The question of whether political parties should receive state funding is a contentious issue that sparks debate across the political spectrum. Proponents argue that public financing can level the playing field, reduce the influence of private donors, and promote democratic participation by ensuring that all parties, regardless of their financial backing, have the resources to compete fairly. They contend that this approach fosters transparency and diminishes the risk of corruption or undue influence from wealthy individuals or corporations. Conversely, critics assert that state funding could lead to taxpayer money being allocated to parties with ideologies they oppose, potentially stifling grassroots movements and independent candidates. Additionally, they argue that it might create a dependency on public funds, discouraging parties from engaging with their supporters and raising funds through traditional means. This debate raises fundamental questions about the role of government in shaping political landscapes and the balance between equity and individual choice in democratic systems.

Explore related products

$192 $66.99

What You'll Learn

- Fairness in Funding: Ensures equal resources for all parties, reducing financial disparities and promoting democratic equity

- Accountability Measures: State funding requires transparency, accountability, and strict oversight to prevent misuse of public funds

- Impact on Corruption: Reduces reliance on private donors, potentially lowering corruption and undue influence in politics

- Voter Engagement: State funding may level the playing field, encouraging smaller parties and diverse voter representation

- Taxpayer Burden: Raises concerns about using public funds for political activities, impacting taxpayer priorities

Fairness in Funding: Ensures equal resources for all parties, reducing financial disparities and promoting democratic equity

Financial disparities among political parties can distort democratic processes, giving wealthier groups disproportionate influence over policy and public discourse. State funding, when structured to provide equal resources to all parties, directly addresses this imbalance. For instance, in Germany, state funding is allocated based on a party’s electoral performance, ensuring smaller parties receive sufficient resources to compete. This model demonstrates how public financing can level the playing field, allowing diverse voices to participate meaningfully in elections. Without such mechanisms, democracies risk becoming oligopolies of the wealthy, where financial might, not popular will, drives political outcomes.

Implementing state funding requires careful design to avoid unintended consequences. A tiered system, where funding scales with a party’s voter base or membership, can prevent misuse by fringe or inactive groups. For example, Sweden ties state funding to a party’s share of the national vote, ensuring resources reflect public support. Additionally, transparency measures, such as mandatory financial reporting, can hold parties accountable for how funds are spent. Critics argue this system could burden taxpayers, but the cost is minimal compared to the benefits of a more equitable democracy. A 2020 study by the International Institute for Democracy found that countries with state funding saw a 25% increase in voter turnout, as citizens felt their choices were genuinely representative.

One common objection to state funding is the potential for taxpayer money to support parties with extremist or unpopular agendas. However, this concern can be mitigated by setting eligibility criteria, such as requiring parties to secure a minimum percentage of the vote or demonstrate a broad membership base. For instance, Norway mandates that parties must win at least 1.5% of the national vote to qualify for state funding. This approach ensures resources are directed toward parties with demonstrable public support while still fostering inclusivity. It strikes a balance between fairness and fiscal responsibility, preserving the integrity of the democratic process.

Ultimately, state funding of political parties is not just about money—it’s about restoring trust in democracy. When citizens see that all parties, regardless of size or wealth, have the resources to engage in fair competition, they are more likely to participate in the political process. This principle is particularly vital in emerging democracies, where financial disparities often stifle new or minority voices. By adopting state funding, nations can move closer to the ideal of "one person, one vote," where influence is determined by ideas and public support, not financial backing. The goal is not to eliminate competition but to ensure it is fair, transparent, and reflective of the collective will.

Unveiling the Origins: Who Created the Political Compass?

You may want to see also

Accountability Measures: State funding requires transparency, accountability, and strict oversight to prevent misuse of public funds

Public funding for political parties is a double-edged sword. While it can level the playing field and reduce reliance on private donors, it also risks becoming a slush fund without robust accountability measures. Taxpayer money demands transparency, not just in how funds are allocated, but in how they are spent. Every penny must be traceable, from campaign materials to staff salaries, with detailed reports accessible to the public. This isn't about distrusting parties, but about upholding the integrity of the democratic process.

Consider Germany's model, where state funding is tied to a party's electoral performance and membership numbers. This incentivizes parties to engage with citizens and build genuine support, rather than relying solely on financial backing from special interests. However, even this system requires stringent oversight. Independent audit bodies, free from political influence, must scrutinize party finances regularly. Penalties for misuse, such as fines or funding cuts, should be severe enough to deter wrongdoing but fair enough to avoid crippling legitimate operations.

Implementing such oversight isn't just about rules; it's about culture. Political parties must embrace a mindset of openness, viewing transparency as a duty rather than a burden. This could involve mandatory training for party officials on financial management and ethics, as well as public awareness campaigns to educate citizens on their right to demand accountability. Technology can also play a role, with blockchain-based systems offering an immutable record of transactions that even the most determined manipulator would struggle to alter.

Yet, accountability isn't solely the responsibility of parties or regulators. Citizens must be active participants, not passive observers. Tools like freedom of information requests and public forums should be utilized to hold parties to account. In countries like Sweden, where state funding is substantial, citizens can access detailed party expenditure reports online, fostering a culture of trust and engagement. This two-way street ensures that public funds serve the public interest, not private agendas.

Ultimately, state funding of political parties can be a force for good, but only if it comes with ironclad accountability measures. Transparency, oversight, and citizen involvement are not optional extras—they are the pillars that prevent misuse and ensure democracy thrives. Without them, public funding risks becoming a subsidy for opacity, undermining the very principles it seeks to uphold.

Which Political Party Truly Serves the People's Interests?

You may want to see also

Impact on Corruption: Reduces reliance on private donors, potentially lowering corruption and undue influence in politics

One of the most compelling arguments for state funding of political parties is its potential to curb corruption by reducing reliance on private donors. In systems where parties depend heavily on corporate or individual contributions, there’s an inherent risk that donors expect favors in return—be it favorable legislation, regulatory leniency, or government contracts. For instance, in the United States, where campaign financing is largely private, studies have shown a direct correlation between corporate donations and policy outcomes that benefit those donors. State funding, by contrast, could sever this quid pro quo dynamic, ensuring that parties are accountable to the public rather than to wealthy benefactors.

Consider the German model, where political parties receive state funding based on their electoral performance and membership dues. This system has been credited with minimizing corruption by limiting the influence of private donors. Parties are less likely to compromise their principles or policy positions when their financial survival doesn’t hinge on pleasing a small group of financiers. However, this approach isn’t without its challenges. Critics argue that state funding could lead to complacency among parties, reducing their incentive to engage with voters or innovate. To mitigate this, funding could be tied to transparency measures, such as mandatory disclosure of all expenditures and regular audits.

A step-by-step implementation of state funding could begin with capping private donations to political parties, say at 20% of their total budget, while gradually increasing public funding over a five-year period. This phased approach would allow parties to adapt without immediate financial shock. Additionally, public funding could be conditioned on parties meeting certain ethical standards, such as refusing donations from industries prone to corruption, like arms manufacturers or fossil fuel companies. Such safeguards would ensure that state funding doesn’t become a blank check but a tool for fostering integrity.

The comparative analysis of countries with and without state funding reveals a striking pattern. In nations like Sweden and Norway, where public funding is substantial, corruption levels are consistently lower, and public trust in political institutions is higher. Conversely, in countries like India, where private funding dominates, corruption scandals frequently dominate headlines. While state funding isn’t a panacea—it must be paired with robust anti-corruption laws and enforcement—it’s a critical step toward reducing undue influence in politics. The takeaway is clear: by shifting the financial burden from private donors to the state, we can create a political landscape that prioritizes the public good over private interests.

Herbert Hoover's Political Spectrum: Conservative, Progressive, or Centrist?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$37.11 $52

$24.93 $24.99

Voter Engagement: State funding may level the playing field, encouraging smaller parties and diverse voter representation

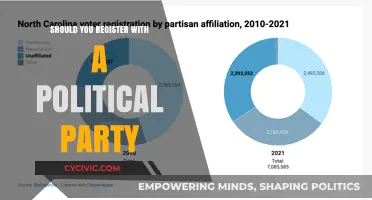

State funding for political parties has the potential to revolutionize voter engagement by addressing a fundamental imbalance in modern democracies: the dominance of well-funded, established parties. In many systems, smaller parties struggle to gain traction due to limited financial resources, which restricts their ability to campaign effectively, reach voters, and compete in elections. This financial barrier often results in a lack of diverse representation, as voters are left with few meaningful choices beyond the major parties. By allocating public funds to parties based on criteria such as vote share or membership, state funding can provide smaller parties with the resources needed to amplify their voices, engage with voters, and challenge the status quo.

Consider the case of Germany, where state funding for political parties is tied to their electoral performance. This system has allowed smaller parties like the Greens and the Left to grow from niche movements into significant political forces. In the 2021 federal election, these parties collectively secured over 20% of the vote, demonstrating how state funding can foster a more pluralistic political landscape. Such an approach not only levels the playing field but also encourages parties to focus on grassroots engagement and policy innovation rather than solely on fundraising. For instance, state funding could enable a small environmental party to run targeted campaigns in local communities, mobilizing voters who feel ignored by mainstream parties.

However, implementing state funding requires careful design to avoid unintended consequences. One concern is that unconditional funding might lead to complacency among parties, reducing their incentive to connect with voters. To mitigate this, funding could be tied to specific engagement metrics, such as voter turnout in party primaries or the diversity of party membership. For example, a party might receive additional funds for every 1,000 new members from underrepresented demographics, such as young adults (aged 18–25) or minority groups. This approach would not only ensure accountability but also align party interests with broader democratic goals.

Critics argue that state funding could alienate voters who oppose their tax dollars supporting parties they disagree with. To address this, transparency is key. Governments could create public dashboards detailing how funds are allocated and spent, allowing voters to see the impact of their contributions. Additionally, funding could be opt-in, with taxpayers given the choice to allocate a portion of their taxes to a specific party or a general fund. This model, similar to systems used in countries like Norway, empowers voters while maintaining the benefits of state funding.

Ultimately, state funding for political parties is not a panacea for low voter engagement, but it is a powerful tool for democratizing political participation. By reducing financial barriers, it can enable smaller parties to compete more effectively, offering voters a wider range of choices and perspectives. For democracies struggling with declining turnout and political apathy, this approach could reignite public interest in politics. Imagine a system where a local community-focused party, previously unable to afford campaign materials, uses state funds to organize town hall meetings and digital outreach, engaging voters who have long felt disconnected. Such scenarios illustrate how state funding can transform voter engagement from a passive act into an active, inclusive process.

Ending the Divide: Can Political Polarization Ever Truly Cease?

You may want to see also

Taxpayer Burden: Raises concerns about using public funds for political activities, impacting taxpayer priorities

Public funding of political parties inherently redirects taxpayer money from universally agreed-upon services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure to partisan activities. This allocation raises ethical questions about whether citizens should subsidize political agendas they may fundamentally oppose. For instance, a taxpayer who prioritizes environmental policies might resent their money funding a party advocating for fossil fuel expansion. This misalignment between individual values and state-funded priorities creates a moral dilemma at the heart of the taxpayer burden debate.

Consider the practical implications: in countries like Germany, state funding for parties is tied to election results, with each vote translating into a fixed monetary amount. While this system aims for fairness, it still means a portion of every taxpayer’s contribution is funneled into political machinery, regardless of their personal affiliations. In contrast, the U.S. relies on private donations, leaving taxpayers free from direct financial involvement in party politics but opening the door to corporate influence. Neither model is without flaws, but the former undeniably imposes a direct financial burden on citizens, warranting scrutiny.

Proponents argue that state funding reduces corruption by minimizing reliance on private donors. However, this trade-off often overlooks the opportunity cost: funds allocated to political parties are funds not allocated to public schools, hospitals, or social welfare programs. For example, in Sweden, where parties receive substantial state funding, critics point out that the equivalent of millions of dollars annually could instead fund hundreds of teacher salaries or improve public transportation. Taxpayers, already stretched by rising living costs, may view such allocations as a misplacement of priorities.

To mitigate taxpayer burden, some countries implement strict conditions on state funding. In Canada, parties must repay a portion of their funding if they fail to meet transparency or accountability standards. Such safeguards aim to ensure taxpayer money is used responsibly, but they do not eliminate the underlying concern: why should public funds be used for political activities at all? A more radical solution might involve creating a voluntary "political funding tax," allowing citizens to opt in or out of contributing to party finances. This approach, while administratively complex, would align funding with consent, addressing the core issue of taxpayer agency.

Ultimately, the taxpayer burden debate hinges on balancing democratic necessity with fiscal responsibility. While state funding can level the playing field for smaller parties, it must not come at the expense of taxpayer priorities. Policymakers should explore hybrid models, such as partial state funding combined with crowdfunding or membership fees, to reduce reliance on public money. Until then, taxpayers will continue to bear the weight of a system that, for many, feels like funding someone else’s political agenda with their hard-earned money.

When Does Political Violence Become a Necessary Evil?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

State funding for political parties can reduce their reliance on private donors, minimize corruption, and ensure a more level playing field for all parties, regardless of their ability to attract private funding.

While it uses taxpayer funds, state funding can be seen as an investment in democracy by promoting fair competition, transparency, and accountability in the political process.

Yes, state funding can reduce the disproportionate influence of wealthy individuals or corporations by providing parties with public resources, thereby decreasing their dependence on private contributions.

To prevent complacency, state funding is often tied to performance metrics, such as election results or membership numbers, ensuring parties remain accountable to voters.

State funding can be structured to support smaller parties, either through equal distribution or proportional allocation, helping them compete with larger, more established parties.