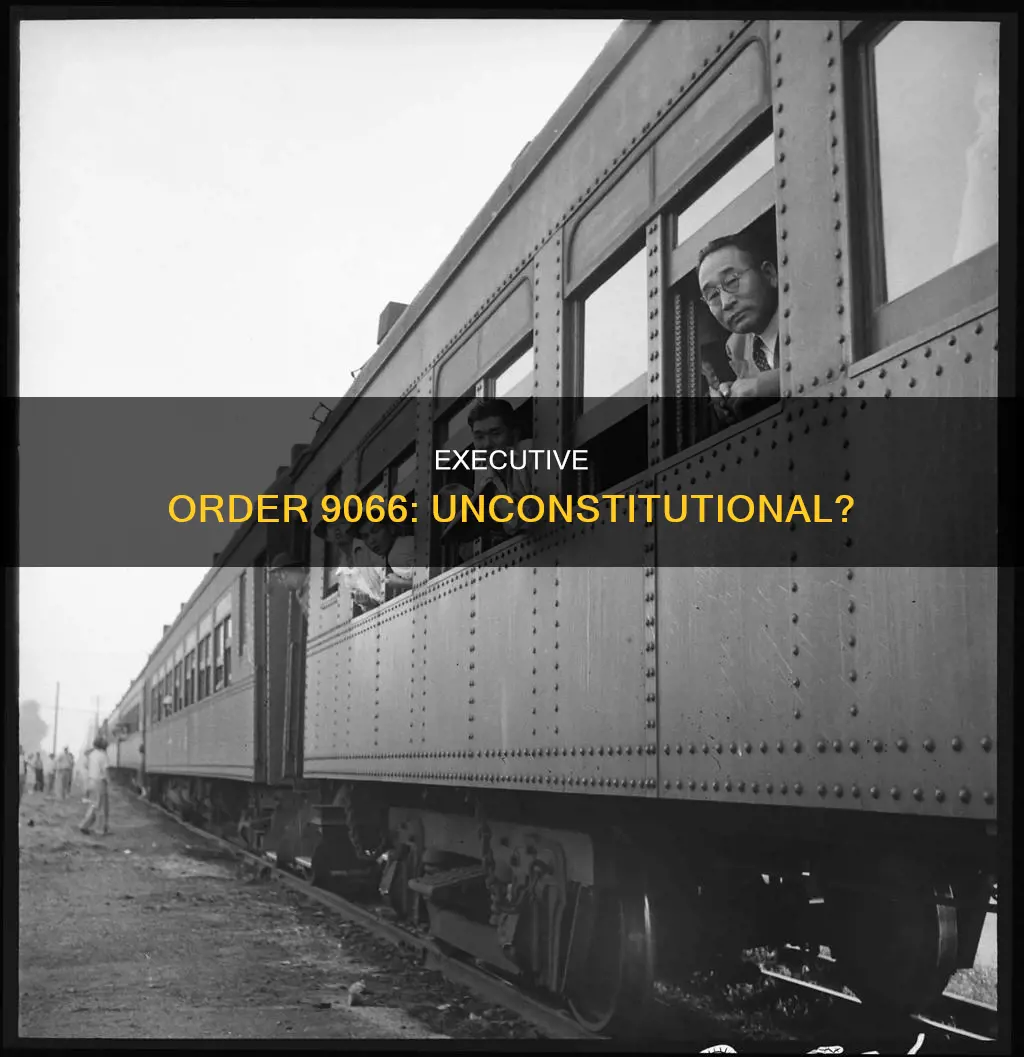

In response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The constitutionality of the order was challenged in the landmark Supreme Court case Korematsu v. United States in 1944, where the Court upheld the order as a necessary measure during wartime. However, the decision has been widely criticized and discredited for prioritizing national security over the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans. The case continues to spark debates about racial justice and the limits of executive power during times of crisis.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Order | February 19, 1942 |

| Issued by | President Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Impact | Forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes to military camps |

| Number of people impacted | 120,000-125,000 |

| Percentage of impacted population that was American citizens | Two-thirds |

| Legal challenges | Korematsu v. United States, Ex parte Mitsuye Endo |

| Ruling on Constitutionality | Ruled constitutional based on "military necessity" |

| Dissenting opinions | Justice Owen Roberts, Justice Frank Murphy, Justice Robert Jackson |

| Evidence of unconstitutionality | US Navy report stating Japanese Americans did not pose a threat |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The order was based on a false premise

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, was based on the false premise that Japanese Americans were "enemy aliens". This premise was disproven by crucial evidence discovered in 1983 by Peter Irons and Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga. The evidence, a copy of Lieutenant Commander K.D. Ringle's original report by the US Navy, revealed that Japanese Americans did not pose a threat to the US government, contrary to the assumptions underlying the order.

The order, which led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans, was not based on specific intelligence or evidence of disloyalty. Instead, it was a product of racial prejudice and xenophobia toward Asian Americans, stemming from Roosevelt's long-held racial views. The order was also influenced by the proximity of Japanese American communities to vital war assets along the Pacific Coast, raising unfounded fears of espionage and sabotage.

The false premise of Japanese Americans as "enemy aliens" was further challenged by Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American man who refused to comply with the order. Korematsu argued that the order violated the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, asserting that it targeted individuals based on their race rather than any hostile actions or disloyalty. Despite his appeal to the Supreme Court, the order was upheld in a 6-3 decision, with the Court justifying the order as a military necessity.

The dissenting opinions in the Korematsu case highlighted the racial discrimination inherent in the order. Justice Owen Roberts stated that the order exhibited a “clear violation of Constitutional rights," while Justice Frank Murphy described it as "the ugly abyss of racism," violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Justice Robert Jackson also emphasized that the order convicted individuals of "an act not commonly thought a crime," merely for their presence in their home state and proximity to their birthplace.

In conclusion, Executive Order 9066 was based on the false premise that Japanese Americans posed a threat as "enemy aliens." This premise was disproven by evidence and challenged by individuals like Korematsu, who exposed the racial discrimination and violation of constitutional rights inherent in the order. Despite these objections, the order resulted in the incarceration of over 100,000 Japanese Americans, highlighting the dangerous consequences of acting on false premises and ignoring constitutional protections.

Ethical Influence: Constitution's Role in Personal Codes

You may want to see also

It violated the Fifth Amendment

Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, authorized the forced removal and detention of all persons deemed a threat to national security, specifically targeting Japanese Americans. This order led to the incarceration of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans in relocation centers or internment camps, with two-thirds of those interned being U.S. citizens.

Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American man, refused to comply with the order and challenged its constitutionality. He argued that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which protects individuals from being deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Korematsu's case, known as Korematsu v. United States, was heard by the Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled in a 6-3 decision that the order was a "military necessity."

Korematsu's refusal to obey the order resulted in his arrest and conviction for violating military orders. He argued that the order violated his constitutional rights, as it deprived him of his liberty and property without due process solely based on his race. However, the Supreme Court's decision, written by Justice Hugo Black, asserted that the need to protect against espionage by Japan outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry.

The dissenting opinions in the Korematsu case strongly criticized the majority's decision. Justice Robert Jackson highlighted the unprecedented nature of convicting an individual for "an act not commonly thought a crime," such as residing in their state of citizenship. He and Justice Frank Murphy argued that the nation's security concerns did not justify stripping Korematsu and the other internees of their constitutionally protected civil rights, with Murphy specifically calling out the "legalization of racism" and the violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In conclusion, the argument that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment centers on the infringement of Japanese Americans' constitutional rights to liberty and property. The order resulted in their forced removal from their homes and incarceration without due process, solely based on their race and ancestry. While the Supreme Court upheld the order as a military necessity, the dissenting opinions emphasized the racial discrimination and civil rights violations inherent in the decision.

Texas Constitution: Foundation for a Sovereign State

You may want to see also

It was a form of legalised racism

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, was a form of legalised racism. The order, which was enacted during World War II, authorised the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centres" further inland, resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. While the order did not specifically mention Japanese Americans, it was quickly applied to the majority of the Japanese American population on the West Coast, with over 100,000 people detained and moved to camps in the following six months.

The order was consistent with Roosevelt's long-held racial views towards Japanese Americans. During the 1920s, Roosevelt wrote articles opposing interracial marriage between whites and Japanese, citing concerns about the "mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood." This demonstrates that Roosevelt's decision to sign the order was influenced by his racist beliefs.

The implementation of the order further reinforces the notion of legalised racism. Japanese Americans were not allowed to apply for citizenship, and they faced strict travel bans and xenophobia. They were labelled as "alien enemies," despite many being U.S. citizens or long-term residents. The order resulted in the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, with two-thirds of the 125,000 people displaced being U.S. citizens.

The constitutionality of the order was challenged in the case of Korematsu v. United States, where Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese American, refused to comply with the relocation order. Korematsu argued that the order violated the Fifth Amendment, but the Supreme Court ruled in a 6-3 decision that the detention was a "military necessity" and not based on race. However, the dissenting justices strongly criticised the order as legalised racism, highlighting that it violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans and perpetuated racial discrimination.

In conclusion, Executive Order 9066 represented a form of legalised racism. It was rooted in Roosevelt's racist ideologies and resulted in the discriminatory treatment and incarceration of Japanese Americans. While the Supreme Court upheld the order, dissenting justices exposed the racism inherent in the decision, underscoring the violation of constitutional rights and the ugly reality of racial discrimination.

Constitutional Revisions: 1992's Amendments Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$71.95 $71.95

It was a necessary military decision

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. The order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to relocation centers further inland, resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. The Supreme Court upheld the order on the grounds of "military necessity".

The argument for the necessity of Executive Order 9066 from a military perspective was based on several factors. Firstly, the order was issued in the context of World War II, specifically following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This attack heightened fears and concerns about the safety of America's West Coast, where a significant number of Japanese Americans resided. The proximity of these individuals to vital war assets and infrastructure was considered a potential security risk.

Secondly, the order was justified as a preventive measure against espionage and sabotage. Justice Hugo Black, who wrote the majority opinion in the Korematsu v. United States case, stated that the need to protect against espionage by Japan outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry. He argued that Korematsu was excluded from the Military Area not because of racial hostility but due to the military urgency of ensuring the West Coast's security.

Additionally, the order was presented as a temporary measure during a time of war. Justice Black further denied that the case had anything to do with racial prejudice, stating that the decision was based on the need to protect against potential invasion and espionage. The military argued that the urgency of the situation demanded the segregation of citizens of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast until the threat could be mitigated.

Furthermore, the order was consistent with Roosevelt's long-held racial views toward Japanese Americans. Roosevelt had previously expressed opposition to white-Japanese intermarriage and supported bans on land ownership by first-generation Japanese Americans. These views likely influenced his decision-making during World War II, contributing to the perception of Japanese Americans as a potential threat to national security.

While the order resulted in the incarceration of over 100,000 Japanese Americans, with two-thirds of them being U.S. citizens, the military argued that it was a necessary precaution to ensure the safety of the nation during a time of war. The Supreme Court's decision to uphold the order on the grounds of "military necessity" reflects the prioritization of national security over individual rights during this tumultuous period in American history.

Constitutions Shaping New York's History and Future

You may want to see also

It was upheld by the Supreme Court

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. The order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland, resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans. The order was based on the false premise that Japanese Americans were "enemy aliens" and posed a threat to national security.

Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese-American man, refused to comply with the order and challenged its constitutionality. He argued that the order violated the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which protects against the deprivation of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Korematsu was arrested and convicted, and his case eventually reached the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, upheld the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 on the grounds of "military necessity." The Court found that the need to protect against espionage and sabotage outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Justice Hugo Black, who wrote the majority opinion, denied that the case had anything to do with racial prejudice and asserted that the decision was based on the uncertainty following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The dissenting opinions in the Supreme Court's decision strongly criticized the racial implications of the order. Justice Robert Jackson argued that the order legalized racism and violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans. He highlighted the fact that Japanese Americans were being convicted of an act not commonly considered a crime, simply for being present in the state where they were citizens. Another dissenting Justice, Frank Murphy, agreed that the order constituted "the legalization of racism" and violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In conclusion, the Supreme Court's decision to uphold Executive Order 9066 set a precedent for racial discrimination in criminal procedure and the relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II. While the Court justified its decision based on military necessity, the dissenting opinions highlighted the racial injustice and constitutional violations inherent in the order.

Federal Democratic Republic: Constitution's Vision?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Executive Order 9066 was an order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese military forces. The order allowed the U.S. military to relocate individuals of Japanese ancestry to designated areas and imposed curfews on them.

Fred Korematsu, a 22-year-old Japanese-American, refused to leave his residence in California and challenged the order on the grounds that it violated the Fifth Amendment. The Supreme Court affirmed Korematsu's conviction, with Justice Hugo Black stating that the need to protect against espionage outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry.

The constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 is a highly debated topic. The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union)'s national executive director, Roger Baldwin, argued that the order deprived American citizens of their liberty and property without due process, violating the Fifth Amendment. However, the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States upheld the order as constitutional, citing military necessity and protection against espionage. The decision has since been criticized and repudiated, with Congress passing the Civil Liberties Act in 1988 to offer reparations and a formal apology.