The United States Constitution is the supreme law of the United States, and any laws enacted by Congress that conflict with it are unconstitutional and invalid. The Constitution outlines the rules and procedures that Congress must follow, including the legislative process for creating laws, the separation of powers, and the protection of individual rights and liberties. Despite this, there have been instances where acts of Congress have been deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, such as in the cases of United States v. Constantine and City of Boerne v. Flores. The Constitution also establishes the structure and powers of Congress, including the Senate and the House of Representatives, and imposes obligations on the President to report to Congress on the State of the Union. While Congress is responsible for creating and passing laws, the Constitution acts as a check to ensure that these laws do not violate the fundamental principles and rights outlined in the Constitution itself.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Congress decide not to fund the government? | Yes, but it would be politically devastating. |

| Can Congress be forced to follow its own rules? | No, the Supreme Court considers such cases non-justiciable. |

| Can Congress be impeached? | No, there is no process to impeach Congress. |

| Can Congress be held in contempt? | Possibly, but it is unclear. |

| Can Congress be forced to take action? | No, the Supreme Court cannot force Congress to take action. |

| Can Congress be forced to pass a budget? | No, but not passing a budget forces government shutdowns. |

| Can Congress be forced to act through elections? | Yes, representatives and a third of senators are elected every 2 years. |

| Can Congress be forced to act through the President? | Yes, the President can veto bills passed by Congress. |

| Can Congress be forced to act through the Constitution? | Yes, the Constitution grants Congress powers but does not oblige them to act. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Supreme Court cannot force Congress to act

The Constitution grants Congress powers to do things but does not generally obligate them to do any particular thing. It is constitutionally valid for Congress to pass a bill, vote a bill down, or decline to bring a bill up for a vote. The Constitution does not provide a process to impeach and remove Congress. The Supreme Court considers such cases to be non-justiciable on the grounds that they seek to answer a political question rather than a legal one. The Supreme Court is not granted any power by the Constitution to force the legislative branch to do anything. While the Court can answer legal questions—such as whether a law passed by the legislative branch violates the Constitution—it cannot order Congress to take a particular action.

The Constitution establishes the Supreme Court, but it permits Congress to decide how to organize it. The Judiciary Act of 1789 gave the Supreme Court original jurisdiction to issue writs of mandamus (legal orders compelling government officials to act in accordance with the law). However, the Supreme Court noted that the Constitution did not permit it to have original jurisdiction in this matter. Since Article VI of the Constitution establishes the Constitution as the supreme law of the land, an Act of Congress that is contrary to the Constitution cannot stand.

The Supreme Court's best-known power is judicial review, or the ability to declare a Legislative or Executive act in violation of the Constitution. While the Supreme Court can declare an Act of Congress unconstitutional, it cannot force Congress to act. The recourse for a failure by Congress to act is elections, where representatives and a third of senators are elected every two years.

While Congress must respect the separation of powers and decisional independence of the justices, it has long exercised its constitutional power to regulate ethics in the Supreme Court. Congress has the ultimate power to impeach and remove justices for bad behaviour.

The Constitution: Our Federal System's Foundation

You may want to see also

Congress can be held in contempt until it performs a required task

The Constitution grants Congress the authority to enact legislation and declare war, as well as the right to confirm or reject Presidential appointments. It also grants Congress the power to override a veto by the President with a two-thirds vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Constitution does not, however, oblige Congress to take any particular action. While Congress has the power to pass a bill, it is equally valid for it to vote a bill down, or to decline to bring a bill up for a vote.

Although the Constitution sets out rules for how Congress can operate, there is no process to impeach and remove Congress. If Congress fails to perform a task required by the Constitution, it is unclear what the remedy would be. One suggestion is that the Supreme Court could hold Congress in contempt until it performs the required task. However, the Supreme Court considers such cases non-justiciable, believing they seek to answer a political question rather than a legal one. The Supreme Court does not have the power to force the legislative branch to take action.

The recourse for a failure by Congress to act is elections. Representatives and a third of Senators are elected every two years, and voters are free to apportion blame as they see fit. While Congress can decide not to fund the government, this would be politically devastating. Therefore, compromise is usually found, and a budget is passed.

In conclusion, while there is no clear mechanism to hold Congress in contempt for failing to perform a required task, the Supreme Court could potentially do so. However, the more likely recourse for congressional inaction is political and electoral consequences.

Holmes' Constitutional Legacy: Save or Rewrite?

You may want to see also

Congress can override a presidential veto with a two-thirds majority

The US Constitution sets down rules for how Congress can operate, and what it may, may not, or must do. The Constitution grants Congress powers to do things but does not generally obligate them to do any particular thing. Constitutionally, it is equally valid for Congress to pass a bill, to vote a bill down, or to decline to bring a bill up for a vote.

Congress and the President have a system of checks and balances in place, where they can each take steps to prevent the other from acting unilaterally. For example, the President can veto a bill passed by Congress, but Congress can override this veto with a two-thirds majority. This is a significant event and has only occurred around 110 times in history.

The process of legislation usually involves Congress knowing the President's opinion on any major piece of legislation, and the President knowing how much support a bill has in Congress. If a bill has enough support to override a veto, Congress may choose to do so, and the President may not bother to veto the bill in the first place. However, going through the motions of passing a bill, having it vetoed, and then overriding the veto is a way of demonstrating unity against the President.

While the Supreme Court can hold a law passed by Congress to be unconstitutional, it does not have the power to force Congress to act. If Congress fails to do something required by the Constitution, there is no process to impeach and remove Congress.

The Preamble: Our Government's Founding Principles

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Congress can decline to bring a bill up for a vote

The Constitution grants Congress powers to act, but it does not generally obligate them to do any particular thing. Congress has the freedom to choose what it wants to prioritize. It is constitutionally valid for Congress to decline to bring a bill up for a vote, just as it is valid for them to pass or vote down a bill.

The Constitution authorizes each House to determine the rules of its proceedings. The House of Representatives adopts its rules anew each Congress, typically on the opening day of the first session. The Senate, on the other hand, operates under continuous standing rules that it amends from time to time.

The Senate must first agree to bring a bill to the floor, either by agreeing to a unanimous consent request or by voting to adopt a motion to proceed with the bill. Senators can then propose amendments. However, there are no debate limits in the Senate, and a simple numerical majority cannot impose a debate limit or move to a final vote. This means that Senators can threaten or engage in a filibuster, which can delay or prevent a final vote.

The filibuster has been criticized for causing congressional stagnation and pushing presidents to increase their use of executive power. Some legal scholars argue that it may not be constitutional, citing Article I, Section 5, which states that "a majority of each House shall constitute a quorum to do business." There have been calls to eliminate the filibuster, but this would require a two-thirds supermajority or the use of the "'nuclear option,' where the Senate majority leader uses a non-debatable motion to bring a bill to a vote.

Constitutional Linguistics: National Languages in Law

You may want to see also

Congress has sole authority to enact legislation and declare war

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to enact legislation and declare war. The Constitution sets down rules for how Congress can operate, and what it may, may not, or must do. Congress has equal legislative functions and powers, with certain exceptions. For example, the Constitution provides that only the House of Representatives may originate revenue bills.

The Constitution also grants Congress the authority to "'make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the Land and Naval Forces', as well as to control the funding of those forces. This is in contrast to the Executive, which has inherent authority as Commander-in-Chief. The President, as Commander-in-Chief, has the power to direct the military after a Congressional declaration of war.

The War Powers Resolution (WPR) was enacted in 1973 to mitigate disputes between Congress and the President over war powers. The WPR requires the President to report to Congress within 48 hours of committing troops and to remove all troops after 60 days if Congress has not granted an extension. However, the WPR has not effectively addressed the separation of war powers between Congress and the President, with Presidents interpreting statutory authorizations broadly and Congress being reluctant to seek their repeal.

Despite the WPR, Presidents have engaged in military operations without express Congressional consent, including the Korean War, the Vietnam War, Operation Desert Storm, the Afghanistan War of 2001, and the Iraq War of 2002. These operations are not considered official wars by the United States due to the lack of a formal Congressional declaration of war.

While the Constitution grants Congress powers to act, it generally does not obligate Congress to take any specific actions. Legally, Congress could decide not to fund the government for as long as it wants. However, the political consequences of such inaction could be devastating. The recourse for Congress's failure to act is through elections, as representatives and a third of senators are elected every two years.

The Goldilocks Zone: Life's Sweet Spot Around Stars

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Supreme Court of the United States has the power to hold Acts of Congress unconstitutional in whole or in part.

No. All legislative powers are vested in Congress, which consists of a Senate and House of Representatives.

The Constitution outlines the rules and responsibilities of Congress, including the power to make laws, declare war, and raise and support armies. It also establishes the structure of Congress, such as the requirement for each state to have Representatives in the House based on their population.

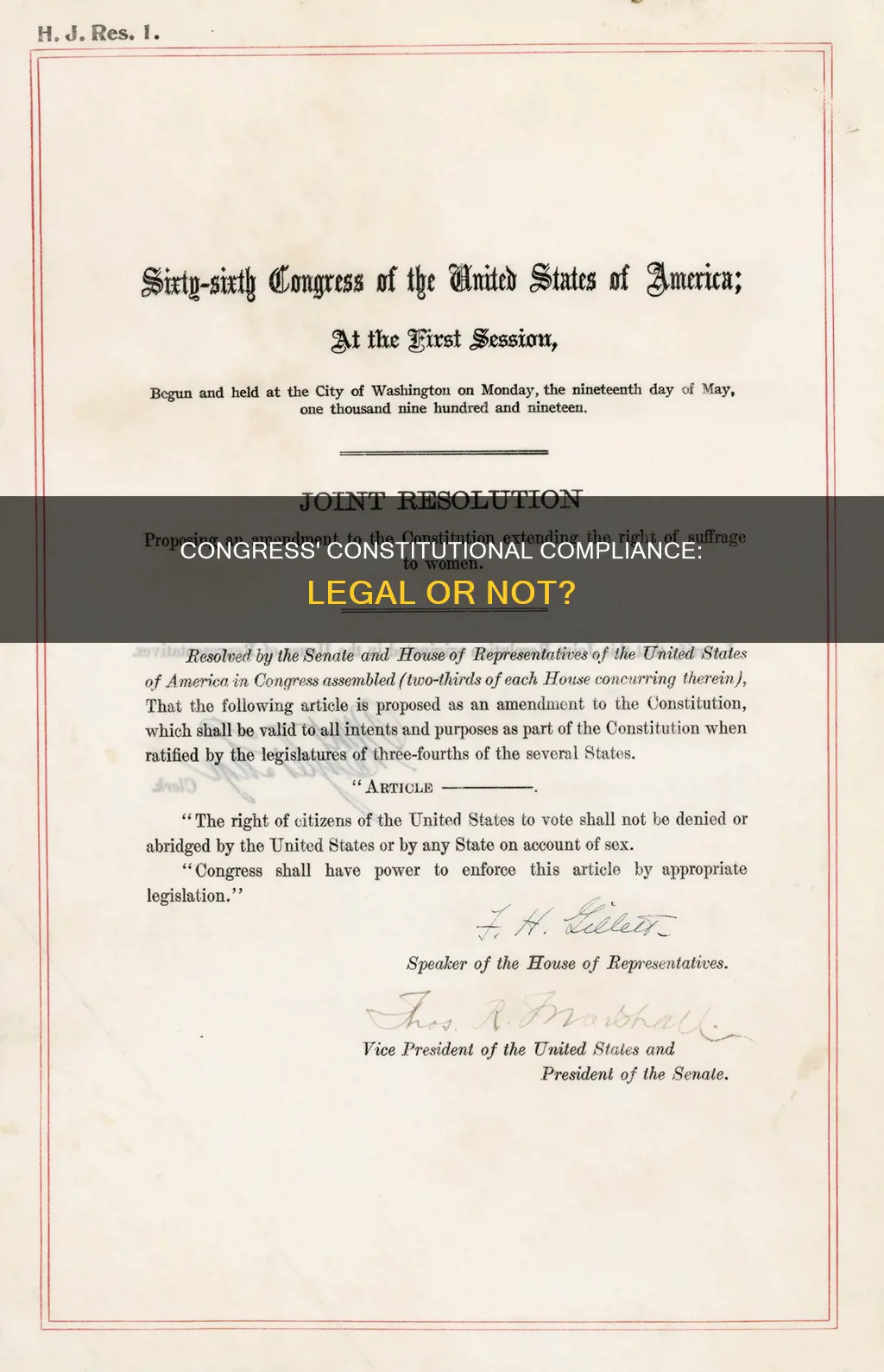

Congress can propose amendments to the Constitution, but these amendments must be approved by a two-thirds majority in both the House and the Senate. Amendments do not require the President's approval.

![Constitutional Law: [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61R-n2y0Q8L._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Constitutional Law [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61qrQ6YZVOL._AC_UY218_.jpg)