The question of whether impeachment is inherently a political question has long sparked debate among legal scholars, historians, and policymakers. At its core, impeachment is a constitutional process designed to hold public officials, particularly the President, accountable for treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors. However, the ambiguity of these terms and the lack of clear legal standards often blur the line between legal and political considerations. Critics argue that impeachment proceedings are inevitably influenced by partisan interests, public opinion, and the balance of power in Congress, making them more of a political tool than a strictly legal mechanism. Proponents, on the other hand, contend that while politics may play a role, the process remains grounded in constitutional principles and serves as a vital check on executive power. This tension raises fundamental questions about the nature of impeachment, its legitimacy, and its role in democratic governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nature of Impeachment | A quasi-judicial process outlined in Article I, Section 2 and 3 of the U.S. Constitution, but with political implications. |

| Role of Congress | The House of Representatives (political body) initiates impeachment, while the Senate (political body) conducts the trial, blending legal and political considerations. |

| Criteria for Impeachment | "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors" – a vague standard open to political interpretation. |

| Judicial Review | Limited; courts generally consider impeachment a non-justiciable political question under the political question doctrine (e.g., Nixon v. United States, 1993). |

| Party Influence | Highly partisan; impeachment proceedings often reflect the political composition and priorities of Congress. |

| Public Opinion | Significantly impacts the political calculus of impeachment, influencing lawmakers' decisions. |

| Historical Precedents | Past impeachments (e.g., Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, Donald Trump) highlight the political nature of the process, often tied to party control and public sentiment. |

| Executive Power | Impeachment serves as a political check on the executive branch, balancing power between branches of government. |

| International Perspective | In other democracies, impeachment-like processes are often similarly politicized, reflecting broader political dynamics. |

| Constitutional Ambiguity | The Constitution does not provide clear guidelines for what constitutes an impeachable offense, leaving room for political interpretation. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical Context of Impeachment

Impeachment, as a constitutional mechanism, has roots deeply embedded in English common law, where it was used to address misconduct by crown officials. The framers of the U.S. Constitution adopted this concept, embedding it in Article II, Section 4, as a check on executive and judicial power. Historically, impeachment was designed not merely as a legal tool but as a political safeguard to protect the republic from abuse of authority. Its origins reflect a pragmatic balance between law and politics, ensuring that leaders could be held accountable without destabilizing governance.

The first impeachment trial in U.S. history, that of Senator William Blount in 1797, set an early precedent for the political nature of the process. Blount was accused of conspiring with Britain to seize Spanish-controlled Louisiana, but the Senate dismissed the case, arguing that a senator was not a "civil officer" subject to impeachment. This case underscored the ambiguity of impeachment's scope and its susceptibility to political interpretation. It also highlighted how partisan interests could influence the process, as Blount’s expulsion from the Senate was a political act rather than a strictly legal one.

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson in 1868 further blurred the lines between law and politics. Johnson, a Democrat succeeding Abraham Lincoln, clashed with the Republican-dominated Congress over Reconstruction policies. His impeachment, driven by the Tenure of Office Act, was as much about policy disagreements as it was about alleged constitutional violations. Johnson’s acquittal by a single vote demonstrated how impeachment could become a tool for political retribution rather than a neutral legal proceeding. This case remains a cautionary tale about the dangers of weaponizing impeachment for partisan gain.

In contrast, the impeachment proceedings against Richard Nixon in 1974 and Bill Clinton in 1998 reveal how public opinion and political climate shape outcomes. Nixon’s resignation amid the Watergate scandal was precipitated by overwhelming bipartisan consensus and public outrage, while Clinton’s acquittal reflected partisan divisions and public skepticism about the severity of the charges. These cases illustrate that impeachment is not confined to legal technicalities but is deeply influenced by the political environment, media narratives, and public sentiment.

Historically, impeachment has functioned as both a legal and political instrument, its application shaped by the era’s power dynamics and societal values. While the Constitution provides a framework, the process has consistently been interpreted through a political lens, reflecting the complexities of governance and the interplay between law and power. Understanding this history is crucial for navigating contemporary debates about impeachment, as it underscores the inevitability of political considerations in what is ostensibly a legal mechanism.

Ecuador's Political Stability: Analyzing Current Climate and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Role of Political Parties in Impeachment

Impeachment, as a constitutional process, is inherently intertwined with the dynamics of political parties, often blurring the lines between legal accountability and partisan interests. The role of political parties in impeachment proceedings is not merely peripheral; it is central to how the process unfolds, from the initiation of charges to the final vote. Parties act as both catalysts and gatekeepers, leveraging their influence to shape public perception, rally legislative support, and ultimately determine the outcome. This partisan involvement raises critical questions about the objectivity of impeachment, transforming it from a strictly legal mechanism into a political battleground.

Consider the strategic calculus parties employ when deciding whether to pursue impeachment. The decision is rarely driven solely by the severity of alleged misconduct; instead, it hinges on political expediency, electoral calculations, and the potential for public backlash. For instance, the impeachment of a president from an opposing party is often framed as a moral imperative, while similar allegations against a member of one’s own party may be downplayed or ignored. This double standard underscores how parties use impeachment as a tool to weaken political adversaries and consolidate power, rather than as a neutral means of upholding constitutional integrity.

The partisan nature of impeachment is further evident in the legislative process itself. In the U.S., the House of Representatives, controlled by the majority party, holds the power to bring impeachment charges, while the Senate, often equally divided along party lines, conducts the trial. Party loyalty frequently dictates voting behavior, with members adhering to their caucus’s position regardless of the evidence presented. This tribalism diminishes the credibility of impeachment as a fair and impartial process, reducing it to a spectacle of party versus party rather than a solemn duty to protect the nation’s interests.

To mitigate the partisan hijacking of impeachment, reforms could be considered to depoliticize the process. One proposal is the establishment of an independent bipartisan commission to evaluate impeachment charges, ensuring that decisions are based on merit rather than party allegiance. Another approach could involve stricter constitutional criteria for impeachment, limiting its use to the most egregious offenses and reducing its appeal as a political weapon. Such measures, while not foolproof, could restore public trust in impeachment as a legitimate check on executive power.

Ultimately, the role of political parties in impeachment highlights a paradox: while parties are essential to the functioning of democratic institutions, their dominance in this process risks undermining its legitimacy. Impeachment, at its core, is intended to safeguard the rule of law, but when it becomes a vehicle for partisan warfare, it loses its moral authority. Recognizing this tension is crucial for anyone seeking to understand or reform the impeachment process, as it reveals the delicate balance between political pragmatism and constitutional fidelity.

Bridging Divides: Effective Strategies to Resolve Political Conflict Peacefully

You may want to see also

Judicial Review and Impeachment

Impeachment, as a constitutional mechanism, inherently blurs the lines between law and politics, raising questions about the role of judicial review in this process. The U.S. Supreme Court has historically been cautious in asserting jurisdiction over impeachment proceedings, often citing the "political question doctrine." This doctrine holds that certain issues are inherently political and thus non-justiciable, meaning they are beyond the scope of judicial review. In *Nixon v. United States* (1993), the Court declined to intervene in a Senate impeachment trial, ruling that the procedures and outcomes of impeachment are entrusted to Congress and are not subject to judicial oversight. This decision underscores the principle that impeachment is fundamentally a political process, not a legal one, even though it operates within a constitutional framework.

Analyzing the interplay between judicial review and impeachment reveals a delicate balance of power. The Constitution grants the House of Representatives the sole power to impeach and the Senate the sole power to try impeachments, leaving little room for judicial intervention. However, the judiciary retains the authority to interpret the Constitution, which could theoretically extend to evaluating whether impeachment proceedings adhere to constitutional standards. For instance, if an impeachment were based on criteria outside the constitutional definition of "high crimes and misdemeanors," a court might argue that such an action violates the Constitution. Yet, the political question doctrine has consistently limited the judiciary’s willingness to engage in such reviews, emphasizing that the political branches must resolve disputes arising from impeachment.

A comparative perspective highlights how other democracies handle similar dilemmas. In countries like Brazil and South Korea, courts have played a more active role in reviewing impeachment processes, sometimes invalidating proceedings deemed unconstitutional. These examples suggest that judicial review of impeachment is not universally off-limits, but rather depends on a nation’s constitutional design and judicial philosophy. In the U.S., however, the tradition of deference to the political branches in impeachment matters remains strong, reflecting a commitment to separation of powers and the avoidance of judicial overreach.

Practically, this means that individuals and organizations seeking to challenge an impeachment must navigate a narrow path. While constitutional violations in the impeachment process could theoretically be grounds for judicial intervention, the political question doctrine erects a high barrier. Advocates must frame their arguments in a way that demonstrates a clear constitutional violation, rather than merely contesting the political judgment of Congress. For example, a challenge based on denial of due process in the Senate trial might have a stronger footing than one disputing the sufficiency of the evidence presented by the House.

In conclusion, the relationship between judicial review and impeachment is defined by restraint and deference. While the judiciary retains the theoretical authority to review constitutional questions arising from impeachment, the political question doctrine has effectively shielded most aspects of the process from judicial scrutiny. This dynamic reinforces the political nature of impeachment, ensuring that it remains a tool of the legislative branch, not the courts. For those engaged in or affected by impeachment proceedings, understanding these boundaries is crucial for strategizing effectively within the constitutional framework.

Is Black Lives Matter Political? Exploring the Movement's Impact and Intent

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Public Opinion vs. Legal Grounds

Impeachment proceedings often hinge on a delicate balance between public sentiment and constitutional criteria, yet these two forces rarely align seamlessly. Public opinion, shaped by media narratives and partisan loyalties, tends to fluctuate with the political climate, demanding swift accountability or staunch defense based on ideological leanings. Legal grounds, however, are tethered to the Constitution’s narrow definition of "high crimes and misdemeanors," requiring concrete evidence of abuse of power, bribery, or obstruction of justice. This divergence becomes stark when public outrage outpaces provable offenses, as seen in the 2019 impeachment of President Trump, where 85% of Democrats supported removal compared to only 8% of Republicans, despite a lack of bipartisan consensus on legal culpability.

Consider the role of timing and strategy in navigating this tension. Politicians often frame impeachment as a referendum on leadership rather than a judicial process, leveraging public opinion to pressure lawmakers. For instance, during the Watergate scandal, public approval for Nixon’s removal surged to 57% only after the release of the "smoking gun" tape, aligning public sentiment with irrefutable evidence. In contrast, the 1998 Clinton impeachment saw public opinion largely reject the proceedings, with 60% opposing removal, viewing the charges as politically motivated. These examples underscore the importance of synchronizing legal arguments with public perception to avoid accusations of partisanship.

To bridge the gap between public opinion and legal grounds, lawmakers must adopt a dual-pronged approach. First, transparency is critical; releasing unredacted evidence and holding public hearings can educate the populace while bolstering the legitimacy of the process. Second, framing matters—articulating how legal violations also betray public trust can resonate with both legal purists and emotionally invested citizens. For instance, emphasizing that obstruction of justice undermines democratic institutions can appeal to both constitutional scholars and voters concerned about accountability.

However, caution is warranted. Over-reliance on public opinion risks reducing impeachment to a popularity contest, while strict adherence to legal grounds can appear tone-deaf to widespread grievances. The 2021 second impeachment of President Trump illustrates this dilemma: while 52% of Americans supported removal, the Senate’s 57-43 vote fell short of the two-thirds majority, highlighting the challenge of reconciling public demand with procedural hurdles. Striking this balance requires not just legal acumen but also political sensitivity, recognizing that impeachment is both a constitutional mechanism and a barometer of societal values.

Ultimately, the interplay between public opinion and legal grounds transforms impeachment into a dynamic, rather than static, process. It demands that lawmakers act as both jurists and representatives, weighing evidence while acknowledging the electorate’s voice. As history shows, impeachments that fail to harmonize these elements risk being dismissed as either witch hunts or whitewashes. By treating public sentiment as a compass rather than a mandate, and legal criteria as a foundation rather than a constraint, the process can retain its integrity while reflecting the nation’s collective conscience.

Mastering Political Banter: Crafting Witty, Sharp, and Engaging Dialogue

You may want to see also

Impeachment as a Partisan Tool

Impeachment, theoretically a constitutional check on executive power, has increasingly become a weapon in the partisan arsenal. This transformation is evident in the frequency and tone of impeachment discussions, which now align more with political expediency than with the gravity of constitutional crisis. The shift raises critical questions about the integrity of the process and its long-term implications for governance.

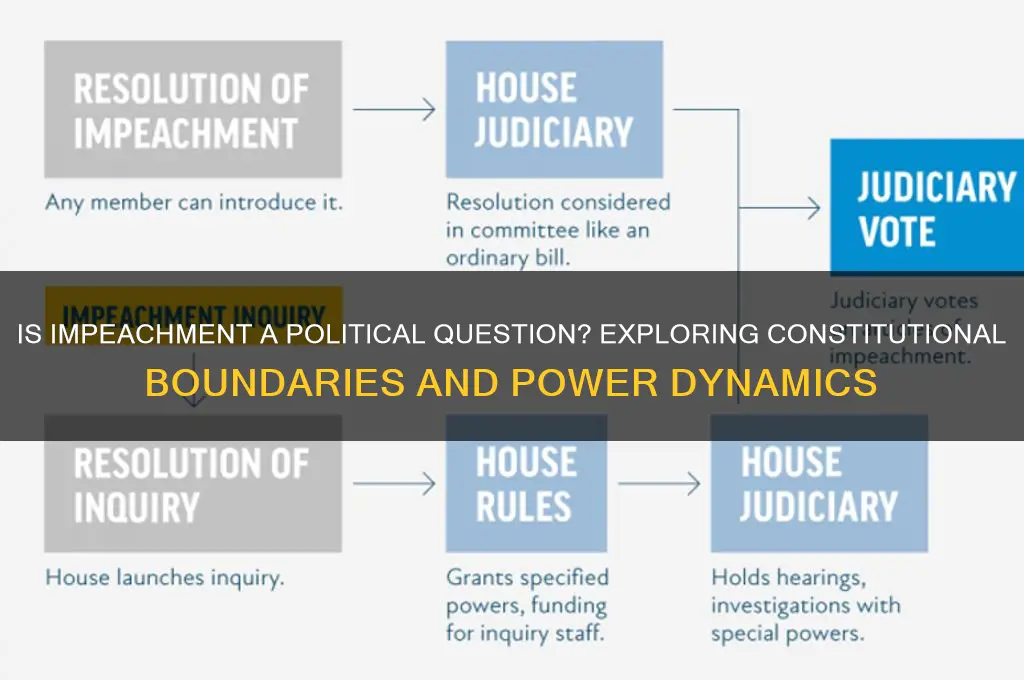

Consider the procedural mechanics of impeachment. While the Constitution outlines a clear framework—the House impeaches, the Senate tries—the execution has become a masterclass in political theater. Parties leverage procedural rules to delay, obfuscate, or expedite the process based on their strategic goals. For instance, the timing of an impeachment vote is often calculated to maximize political damage or to coincide with election cycles, rather than to address urgent misconduct. This manipulation of procedure underscores how impeachment has been co-opted as a tool for partisan gain.

Historical examples illustrate this trend. The impeachment of Bill Clinton in 1998 and Donald Trump in 2019 and 2021 highlight how the process has been weaponized to settle political scores. In Clinton’s case, the Republican-controlled House pursued impeachment over a personal scandal, while the Senate, with a slim Republican majority, acquitted him. Trump’s impeachments, conversely, were driven by a Democratic House and met with partisan resistance in the Senate. These cases demonstrate how impeachment has shifted from a rare, solemn duty to a predictable outcome of political polarization.

To mitigate the partisan misuse of impeachment, structural reforms could be considered. One proposal is to introduce a bipartisan commission to evaluate impeachment charges before they proceed to a vote, ensuring a baseline of legitimacy. Another is to require a supermajority in the House to initiate impeachment, raising the threshold for such a serious action. While these measures may face political resistance, they offer a pathway to restoring impeachment’s constitutional intent.

Ultimately, the partisan weaponization of impeachment erodes public trust in democratic institutions. When impeachment becomes just another tool in the political toolbox, its power to hold leaders accountable is diminished. Recognizing this trend is the first step toward reclaiming impeachment as a safeguard of the Constitution, rather than a vehicle for political retribution.

Brussels' Political Stability: A Comprehensive Analysis of Current Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, impeachment is inherently political because it involves elected officials making judgments based on constitutional standards, public opinion, and partisan considerations rather than purely legal criteria.

Courts often view impeachment as a political question because the Constitution assigns the process to the legislative branch, and judicial review of such decisions would interfere with the separation of powers.

Generally, no. Impeachment is considered a non-justiciable political question, meaning courts will not intervene in the process or its outcomes.

Yes, partisanship often influences impeachment proceedings, as lawmakers may vote along party lines rather than strictly on the merits of the case, reinforcing its political nature.

The Constitution sets the standard for impeachment as "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors," but the interpretation of these terms is left to Congress, making the process largely political rather than strictly legal.