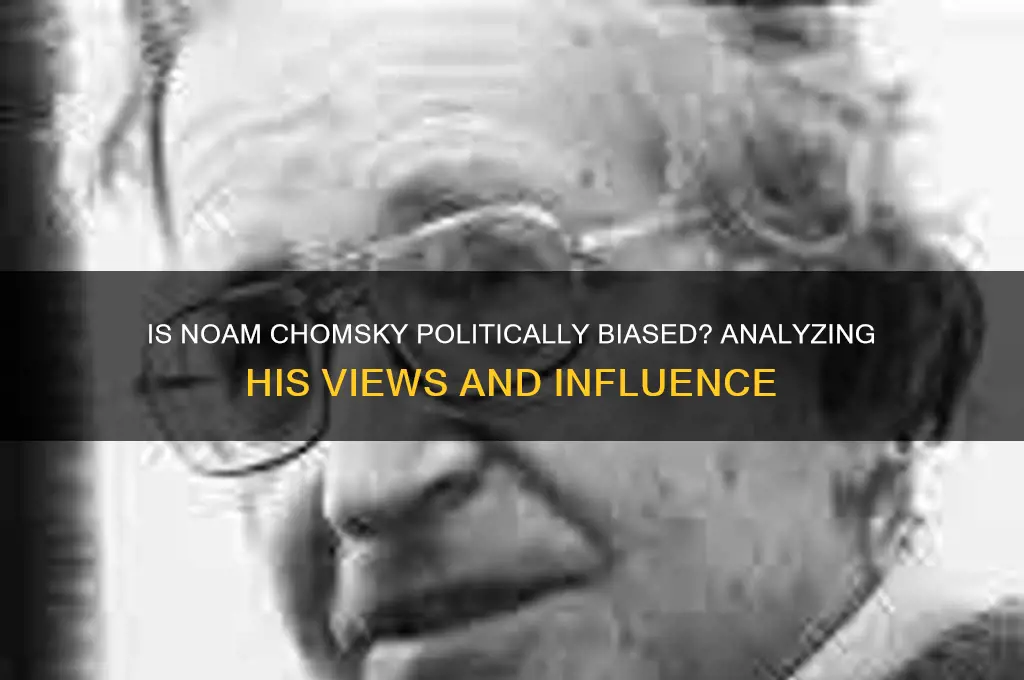

Noam Chomsky, a renowned linguist, philosopher, and political commentator, is often at the center of debates regarding political bias due to his outspoken critiques of U.S. foreign policy, capitalism, and mainstream media. While Chomsky identifies as an anarchist and libertarian socialist, his critics argue that his views consistently lean toward the left, portraying him as biased against conservative or neoliberal ideologies. Supporters, however, contend that his analyses are rooted in empirical evidence and a commitment to exposing systemic power structures, rather than partisan allegiance. The question of whether Chomsky is politically biased ultimately hinges on whether one views his critiques as ideologically driven or as a principled stance against injustice and inequality.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Chomsky's Political Views Overview

Noam Chomsky’s political views are often described as a blend of libertarian socialism, anarcho-syndicalism, and anti-imperialism, rooted in a critique of state power and corporate dominance. His intellectual framework emphasizes the importance of grassroots democracy, worker cooperatives, and the dismantling of hierarchical structures that perpetuate inequality. Chomsky’s analysis consistently targets what he sees as the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of elites, both domestically in the United States and globally through its foreign policy. This perspective has led him to critique both Republican and Democratic administrations, though his focus on U.S. imperialism and corporate influence often aligns him with the left.

To understand Chomsky’s alleged bias, consider his methodology: he relies heavily on historical documentation, declassified government records, and corporate archives to expose systemic injustices. For instance, his critique of U.S. interventions in Latin America, such as the 1954 CIA-backed coup in Guatemala, is grounded in extensive research rather than partisan rhetoric. This evidence-based approach distinguishes his work from ideological dogmatism, though critics argue his selection of topics—often focusing on Western wrongdoing—reflects a predisposition to highlight U.S. and capitalist failures.

Chomsky’s views on media further illustrate his political stance. He famously argues that corporate-owned media serves as a tool for manufacturing consent, shaping public opinion to align with elite interests. His book *Manufacturing Consent* (co-authored with Edward S. Herman) dissects this process, using case studies like the Vietnam War coverage to demonstrate media bias. While this critique is not inherently partisan, it resonates more strongly with those skeptical of establishment narratives, earning him both admiration and accusations of bias from detractors.

A practical takeaway from Chomsky’s perspective is his call for citizen engagement in counter-hegemonic movements. He advocates for supporting independent media, participating in labor unions, and challenging corporate and state power through nonviolent resistance. For example, he has praised the Zapatista movement in Mexico and the Rojava experiment in Syria as models of democratic self-organization. These endorsements reflect his consistent emphasis on bottom-up solutions over top-down governance, a theme that runs through his entire body of work.

Ultimately, Chomsky’s political views are not without controversy, but they are more accurately described as principled than biased. His critiques are rooted in a coherent ideological framework that prioritizes equality, democracy, and anti-imperialism. While his focus on U.S. and corporate malfeasance may appear one-sided, it stems from a belief that power must be held accountable, particularly when it harms the marginalized. Whether one agrees with him or not, Chomsky’s contributions force a reexamination of the structures that shape our world, making his perspective indispensable in debates about political bias.

Mastering Political English: Essential Tips for Effective Communication

You may want to see also

Criticism of U.S. Foreign Policy

Noam Chomsky's critique of U.S. foreign policy is a cornerstone of his intellectual legacy, often cited as evidence of his alleged political bias. At its core, Chomsky argues that U.S. foreign policy is driven by a consistent pursuit of economic and geopolitical dominance, frequently at the expense of human rights and democratic principles. This critique is not merely theoretical; Chomsky grounds it in historical examples, such as the U.S. support for authoritarian regimes in Latin America during the Cold War, the Vietnam War, and more recently, the "War on Terror." These cases, he contends, reveal a pattern of intervention that prioritizes strategic interests over moral imperatives.

To understand Chomsky's perspective, consider his analysis of the Vietnam War. He argues that the U.S. framed the conflict as a battle against communism to justify its actions, while the true motive was to suppress nationalist movements that threatened American economic and political influence in the region. This interpretation challenges the mainstream narrative, which often portrays U.S. interventions as benevolent efforts to spread democracy. Chomsky's method involves dissecting official rhetoric and comparing it with documented actions, a process he calls "manufacturing consent," where media and government collaborate to shape public opinion.

A practical takeaway from Chomsky's critique is the importance of critical media literacy. He urges individuals to question official narratives and seek diverse sources of information. For instance, during the Iraq War, Chomsky highlighted how the U.S. government and media amplified claims of weapons of mass destruction, which were later proven false. By examining the interests of those in power and cross-referencing multiple sources, one can better discern the motivations behind foreign policy decisions. This approach is not about rejecting all government statements but about fostering a healthier skepticism.

Comparatively, Chomsky's stance contrasts sharply with neoconservative or realist perspectives, which often defend U.S. foreign policy as necessary for global stability. While realists argue that states act rationally to secure their interests, Chomsky views this as a justification for exploitation. For example, he criticizes the U.S. role in the 1953 Iranian coup, where a democratically elected government was overthrown to protect oil interests, as a clear example of realpolitik gone wrong. This comparative analysis underscores Chomsky's belief that moral considerations should outweigh strategic ones in foreign policy.

Finally, Chomsky's critique is not without its detractors. Critics argue that his focus on U.S. misdeeds ignores the complexities of global politics and the actions of other nations. They claim that his analysis can oversimplify issues, such as the Cold War, where the U.S. and Soviet Union were locked in a struggle with no easy moral answers. However, Chomsky's defenders counter that his work is not about absolutes but about holding the powerful accountable. By consistently applying a critical lens to U.S. actions, he provides a counterbalance to dominant narratives, encouraging a more nuanced understanding of foreign policy. This ongoing debate highlights the value of Chomsky's contributions, even if one disagrees with his conclusions.

Art of Constructive Criticism: Mastering Polite Yet Effective Communication

You may want to see also

Support for Anarcho-Syndicalism

Noam Chomsky's support for anarcho-syndicalism is a cornerstone of his political philosophy, though it is often misunderstood or oversimplified. Anarcho-syndicalism, a branch of anarchism that emphasizes workers’ control of the means of production through labor unions, aligns with Chomsky’s critique of hierarchical structures and his advocacy for decentralized, democratic systems. This ideology is not merely theoretical for Chomsky; it is a practical framework for dismantling systemic inequalities and fostering genuine community empowerment. By advocating for workers’ self-management, Chomsky challenges the concentration of power in both state and corporate hands, arguing that true democracy must extend into the economic sphere.

To understand Chomsky’s stance, consider his frequent comparisons between capitalist and worker-controlled enterprises. He highlights historical examples, such as the Mondragon Corporation in Spain, where workers own and manage their cooperatives, demonstrating the viability of anarcho-syndicalist principles. Chomsky argues that such models reduce exploitation and foster solidarity, contrasting them with profit-driven systems that prioritize shareholder interests over human well-being. This comparative approach underscores his belief that anarcho-syndicalism is not utopian but a realistic alternative to existing economic structures.

Implementing anarcho-syndicalist ideas requires strategic steps. Chomsky suggests starting with grassroots organizing within existing labor unions, pushing for internal democratization and autonomy from political parties. He emphasizes the importance of education, encouraging workers to study cooperative management and collective decision-making. Practical tips include forming solidarity networks, engaging in strikes for self-management, and leveraging technology to coordinate decentralized efforts. However, Chomsky cautions against dogmatism, urging flexibility to adapt anarcho-syndicalist principles to local contexts and cultural norms.

Critics often label Chomsky’s views as idealistic or unfeasible, but his support for anarcho-syndicalism is rooted in a pragmatic critique of power dynamics. He acknowledges the challenges of transitioning from capitalist to worker-controlled systems but argues that incremental steps, such as supporting cooperatives and union-led initiatives, can build momentum. Chomsky’s takeaway is clear: anarcho-syndicalism is not a blueprint for revolution but a toolkit for incremental, meaningful change toward a more just society. His bias, if it can be called that, is toward empowering the working class and dismantling structures that perpetuate inequality—a stance that, while controversial, offers a coherent alternative to the status quo.

Is BLM Political? Exploring the Movement's Impact and Intentions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$58.49 $64.99

Media Analysis and Propaganda

Noam Chomsky’s critique of media bias and propaganda is rooted in his "Propaganda Model," outlined in *Manufacturing Consent*. This framework argues that media outlets, influenced by corporate ownership, advertising revenue, and government sources, systematically shape public opinion to align with elite interests. To analyze media through Chomsky’s lens, start by identifying the funding sources of a news organization. For instance, a network reliant on defense industry advertisements is likely to frame military interventions favorably. Next, examine the sourcing of stories. If a majority of quotes come from government officials rather than independent experts or affected communities, it suggests a bias toward establishment narratives. Finally, compare coverage of similar events in different geopolitical contexts. Chomsky highlights how Western media often portrays foreign leaders as dictators while downplaying authoritarianism in allied nations, revealing a double standard.

Consider the 2003 Iraq War as a case study. Chomsky argues that major U.S. media outlets amplified government claims about weapons of mass destruction without sufficient scrutiny, effectively acting as a mouthpiece for the Bush administration. This example illustrates how the Propaganda Model’s filters—ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak, and anti-communism (now expanded to anti-terrorism)—can distort public discourse. To apply this analysis, track how often a media outlet questions official narratives versus how often it repeats them. Tools like media bias charts or fact-checking websites can aid in this process, but Chomsky emphasizes the importance of critically examining the underlying structures, not just individual stories.

When dissecting propaganda, Chomsky urges readers to focus on *what is not said* as much as *what is said*. Omission is a powerful tool in shaping perception. For example, during the Cold War, Western media extensively covered human rights abuses in the Soviet Union while largely ignoring similar violations in U.S.-backed dictatorships. To counter this, diversify your news sources to include international and independent outlets. Al Jazeera, for instance, often provides perspectives absent in Western media. Additionally, engage with media literacy resources like the *Propaganda Model* itself or documentaries such as *The Corporation* to deepen your understanding of these mechanisms.

Chomsky’s critics argue that his analysis oversimplifies media dynamics and ignores the role of individual journalists’ integrity. While valid, this critique misses the point: the Propaganda Model is not about individual intent but systemic pressures. To test this, observe how media coverage shifts during election cycles or crises. Notice if outlets prioritize sensationalism over substance or if they frame issues in ways that benefit their advertisers. By doing so, you’ll develop a sharper eye for propaganda and a more informed perspective on media consumption.

Ultimately, Chomsky’s work challenges readers to become active, not passive, consumers of information. His analysis is not a call to cynicism but to vigilance. Start by asking: *Who benefits from this narrative?* Whether it’s a corporate merger framed as “economic growth” or a foreign policy decision labeled “humanitarian intervention,” this question can reveal hidden agendas. Pair this with a habit of cross-referencing stories across multiple sources, and you’ll begin to see media not as a neutral informer but as a contested terrain where power and truth collide. In an era of information overload, this critical approach is not just useful—it’s essential.

Princess Diana's Political Influence: Beyond Royalty, Shaping Global Change

You may want to see also

Stance on Israel-Palestine Conflict

Noam Chomsky's stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict is a critical lens through which to examine his alleged political bias. His views, often described as anti-imperialist and rooted in a critique of U.S. foreign policy, consistently challenge the narrative that Israel is a blameless victim in the conflict. Chomsky argues that Israel’s actions, particularly its occupation of Palestinian territories and expansion of settlements, violate international law and human rights. He frequently cites United Nations resolutions, such as UN Resolution 242, which calls for the withdrawal of Israeli forces from territories occupied in the 1967 war, to support his position. This analytical approach underscores his belief that Israel’s policies are not defensive but rather part of a systematic effort to maintain control over Palestinian land and resources.

To understand Chomsky’s perspective, consider his comparative analysis of global conflicts. He often contrasts the international response to Israel’s actions with reactions to similar situations elsewhere. For instance, he points out that while Russia’s annexation of Crimea faced widespread condemnation and sanctions, Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights has been met with relative impunity. This double standard, Chomsky argues, is a direct result of U.S. political and military support for Israel, which he views as enabling human rights abuses. His instructive tone here is clear: examine the inconsistencies in global justice to uncover underlying biases in foreign policy.

Chomsky’s persuasive arguments extend to the role of media in shaping public perception of the conflict. He critiques Western media outlets for framing Israel’s actions as necessary for self-defense while minimizing Palestinian suffering. For example, he highlights how Israeli airstrikes in Gaza, which often result in high civilian casualties, are portrayed as precise and justified, whereas Palestinian resistance is labeled as terrorism. This media bias, Chomsky contends, perpetuates a one-sided narrative that absolves Israel of accountability. To counter this, he encourages readers to seek alternative sources, such as independent journalists and human rights organizations, to gain a more balanced understanding of the conflict.

A descriptive examination of Chomsky’s work reveals his consistent advocacy for a two-state solution based on pre-1967 borders, with East Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine. He views this as a pragmatic step toward peace, though he remains critical of both Israeli and Palestinian leadership for failing to prioritize diplomacy. His cautionary note is that without external pressure, particularly from the U.S., Israel will continue to expand settlements, making a viable Palestinian state increasingly impossible. This takeaway is central to his argument: the conflict cannot be resolved without addressing the power imbalance and holding all parties accountable to international law.

In conclusion, Chomsky’s stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict is not merely a reflection of bias but a principled critique of power dynamics and moral consistency. His analytical, comparative, and persuasive approaches provide a framework for understanding the complexities of the conflict, while his descriptive and instructive insights offer practical steps for those seeking to engage with the issue critically. Whether one agrees with his views or not, Chomsky’s work challenges readers to question prevailing narratives and consider the human cost of political decisions.

Bridging Divides: Effective Strategies to Resolve Political Conflict Peacefully

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Noam Chomsky is openly politically biased. He identifies as an anarchist and libertarian socialist, and his views are consistently critical of capitalism, imperialism, and state power.

Yes, Chomsky’s political analysis is rooted in left-wing ideologies, particularly anarchism and socialism. He often critiques U.S. foreign policy and corporate influence from a progressive perspective.

Chomsky’s criticism of U.S. policies is not biased against the U.S. as a nation but against its government’s actions, particularly those he views as imperialistic or harmful to global populations.

While Chomsky’s academic work in linguistics is largely apolitical, his writings and speeches on politics, media, and society are explicitly informed by his left-wing political beliefs.

No, Chomsky’s views are not impartial or neutral. He openly advocates for specific political ideals and critiques systems he believes are unjust, making his perspective inherently biased toward his ideological stance.