The question of whether white nationalism constitutes a political party is a complex and contentious issue. White nationalism, as an ideology, advocates for the belief that white people are a distinct racial group entitled to their own nation or state, often promoting policies of racial segregation and exclusion. While it is not a single, unified political party in the traditional sense, white nationalist movements and organizations have sought to influence politics through various means, including forming fringe political parties, infiltrating mainstream parties, or operating as loosely organized networks. In some countries, groups espousing white nationalist ideologies have attempted to gain political legitimacy by running candidates for office or advocating for policy changes that align with their racial agenda. However, due to the extreme and often violent nature of their beliefs, these groups are widely condemned by mainstream political parties and societies, leading to their marginalization and classification as hate groups rather than legitimate political entities.

Explore related products

$11.27 $19.99

$21 $14.95

What You'll Learn

Definition of White Nationalism

White nationalism is not a political party but an ideology rooted in the belief that white people constitute a distinct racial group entitled to their own nation or state. This ideology often advocates for policies that prioritize the interests of white individuals, frequently at the expense of other racial and ethnic groups. Unlike a political party, which operates within established democratic frameworks, white nationalism exists as a loosely organized movement with no centralized leadership or formal structure. Its adherents may align with various political parties or operate independently, but their core beliefs remain consistent: the preservation of white identity, culture, and dominance.

To understand white nationalism, it’s essential to distinguish it from related but distinct concepts like white supremacy. While white supremacy asserts the inherent superiority of white people over others, white nationalism focuses on the idea of racial separatism. White nationalists argue that different races should live apart to maintain their cultural and genetic purity. This distinction, however, is often blurred in practice, as both ideologies frequently overlap in their goals of maintaining white power and privilege. For instance, white nationalists may advocate for restrictive immigration policies or the creation of white-only communities, mirroring supremacist efforts to exclude non-white individuals from societal institutions.

The lack of a formal political party structure does not diminish the influence of white nationalism. Instead, it thrives through online networks, social media, and grassroots organizing, allowing it to adapt and spread rapidly. Platforms like forums, encrypted messaging apps, and alternative social media sites serve as breeding grounds for recruitment and radicalization. This decentralized nature makes it difficult to combat, as efforts to dismantle one group often lead to the emergence of others. For those seeking to counter white nationalism, understanding its organizational flexibility is crucial. Strategies must focus on disrupting online networks, promoting digital literacy, and fostering inclusive communities that challenge its divisive narratives.

A practical approach to addressing white nationalism involves education and awareness. Schools, workplaces, and community organizations can implement programs that teach the history of racism, the dangers of racial separatism, and the value of diversity. Parents and educators should monitor children’s online activities, particularly for exposure to extremist content, and engage in open conversations about race and identity. For policymakers, legislative measures such as banning hate groups, regulating online platforms, and funding anti-extremism initiatives are essential steps. However, these efforts must be balanced with protecting free speech and avoiding the alienation of marginalized communities.

Ultimately, the definition of white nationalism highlights its role as an ideology rather than a political party, but its impact on society is undeniable. By understanding its core tenets, organizational methods, and recruitment strategies, individuals and institutions can work together to counteract its influence. The fight against white nationalism requires vigilance, collaboration, and a commitment to fostering a society where equality and inclusion prevail. Without these efforts, the ideology will continue to exploit societal divisions, posing a persistent threat to democratic values and social cohesion.

Pink Floyd's Political Legacy: Revolution, Resistance, and Social Commentary

You may want to see also

Historical Origins and Growth

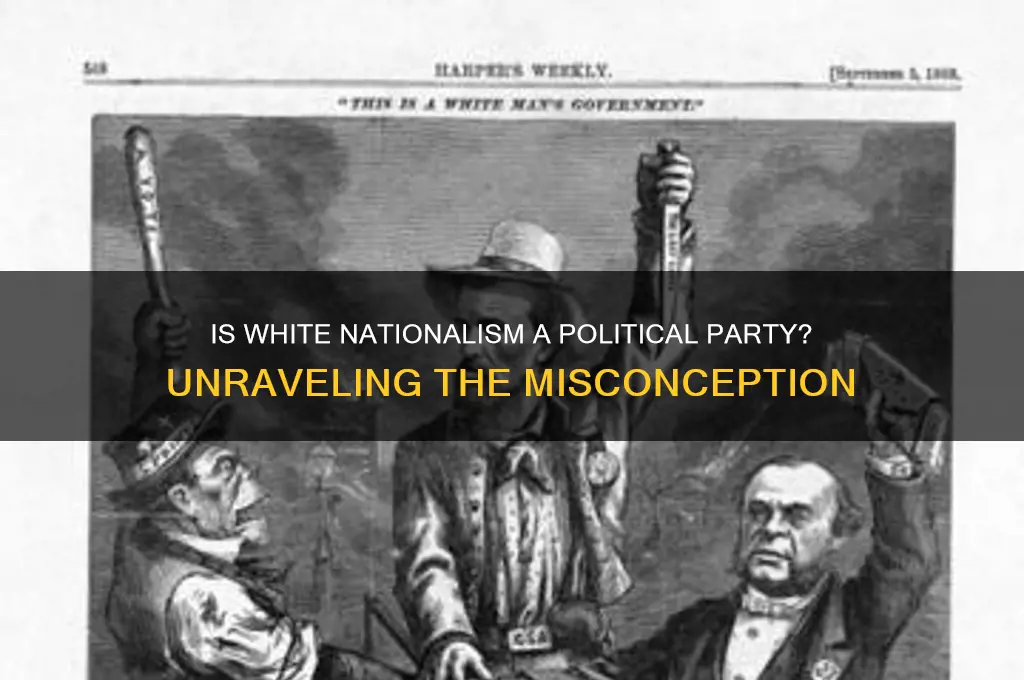

White nationalism, as a political ideology, did not emerge as a formal party but rather as a loosely organized movement with deep historical roots. Its origins can be traced back to the 19th century, when European colonialism and scientific racism provided intellectual scaffolding for the belief in white superiority. Thinkers like Arthur de Gobineau, whose 1853 essay *An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races* argued for the inherent dominance of the "Aryan race," laid the groundwork for later extremist ideologies. These ideas were not confined to academia; they permeated political discourse, influencing policies such as the Jim Crow laws in the United States and apartheid in South Africa.

The early 20th century saw the crystallization of white nationalist ideologies into more organized forms, often tied to fascist and Nazi movements. The rise of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party) in the 1930s exemplified how white nationalism could be weaponized into a state-sponsored ideology, with devastating global consequences. Post-World War II, white nationalist groups adapted to the new political landscape, operating as decentralized networks rather than formal parties. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan in the U.S. and the British National Front in the UK became focal points for these ideologies, though they lacked the centralized structure of traditional political parties.

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed the globalization of white nationalism, fueled by technological advancements and the rise of the internet. Online platforms enabled extremists to connect across borders, share propaganda, and recruit followers without the need for formal party structures. This period also saw the emergence of "suit-and-tie" white nationalists, who sought to rebrand extremism as a legitimate political stance. Figures like David Duke in the 1990s attempted to run for office, blurring the lines between movement and party politics. However, their efforts were largely unsuccessful in gaining mainstream acceptance, highlighting the ideological fringe nature of white nationalism.

In recent decades, white nationalism has experienced a resurgence, often cloaked in terms like "alt-right" or "identitarianism." Events such as the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, underscored its continued presence in contemporary politics. While some white nationalists have sought to form political parties—such as the American Freedom Party in the U.S.—these groups remain marginal, lacking the organizational cohesion and broad appeal of mainstream parties. Instead, white nationalism persists as a movement, drawing strength from its ability to adapt, evolve, and exploit societal divisions.

Understanding the historical origins and growth of white nationalism reveals its resilience as an ideology rather than a formal political party. Its decentralized nature allows it to thrive in the absence of centralized leadership, making it a persistent threat to democratic societies. Combating this ideology requires addressing its root causes—racism, inequality, and fear of demographic change—while remaining vigilant against its attempts to infiltrate political discourse. The lesson is clear: white nationalism may not be a party, but its impact on politics and society is undeniable.

How Political Parties Shaped Policies, Elections, and National Governance

You may want to see also

Key Beliefs and Goals

White nationalism is not a unified political party but a loosely organized ideology with adherents who may align with various extremist groups or operate independently. Despite this, its key beliefs and goals can be distilled into a coherent framework. Central to white nationalist ideology is the conviction that white people constitute a distinct racial group entitled to their own homogeneous nations or territories. This belief often manifests in the advocacy for ethnic homogenization, where non-white populations are seen as threats to cultural, genetic, or historical purity. Unlike traditional political parties with structured platforms, white nationalists rely on a mix of historical revisionism, pseudoscientific racial theories, and apocalyptic narratives to justify their goals. Their objectives typically include the establishment of white-only states, the deportation of non-whites, and the dismantling of multicultural societies, often framed as a survival imperative for the white race.

To understand their goals, consider the strategic use of fear and grievance. White nationalists exploit real or perceived threats—such as demographic shifts, immigration, or economic instability—to mobilize supporters. For instance, the "Great Replacement" theory, a cornerstone of their rhetoric, claims that white populations are being systematically replaced by non-white immigrants through deliberate policies. This narrative is not just a belief but a call to action, urging followers to resist what they perceive as a cultural and demographic genocide. Practical steps toward their goals often include infiltration of mainstream institutions, recruitment through online platforms, and the formation of paramilitary groups to enforce their vision of racial separation. These tactics underscore the movement’s adaptability and its ability to thrive in the absence of formal party structures.

A comparative analysis reveals that white nationalist goals diverge sharply from those of legitimate political parties. While traditional parties seek power through democratic processes and policy reforms, white nationalists reject pluralism and often advocate for violent revolution or secession. Their belief in racial hierarchy places them at odds with fundamental principles of equality and human rights. For example, their opposition to interracial marriage or multicultural education is not merely cultural conservatism but a deliberate attempt to enforce racial segregation. This distinction is critical: white nationalism is not a political ideology seeking compromise but a supremacist movement demanding dominance.

To counter their goals, it’s essential to dismantle the myths underpinning their beliefs. Education plays a pivotal role, particularly in exposing the pseudoscience behind racial superiority claims and the historical inaccuracies in their narratives. For instance, teaching the shared genetic heritage of humanity or the constructed nature of racial categories can undermine their core arguments. Additionally, addressing the socioeconomic grievances exploited by white nationalists—such as job insecurity or cultural displacement—requires inclusive policies that reduce alienation and foster solidarity across racial lines. Practical steps include supporting anti-racist legislation, monitoring extremist online activity, and promoting community-based initiatives that challenge hate with empathy and understanding.

Ultimately, the key beliefs and goals of white nationalism represent a dangerous rejection of diversity and equality. Their vision of a racially pure society is not only unattainable but inherently violent, requiring the suppression or expulsion of millions. By understanding their ideology as both irrational and strategically crafted, we can better combat its spread. This involves not just reactive measures but proactive efforts to build inclusive societies where the myths of white nationalism find no fertile ground. The absence of a formal party structure does not diminish their threat; it demands vigilance, education, and unity in opposition.

Why Politics Matters: Dooley's Perspective on Civic Engagement and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.49 $18.99

Legal Status and Recognition

White nationalism, as an ideology, does not inherently constitute a formal political party in most countries. However, groups advocating for white nationalist principles sometimes attempt to organize politically, seeking legal recognition to legitimize their agenda. The legal status and recognition of such entities vary widely depending on jurisdictional laws, societal norms, and the specific actions of these groups. In democracies with strong protections for freedom of association, white nationalist organizations may register as political parties if they meet procedural requirements, such as submitting a charter, disclosing funding sources, and gathering a minimum number of members. Yet, even in these cases, their recognition often triggers legal and societal scrutiny.

In countries like the United States, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech and assembly, allowing white nationalist groups to exist legally, though not necessarily as recognized political parties. For instance, the American Nazi Party operates as a political organization but lacks official party status due to its failure to meet state-specific registration criteria or its inability to garner sufficient electoral support. Conversely, in nations with stricter hate speech laws, such as Germany, white nationalist groups face outright bans. The German government prohibits organizations like the National Democratic Party (NPD) from formal recognition, citing their violation of constitutional principles, including human dignity and equality.

The process of gaining legal recognition as a political party is fraught with challenges for white nationalist groups. Many countries require parties to adhere to democratic values and reject discrimination, making it difficult for groups promoting racial superiority to qualify. For example, in Canada, the *Canada Elections Act* mandates that political parties respect the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, effectively barring white nationalist ideologies from formal recognition. Even when groups attempt to rebrand or moderate their language to meet legal standards, authorities often scrutinize their underlying objectives, leading to rejection or deregistration.

A critical takeaway is that legal recognition is not merely procedural but deeply tied to a society’s commitment to equality and human rights. While some argue that denying recognition stifles free expression, others contend that it prevents the normalization of harmful ideologies. Practical steps for policymakers include clarifying party registration criteria to explicitly exclude discriminatory platforms and strengthening enforcement mechanisms to monitor compliance. For activists and citizens, understanding these legal frameworks empowers them to challenge white nationalist groups’ attempts to legitimize their agenda through political systems. Ultimately, the legal status of white nationalist entities reflects a broader societal choice: whether to prioritize unfettered speech or protect vulnerable communities from hate-based mobilization.

Are Political Parties Exclusive? Analyzing Membership, Policies, and Representation

You may want to see also

Distinction from Political Parties

White nationalism, despite its attempts to infiltrate political discourse, fundamentally differs from a political party in structure, goals, and methods. Unlike parties that seek to win elections and govern through established institutions, white nationalist groups prioritize racial ideology over policy platforms. They lack the organizational hierarchy, membership criteria, and democratic processes typical of parties, instead operating as loosely connected networks or extremist movements. While some may attempt to disguise themselves as political entities, their focus remains on promoting racial superiority and segregation, not on achieving power through legitimate electoral means.

Consider the contrast in recruitment strategies. Political parties appeal to voters through policy proposals, candidate charisma, and grassroots organizing. White nationalist groups, however, often exploit social media, online forums, and fear-mongering narratives to radicalize individuals, particularly young men aged 18-35. Their "platform" consists of conspiracy theories, historical revisionism, and calls for racial purity, targeting those disillusioned with mainstream politics. This distinction highlights the insidious nature of white nationalism: it masquerades as a political alternative while functioning as a cult-like movement.

A critical distinction lies in the relationship to governance. Political parties, even those with extreme views, operate within the framework of democratic systems, aiming to influence or control state institutions. White nationalist groups, conversely, reject the legitimacy of existing governments and often advocate for the creation of racially homogeneous enclaves or the overthrow of multicultural societies. Their "political" actions—such as protests, propaganda dissemination, or even acts of violence—are not steps toward governance but tools to destabilize and intimidate. This rejection of democratic norms underscores their incompatibility with the concept of a political party.

Practically, distinguishing white nationalism from a political party is essential for countering its influence. Educators, policymakers, and community leaders should emphasize the movement’s lack of policy substance, its reliance on hate rather than governance, and its threat to democratic values. For instance, teaching media literacy to teenagers (ages 13-19) can help them identify white nationalist propaganda disguised as political discourse. Similarly, lawmakers must avoid legitimizing these groups by denying them access to political platforms or funding, while law enforcement should treat their violent actions as domestic terrorism, not political activism. By clarifying this distinction, society can better isolate and dismantle white nationalist ideologies.

Understanding Political Recall: Process, Power, and Public Accountability Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, white nationalism is not a recognized political party in the United States. It is an ideology, not a formal political organization.

While some extremist groups may align with white nationalist ideologies, there is no widely recognized or officially registered political party solely dedicated to white nationalism in most countries.

Mainstream political parties generally do not endorse white nationalist beliefs, as these views are widely considered extremist and discriminatory.

In countries with freedom of association, individuals can attempt to form political parties, but such parties would likely face legal and societal opposition if they promote hate or discrimination.

Yes, white nationalism is often described as a political movement or ideology rather than a formal political party, as it lacks centralized leadership and official party structures.