Bob Dylan, a towering figure in the world of music and culture, has long been associated with political themes and social commentary throughout his career. From his early folk songs in the 1960s, such as Blowin' in the Wind and The Times They Are A-Changin', to his later works, Dylan's lyrics often addressed issues like civil rights, war, and economic inequality. While he has never explicitly aligned himself with a particular political party or ideology, his music has consistently reflected a deep engagement with the political and social upheavals of his time. Dylan's role as a voice of dissent and a chronicler of societal change has sparked ongoing debates about the extent of his political involvement and the impact of his art on public consciousness.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Involvement | Bob Dylan has been politically active, particularly during the 1960s, addressing civil rights, anti-war movements, and social justice in his music. |

| Iconic Protest Songs | Wrote and performed influential protest songs like "Blowin' in the Wind," "The Times They Are a-Changin'," and "Masters of War." |

| Civil Rights Movement | Supported the Civil Rights Movement, performing at the March on Washington in 1963. |

| Anti-War Stance | Voiced strong opposition to the Vietnam War through his music and public statements. |

| Ambiguity in Later Years | Became less overtly political in his later career, focusing more on personal and poetic themes. |

| Influence on Activism | His early work inspired and mobilized activists during the 1960s counterculture movement. |

| Awards and Recognition | Received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, partly for his impact on political and social discourse through music. |

| Political Commentary | Continued to address political themes subtly in his later albums, though less directly than in his early career. |

| Cultural Impact | Remains a symbol of political and social activism in American culture. |

| Personal Politics | Generally identified with liberal and progressive causes, though he has avoided explicit political endorsements. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dylan's Protest Songs: Early 1960s folk anthems like Blowin' in the Wind addressed civil rights, war

- Anti-War Activism: Vocal opposition to Vietnam War through music and public statements

- Civil Rights Support: Performed at marches, wrote songs supporting racial equality

- Criticism of Authority: Lyrics often challenged government, societal norms, and power structures

- Later Political Ambiguity: Shifted focus, became less overtly political in later career

Dylan's Protest Songs: Early 1960s folk anthems like Blowin' in the Wind addressed civil rights, war

Bob Dylan's early 1960s protest songs, particularly "Blowin' in the Wind," became anthems for a generation grappling with civil rights and the specter of war. Released in 1963, the song's deceptively simple lyrics—"How many times must a man look up / Before they can see the sky?"—posed profound questions about injustice and moral responsibility. Dylan's use of rhetorical queries, coupled with a haunting melody, transformed the track into a universal call for change, resonating far beyond the folk revival movement.

Analyzing "Blowin' in the Wind" reveals Dylan's strategic blending of poetic ambiguity and political urgency. Unlike explicit political slogans, the song's open-ended nature allowed listeners to project their own struggles onto its verses. For civil rights activists, it spoke to racial inequality; for anti-war protesters, it questioned the Vietnam War's morality. This adaptability amplified its impact, making it a rallying cry across diverse causes. Dylan's role here wasn't merely as a songwriter but as a catalyst for collective introspection.

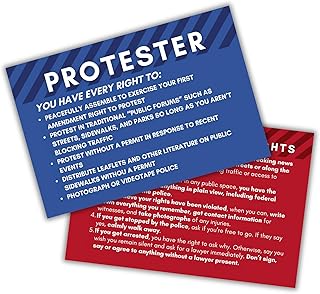

To understand the song's reach, consider its practical application in protests. Activists often sang "Blowin' in the Wind" at marches, using its repetitive chorus to unify voices and amplify their message. For organizers, the song served as a non-confrontational yet powerful tool, bridging ideological divides within movements. Even today, educators teaching civil rights history frequently use the song to illustrate the era's emotional and intellectual climate, proving its enduring relevance.

Comparatively, while other protest songs of the era were more direct—such as Phil Ochs' "I Ain't Marching Anymore"—Dylan's approach was subtler yet equally potent. His ability to weave personal and political themes without alienating audiences set a precedent for politically engaged art. This balance between accessibility and depth remains a lesson for modern artists seeking to address societal issues without sacrificing artistic integrity.

In conclusion, Dylan's protest songs, epitomized by "Blowin' in the Wind," were more than musical statements; they were actionable tools for social change. By framing political questions as universal human dilemmas, Dylan created a blueprint for art that challenges without preaching. For anyone studying the intersection of music and politics, these early works offer invaluable insights into how creativity can drive cultural and political movements.

Do Facts Matter in Politics? Exploring Truth's Role in Modern Governance

You may want to see also

Anti-War Activism: Vocal opposition to Vietnam War through music and public statements

Bob Dylan's anti-war activism during the Vietnam War era was not just a phase; it was a pivotal chapter in his career that cemented his role as a voice of dissent. Through his music and public statements, Dylan articulated the growing unease and moral outrage of a generation. His song *"Blowin' in the Wind"* (1963) became an anthem for the anti-war movement, posing existential questions about peace, war, and freedom that resonated deeply with those protesting the conflict. Dylan’s lyrics were not explicit calls to action but rather thought-provoking inquiries that encouraged listeners to question the status quo.

To understand Dylan’s impact, consider the strategic use of his platform. He didn’t just write songs; he performed them at rallies, festivals, and concerts, amplifying his message to diverse audiences. For instance, his appearance at the 1963 March on Washington, where he performed alongside civil rights leaders, demonstrated his commitment to aligning music with political activism. Dylan’s public statements, though infrequent, carried weight. In a 1964 interview, he famously quipped, *"I don’t consider myself a spokesman for anybody,"* yet his actions and art spoke volumes for those opposed to the war.

A practical takeaway for modern activists is the power of subtlety in messaging. Dylan’s anti-war songs often avoided direct confrontation, opting instead for allegory and metaphor. This approach allowed his music to transcend specific political moments, making it timeless. For example, *"Masters of War"* (1963) criticizes war profiteers and political leaders without naming them, ensuring its relevance across conflicts. Activists today can emulate this by crafting messages that resonate universally, rather than focusing solely on immediate issues.

Comparatively, Dylan’s anti-war activism stands out from other artists of his time due to its intellectual depth and refusal to be co-opted by any single movement. While artists like Joan Baez and Pete Seeger were more overtly political, Dylan’s work maintained a critical distance, challenging listeners to think rather than simply react. This nuanced approach made his opposition to the Vietnam War more than a protest—it was a cultural reckoning. By studying Dylan’s methods, activists can learn the value of engaging audiences on an emotional and intellectual level, fostering lasting change rather than fleeting outrage.

Understanding Political Aims: Goals, Strategies, and Societal Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Civil Rights Support: Performed at marches, wrote songs supporting racial equality

Bob Dylan's involvement in the Civil Rights Movement was not merely symbolic; it was active and impactful. One of the most tangible ways he supported racial equality was by performing at key marches and rallies. For instance, in 1963, Dylan took the stage at the historic March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech. Dylan’s presence and performance of songs like "When the Ship Comes In" underscored his commitment to the cause, using his platform to amplify the movement’s message. This act of solidarity was more than a performance—it was a declaration of his alignment with the struggle for justice.

Dylan’s songwriting further cemented his role as a voice for civil rights. Songs like "Blowin’ in the Wind" and "The Times They Are A-Changin’" became anthems for activists, their lyrics questioning societal norms and calling for equality. These songs were not just artistic expressions but tools for mobilization, resonating deeply with those fighting against racial injustice. By weaving political themes into his music, Dylan ensured that his art served a purpose beyond entertainment, becoming a catalyst for dialogue and change.

To understand Dylan’s impact, consider the practical ways his music was used. Activists often sang his songs during protests, using them as a unifying force. For example, "We Shall Overcome" was frequently paired with Dylan’s work in rallies, creating a soundtrack for the movement. If you’re organizing a modern protest or educational event, incorporating such songs can evoke historical solidarity and inspire participants. Pairing music with speeches or workshops can deepen engagement, much like Dylan’s performances did in the 1960s.

However, Dylan’s involvement was not without complexity. While he supported racial equality, his approach was often introspective rather than overtly confrontational. This nuance is important for anyone studying his political legacy. For educators or activists, using Dylan’s music as a teaching tool requires context—explaining his role in the movement alongside its broader history ensures a comprehensive understanding. Pair his songs with primary sources like speeches or news articles from the era to provide a fuller picture.

In conclusion, Dylan’s civil rights support through performances and songwriting remains a powerful example of art intersecting with activism. His actions demonstrate how artists can contribute to social movements in meaningful ways. Whether you’re an educator, activist, or enthusiast, exploring this aspect of Dylan’s career offers valuable insights into the role of music in political change. By studying his methods and impact, we can draw lessons for contemporary struggles, ensuring that art continues to serve as a force for justice.

Mastering Political Photography: Tips for Capturing Powerful, Impactful Images

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Criticism of Authority: Lyrics often challenged government, societal norms, and power structures

Bob Dylan's lyrics have long served as a battleground for the critique of authority, dismantling the facades of government, societal norms, and power structures with surgical precision. Songs like *"The Times They Are A-Changin'"* and *"Blowin' in the Wind"* didn't merely question the status quo—they demanded accountability. Dylan's pen acted as a mirror, reflecting the hypocrisy of those in power while amplifying the voices of the marginalized. His work wasn't just music; it was a call to action, urging listeners to scrutinize the systems that governed their lives.

Consider the instructive nature of *"Masters of War,"* a scathing indictment of the military-industrial complex. Dylan doesn't mince words, addressing the "masters" directly: *"You that build all the guns / You that build the death planes / You that build the big bombs."* This isn't abstract criticism—it’s a step-by-step dismantling of the profiteers of war. The song serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us that unchecked power corrupts, and those who wield it must be held to account. For activists or educators, this track is a primer on how art can expose systemic injustice.

Dylan's persuasive power lies in his ability to weave personal narratives into broader critiques. *"Hurricane,"* for instance, isn't just a story about Rubin Carter—it’s a condemnation of racial bias in the justice system. By humanizing the victim, Dylan forces listeners to confront their own complicity in perpetuating societal norms that allow such injustices. This approach is particularly effective because it doesn’t preach; it invites empathy, making the critique of authority feel personal rather than political.

Comparatively, while other artists of the 1960s addressed similar themes, Dylan’s work stands out for its specificity and relentlessness. Unlike the more abstract protests of some contemporaries, Dylan’s lyrics often named names and pointed fingers. *"Only a Pawn in Their Game,"* for example, explicitly ties the assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers to systemic racism, leaving no room for ambiguity. This directness made his music a lightning rod for both admiration and backlash, proving that true criticism of authority requires courage.

In practical terms, Dylan’s approach offers a blueprint for modern artists and activists. His songs demonstrate that critique doesn’t have to be overt to be effective—it can be embedded in storytelling, metaphor, or even folk melodies. For those looking to challenge authority today, the takeaway is clear: specificity matters. Whether you’re writing a song, crafting a speech, or designing a campaign, identify the power structures you’re targeting and dissect them with precision. Dylan’s legacy reminds us that art isn’t just a reflection of society—it’s a tool to reshape it.

Ajaz Khan's Political Entry: Rumors, Reality, and Future Speculations

You may want to see also

Later Political Ambiguity: Shifted focus, became less overtly political in later career

Bob Dylan's later career presents a fascinating paradox: the once-unapologetic protest singer, whose lyrics fueled civil rights anthems like "Blowin' in the Wind" and "The Times They Are A-Changin'," gradually retreated from overt political statements. This shift, noticeable from the 1970s onwards, wasn't a complete abandonment of social commentary, but rather a move towards subtlety and ambiguity. His 1983 album *Infidels*, for instance, contains "License to Kill," a song critiquing environmental destruction and societal apathy, but its message is woven into poetic imagery rather than direct calls to action.

Dylan's evolving approach raises questions about the role of the artist in political discourse. Does the artist have a responsibility to remain a vocal advocate, or is there value in allowing listeners to interpret and apply messages to their own contexts? Dylan's later work suggests a belief in the latter. Songs like "Everything is Broken" (1989) paint a bleak picture of societal decay without offering clear solutions, leaving listeners to grapple with the implications.

This ambiguity doesn't signify apathy. Dylan's 2020 album *Rough and Rowdy Ways* includes "Murder Most Foul," a sprawling epic dissecting the assassination of John F. Kennedy and its cultural impact. While not a traditional protest song, it's a powerful commentary on historical trauma and the enduring legacy of violence. Dylan's later political engagement is less about rallying cries and more about prompting reflection and critical thinking.

Instead of viewing this shift as a retreat, we can see it as a maturation of his artistic voice. Dylan's early songs were necessary for their time, providing anthems for a generation seeking change. His later work, with its layered meanings and open-ended questions, challenges listeners to engage more deeply with the complexities of the world.

Understanding Dylan's later political ambiguity requires a shift in perspective. It's not about finding clear-cut answers, but about embracing the power of art to provoke thought, spark dialogue, and inspire individual interpretation. His music continues to be politically relevant, not through overt slogans, but through its ability to capture the enduring struggles and uncertainties of the human condition.

Unveiling Political Collusion: Secret Alliances and Their Impact on Democracy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Bob Dylan was actively involved in politics, particularly during the 1960s. His music often addressed social and political issues, and he participated in civil rights and anti-war movements.

Absolutely. Many of Dylan's songs, such as "Blowin' in the Wind," "The Times They Are a-Changin'," and "Masters of War," directly address political and social issues, becoming anthems for activism.

Dylan was not formally affiliated with any political party, but his music and activism aligned with progressive and leftist causes, particularly during the 1960s. Later in his career, his views became more nuanced and less overtly political.

Yes, Dylan's political views evolved. While he was deeply engaged with activism in the 1960s, his later work became more introspective and less overtly political. He has often avoided being labeled or confined to a specific ideology.