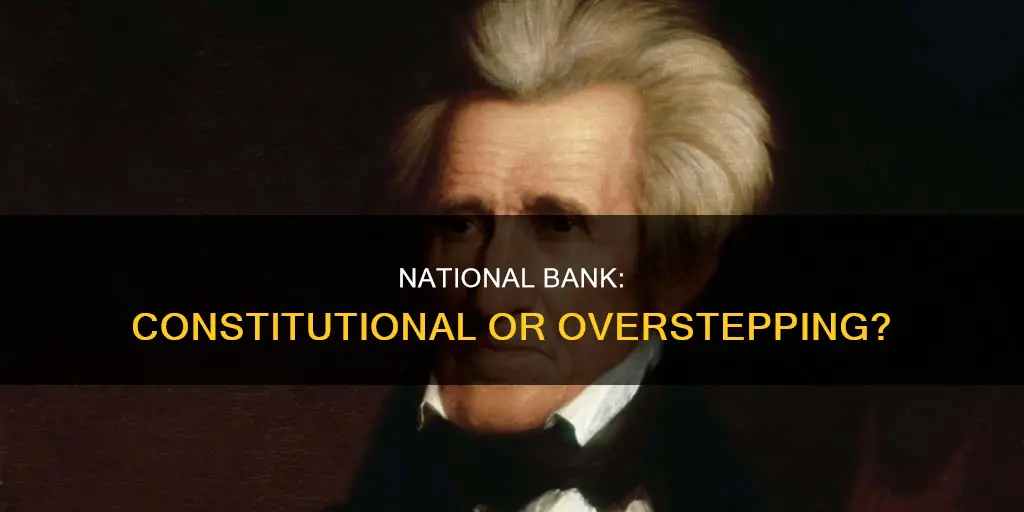

The establishment of a national bank in the United States has been a topic of debate since the late 18th century. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, proposed the creation of a national bank based on Great Britain's Bank of England. He envisioned government-developed bank branches in major cities, a uniform currency, and a central repository for federal funds. However, Thomas Jefferson, a prominent figure in the early days of the US, disagreed with Hamilton's plan, arguing that it was unconstitutional. Jefferson believed that a national bank would create a financial monopoly, favouring wealthy businessmen in urban areas over farmers and that the Constitution did not grant the government the authority to establish corporations. Despite the opposing views, Hamilton's proposal gained traction, and in 1791, President Washington signed it into law, establishing the First Bank of the United States.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Proponents of the establishment of a national bank | Alexander Hamilton, George Washington |

| Concerns about the establishment of a national bank | Thomas Jefferson, James Madison |

| Reasons for support | Funding for the government to purchase territory from foreign powers, based on the success of the British national bank |

| Reasons for opposition | Unconstitutional, undermines state banks, favours wealthy businessmen, violates civil liberties, creates a monopoly |

| Outcome | The Bank of the United States was established in 1791 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Thomas Jefferson believed a national bank was unconstitutional

Thomas Jefferson believed that a national bank was unconstitutional. In 1791, he opposed Alexander Hamilton's plan to create a national bank for the United States, modelled on the Bank of England. Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, wanted the government to establish bank branches in major cities, a uniform currency, and a place to deposit or borrow money.

Jefferson, however, argued that the Constitution did not grant the federal government the authority to establish corporations, including a national bank. He believed that the incorporation of a bank and the powers it assumed were not among the powers specifically enumerated in the Constitution. Jefferson also feared that a national bank would create a financial monopoly, undermining state banks and adopting policies that favoured urban financiers and merchants over rural farmers and plantation owners. He believed that states should charter their own banks.

Jefferson's opinion was that the existing banks would be willing to lend and compete for the government's business, and that being bound to a national bank would mean accepting their terms with no freedom to employ other banks. He also believed that the bill for establishing a national bank would enable it to receive grants of land, which would be against the laws of Mortmain.

The debate over the national bank was a significant moment in US history, marking the birth of the Republican Party and highlighting the differences in economic visions for the country. Jefferson saw the US as chiefly agrarian, while Hamilton's plan reflected a desire to develop banking, commerce, and industry. Despite Jefferson's opposition, a national bank was established when President Washington signed the bill into law in February 1791.

Roger Sherman's Influence on the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Jefferson's opinion on the bank undermining state banks

Thomas Jefferson believed that a national bank was unconstitutional. He feared that it would create a financial monopoly that might undermine state banks and adopt policies that favoured financiers and merchants, who tended to be creditors, over plantation owners and family farmers, who tended to be debtors. Jefferson's vision of the United States was that of an agrarian society, not one based on banking, commerce, and industry.

Jefferson also argued that the Constitution did not grant the government the authority to establish corporations, including a national bank. He believed that the creation of a national bank would violate the laws of Mortmain, Alienage, rules of descent, acts of distribution, laws of escheat and forfeiture, and the laws of monopoly. He thought that the Constitution only allowed the means that were "necessary" for effecting the enumerated powers, not those that were merely "convenient".

In contrast, Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, wanted to create a national bank based on Great Britain's national bank. He wanted the government to develop bank branches in major cities, have a uniform currency, and a place to deposit or borrow money when needed. Hamilton's plan was supported by President Washington, who signed the bill into law in February 1791.

Despite his opposition, Jefferson's views did not prevail, and a national bank was established. The Bank of the United States, commonly referred to as the First Bank of the United States, opened in Philadelphia on December 12, 1791, with a twenty-year charter.

Enlightenment Ideals: US Constitution's Core Principles

You may want to see also

Alexander Hamilton's proposal for a national bank

Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury, proposed the creation of a national bank in 1790. Hamilton's proposal was inspired by Great Britain's national bank, which was established in 1694 and played a critical role in the development of British imperial power in the 18th century. He argued that the "Bank of England unites public authority and faith with private credit, and hence we see what a vast fabric of paper credit is raised on a visionary basis."

Hamilton's proposal included the development of bank branches in major cities, a uniform currency, and a place for the federal government to deposit or borrow money when needed. He believed that a national bank would provide a source of funding for the US government to purchase large amounts of territory from foreign powers and help restore the value of the currency. The bank's branches in port cities would also make it easier for the federal government to collect tax revenues and finance international trade.

However, Hamilton's proposal faced opposition, particularly from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson argued that the Constitution did not grant the government the authority to establish corporations and that a national bank would create a financial monopoly that might undermine state banks and favour wealthy businessmen in urban areas over farmers. Madison, on the other hand, objected on the basis that Congress had no constitutional power to issue charters of incorporation.

Despite the opposition, Hamilton's proposal cleared both the House and the Senate after much debate. President Washington, who shared Hamilton's vision of vigorous national power, signed the bill into law in February 1791. The Bank of the United States, commonly referred to as the First Bank of the United States, opened in Philadelphia on December 12, 1791, with a twenty-year charter and $10 million in capitalization.

The Tax Court: Interpreting Constitution, Shaping Our Finances

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Hamilton's plan for the bank's branches and funding

Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury, proposed the creation of a national bank, the First Bank of the United States, in 1790. Hamilton's plan for the bank was inspired by the Bank of England and aimed to establish a strong and stable national currency, foster a powerful national economy, and address the country's economic woes, including widespread economic disruption, war debt, and inflation.

Hamilton envisioned the bank as a way to standardize American currency, consolidate states' war debts, and make the country financially competitive on a global scale. He proposed that the bank be funded through a combination of government investment and private capital. The federal government would own a portion of the bank, while the remaining capital would be held by private investors. This structure aimed to solidify the partnership between the government and the business classes.

Hamilton's plan for the bank's branches was to establish them in major port cities, including Boston, New York, Charleston, and Baltimore. This strategic placement facilitated the flow of money and credit around the country and made it easier for the federal government to collect tax revenues, as most taxes came from customs duties. The branches also played a crucial role in financing international trade and funding the country's westward expansion, particularly with the establishment of a branch in New Orleans.

The funding for the bank came from both government and private sources. The bank started with a capitalization of $10 million, with the U.S. government holding $2 million (20%) and private investors contributing the remaining $8 million (80%). This made the federal government a minority shareholder in the bank, while still benefiting from the financial stability and opportunities that the bank provided.

However, Hamilton's plan faced opposition, particularly from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson argued that the establishment of a national bank was unconstitutional and that it would create a financial monopoly that favoured wealthy urban businessmen over farmers. Madison, on the other hand, objected on the grounds that Congress lacked the constitutional power to issue charters of incorporation. Despite this opposition, Hamilton's plan ultimately prevailed, and the First Bank of the United States was established, opening for business in Philadelphia in 1791.

Founders' Slavery Treatment: A Constitutional Conundrum

You may want to see also

Congress' constitutional power to issue charters of incorporation

The question of whether the establishment of a national bank is constitutional has been a contentious issue in the history of the United States, with differing interpretations of the Constitution and the powers it grants to Congress.

The power of Congress to issue charters of incorporation and establish a national bank was a significant point of debate. The creation of a national bank required an act of incorporation from Congress, but critics argued that the Constitution did not explicitly grant Congress this power. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates the legislative powers of Congress, and the power to issue charters of incorporation is not explicitly mentioned. This absence was a central argument against the establishment of a national bank.

However, supporters of a national bank, including Alexander Hamilton, interpreted the "`necessary and proper` clause" of Article I, Section 8 broadly. They argued that it was "necessary and proper" for Congress to establish a national bank to carry out its explicitly stated powers, such as coining and regulating the value of money, borrowing money, and levying taxes. In his famous Report on a National Bank presented to the House of Representatives in 1790, Hamilton explained how his proposed system would operate, with Congress granting a twenty-year charter of incorporation to a Bank of the United States, funded by an initial deposit of $10 million.

The debate over the constitutionality of a national bank led to the landmark Supreme Court case McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819. The case addressed the issue of Federal power and commerce and the division of powers between the national government and the states. The Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that Congress had the implied power to incorporate a national bank under the "`elastic clause`" of the Constitution, which grants Congress the authority to "`make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution`" the powers of the Federal Government. This ruling set a precedent for the expansion of Federal power over states' rights.

In conclusion, while the establishment of a national bank and the issuance of charters of incorporation by Congress was a highly contested issue, the Supreme Court ultimately interpreted the "`necessary and proper` clause" broadly, granting Congress the constitutional power to establish a national bank and issue charters of incorporation as necessary means to execute its enumerated powers.

The Union's Perfect Harmony: Understanding Our Founding Ideals

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, wanted to create a national bank based on Great Britain's national bank. He believed that the government should develop bank branches in major cities, a uniform currency, and a place for the federal government to deposit or borrow money when needed.

Thomas Jefferson believed that the establishment of a national bank was unconstitutional. He argued that the Constitution did not grant the government the authority to establish corporations, including a national bank. He also believed that a national bank would create a financial monopoly that might undermine state banks and favour wealthy businessmen in urban areas over farmers in the country.

Despite the opposing voices, Hamilton's bill cleared both the House and the Senate after much debate. President Washington signed the bill into law in February 1791. The Bank of the United States, commonly referred to as the First Bank of the United States, opened for business in Philadelphia on December 12, 1791, with a twenty-year charter.

Yes, one major concern was the potential concentration of power in the Executive Branch and the Legislative Branch. James Madison, a critic of the proposal, argued that the creation of a national bank could lead to an overextension of congressional authority and a potential violation of individual civil liberties.

![TSPSC Group-II Paper-II Section-II Indian Constitution and politics Bit Bank 7500 Bits [ TELUGU MEDIUM ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91elCZwUZLL._AC_UY218_.jpg)