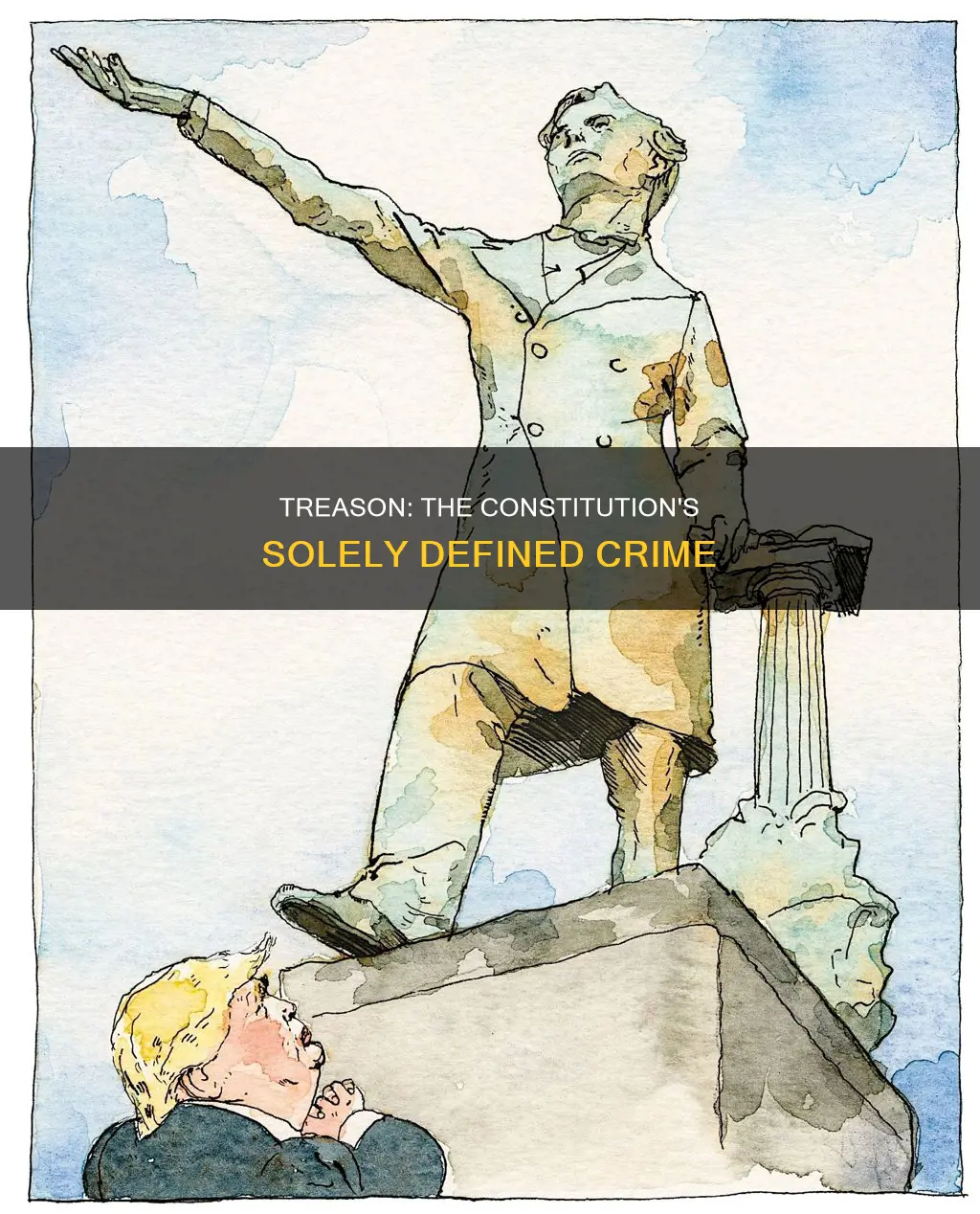

Treason is the only crime that is specifically defined in the US Constitution. Article III of the Constitution defines treason as levying war against the United States or adhering to [its] enemies, giving them aid and comfort. The Framers of the Constitution intended to create a restrictive definition of treason, limiting Congress's ability to punish the crime, and requiring a high standard of proof for conviction. This was in response to their experience with English law, where the crime of treason was often used to eliminate political dissidents. As such, treason is a significant crime in the United States, with a specific constitutional framework surrounding its prosecution and punishment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Treason defined in the Constitution | Yes |

| Treason the only crime defined in the Constitution | Yes |

| Requirements for treason conviction | Testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act or confession in open court |

| Protection against | Corrupt executive or Congress from expanding the definition of treason |

| Protection for | Free speech opposing a U.S. war effort |

Explore related products

$18.17 $59.99

What You'll Learn

The definition of treason

Treason is the only crime that is specifically defined in the US Constitution. According to Article III, a person is guilty of treason if they levy war against the United States or give "aid and comfort" to its enemies.

The Constitution uses the word "war" in only two places: in Article I, it allocates to Congress the power to "declare war"; and in Article III, it gives courts the power to hear cases requiring them to determine whether an individual is guilty of "levying war" against the United States. The Treason Clause is a powerful piece of textual evidence that courts are to play a role in evaluating individual threats to national security.

The Constitution specifically identifies what constitutes treason against the United States and limits the offence to two types of conduct: "levying war" against the United States, and "adhering to [its] enemies, giving them aid and comfort". The Framers of the Constitution intended to define treason narrowly, after their experiences with the English law of treason, which covered many actions against the Crown. They wanted to make it challenging to establish that someone had committed treason and to restrict Congress's power to change the definition of the crime and the proof needed to establish guilt.

The Supreme Court has further defined what each type of treason entails. The offence of "levying war" was interpreted narrowly in Ex parte Bollman & Swarthout (1807), a case stemming from a plot led by former Vice President Aaron Burr to overthrow the American government in New Orleans. The Supreme Court dismissed charges of treason against two of Burr's associates on the grounds that their conduct did not constitute levying war. Chief Justice Marshall was careful to state that this did not mean that a person could not be guilty of treason if they had not appeared in arms against the country. He emphasised that there must be an actual assembling of men for a treasonable purpose to constitute a levying of war.

Treason convictions must be based either on an admission of guilt in open court or on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act.

Citing Constitutional Amendments: APA Style Guide

You may want to see also

The history of the Treason Clause

The Treason Clause in the US Constitution defines treason as one of two acts: "levying war" against the United States or "adhering to [its] enemies, giving them aid and comfort". The Framers of the Constitution wanted to create a restrictive definition of treason, limiting the power of Congress to change the definition or the proof needed to establish the crime. This was due to their experiences with English law, where the ruling class used treason charges to eliminate political dissidents.

The Treason Clause also establishes that Congress has the power to set penalties for committing treason, but it cannot "work corruption of blood or forfeiture except during the life of the person" convicted. This means that family members of a convicted traitor cannot be prohibited from receiving or inheriting property from that person.

The Supreme Court has further defined what constitutes treason, particularly in the case of Ex parte Bollman & Swarthout (1807), which involved two associates of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was accused of plotting to overthrow the American government. The Court dismissed the treason charges against Bollman and Swarthout, interpreting "levying war" narrowly and stating that the crime of conspiracy to subvert the government "is not treason".

In Cramer v. United States (1945), the Supreme Court explored the history of the Treason Clause in depth. The Court held that the "two-witness principle" required the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act or a confession in open court to prove treason. This case also established that prosecutors could bring non-treason charges for conduct that could be considered treasonous, without providing the procedural safeguards of the Treason Clause.

The Treason Clause is designed to protect core individual rights, particularly freedoms of expression and dissent. It aims to prevent the government from using false or passion-driven accusations of treason to undermine political opponents. While treason prosecutions have mostly disappeared, they did attend nearly every armed conflict in American history up to and including World War II.

Who Were the Delegates at the Constitutional Convention?

You may want to see also

Treason prosecutions in American history

Treason is the only crime that is specifically defined in the US Constitution. It is defined as levying war against the United States or providing aid to its enemies. The Constitution also outlines the standard of proof for a treason conviction, requiring at least two witnesses to testify to the overt act in question.

Treason prosecutions have been rare in American history, with only one person indicted for treason since 1954. Here are some notable treason prosecutions and accusations in American history:

Ex parte Bollman & Swarthout (1807)

Former Vice President Aaron Burr was allegedly involved in a plot to overthrow the American government in New Orleans. Two of his associates, Bollman and Swarthout, were charged with treason but the Supreme Court dismissed the charges on the grounds that their conduct did not constitute levying war against the United States.

Jefferson Davis

The president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, was charged with treason after the Civil War. However, his prosecution was later abandoned as an effort at reconciliation.

Tokyo Rose (Iva Toguri D'Aquino)

During World War II, Iva Toguri D'Aquino, known as Tokyo Rose, made anti-American broadcasts and was convicted of "giving aid and comfort" to Japan. She served six years of a 10-year sentence before being pardoned by President Gerald Ford.

Adam Gadahn (Azzam the American)

Adam Gadahn, an American spokesman for al-Qaida, was indicted in 2006 for giving al-Qaida "aid and comfort ... with intent to betray the United States." However, he was killed by a US drone strike in Pakistan before he could be put on trial.

John Walker

During the Cold War, John Walker, a US Navy officer, sold secrets to the Soviet Union, compromising naval codes for nearly two decades.

Robert Hanssen

FBI agent Robert Hanssen passed secrets to the Soviet and Russian governments over 20 years, causing significant damage to American intelligence.

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold, a Revolutionary War hero, plotted to hand over a fort at West Point to the British, an act that was narrowly thwarted.

While these individuals faced treason accusations or prosecutions, the definition of treason in the US Constitution and the high standard of proof required have made convictions relatively rare.

Exploring the Preamble: Unveiling the Constitution's Iconic Quote

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Supreme Court's role in defining treason

Treason is the only crime that is defined in the US Constitution. It is defined as levying war against the United States or materially aiding its enemies. The Framers of the Constitution intended to define treason narrowly to prevent the political abuse of treason law, as they had experienced with the English law of treason. The Constitution also specifies the requirements for a treason conviction, including the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act or a confession in open court.

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in interpreting and applying the Treason Clause of the Constitution. In Ex parte Bollman & Swarthout (1807), the Court interpreted the offense of levying war narrowly, dismissing treason charges against two associates of former Vice President Aaron Burr. The Court held that there must be an actual assemblage of men for the purpose of executing a treasonable design to constitute levying war.

In Cramer v. United States (1945), the Supreme Court explored the history of the Treason Clause in depth and made treason more difficult to prove, although not impossible as conventional wisdom suggests. The Court's decision in Cramer established that prosecutors could bring non-treason charges without the procedural safeguards of the Treason Clause, even if the conduct could be considered treasonous.

In Haupt v. United States (1947), the Supreme Court upheld a treason conviction for the first time, finding that a father's acts of helping his son, a German spy, justified an inference of treasonous intent. The Court also clarified that treason has no geographical boundaries, holding that US citizens can be charged with treason for acts committed anywhere in the world.

The Supreme Court's interpretations of the Treason Clause have shaped the understanding of treason and influenced the prosecution of treasonous acts in American history.

Exploring the Dogmatic Constitution's Description of the Church

You may want to see also

The constitutional requirements for a treason conviction

Treason is the only crime that is specifically defined in the US Constitution. According to Article III, a person is guilty of treason if they levy war against the United States or provide aid to its enemies. The Constitution uses the word "war" in only two places: in Article I, it allocates Congress the power to "declare war"; and in Article III, it gives courts the power to determine whether an individual is guilty of "levying war" against the US.

The Framers of the Constitution intended to define treason narrowly, restricting Congress's power to change the definition of the crime and the proof needed to establish guilt. They wanted to make it challenging to establish that someone had committed treason, and to prevent the ruling class from using the crime of treason to eliminate political dissidents. The constitutional requirements for a treason conviction are as follows:

- A conviction of treason must be based either on an admission of guilt in open court or on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act.

- The witnesses must testify to the same overt act in question, and the defendant's intent.

- There must be an actual assembling of men for a treasonable purpose to constitute a levying of war.

- The defendant must be shown to have performed some part, however minute or remote from the scene of action, and to be actually leagued in the general conspiracy.

US Budget Breakdown: Where Does the Money Go?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, treason is the only crime specifically defined in the US Constitution.

The US Constitution defines treason as levying war against the United States or adhering to and providing aid or comfort to its enemies.

The Treason Clause is a part of the US Constitution that defines treason and establishes the requirements for a treason conviction. It also limits Congress's ability to punish the crime of treason.

![Alvin and the Chipmunks - Trick Or Treason [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61JHHG5KTDL._AC_UY218_.jpg)