Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries to favor a particular political party or group, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. At its core, the question of whether gerrymandering constitutes a political question hinges on whether it is an issue that courts should address or one that falls solely within the purview of the legislative and executive branches. Proponents argue that redistricting is inherently a political process, best left to elected officials, while critics contend that extreme gerrymandering undermines democratic principles and warrants judicial intervention. This debate raises fundamental questions about the separation of powers, the role of the judiciary in safeguarding fair elections, and the limits of political self-interest in shaping electoral outcomes. As courts grapple with challenges to gerrymandered maps, the resolution of this issue will have profound implications for the future of American democracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Gerrymandering is the practice of manipulating political boundaries to favor one party or class, often considered a political question due to its impact on electoral outcomes. |

| Legal Status | In the U.S., the Supreme Court has ruled that some gerrymandering claims are non-justiciable political questions (e.g., Rucho v. Common Cause, 2019), while others (like racial gerrymandering) remain subject to judicial review. |

| Political Nature | Involves partisan interests, as redistricting is typically controlled by state legislatures, often leading to accusations of bias and strategic manipulation. |

| Judicial Role | Courts struggle to define neutral standards for partisan gerrymandering, leading to debates over whether it is a matter for legislative or political resolution rather than judicial intervention. |

| Public Perception | Widely viewed as a political tactic to secure electoral advantages, sparking public debate and reform efforts (e.g., independent redistricting commissions). |

| Historical Context | Historically tied to political power struggles, with both major U.S. parties engaging in gerrymandering when in control of redistricting processes. |

| Reform Efforts | Political solutions, such as ballot initiatives and state-level reforms, are often pursued due to the judicial reluctance to intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases. |

| International Perspective | In countries with independent redistricting bodies, gerrymandering is less prevalent, highlighting its political nature in systems with partisan control. |

Explore related products

$45 $90

What You'll Learn

Definition and Legal Context

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage, is a contentious issue that often blurs the line between politics and law. At its core, gerrymandering involves redrawing district lines to favor a particular political party or group, diluting the voting power of opponents. While the term itself dates back to the early 19th century, its modern legal context is shaped by a complex interplay of constitutional principles, judicial interpretations, and legislative actions. Understanding its definition and legal framework is essential to addressing whether gerrymandering constitutes a political question or a judicially resolvable issue.

Legally, gerrymandering challenges often hinge on violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and the First Amendment’s freedom of association. The Supreme Court has grappled with whether partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable, meaning whether courts can adjudicate them or if they fall into the realm of political questions reserved for legislative branches. In *Vieth v. Jubelirer* (2004), the Court was divided, with no clear majority emerging on a manageable standard for evaluating such claims. However, in *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), the Court punted on the issue, ruling on procedural grounds without resolving the justiciability question. This ambiguity leaves the legal landscape unsettled, with lower courts and state legislatures navigating the issue in varying ways.

To assess whether gerrymandering is a political question, one must consider the criteria established in *Baker v. Carr* (1962), which outlines factors such as the lack of judicially discoverable standards and the inappropriateness of judicial intervention. Partisan gerrymandering claims often fail the first criterion because courts struggle to define a clear, neutral standard for determining when political line-drawing crosses into unconstitutional territory. For instance, metrics like the efficiency gap, which measures "wasted votes," have been proposed but remain controversial. Without a universally accepted standard, courts risk becoming entangled in inherently political decisions, raising concerns about judicial overreach.

Practically, the legal context of gerrymandering varies by state. Some states, like California and Arizona, have established independent redistricting commissions to minimize partisan influence. Others rely on legislative processes, often dominated by the party in power. This patchwork approach underscores the tension between political control and legal oversight. For individuals or groups challenging gerrymandering, the first step is to identify the specific legal grounds for the claim, whether based on federal constitutional principles or state laws. Engaging with local advocacy groups and legal experts can provide tailored strategies for addressing gerrymandering in a given jurisdiction.

In conclusion, the definition and legal context of gerrymandering reveal a practice deeply rooted in politics but subject to constitutional scrutiny. While the Supreme Court has yet to provide a definitive answer on its justiciability, the ongoing debate highlights the need for clear standards and mechanisms to balance political power with legal accountability. Whether gerrymandering is a political question or a judicial matter remains unresolved, but its impact on democratic representation demands continued attention and action.

Understanding Barry Goldwater's Political Classification: Conservative Icon or Extremist?

You may want to see also

Historical Examples and Impact

Gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating electoral boundaries for political advantage, has left an indelible mark on history, often with far-reaching consequences. One of the earliest and most notorious examples dates back to 1812 in Massachusetts, where Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a redistricting plan that created a district resembling a salamander, hence the term "gerrymander." This maneuver aimed to favor his Democratic-Republican Party, demonstrating how political cartography can be wielded as a weapon to entrench power. The impact? Gerry's opponents coined the term in protest, but the practice persisted, setting a precedent for future political manipulation.

Consider the 1960s and 1970s, when the civil rights movement brought gerrymandering into sharper focus. In the South, white politicians often drew district lines to dilute the voting power of African Americans, despite the Voting Rights Act of 1965. For instance, in Georgia, legislators crafted districts that fragmented Black communities, ensuring white majorities in most districts. This systematic disenfranchisement highlights how gerrymandering can undermine democratic principles, perpetuating racial inequality and stifling political representation for marginalized groups.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and gerrymandering remains a contentious issue. In 2004, Pennsylvania’s 7th congressional district became a poster child for extreme gerrymandering, with its boundaries so convoluted that it was dubbed "Goofy kicking Donald Duck." This district was engineered to favor Republicans, showcasing how modern technology and data analytics have supercharged the practice. The impact? A single party can dominate elections despite not necessarily representing the majority will, raising questions about the legitimacy of electoral outcomes.

To combat these historical abuses, courts and activists have pushed for reforms. In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in *Rucho v. Common Cause* that federal courts cannot address partisan gerrymandering claims, leaving the issue to state legislatures and voters. However, states like California and Michigan have adopted independent redistricting commissions, reducing political influence in the process. These reforms offer a path forward, but their success depends on widespread adoption and vigilance against backsliding.

The historical examples of gerrymandering reveal a recurring theme: it is a tool of power, often used to entrench one group at the expense of another. From its origins in early 19th-century America to its modern manifestations, gerrymandering has distorted representation, undermined democracy, and exacerbated social divisions. While reforms offer hope, the question remains: can we disentangle politics from the process entirely, or is gerrymandering inherently a political question, resistant to impartial solutions? The answer may lie in sustained public pressure and innovative institutional design.

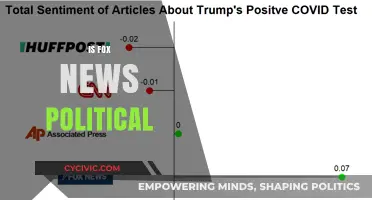

COVID-19: A Public Health Crisis or Political Tool?

You may want to see also

Supreme Court Rulings

The Supreme Court's engagement with gerrymandering has been marked by a delicate balance between judicial authority and deference to political processes. In *Vieth v. Jubelirer* (2004), the Court grappled with whether partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable, ultimately producing a plurality opinion that lacked a clear standard. Justice Scalia argued that such claims were inherently political and thus nonjusticiable, while Justice Kennedy suggested a manageable standard might exist but did not define one. This decision left lower courts and litigants in limbo, highlighting the Court's struggle to delineate its role in policing political mapmaking.

A shift occurred in *Gill v. Whitford* (2018), where the Court sidestepped the core issue of whether Wisconsin's redistricting plan was unconstitutional, instead ruling that the plaintiffs lacked standing. The Court demanded a more precise showing of harm, requiring plaintiffs to demonstrate that their individual votes were diluted in their specific districts. While this decision did not resolve the justiciability question, it imposed stricter procedural hurdles for gerrymandering challenges, effectively narrowing the pathway for future litigation.

In *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), the Court decisively ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims present a nonjusticiable political question, leaving the issue to Congress and state legislatures. Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion emphasized the lack of judicially manageable standards and the risk of the Court appearing partisan. This decision effectively closed the federal courthouse doors to partisan gerrymandering challenges, shifting the battleground to state courts and legislative reforms.

Despite these rulings, the Court has not entirely abandoned the field. In *Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission* (2015), the Court upheld the use of independent commissions for redistricting, affirming that states have the authority to remove mapmaking from legislators’ hands. This decision offered a pragmatic alternative to judicial intervention, suggesting that solutions to gerrymandering may lie in structural reforms rather than federal litigation.

Taken together, the Court’s rulings reflect a cautious approach to gerrymandering, prioritizing judicial restraint over expansive intervention. While federal remedies remain limited, the decisions underscore the importance of state-level initiatives and legislative action. For advocates and reformers, the takeaway is clear: the fight against gerrymandering must now focus on grassroots efforts, constitutional amendments, and the creation of independent redistricting bodies.

Expectant Mother or Pregnant Person: Navigating Politically Correct Language

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Partisan vs. Nonpartisan Redistricting

Gerrymandering, the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. At the heart of this debate lies the question of who should be responsible for redistricting: partisan legislators or nonpartisan commissions. The choice between these two approaches has profound implications for the fairness and integrity of elections.

Partisan redistricting, where state legislators control the process, often results in maps that prioritize political advantage over equitable representation. For instance, in North Carolina, Republican-led redistricting in 2016 created districts so heavily skewed in their favor that courts later deemed them unconstitutional. This approach allows the party in power to entrench its dominance, effectively choosing its voters rather than the other way around. Critics argue that this undermines democratic principles, as it can dilute the voting power of minority groups and create uncompetitive elections.

In contrast, nonpartisan redistricting seeks to remove political self-interest from the process. States like California and Arizona have established independent commissions composed of citizens, often selected through a bipartisan or nonpartisan process, to draw district lines. These commissions are typically required to adhere to criteria such as compactness, contiguity, and respect for communities of interest, rather than partisan advantage. For example, California’s 2020 redistricting process, overseen by a 14-member commission, resulted in maps that reflected demographic changes without overt political bias. This approach is championed as a way to restore public trust in the electoral system and ensure that districts are drawn fairly.

However, nonpartisan redistricting is not without challenges. Critics argue that it can be difficult to entirely eliminate political influence, as commissioners may still bring implicit biases to the table. Additionally, the process can be resource-intensive and time-consuming, requiring significant public engagement and transparency. Despite these hurdles, proponents maintain that the benefits of reducing partisan manipulation outweigh the costs.

For states considering reform, the choice between partisan and nonpartisan redistricting hinges on their commitment to fairness and accountability. Partisan control offers efficiency and alignment with legislative priorities but risks perpetuating political inequality. Nonpartisan commissions, while more complex, promise a more equitable and transparent process. Ultimately, the decision reflects a state’s values: whether to prioritize political power or the principles of representative democracy.

Fashion's Political Threads: Unraveling Style's Silent Power and Influence

You may want to see also

Public Perception and Reform Efforts

Public perception of gerrymandering often hinges on its visibility and impact on local communities. When district maps are redrawn in ways that clearly favor one party, voters notice. For instance, in North Carolina, a 2019 court ruling struck down congressional maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders, highlighting how extreme redistricting can alienate voters and erode trust in the electoral process. This visibility fuels public outrage, making gerrymandering a tangible issue rather than an abstract political concept.

Reform efforts have taken various forms, with independent redistricting commissions emerging as a popular solution. States like California and Arizona have established such commissions to remove partisan influence from the map-drawing process. These commissions typically include a mix of Democrats, Republicans, and unaffiliated voters, ensuring a balanced approach. However, their effectiveness depends on strict guidelines and transparency. For example, California’s commission holds public hearings and accepts community input, fostering trust and accountability. Critics argue that even these commissions can be influenced by political pressures, but they remain a significant step toward fairness.

Public education plays a critical role in driving reform. Organizations like the League of Women Voters and the Brennan Center for Justice have launched campaigns to inform voters about gerrymandering’s effects on representation. These efforts often include interactive tools, such as map-drawing simulations, to help citizens understand how districts are manipulated. By demystifying the process, these initiatives empower voters to advocate for change. For instance, in Michigan, a grassroots campaign led to a 2018 ballot initiative that established an independent redistricting commission, demonstrating the power of informed public action.

Despite progress, reform faces significant challenges. Partisan resistance remains a major obstacle, as those in power often benefit from the status quo. In states like Texas and Ohio, efforts to curb gerrymandering have been met with legal battles and legislative roadblocks. Additionally, the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* declared that federal courts cannot address partisan gerrymandering, leaving reform largely to state-level initiatives. This decision underscores the need for sustained public pressure and creative solutions, such as leveraging technology to analyze and challenge unfair maps.

Ultimately, public perception and reform efforts are intertwined in the fight against gerrymandering. As voters become more aware of its impact, they demand accountability and fairness. While challenges persist, the combination of independent commissions, public education, and grassroots advocacy offers a path forward. Success depends on continued vigilance and innovation, ensuring that the democratic principle of "one person, one vote" remains intact.

Is Apple News Politically Biased? Analyzing Its Editorial Slant and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, gerrymandering is often considered a political question because it involves the drawing of electoral district boundaries, which is typically controlled by the political party in power.

While gerrymandering is inherently political, courts can intervene in cases where it violates constitutional or legal standards, such as equal protection or voting rights.

Gerrymandering is seen as a political question because it involves partisan interests and the exercise of legislative power, making it difficult to establish neutral, judicially manageable standards.

The Supreme Court has historically struggled with gerrymandering cases, often ruling that some claims are nonjusticiable political questions, though it has allowed challenges based on racial gerrymandering.