The question Is my protest political? delves into the inherently intertwined nature of activism and politics, challenging individuals to examine the underlying motivations, goals, and societal implications of their actions. At its core, protest often seeks to challenge or reshape existing power structures, norms, or policies, which inherently places it within the political sphere, regardless of whether the intent is explicitly partisan or ideological. Even protests centered on seemingly apolitical issues, such as environmental conservation or social justice, inevitably engage with political systems and decision-making processes, as they demand accountability, change, or recognition from those in power. Thus, understanding the political dimensions of one’s protest is crucial for clarifying its impact, aligning it with broader movements, and navigating the complexities of advocacy in a politically charged world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Protests are inherently political if they aim to influence government policies, challenge power structures, or advocate for systemic change. |

| Target | If the protest targets political institutions, leaders, or decisions, it is considered political. |

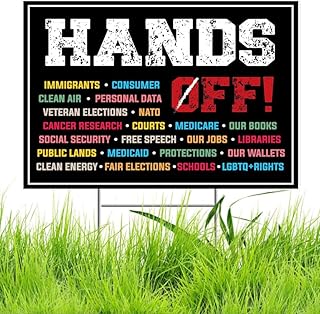

| Messaging | Political protests often involve slogans, signs, or speeches addressing social justice, equality, or governance issues. |

| Scale | Both small and large protests can be political, depending on their goals and impact. |

| Legality | Political protests may face legal challenges, especially if they disrupt public order or challenge authority. |

| Organizers | Protests organized by political groups, activists, or NGOs are more likely to be political. |

| Impact | Political protests aim to create societal or policy changes, not just raise awareness. |

| Historical Context | Protests rooted in historical political struggles (e.g., civil rights, labor rights) are inherently political. |

| Non-Political Exceptions | Protests focused solely on local, non-governmental issues (e.g., neighborhood noise) may not be political. |

| Global Relevance | Political protests often resonate with global movements or ideologies (e.g., climate justice, feminism). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Legal Boundaries of Protest: Understanding laws governing protests and potential legal consequences for participants

- Protest vs. Politics: Defining when activism crosses into political territory and its implications

- Motivations Behind Protests: Exploring personal, social, or ideological drivers of protest actions

- Impact on Political Systems: How protests influence policies, elections, and government decisions

- Non-Political Protest Forms: Identifying protests focused on social issues without direct political agendas

Legal Boundaries of Protest: Understanding laws governing protests and potential legal consequences for participants

Protests, by their very nature, challenge the status quo, but they exist within a legal framework that defines their boundaries. Understanding these boundaries is crucial for participants to ensure their actions remain protected and to anticipate potential legal consequences. Laws governing protests vary widely by jurisdiction, but common themes include restrictions on time, place, and manner. For instance, many regions require permits for large gatherings, prohibit obstruction of traffic or public spaces, and enforce noise ordinances. Ignoring these rules can lead to fines, arrests, or even criminal charges, depending on the severity of the violation.

Consider the case of a protest blocking a major highway. While the message may be powerful, such actions often violate laws against disrupting critical infrastructure. Courts have consistently upheld the right to protest but have also affirmed the state’s interest in maintaining public order. For example, in the U.S., the Supreme Court has ruled that protests cannot “unreasonably interfere” with the use of public spaces. Similarly, in the U.K., the Public Order Act 1986 grants police powers to impose conditions on protests to prevent “serious disruption to the life of the community.” Participants must weigh the impact of their actions against the legal risks involved.

To navigate these legal boundaries, protesters should take proactive steps. First, research local laws governing assemblies and demonstrations. Many cities have specific regulations, such as curfews or designated protest zones. Second, communicate with local authorities in advance. Obtaining a permit, when required, not only ensures compliance but also fosters cooperation with law enforcement. Third, document the protest. Video and witness accounts can be invaluable if legal disputes arise. Finally, understand the potential charges. Common offenses include trespassing, disorderly conduct, or failure to disperse. Knowing these can help participants make informed decisions during the event.

A comparative analysis reveals that legal consequences for protesters differ significantly across countries. In France, the *loi anti-casseurs* (anti-rioter law) allows authorities to ban individuals from protests if they pose a threat to public order, a measure criticized for its potential to suppress dissent. In contrast, Germany’s constitution explicitly protects the right to assemble without prior notification, though restrictions apply in certain areas like hospital zones. These variations underscore the importance of understanding local laws. For international activists, consulting legal experts or organizations like Amnesty International can provide tailored guidance.

Ultimately, the legal boundaries of protest are not designed to stifle dissent but to balance individual rights with societal needs. Participants must strike this balance by staying informed, planning carefully, and acting responsibly. While the law may limit certain actions, it also provides protections for legitimate expression. By understanding these boundaries, protesters can maximize their impact while minimizing legal risks, ensuring their voices are heard without unintended consequences.

Decoding US Politics: A Beginner's Guide to Understanding the System

You may want to see also

Protest vs. Politics: Defining when activism crosses into political territory and its implications

Protests inherently challenge the status quo, but the line between activism and politics blurs when demands shift from societal change to policy prescriptions. A protest advocating for "climate justice" remains broad and values-based, while one demanding "a 50% reduction in national carbon emissions by 2030" enters political territory by proposing a specific legislative target. This distinction matters because political protests invite scrutiny of feasibility, trade-offs, and implementation strategies, whereas broader calls for justice rely on moral persuasion.

Consider the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. While rooted in a moral demand for racial equality, specific chants like "Defund the Police" became political lightning rods. This slogan wasn’t merely symbolic; it proposed a concrete policy shift, sparking debates about budget reallocation, public safety, and alternative community support models. The shift from protest to politics forced activists to engage with the mechanics of governance, transforming their movement into a target for both legislative action and partisan backlash.

To navigate this terrain, activists must ask: *Does my protest demand a change in hearts and minds, or a change in laws and budgets?* A march against gender-based violence focuses on cultural attitudes, but a campaign for mandatory consent education in schools targets educational policy. The latter requires alliances with lawmakers, understanding of bureaucratic processes, and acceptance of compromise—hallmarks of political engagement. Practical tip: Frame demands in layers. Start with a universal value ("Equality for all") and pair it with a specific, achievable policy ask ("Pass the Equal Pay Act").

Crossing into political territory amplifies a protest’s impact but also exposes it to co-optation and division. Political protests become bargaining chips in partisan battles, as seen in the gun control movement post-Parkland, where student activists’ demands for assault weapon bans were weaponized in electoral campaigns. Caution: Maintain autonomy by diversifying tactics. Pair political lobbying with grassroots education campaigns to sustain momentum beyond legislative cycles.

Ultimately, the political nature of a protest isn’t a binary but a spectrum. Recognizing where your activism falls on this spectrum empowers strategic decision-making. For instance, a protest against corporate tax evasion can remain apolitical by focusing on ethical consumerism, or it can become political by advocating for a specific tax rate increase. The choice determines whether you’re rallying a movement or drafting a bill—both valid, but with distinct challenges and rewards.

Guatemala's Political Stability: Challenges, Progress, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Motivations Behind Protests: Exploring personal, social, or ideological drivers of protest actions

Protests are often perceived as overtly political acts, but their motivations can be deeply personal, rooted in individual experiences that spark a desire for change. Consider the case of a single mother protesting welfare cuts—her action is driven by the immediate threat to her family’s survival, not abstract political theory. Personal grievances, such as workplace discrimination or healthcare denial, frequently serve as catalysts for protest. These motivations are visceral, tied to one’s own suffering or the suffering of loved ones. For instance, a protester advocating for mental health resources might be motivated by a sibling’s struggle with untreated depression. Such actions, while political in outcome, begin with intimate, often private, pain. Recognizing this personal dimension humanizes protests, revealing them as extensions of individual resilience rather than mere ideological stances.

Social drivers of protest emerge from collective experiences that bind communities together, often in response to systemic injustices. Take the global Black Lives Matter movement—its momentum was fueled by shared outrage over racial violence and inequality, not isolated incidents. Social motivations thrive on solidarity, where individuals act not just for themselves but for the group’s well-being. For example, farmers protesting agricultural policies do so to protect their entire community’s livelihood. Social media amplifies these drivers, turning local issues into global causes. However, this collective nature can also dilute personal agency, as individuals may protest out of peer pressure or fear of ostracism. Balancing unity with individual conviction is key to sustaining socially driven protests.

Ideological motivations elevate protests from reactive to proactive, grounded in visions of a better society. Environmental protests, like those against fossil fuel expansion, are often driven by a commitment to sustainability, not immediate personal gain. Ideological protesters are typically well-versed in the theories they champion, whether it’s anarchism, feminism, or anti-capitalism. For instance, a protester advocating for universal basic income likely draws from economic theories and historical precedents. Yet, ideology can alienate those who prioritize tangible outcomes over abstract principles. Effective ideological protests bridge this gap by translating complex ideas into relatable narratives, such as framing climate action as a fight for future generations.

Understanding these motivations requires a nuanced approach, as protests rarely stem from a single driver. A worker striking for better wages might be motivated by personal financial strain (personal), union solidarity (social), and a belief in labor rights (ideological). Protest organizers should map these layers to craft inclusive messages. For instance, a campaign against police brutality could highlight individual stories, emphasize community safety, and invoke principles of justice. Conversely, critics of protests often oversimplify motivations, dismissing them as purely political or self-serving. By dissecting these drivers, we see protests not as monolithic acts but as multifaceted responses to complex realities. This perspective fosters empathy and strategic clarity, whether you’re a protester, organizer, or observer.

Is Fact-Checking Political? Uncovering Bias in Truth Verification

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99 $12.99

Impact on Political Systems: How protests influence policies, elections, and government decisions

Protests are not mere displays of dissent; they are catalysts for change within political systems. Historically, mass movements have reshaped policies, swayed elections, and forced governments to reconsider their decisions. For instance, the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong led to the withdrawal of the controversial extradition bill, demonstrating how sustained public pressure can compel legislative action. Similarly, the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 prompted cities across the U.S. to reallocate police budgets and enact police reform measures. These examples underscore the tangible impact protests can have on policy-making, proving that collective action often translates into concrete political outcomes.

To maximize the influence of a protest on political systems, organizers must strategically align their actions with specific policy goals. Start by identifying a clear, achievable demand—vague grievances rarely yield results. For example, instead of broadly opposing climate change, focus on demanding the closure of a specific coal plant or the implementation of a carbon tax. Next, leverage timing to your advantage. Protests held during election seasons or legislative sessions are more likely to capture policymakers’ attention. Finally, build coalitions with diverse groups to amplify your message and increase political pressure. A well-organized protest with a targeted agenda can force politicians to address issues they might otherwise ignore.

Critics often argue that protests are ineffective or counterproductive, but evidence suggests otherwise. Comparative analysis shows that nonviolent protests are twice as likely to succeed as violent ones, according to research by Erica Chenoweth. This is because nonviolent movements attract broader public support, maintain moral legitimacy, and are harder for governments to suppress. For instance, the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. achieved landmark legislation like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through nonviolent tactics. Conversely, violent protests often alienate potential allies and provide governments with justification for crackdowns. The takeaway? Nonviolence is not just a moral choice but a strategic one for influencing political systems.

Elections are another critical arena where protests exert influence. By mobilizing voters and shaping public discourse, protests can alter electoral outcomes. The 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, for example, brought income inequality to the forefront of political debates, influencing the platforms of candidates in subsequent elections. Similarly, protests against healthcare policy changes in the U.S. have historically swayed public opinion and pressured lawmakers to reconsider their stances. To harness this power, protesters should focus on educating the public about the political implications of their cause and encouraging voter turnout. When protests become part of the electoral narrative, they can shift the balance of power in favor of their demands.

Finally, protests serve as a check on government overreach and a mechanism for holding leaders accountable. In authoritarian regimes, where traditional avenues for dissent are limited, protests often become the primary means of challenging state power. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011, though not uniformly successful, demonstrated the potential for mass movements to topple long-standing dictatorships. Even in democratic systems, protests act as a reminder to elected officials that their decisions are subject to public scrutiny. By consistently applying pressure, protesters can ensure that governments remain responsive to the needs and demands of their citizens. In this way, protests are not just political acts—they are essential tools for maintaining a healthy, accountable political system.

Your Political Compass: How Ideology Shapes Your Final Moments

You may want to see also

Non-Political Protest Forms: Identifying protests focused on social issues without direct political agendas

Protests often blur the lines between social and political spheres, but not all demonstrations are inherently political. Consider the March for Our Lives, a movement sparked by students advocating for gun control after the Parkland shooting. While gun legislation is a political issue, the core of their protest was a social plea for safety in schools—a demand rooted in community well-being rather than partisan agendas. This distinction highlights how protests can address systemic problems without aligning with political ideologies.

To identify non-political protest forms, focus on intent and scope. For instance, a community rally demanding cleaner water in a polluted neighborhood targets a social issue directly affecting residents’ health. While environmental regulations are political, the protest itself may bypass partisan debates, emphasizing immediate local needs. Similarly, a strike by factory workers for fair wages addresses a social injustice without necessarily endorsing a political party or policy. The key is to examine whether the protest’s primary goal is to rectify a societal harm rather than to influence political power structures.

Practical steps can help organizers ensure their protest remains non-political. First, frame demands in universally relatable terms—focus on human rights, dignity, or community survival rather than legislative specifics. For example, instead of advocating for a particular bill, emphasize the right to safe living conditions. Second, avoid partisan symbols or slogans that could alienate participants with differing political views. Third, collaborate with diverse groups to amplify the social issue’s universality. A protest against domestic violence, for instance, can unite people across political divides by centering on shared values of safety and justice.

However, challenges arise when external actors politicize non-political protests. Media narratives, counter-protests, or opportunistic politicians can reframe social issues as partisan battles. To mitigate this, organizers should consistently communicate the protest’s non-political nature through clear messaging and actions. For example, a protest against racial profiling by police can explicitly state it seeks accountability and reform, not the defunding or abolition of law enforcement—a politically charged demand. By maintaining focus on the social issue, the protest retains its non-political character.

In conclusion, non-political protests are powerful tools for addressing social issues without engaging in partisan agendas. By centering on shared human experiences and avoiding political jargon, these movements can foster unity and drive meaningful change. Whether advocating for safer schools, cleaner water, or fair wages, the essence lies in the collective demand for a better society—not in the political mechanisms to achieve it. This approach not only broadens participation but also ensures the protest’s impact resonates beyond ideological divides.

Mastering Polite Texting: How to Communicate Respectfully with Your Teacher

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, protests addressing social issues are inherently political because they challenge or advocate for changes in policies, systems, or government actions.

While local issues may seem less partisan, they often involve government decisions or policies, making them political in nature.

Yes, protests advocating for personal freedoms are political because they engage with laws, regulations, or government authority.

No, a protest is political if it addresses any issue related to governance, policies, or societal structures, regardless of whether it targets a specific party or leader.