The question of whether Islam is simply a religion or also functions as a political party is a complex and multifaceted issue that has sparked considerable debate among scholars, policymakers, and the general public. While Islam is fundamentally a faith system with spiritual, moral, and ethical teachings rooted in the Quran and the life of Prophet Muhammad, its historical and contemporary role in shaping governance, law, and societal structures cannot be overlooked. In many Muslim-majority countries, Islamic principles have been integrated into political systems, influencing legislation, judicial practices, and even the formation of political parties that advocate for Sharia law. This intersection of religion and politics has led some to argue that Islam inherently carries political dimensions, while others maintain that its political manifestations are interpretations rather than core tenets. Understanding this duality requires examining the diverse ways in which Islam is practiced and interpreted across cultures, as well as the historical contexts that have shaped its relationship with power and authority.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Islam is primarily a religion based on the teachings of the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad, focusing on spiritual beliefs, worship, and moral conduct. |

| Political Involvement | Historically, Islam has influenced political systems, particularly in Islamic states where Sharia law is implemented. However, not all Muslims advocate for political Islam. |

| Diversity of Views | Muslims hold diverse political beliefs, ranging from secularism to Islamism, reflecting individual interpretations and cultural contexts. |

| Separation of Religion and State | Many Muslim-majority countries have secular governments, while others integrate religious principles into governance. |

| Global Presence | Islam is a global religion with over 1.9 billion followers, not confined to any single political ideology or party. |

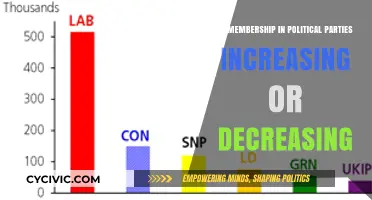

| Political Parties | Some political parties in Muslim-majority countries are explicitly Islamic, but many Muslims participate in non-religious political movements. |

| Individual vs. Collective Identity | For some, Islam shapes political views; for others, it is purely a personal faith with no political implications. |

| Historical Context | Islam has historically served as both a religious and political framework, but modern interpretations vary widely. |

| Criticism and Debate | Debates exist on whether Islam inherently blends religion and politics or if this is a misinterpretation by certain groups. |

| Conclusion | Islam is fundamentally a religion, but its intersection with politics varies based on individual, cultural, and historical factors. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Role of Islam in Governance: Examines Islam's influence on political systems throughout history

- Sharia Law and Modern Politics: Explores Sharia's role in contemporary political frameworks and debates

- Muslim Political Movements: Analyzes organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood and their political agendas

- Secularism vs. Islamic States: Compares secular governance with states claiming Islamic political authority

- Religion vs. Political Identity: Investigates when Muslim identity shifts from religious to political affiliation

Historical Role of Islam in Governance: Examines Islam's influence on political systems throughout history

Islam's historical role in governance is not merely a footnote in the annals of political history but a central narrative that has shaped civilizations. From the Rashidun Caliphate to the Ottoman Empire, Islamic principles have been the bedrock of political systems, blending religious doctrine with administrative pragmatism. The Quran and Hadith provided a moral and legal framework, while institutions like the Sharia courts ensured justice and order. This fusion of faith and governance created a unique model where the ruler was both a spiritual leader and a temporal authority, a concept that challenged the secular-religious divide prevalent in other societies.

Consider the Abbasid Caliphate, a golden age of Islamic governance spanning from 750 to 1258 CE. This era exemplifies how Islam influenced political systems by fostering intellectual and cultural advancements. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad became a hub for translating and preserving knowledge from Greek, Persian, and Indian civilizations, all under the patronage of caliphs who saw governance as a divine responsibility to uplift society. Here, Islam was not just a religion but a guiding philosophy that integrated faith, science, and administration, proving that its role extended far beyond spiritual matters.

However, the historical role of Islam in governance is not without its complexities. The Mamluk Sultanate, for instance, demonstrated how Islamic principles could be both unifying and divisive. While the Mamluks upheld Sharia law and protected Islamic territories, their political structure was often marked by power struggles and military dominance. This duality highlights a critical takeaway: Islam’s influence on governance has been as diverse as the societies that adopted it, shaped by local contexts, leadership styles, and historical circumstances.

To understand Islam’s role in governance today, one must study its historical adaptations. For example, the concept of *ijtihad* (independent reasoning) allowed scholars to interpret Islamic law in ways that addressed contemporary challenges. This flexibility enabled Islamic governance to evolve, from the decentralized tribal systems of early Arabia to the centralized bureaucracies of later empires. Practical tip: When analyzing modern Islamic political movements, trace their roots to these historical precedents to grasp their motivations and methodologies.

In conclusion, Islam’s historical role in governance is neither monolithic nor peripheral. It has been a dynamic force, shaping political systems through its moral, legal, and intellectual contributions. By examining its past, we gain insights into how religion and politics can intertwine constructively, offering lessons for both Islamic and non-Islamic societies navigating the complexities of faith and governance in the modern world.

Understanding Political Party Platforms: Core Components and Key Issues Explained

You may want to see also

Sharia Law and Modern Politics: Explores Sharia's role in contemporary political frameworks and debates

Sharia law, derived from the Quran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, serves as a moral and legal framework for Muslims. In contemporary political discourse, its role is often debated, with some viewing it as a religious code and others as a political ideology. This duality raises questions about whether Islam functions solely as a religion or if it inherently carries political dimensions. To understand Sharia’s place in modern politics, one must examine its implementation, interpretation, and the contexts in which it intersects with governance.

Consider the example of countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, where Sharia is enshrined in the constitution and shapes legal systems, education, and social norms. In these nations, religious authority and political power are intertwined, blurring the line between faith and state. Conversely, in secular Muslim-majority countries such as Turkey or Indonesia, Sharia plays a more limited role, often confined to family law or personal status matters. These contrasting models highlight how Sharia’s political influence depends on its integration into a nation’s legal and political framework.

The debate over Sharia in politics is further complicated by its interpretation. Traditionalists argue for a strict, literal application, while reformists advocate for contextual adaptation to modern values. This divide often manifests in political movements, with groups like the Muslim Brotherhood or Pakistan’s Tehreek-e-Insaf leveraging Sharia as a rallying point for political agendas. Critics, however, warn that politicizing Sharia can lead to authoritarianism or the marginalization of minority rights, as seen in instances where rigid interpretations have been enforced.

For policymakers and citizens navigating this terrain, a nuanced approach is essential. Sharia can coexist with democratic principles if interpreted flexibly and applied selectively, focusing on areas like ethics and personal conduct rather than criminal or constitutional law. Practical steps include fostering interfaith dialogue, promoting legal pluralism, and ensuring that any implementation of Sharia aligns with international human rights standards. This balanced approach allows Sharia to retain its religious significance without becoming a tool for political domination.

Ultimately, the role of Sharia in modern politics reflects broader tensions between religion and governance. Whether viewed as a religious guide or a political manifesto, its influence hinges on interpretation and context. By understanding these dynamics, societies can navigate the complexities of Sharia’s role, ensuring it serves as a unifying force rather than a divisive one.

Who Oversees Political Donations: Understanding Campaign Finance Regulations

You may want to see also

Muslim Political Movements: Analyzes organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood and their political agendas

The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna, exemplifies how Islamic principles can be translated into a political agenda. Emerging in Egypt as a response to colonialism and secularization, the organization advocates for the establishment of an Islamic state governed by Sharia law. Its motto, "Islam is the solution," encapsulates its belief that societal and political problems can be resolved through a return to Islamic values. This fusion of religion and politics challenges the notion that Islam is solely a spiritual practice, positioning it as a comprehensive ideology with governance implications.

Analyzing the Muslim Brotherhood’s structure reveals a hierarchical organization with local, national, and international branches. It operates through grassroots initiatives, providing social services like education, healthcare, and charity, which bolster its popularity among marginalized communities. These activities serve a dual purpose: addressing societal needs while embedding Islamic principles into public life. However, this approach has sparked debates about whether such organizations exploit religion for political gain or genuinely seek to integrate faith into governance.

A comparative examination of the Muslim Brotherhood’s political agenda highlights its adaptability across contexts. In Egypt, it has oscillated between political participation and suppression, culminating in its designation as a terrorist organization in 2013. In contrast, its affiliates in countries like Tunisia (Ennahda) and Morocco (Justice and Development Party) have adopted more pragmatic approaches, engaging in democratic processes and moderating their stances on Sharia implementation. These variations underscore the complexity of labeling such movements as purely religious or political.

Critics argue that the Muslim Brotherhood’s ultimate goal is to establish a global caliphate, a claim the organization denies. This accusation reflects broader anxieties about Islamism and its potential to undermine secular governance. Proponents, however, view the Brotherhood as a legitimate political actor striving for justice and self-determination within an Islamic framework. This dichotomy highlights the challenge of categorizing Muslim political movements: are they religious entities with political aspirations, or political parties cloaked in religious rhetoric?

To navigate this question, one must consider the practical implications of such movements. For instance, their emphasis on Sharia law raises concerns about human rights, particularly regarding gender equality and religious minorities. Yet, their ability to mobilize masses and address governance failures cannot be ignored. Policymakers and analysts must approach these organizations with nuance, recognizing their multifaceted nature and the diverse contexts in which they operate. Understanding the Muslim Brotherhood and similar movements requires moving beyond binary classifications, acknowledging that religion and politics are often intertwined in ways that defy simple categorization.

Why Midterm Elections Shape Our Future: The Politics That Matter

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Secularism vs. Islamic States: Compares secular governance with states claiming Islamic political authority

The distinction between secular governance and Islamic states hinges on the role of religion in political authority. Secular states, by definition, separate religion from state affairs, ensuring that laws and policies are derived from civic consensus rather than religious doctrine. In contrast, Islamic states claim to derive their political legitimacy and legal frameworks from Sharia, or Islamic law, as interpreted from the Quran and Hadith. This fundamental difference shapes governance, legal systems, and societal norms in profound ways.

Consider the legal systems of secular and Islamic states. In secular nations like France or India, laws are enacted through legislative processes, often reflecting pluralistic values and international human rights standards. For instance, France’s *laïcité* enforces strict separation of church and state, prohibiting religious symbols in public institutions. Conversely, in Islamic states like Saudi Arabia or Iran, Sharia serves as the primary legal source. In Saudi Arabia, Hudud laws prescribe specific punishments for crimes such as theft (amputation) or adultery (stoning), rooted in religious texts. While proponents argue this ensures moral consistency, critics highlight concerns over rigidity and human rights violations.

Governance structures also diverge significantly. Secular states typically operate under democratic or republican models, emphasizing citizen participation and representation. For example, Turkey, despite its Muslim-majority population, maintains a secular constitution that prioritizes civic law over religious authority. Islamic states, however, often adopt theocratic or hybrid models. Iran’s Islamic Republic, for instance, combines elected institutions with unelected religious bodies like the Guardian Council, which vets laws for compliance with Sharia. This dual structure can create tensions between popular sovereignty and religious authority.

Societal implications further illustrate the contrast. Secular states generally promote religious freedom and minority rights, as seen in India’s constitutional protections for diverse faiths. Islamic states, while often guaranteeing rights for Muslims, may impose restrictions on non-Muslims or dissenting voices. In Pakistan, blasphemy laws, rooted in Islamic principles, have been criticized for targeting religious minorities and stifling free expression. Yet, some Islamic states, like Malaysia, adopt more inclusive policies, blending Sharia with civil law to accommodate multicultural societies.

Ultimately, the debate between secularism and Islamic states reflects broader questions about the relationship between religion and power. Secular governance prioritizes neutrality and pluralism, appealing to diverse populations but risking detachment from cultural or religious identities. Islamic states, by integrating faith into politics, offer a sense of unity and purpose but risk exclusion or authoritarianism. The challenge lies in balancing religious principles with the demands of modern, diverse societies—a task neither model has fully resolved.

Why Political Uniforms Are Banned: Unraveling the Legal and Social Reasons

You may want to see also

Religion vs. Political Identity: Investigates when Muslim identity shifts from religious to political affiliation

In the complex interplay between faith and governance, the Muslim identity often transcends its religious boundaries, morphing into a political affiliation. This shift is not uniform; it occurs when religious tenets intersect with societal or state structures, creating a hybrid identity. For instance, in countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia, Islamic principles are enshrined in the constitution, blurring the line between personal faith and public policy. Here, being Muslim is not merely a spiritual choice but a civic duty, as adherence to Sharia law becomes a marker of political loyalty. This fusion of religion and statecraft exemplifies how Muslim identity can evolve from a private belief system into a public, political stance.

To understand this transition, consider the role of external pressures and internal mobilization. In regions where Muslims are minorities, such as in parts of Europe or India, political identity often emerges as a defensive mechanism. Discrimination or perceived threats to religious practices can galvanize communities, turning religious symbols like the hijab or calls to prayer into political statements. Conversely, in Muslim-majority nations, political parties often leverage religious rhetoric to consolidate power, framing opposition as heresy or disloyalty. This strategic use of religion in politics transforms faith into a tool for mobilization, shifting its role from spiritual guidance to political ideology.

A critical factor in this shift is the interpretation and application of Islamic principles in governance. For example, the concept of *ummah* (global Muslim community) can be invoked to foster unity but also to justify political alliances or conflicts. Similarly, the idea of *jihad* is often misconstrued in political discourse, stripped of its spiritual meaning and weaponized to advance agendas. Such manipulations highlight how religious doctrine, when politicized, loses its nuance and becomes a binary instrument for power struggles. This process is not inherent to Islam but reflects a broader pattern where religions are co-opted for political ends.

Practical steps to navigate this shift include fostering interfaith dialogue to demystify religious identities and promoting secular governance models that separate faith from state functions. For individuals, distinguishing between personal piety and political allegiance requires critical engagement with religious narratives. Communities can benefit from educational initiatives that teach the historical and contextual origins of religious texts, discouraging their misuse in political rhetoric. Ultimately, recognizing when Muslim identity becomes politicized is crucial for preserving the integrity of both religion and democracy, ensuring that faith remains a source of personal meaning rather than a pawn in power dynamics.

Who is RFK? Unveiling the Political Legacy of Robert F. Kennedy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Islam is primarily a religion based on faith, worship, and spiritual guidance. However, it also includes principles that address social, legal, and governance matters, which can influence political systems in some Muslim-majority countries.

No, Muslims hold diverse views. While some emphasize Islam’s role in governance and politics, others focus on its spiritual and personal aspects, separating it from political systems.

Yes, in some countries, there are political parties that advocate for Islamic principles in governance, such as Sharia law or Islamic statehood. These parties operate within the framework of their respective political systems.

Islam does not prescribe a single form of government. Historically, Muslim societies have adopted various systems, including monarchies, democracies, and theocratic models, depending on cultural and historical contexts.

Absolutely. Being Muslim is a matter of faith and practice, not necessarily political affiliation. Many Muslims do not align with Islamic political movements and focus instead on their personal and communal religious life.