The question of whether there is a correlation between education levels and political party affiliation has long been a subject of interest in political science and sociology. Research suggests that individuals with higher levels of education often lean towards more progressive or liberal political parties, while those with less formal education may gravitate towards conservative or populist movements. This trend is observed across various countries, though the strength and nature of the correlation can vary significantly based on cultural, economic, and historical contexts. Factors such as socioeconomic status, geographic location, and generational differences also play a role in shaping these political preferences. Understanding this relationship is crucial for policymakers, as it can inform strategies to bridge political divides and foster more inclusive democratic processes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Correlation in the U.S. | Studies show a consistent positive correlation between higher education levels and support for the Democratic Party. College-educated voters are more likely to lean Democratic, while those without a college degree tend to lean Republican. (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Global Trends | Similar patterns are observed in other democracies, where higher education often correlates with progressive or left-leaning political views. However, this varies by country and cultural context. (World Values Survey, 2022) |

| Urban vs. Rural Divide | College-educated individuals are more likely to live in urban areas, which tend to lean Democratic in the U.S., while rural areas with lower college attainment lean Republican. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023) |

| Issue Priorities | Highly educated voters prioritize issues like climate change, healthcare, and social justice, aligning with Democratic platforms, whereas less educated voters often focus on economic security and traditional values, aligning with Republican platforms. (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Generational Differences | Younger, more educated generations (e.g., Millennials and Gen Z) are more likely to support Democratic policies, while older, less educated generations may lean Republican. (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Income and Education | Higher education often leads to higher income, but the correlation with political party varies. Wealthy, highly educated individuals may still lean Republican due to fiscal conservatism. (Brookings Institution, 2023) |

| Gender and Education | Educated women are more likely to support Democratic candidates, while educated men show a weaker partisan divide. (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| Racial and Ethnic Factors | Among racial and ethnic groups, higher education levels generally correlate with Democratic support, but this varies (e.g., highly educated Asian Americans may lean Democratic, while highly educated White Americans show a stronger partisan split). (Pew Research Center, 2023) |

| International Education | In some countries, higher education correlates with support for centrist or conservative parties, depending on the political landscape (e.g., Germany, UK). (European Social Survey, 2022) |

| Causation vs. Correlation | While education correlates with party affiliation, causation is debated. Factors like socioeconomic status, geographic location, and cultural values also play significant roles. (American Political Science Review, 2023) |

Explore related products

$36.8 $52.99

$34.93 $71.99

What You'll Learn

Education level and voting behavior

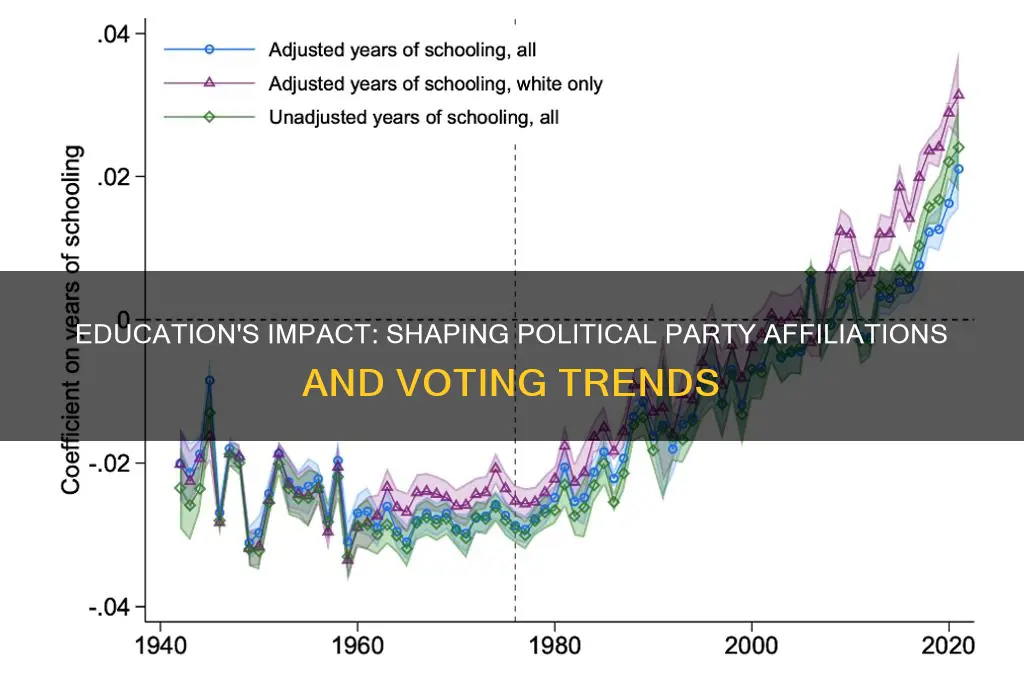

Education level significantly influences voting behavior, with higher educational attainment often correlating with specific political preferences. For instance, in the United States, college-educated voters have increasingly leaned toward the Democratic Party, while those without a college degree have shown stronger support for the Republican Party. This shift has been particularly notable since the 1990s, with the gap widening in recent elections. The Pew Research Center reports that in the 2020 presidential election, 58% of voters with a bachelor’s degree or higher supported the Democratic candidate, compared to 41% of those with a high school education or less. This trend suggests that education not only shapes individual policy preferences but also aligns voters with particular party platforms.

Analyzing this phenomenon reveals that education often fosters exposure to diverse ideas, critical thinking, and a broader understanding of complex issues, which can lead to different political priorities. For example, college-educated voters are more likely to prioritize issues like climate change, healthcare reform, and social justice, which are typically emphasized by Democratic candidates. Conversely, voters with lower educational attainment may focus on economic stability, traditional values, and local concerns, aligning more closely with Republican messaging. This divergence highlights how education acts as a lens through which individuals interpret political agendas and make voting decisions.

To understand this correlation better, consider the role of socioeconomic factors intertwined with education. Higher education often leads to higher income levels, urban residency, and exposure to multicultural environments, all of which can influence political leanings. For instance, urban areas with higher concentrations of college-educated residents tend to vote more progressively, while rural areas with lower educational attainment often lean conservative. However, it’s crucial to avoid oversimplification; education is not the sole determinant of voting behavior. Factors like age, race, gender, and regional culture also play significant roles, creating a complex interplay of influences.

Practical implications of this correlation are evident in campaign strategies. Political parties tailor their messaging to resonate with voters based on educational demographics. Democrats, for example, often emphasize investment in education, student loan forgiveness, and scientific research, appealing to college-educated voters. Republicans, on the other hand, may focus on job creation, tax cuts, and traditional values to connect with less-educated voters. Understanding these patterns can help voters critically evaluate campaign promises and ensure they align with their personal values and priorities.

In conclusion, the relationship between education level and voting behavior is a nuanced but powerful indicator of political alignment. While higher education tends to correlate with progressive voting patterns, lower educational attainment often aligns with conservative preferences. Recognizing this correlation can provide insights into broader societal trends and inform more effective political engagement. However, it’s essential to approach this relationship with an awareness of its limitations, acknowledging the multitude of factors that shape individual voting decisions.

Is the GOP Truly Liberal? Unraveling Political Ideologies and Labels

You may want to see also

Party affiliation by degree attainment

Educational attainment significantly influences political party affiliation, with higher degrees often correlating with specific partisan leanings. Data from the Pew Research Center and other studies consistently show that individuals with advanced degrees—such as master’s or doctoral degrees—are more likely to identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party. For example, in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, approximately 60% of voters with postgraduate degrees supported the Democratic candidate, compared to 37% who supported the Republican candidate. This trend reflects broader patterns where higher education is associated with progressive values, such as support for social justice, environmental policies, and government intervention in healthcare and education.

Conversely, those with lower levels of educational attainment, such as a high school diploma or less, are more likely to affiliate with the Republican Party. This group often prioritizes issues like economic nationalism, traditional values, and limited government, which align with Republican platforms. For instance, in the same 2020 election, 64% of voters without a college degree supported the Republican candidate, highlighting a stark divide based on educational background. This split is not merely about policy preferences but also reflects socioeconomic factors, as lower educational attainment often correlates with lower income and exposure to different political narratives.

The relationship between degree attainment and party affiliation is not static; it evolves with demographic and cultural shifts. Younger voters with college degrees, for example, are increasingly progressive, while older graduates may lean more moderately. Additionally, the type of degree matters—STEM graduates, for instance, may prioritize different issues than humanities graduates, leading to variations within the educated demographic. Understanding these nuances is crucial for political strategists and policymakers aiming to tailor messages to specific voter groups.

To leverage this correlation effectively, campaigns should segment their outreach based on educational demographics. For highly educated voters, emphasize policies addressing climate change, student debt, and healthcare reform. For those with less formal education, focus on economic stability, job creation, and local community issues. Practical tips include using data analytics to identify educational levels in target districts and crafting messages that resonate with each group’s priorities. For example, a campaign targeting college-educated suburban voters might highlight investment in renewable energy, while one targeting rural voters without college degrees might emphasize infrastructure improvements and trade policies.

In conclusion, party affiliation by degree attainment is a powerful lens for understanding political behavior. While higher education leans Democratic and lower education leans Republican, these trends are shaped by age, field of study, and socioeconomic factors. By recognizing these patterns and adapting strategies accordingly, political actors can more effectively engage diverse voter groups and address their unique concerns.

Unveiling SAM: Understanding the Political Party's Acronym and Core Principles

You may want to see also

Impact of schooling on policy preferences

Education level significantly influences policy preferences, shaping how individuals perceive and prioritize political issues. Studies consistently show that higher levels of education correlate with support for progressive policies such as healthcare reform, environmental protection, and social welfare programs. For instance, college-educated voters in the United States are more likely to favor government intervention in addressing climate change compared to those with a high school diploma or less. This trend is not unique to the U.S.; similar patterns emerge in countries like Germany and the UK, where educated voters tend to align with parties advocating for global cooperation and sustainable development.

The mechanism behind this correlation lies in the critical thinking and exposure to diverse perspectives that education fosters. Higher education often introduces students to complex societal issues, encouraging them to analyze problems from multiple angles. For example, a curriculum that includes courses on economics, sociology, or environmental science can equip students with the tools to evaluate policies like universal healthcare or carbon taxation. Conversely, limited access to such education may result in reliance on simpler, often emotionally charged narratives, which can align with more conservative or populist agendas.

However, the relationship between schooling and policy preferences is not linear. While education generally shifts preferences toward progressive policies, it can also polarize opinions. Highly educated individuals may develop stronger ideological convictions, leading to more extreme positions on issues like immigration or economic redistribution. For instance, a study in France found that while higher education correlated with support for the European Union, it also amplified divisions between pro-globalization and nationalist viewpoints. This suggests that education’s impact depends on the context in which it is received, including the political climate and the content of educational programs.

Practical steps can be taken to maximize the positive impact of education on policy preferences. Schools and universities should incorporate interdisciplinary courses that address real-world problems, encouraging students to engage with diverse viewpoints. For example, a course on public policy could include debates on healthcare systems, requiring students to research and defend different models. Additionally, educators should emphasize media literacy to help students critically evaluate political narratives. Parents and policymakers can also play a role by advocating for equitable access to quality education, ensuring that all students, regardless of socioeconomic background, have the opportunity to develop informed policy preferences.

In conclusion, schooling profoundly shapes policy preferences by fostering critical thinking and exposure to diverse ideas. While higher education generally aligns with progressive policies, its impact can vary based on context and content. By designing educational programs that encourage interdisciplinary thinking and critical engagement, society can harness the power of education to cultivate more informed and nuanced political viewpoints. This approach not only benefits individual voters but also contributes to a more robust democratic discourse.

Puerto Rico's Political Parties: Unraveling Their Colorful Identities and Meanings

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$24.57 $34.95

Higher education and political polarization

The relationship between higher education and political polarization is a complex interplay of exposure, identity, and institutional dynamics. College campuses, often portrayed as liberal bastions, do lean left on average, but this oversimplifies the reality. Research shows that higher education’s impact on political views is less about indoctrination and more about the diversification of perspectives students encounter. For instance, a 2019 study by the Pew Research Center found that while 59% of those with postgraduate degrees leaned Democratic, this shift was tied to increased exposure to diverse viewpoints and critical thinking skills, not ideological coercion.

Consider the mechanism: Higher education encourages engagement with conflicting ideas, which can either reinforce existing beliefs or prompt reevaluation. For example, a conservative student exposed to climate science courses might soften their stance on environmental regulation, not because of political bias, but due to evidence-based learning. Conversely, a liberal student in an economics class might question progressive tax policies after studying market dynamics. The key takeaway is that polarization isn’t inevitable; it’s often a byproduct of how individuals process this exposure.

To mitigate polarization, institutions can adopt practical strategies. First, foster interdisciplinary dialogue by requiring students to take courses outside their major or ideological comfort zone. For instance, pairing a political science class with a sociology course on community organizing can bridge theoretical and practical divides. Second, encourage faculty to model civil discourse by structuring debates that reward nuance over rhetoric. Third, create student groups focused on collaborative problem-solving, such as policy simulation exercises where participants must negotiate across party lines.

However, caution is warranted. While diversity of thought is beneficial, forcing ideological balance can backfire. For example, hiring conservative faculty solely for political representation risks tokenism if their expertise doesn’t align with academic standards. Similarly, free speech initiatives must balance openness with safeguards against harassment or misinformation. The goal isn’t to eliminate disagreement but to ensure it’s productive.

In conclusion, higher education’s role in polarization is neither monolithic nor deterministic. By structuring environments that encourage critical engagement without sacrificing intellectual rigor, colleges can cultivate informed citizens rather than entrenched partisans. The challenge lies in balancing exposure to diverse ideas with the development of skills to evaluate them—a delicate but achievable task.

Understanding Visibility Politics: Representation, Power, and Social Change Explained

You may want to see also

Educational disparities in party identification

Educational attainment significantly shapes political affiliations, with college-educated voters increasingly leaning Democratic in the U.S., while those without a college degree more often align with the Republican Party. This trend has intensified since the 1990s, creating a stark partisan divide along educational lines. For instance, in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, 65% of voters with a postgraduate degree supported the Democratic candidate, compared to 45% of those with a high school diploma or less. This disparity highlights how education acts as a proxy for broader socioeconomic and cultural factors influencing political identity.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the role of education in shaping worldview. Higher education often exposes individuals to diverse perspectives, fostering values like social liberalism and globalism, which align with Democratic platforms. Conversely, those with less formal education may prioritize local economic concerns or traditional values, resonating more with Republican messaging. For example, rural voters, who are less likely to hold college degrees, often support policies emphasizing job stability and cultural preservation, while urban, college-educated voters prioritize issues like climate change and healthcare reform.

However, this correlation isn’t universal. In Europe, the relationship between education and party identification varies by country. In Scandinavia, highly educated voters often support left-leaning parties, similar to the U.S. pattern. In contrast, in countries like Poland or Hungary, educated voters sometimes lean conservative, reflecting national contexts where higher education is tied to traditional or nationalist ideologies. This variability underscores the importance of cultural and historical factors in mediating the education-politics link.

Practical implications of this divide are significant. Policymakers must recognize that educational disparities in party identification can polarize political discourse, making bipartisan cooperation harder. For instance, debates over education funding or student loan forgiveness often become partisan battlegrounds, with college-educated Democrats advocating for reform and non-college Republicans expressing skepticism. Bridging this gap requires targeted messaging that acknowledges the distinct priorities of these groups, such as framing progressive policies in terms of economic opportunity for all education levels.

In conclusion, educational disparities in party identification are a critical lens for understanding modern political polarization. While higher education correlates with Democratic leanings in the U.S., this pattern varies globally, shaped by local contexts. Addressing this divide demands nuanced strategies that respect the diverse values and concerns of voters across educational backgrounds, fostering a more inclusive political dialogue.

Why Political Systems Often Feel Broken: Unraveling the Dysfunction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, research consistently shows a correlation between higher education levels and a greater likelihood of affiliating with the Democratic Party in the U.S., while lower education levels are often associated with Republican Party affiliation.

Yes, the correlation varies by country. In some nations, higher education may align with left-leaning parties, while in others, it could correlate with conservative or centrist parties, depending on cultural and historical contexts.

Education often exposes individuals to diverse perspectives, critical thinking, and progressive ideas, which can align with the values of certain political parties. Additionally, socioeconomic factors associated with education, such as income and occupation, play a role.

Yes, exceptions exist. Some highly educated individuals align with conservative parties, and some with lower education levels support progressive parties, often due to personal values, regional influences, or specific policy priorities.

The correlation can shape electoral outcomes, as parties may tailor their messaging to appeal to educated or less-educated voters. It also influences policy debates, as educated voters often prioritize issues like healthcare, climate change, and education reform.