisions often persisted post-independence, shaping modern societal inequalities. For instance, in many former French colonies, the elite educated in French institutions continue to dominate political and economic spheres, perpetuating colonial-era power dynamics.

Finally, imperialism altered demographic landscapes through migration, urbanization, and health interventions. Colonial powers often imported labor from other regions, as seen in the Indian indentured laborers brought to the Caribbean. Urban centers grew rapidly as rural populations were displaced by cash crop economies, leading to overcrowded cities with inadequate infrastructure. While medical advancements like vaccination campaigns reduced certain diseases, they were often unevenly distributed, benefiting colonizers more than the colonized. These demographic shifts reshaped social structures, creating new challenges for post-colonial societies.

In conclusion, the impact of imperialism on colonized societies was multifaceted, leaving a legacy of economic dependency, cultural dislocation, political fragmentation, social inequality, and demographic transformation. Understanding these effects is crucial for addressing the ongoing challenges faced by former colonies today.

Understanding Political Radicalism: Origins, Impact, and Modern Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political ideologies driving imperial powers

Imperialism, as a historical phenomenon, was undeniably fueled by a complex interplay of political ideologies that justified expansion, exploitation, and domination. At its core, the drive for imperial power often stemmed from the belief in a nation’s inherent superiority, whether rooted in racial, cultural, or economic terms. For instance, the concept of the "civilizing mission" was a recurring theme in European imperialism during the 19th and early 20th centuries. This ideology posited that colonizing powers had a moral obligation to uplift "backward" societies, a rationale that masked economic exploitation and territorial ambition. Such beliefs were not merely abstract; they were institutionalized through policies, education systems, and propaganda, shaping public opinion and legitimizing imperial actions.

To understand the political ideologies driving imperial powers, consider the role of nationalism. Imperialism often served as an extension of a nation’s self-perceived destiny, as seen in the case of Wilhelmine Germany’s *Weltpolitik* or Britain’s "Rule Britannia" ethos. These ideologies framed imperial expansion as a natural and necessary step for national greatness, fostering domestic unity while projecting power abroad. Nationalism also intertwined with social Darwinism, a pseudo-scientific ideology that justified imperialism as the survival of the fittest on a global scale. This dangerous fusion of ideas not only fueled competition among imperial powers but also dehumanized colonized peoples, portraying them as inferior and expendable.

Another critical ideology was economic determinism, which framed imperialism as a logical response to capitalist needs. The pursuit of raw materials, new markets, and cheap labor became a driving force for powers like Belgium in the Congo or Britain in India. Marxist theorists, such as Vladimir Lenin, argued that imperialism was the highest stage of capitalism, where monopolies and financial institutions pushed governments to seek overseas territories. This perspective highlights how economic ideologies were not just byproducts of imperialism but active catalysts, shaping policies and justifying the brutal extraction of resources from colonized regions.

Religious ideologies also played a significant role, particularly in the early phases of imperialism. The Spanish and Portuguese empires, for example, were driven by the zeal of the Catholic Church’s *Reconquista* mentality, which sought to spread Christianity alongside territorial control. Similarly, the Protestant ethos of "manifest destiny" in the United States justified westward expansion and the subjugation of indigenous peoples. These religious frameworks provided a moral veneer to imperial ambitions, blending spiritual salvation with political and economic dominance.

In analyzing these ideologies, it becomes clear that imperialism was not a monolithic movement but a multifaceted one, shaped by the unique political, economic, and cultural contexts of each imperial power. To dismantle its legacy, one must critically examine these ideologies, recognizing how they were constructed to serve specific interests. For educators and policymakers, this means teaching imperialism not as a series of isolated events but as a product of interconnected ideas that continue to influence global power dynamics today. By understanding the political ideologies that drove imperial powers, we can better navigate the complexities of modern geopolitics and work toward a more equitable world.

Crafting Political Theory: Essential Steps for Clear and Impactful Analysis

You may want to see also

Resistance movements against imperial rule

Imperialism, as a political movement, inherently provoked resistance. From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, colonized peoples across Asia, Africa, and the Americas mobilized against foreign domination, employing diverse strategies shaped by local contexts. These resistance movements were not monolithic; they ranged from armed uprisings to cultural assertions, each reflecting the unique grievances and aspirations of the oppressed.

Consider the Indian independence movement, a multifaceted struggle against British rule. Led by figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, it blended nonviolent civil disobedience with mass mobilization. Gandhi’s Salt March in 1930, a 240-mile protest against the salt tax, exemplified this approach, galvanizing millions while exposing the moral bankruptcy of imperial authority. Similarly, the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952–1960) showcased armed resistance, with Kikuyu fighters employing guerrilla tactics against British forces. Though brutally suppressed, the movement accelerated decolonization, illustrating the power of violent resistance in dismantling imperial control.

Cultural and intellectual resistance also played a pivotal role. In Algeria, the FLN (National Liberation Front) not only waged a military campaign against France but also revived Arab and Berber identities, countering French assimilationist policies. Similarly, the Negritude movement in Francophone Africa, spearheaded by Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor, reclaimed African cultural heritage as a form of resistance against European cultural imperialism. These movements underscored the importance of identity and ideology in challenging imperial dominance.

Resistance was not confined to the colonized; it often drew global solidarity. The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, for instance, gained international support through boycotts, sanctions, and divestment campaigns. This external pressure, combined with internal resistance led by the ANC, ultimately dismantled the apartheid regime. Such examples highlight how resistance movements transcended borders, leveraging global networks to amplify their cause.

In analyzing these movements, a key takeaway emerges: resistance to imperialism was as diverse as imperialism itself. While some opted for nonviolence, others embraced armed struggle; some focused on political independence, while others prioritized cultural revival. This diversity reflects the complexity of imperial rule and the ingenuity of those who fought against it. Understanding these movements not only sheds light on the past but also offers lessons for contemporary struggles against oppression.

Communism: Economic System, Political Ideology, or Both?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Imperialism was indeed a political movement, as it involved the extension of a country’s power through territorial acquisition, economic dominance, and political control over other regions. It was driven by political ideologies, such as national superiority and the civilizing mission, and was often justified by political leaders to expand their influence and resources.

Political ideologies like nationalism, Social Darwinism, and the belief in a civilizing mission fueled imperialism. Governments and leaders used these ideologies to justify their actions, portraying imperial expansion as a moral or political duty to bring progress and order to "less developed" regions.

While direct political control was a hallmark of imperialism, it also took indirect forms, such as economic exploitation or cultural influence. Political control was often the ultimate goal, but imperial powers sometimes relied on puppet regimes or economic dependencies to maintain their dominance without direct rule.