The question of whether a political party can be considered a demographic is a nuanced one, as it intersects the realms of political science and sociology. While demographics typically refer to statistical categories such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status, political parties are ideological and organizational entities that represent specific beliefs, values, and policy agendas. However, political parties often attract and mobilize distinct groups of people based on shared interests, cultural identities, or socioeconomic conditions, which can blur the lines between political affiliation and demographic characteristics. For instance, certain parties may disproportionately appeal to younger voters, rural populations, or specific ethnic groups, raising the question of whether party membership or alignment functions as a de facto demographic marker in shaping collective behavior and societal divisions. Thus, while not a traditional demographic, political parties can exhibit demographic-like qualities in their role as aggregators of diverse populations united by common political goals.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Party Membership Demographics: Analyzing age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status of political party members

- Voter Base Characteristics: Studying the demographic groups that consistently support specific political parties

- Geographic Distribution: Examining how party affiliation varies across urban, rural, and suburban areas

- Ideology and Demographics: Exploring how demographic factors influence political beliefs and party alignment

- Demographic Shifts Over Time: Tracking changes in party demographics due to generational or societal trends

Party Membership Demographics: Analyzing age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status of political party members

Political parties are not demographics in the traditional sense, but their membership often reflects distinct demographic patterns. Analyzing the age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status of party members reveals how these groups align with—or diverge from—broader societal trends. For instance, younger voters in many Western countries are more likely to affiliate with left-leaning parties, while older generations tend to lean conservative. This age-based divide is not universal, however; in some nations, economic policies or cultural values may override generational differences. Understanding these patterns is crucial for parties to tailor their messaging and policies effectively.

Consider gender dynamics: women are increasingly influential in progressive parties, often driven by issues like reproductive rights and gender equality. In contrast, conservative parties may attract more men, particularly those who prioritize traditional family structures or economic libertarianism. However, these trends are not absolute. For example, in Scandinavia, gender parity in party membership is more common across the political spectrum due to strong cultural norms around equality. Parties must recognize these nuances to avoid alienating potential supporters or reinforcing stereotypes.

Race and ethnicity play a pivotal role in shaping party demographics, particularly in diverse societies. In the United States, the Democratic Party has a strong base among African American and Hispanic voters, while the Republican Party traditionally draws more support from white voters. Yet, these patterns are shifting as minority groups grow in political influence and as parties adapt their outreach strategies. For instance, targeted campaigns addressing specific racial concerns—such as immigration reform or criminal justice—can reshape these dynamics. Parties that fail to engage diverse communities risk becoming increasingly homogeneous and out of touch.

Socioeconomic status is another critical factor. Working-class voters often align with parties promising economic security, whether through labor protections or welfare programs. Conversely, higher-income individuals may favor parties advocating for lower taxes or deregulation. However, this alignment is not always clear-cut. In some cases, cultural values—like attitudes toward globalization or climate change—can override economic self-interest. Parties must navigate this complexity by crafting policies that appeal to both the material and ideological priorities of their target demographics.

To effectively analyze party membership demographics, follow these steps: first, collect data through surveys, voter registration records, and exit polls. Second, segment the data by age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status to identify trends. Third, compare these findings with broader population data to highlight over- or under-representation. Finally, use this analysis to inform strategy—whether by adjusting policy platforms, reallocating resources, or launching targeted outreach campaigns. Caution: avoid reducing individuals to their demographic categories; intersectionality often reveals more nuanced motivations. By understanding these dynamics, parties can build coalitions that reflect the diversity of their electorates while advancing their political goals.

Political Philosophy's Impact: Shaping Governance, Society, and Individual Rights

You may want to see also

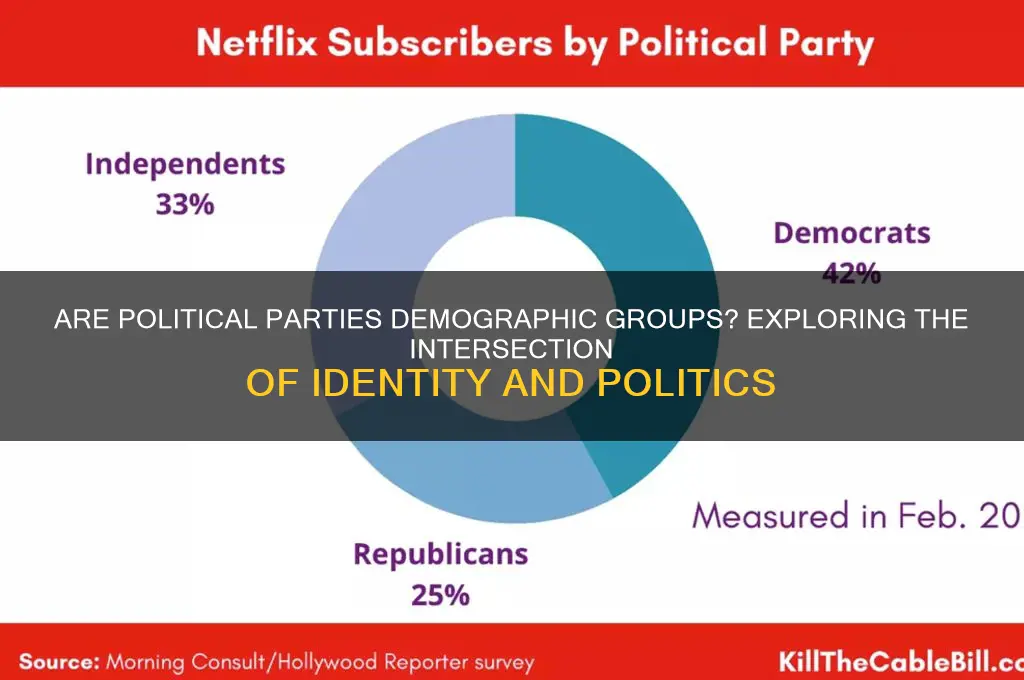

Voter Base Characteristics: Studying the demographic groups that consistently support specific political parties

Political parties often rely on core demographic groups for consistent support, creating a symbiotic relationship where policies and messaging are tailored to these voters’ needs. For instance, in the United States, the Democratic Party has historically garnered strong support from younger voters (ages 18–34), urban residents, and racial minorities, while the Republican Party tends to appeal to older voters (ages 55+), rural populations, and white, non-college-educated males. These patterns are not static; they evolve with societal changes, such as shifting immigration trends or economic disparities, but they provide a foundation for understanding voter behavior.

To study these voter base characteristics effectively, researchers employ quantitative methods like exit polls, census data, and surveys to identify correlations between demographic traits and party loyalty. For example, analyzing the 2020 U.S. presidential election reveals that 65% of Latino voters supported the Democratic candidate, while 58% of white voters without a college degree backed the Republican candidate. However, relying solely on broad categories can oversimplify complexities within groups. A more nuanced approach involves examining intersectionality—how factors like gender, income, and education overlap to shape political preferences. For instance, college-educated white women are more likely to vote Democratic than their non-college-educated counterparts, highlighting the need for granular analysis.

A practical tip for campaigns is to segment their outreach based on these demographic insights. For example, a party targeting younger voters might focus on social media platforms like TikTok or Instagram, emphasizing issues like climate change and student debt. Conversely, reaching older voters may require traditional methods like direct mail or local TV ads, with messaging centered on economic stability and healthcare. Caution must be exercised, however, to avoid stereotyping or alienating subgroups within broader demographics. Tailoring messages to specific concerns—such as addressing healthcare affordability for low-income families rather than assuming all minority voters prioritize the same issues—can enhance engagement.

Comparatively, international examples underscore the universality of demographic-party alignments. In India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) draws significant support from Hindu nationalists, particularly in rural areas, while the Indian National Congress appeals to secular, urban, and minority voters. Similarly, in the UK, the Labour Party traditionally relies on working-class voters and public sector employees, whereas the Conservative Party attracts older, wealthier, and rural constituents. These global patterns suggest that while cultural contexts differ, the principle of demographic targeting remains consistent across democracies.

In conclusion, studying voter base characteristics is essential for understanding the dynamics between political parties and their supporters. By combining data-driven analysis with a nuanced understanding of intersectionality, parties can craft strategies that resonate with specific demographics. However, this approach must be balanced with inclusivity to avoid marginalizing subgroups. As demographics shift and new issues emerge, ongoing research will remain critical to maintaining the relevance and effectiveness of political messaging.

Yesterday's Political Headlines: Key Events and Developments You Missed

You may want to see also

Geographic Distribution: Examining how party affiliation varies across urban, rural, and suburban areas

Political party affiliation often mirrors geographic divides, with urban, rural, and suburban areas exhibiting distinct partisan leanings. In the United States, for instance, urban centers like New York City and Los Angeles tend to favor Democratic candidates, while rural areas in the Midwest and South lean Republican. This pattern isn’t unique to the U.S.; in countries like the UK, urban areas often support Labour, while rural regions favor the Conservatives. Such trends suggest that population density, economic structures, and cultural values play a pivotal role in shaping political preferences. Understanding these geographic variations is essential for anyone analyzing electoral behavior or crafting targeted political strategies.

To examine these differences systematically, consider the following steps. First, analyze census data and election results to map party affiliation by zip code or county. Tools like GIS (Geographic Information Systems) can visualize these patterns, revealing clusters of support for specific parties. Second, correlate these maps with demographic data such as income levels, education rates, and industry dominance. For example, urban areas with high-tech industries and educated populations often lean left, while rural regions dependent on agriculture or manufacturing may lean right. Third, conduct surveys or focus groups in each area to uncover the underlying reasons for these preferences, such as attitudes toward government intervention or social issues.

Caution must be taken when interpreting these findings, as geographic distribution isn’t the sole determinant of party affiliation. Other factors, such as age, race, and gender, intersect with location to shape political identity. For instance, younger voters in rural areas may still lean progressive on issues like climate change, even if their region overwhelmingly supports conservative candidates. Additionally, suburban areas often serve as political battlegrounds, with shifting demographics and economic changes making their party leanings less predictable. Avoid oversimplifying these dynamics by treating geographic trends as absolute rather than probabilistic.

A practical takeaway for campaign strategists is to tailor messaging to the unique concerns of each geographic area. In urban settings, emphasize policies addressing housing affordability, public transportation, and social equity. In rural areas, focus on economic development, infrastructure, and local industries. Suburban voters, often prioritizing education and public safety, may respond to moderate, solutions-oriented platforms. By acknowledging the distinct needs and values of urban, rural, and suburban populations, political actors can build more inclusive and effective campaigns. This approach not only maximizes electoral success but also fosters a deeper understanding of the diverse constituencies that make up a democracy.

Banning Political Parties: Democracy's Future or Authoritarian Nightmare?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ideology and Demographics: Exploring how demographic factors influence political beliefs and party alignment

Demographic factors—age, race, gender, income, education, and geography—are not mere statistical categories but powerful predictors of political ideology and party alignment. For instance, younger voters in the United States (ages 18–29) are significantly more likely to lean Democratic, with 67% identifying with or leaning toward the party, compared to 53% of seniors (ages 65+), who are more evenly split. This generational divide underscores how life stage, cultural exposure, and economic concerns shape political preferences. Similarly, racial and ethnic groups exhibit distinct patterns: 92% of Black voters and 65% of Hispanic voters aligned with Democrats in the 2020 election, while 58% of white voters favored Republicans. These trends reveal how historical experiences, systemic inequalities, and policy priorities intersect with political identity.

To understand this dynamic, consider the role of education. College-educated voters are increasingly Democratic, with 57% supporting the party in recent elections, while non-college-educated whites tilt Republican (64%). This shift reflects the Democratic Party’s emphasis on issues like student debt relief and scientific expertise, which resonate with higher-educated voters. Conversely, Republicans’ focus on economic nationalism and traditional values appeals to working-class voters. Practical tip: Campaigns targeting specific demographics must tailor messages to align with these educational divides. For example, discussing job retraining programs might resonate with non-college-educated voters, while emphasizing research funding could appeal to college graduates.

Geography further complicates the relationship between demographics and ideology. Urban voters overwhelmingly lean Democratic, driven by diversity, progressive policies, and denser social networks. Rural voters, however, tend Republican, influenced by cultural conservatism and economic reliance on industries like agriculture and energy. This urban-rural split is not static; suburban areas, once reliably Republican, are now battlegrounds, with shifting demographics—such as an influx of younger, college-educated residents—tilting them Democratic. Caution: Overgeneralizing geographic trends can mislead. Even within rural areas, younger voters may hold more progressive views, signaling potential future shifts.

Income is another critical factor, though its influence is nuanced. While higher-income voters often lean Republican due to tax policies, this trend is offset by other demographics. For example, affluent minorities and women may prioritize social justice issues, aligning them with Democrats. Conversely, lower-income voters in rural areas may support Republicans due to cultural affinity, even if economic policies favor the wealthy. Comparative analysis shows that in Europe, social democratic parties often attract both working-class and educated voters, unlike the U.S., where these groups are more divided. This highlights how demographic factors interact with ideological frameworks across different political systems.

Finally, gender plays a subtle but significant role. Women are more likely to support Democratic candidates, with 57% identifying with the party, compared to 52% of men. This gap widens on issues like reproductive rights and healthcare, where Democratic policies align more closely with women’s priorities. However, this trend is not universal; white women without college degrees lean Republican, illustrating how gender intersects with other demographics. Takeaway: Political parties must navigate these intersections carefully. For instance, a campaign focusing on healthcare expansion should highlight how it benefits women, particularly in lower-income brackets, to maximize impact. Understanding these demographic influences is essential for crafting policies and messages that resonate with diverse voter groups.

Disney's Political Influence: Uncovering the Magic Kingdom's Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Demographic Shifts Over Time: Tracking changes in party demographics due to generational or societal trends

Political parties are not static entities; their demographics evolve in response to generational and societal shifts. For instance, the Democratic Party in the United States has seen a marked increase in racial and ethnic diversity over the past three decades, with non-white voters now comprising a majority of their base. Conversely, the Republican Party remains predominantly white, though efforts to appeal to younger, more diverse voters are evident in recent campaigns. These changes reflect broader societal trends, such as immigration patterns and shifting cultural norms, which reshape the electorate over time.

To track these shifts effectively, analysts must employ longitudinal studies that compare demographic data across decades. For example, the Pew Research Center’s surveys reveal that Millennials and Gen Z voters are significantly more likely to identify as independent or lean Democratic, driven by issues like climate change and social justice. In contrast, older generations, particularly the Silent Generation, remain more aligned with traditional Republican values. By examining these age-based trends, parties can tailor their messaging and policies to resonate with emerging voter blocs.

However, generational shifts are not the only drivers of demographic change. Societal trends, such as urbanization and educational attainment, also play a pivotal role. Urban areas, which tend to be more diverse and progressive, have increasingly become strongholds for Democratic voters. Meanwhile, rural regions, often characterized by homogeneity and conservatism, remain Republican bastions. Tracking these geographic and educational divides provides critical insights into how parties can adapt their strategies to appeal to specific demographics.

Practical tips for parties seeking to navigate these shifts include investing in data analytics to identify emerging trends and conducting focus groups with underrepresented groups. For instance, the Democratic Party’s outreach to Latino voters in the 2020 election involved targeted Spanish-language ads and community engagement initiatives. Similarly, the Republican Party’s efforts to attract younger voters have included emphasizing economic policies like tax cuts and entrepreneurship. By staying attuned to demographic changes, parties can ensure their relevance in an ever-evolving political landscape.

In conclusion, understanding demographic shifts is essential for political parties aiming to remain competitive. By analyzing generational and societal trends, employing data-driven strategies, and adapting to the needs of diverse voter groups, parties can effectively respond to the changing electorate. This proactive approach not only strengthens their appeal but also fosters a more inclusive and representative political system.

Understanding Machine Politics: Power, Patronage, and Urban Political Machines

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a political party is not a demographic. Demographics refer to statistical data about populations, such as age, gender, race, or income, while a political party is an organized group with shared political goals and ideologies.

Yes, political party affiliation can be included in demographic analysis as a variable, but it is not a demographic category itself. It is often used to understand voter behavior and preferences.

No, political parties are not classified as demographic groups. Demographic groups are defined by inherent characteristics like ethnicity or age, whereas political parties are voluntary associations based on ideology.

A political party is not considered a demographic because it is a choice-based affiliation, not an inherent trait. Demographics are based on fixed attributes, while party membership can change over time.

Political parties differ from demographic categories because they are formed around shared political beliefs and goals, whereas demographics are based on objective, measurable characteristics of a population.