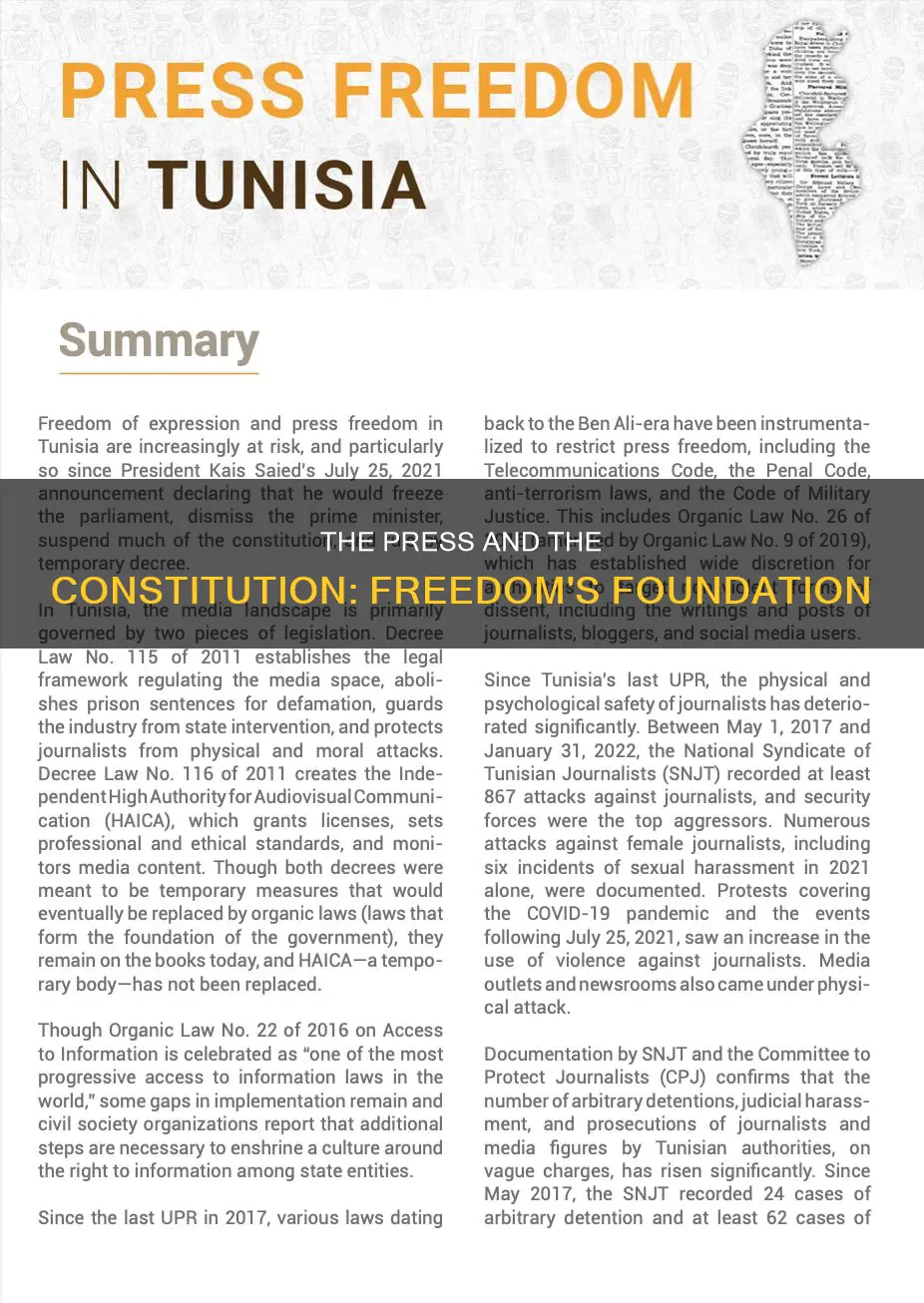

Freedom of the press is a concept that has been much debated, with the question often arising as to whether the institutional press is entitled to greater freedom from government regulations or restrictions than non-press individuals or groups. The First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States is clear that Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. This has been interpreted in various ways by the Supreme Court, which has refused to grant increased First Amendment protection to institutional media over other speakers. The Court has also suggested that the press is protected to promote and protect the exercise of free speech in society at large, including people's interest in receiving information.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Freedom of the press in the U.S. Constitution | Protected by the First Amendment |

| Freedom to publish | Guaranteed by the Constitution |

| Freedom of speech | Protected by the First Amendment |

| Freedom from government restraint | Not explicitly granted to the press |

| Protection from defamation lawsuits | Not guaranteed by the First Amendment |

| Protection from antitrust laws | Not guaranteed by the First Amendment |

| Right to gather information | Recognized by the Court |

| Right to access information | Not guaranteed by the First Amendment |

| Press freedom ranking | 42nd in the world in 2022 |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Freedom of the press as a limitation on government regulation

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects freedom of the press, alongside freedom of speech and religion. This amendment acts as a limitation on government regulation, preventing Congress from making any law that abridges these freedoms. The freedom of the press is deeply rooted in the country's commitment to democracy and plays a critical role in holding the government accountable to its people.

The interpretation of the First Amendment and its application to the press has been the subject of much debate and litigation. The Supreme Court has clarified that the First Amendment protects the right to publish without prior restraint, marking the beginning of the prior restraint doctrine. This means that the government cannot censor publications before they are released to the public. The Court has also recognised that the press is protected to promote and protect the exercise of free speech in society, including the public's interest in receiving information.

The ACLU and other organisations have played a central role in defending freedom of the press, advocating for a free media that can act as a watchdog over the government. In the Pentagon Papers case, the Supreme Court upheld the publication's right to print, despite national security concerns raised by the Nixon administration. This was a significant victory for press freedom and a recognition of the media's role in keeping the government accountable.

However, the extent to which the press is protected over other speakers has been questioned. In campaign finance law cases, the Supreme Court has rejected the idea that institutional media should receive greater constitutional protection than non-institutional-press businesses. Similarly, in Associated Press v. United States, the Court held that the First Amendment did not exempt newspapers from the Sherman Antitrust Act, demonstrating that press freedom does not sanction repression by private interests.

While the First Amendment provides a strong foundation for press freedom in the U.S., the country's ranking on press freedom indices has varied over the years, with some critics arguing that authorities place undue limits on investigative reporting. Nonetheless, the First Amendment remains a crucial safeguard for democratic ideals and a limitation on government power.

Democrats' Constitution Reading: Limited or Strong?

You may want to see also

The First Amendment and the freedom of speech

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on December 15, 1791, is commonly recognized for its protection of freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and the press, as well as the right to petition the government. The text of the amendment states:

> "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

The First Amendment has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to mean that no branch or section of the federal, state, or local governments can infringe upon American citizens' right to freedom of speech. This interpretation has evolved over time to include protection for more recent forms of communication, such as radio, film, television, video games, and the internet. However, certain forms of expression are not protected by the First Amendment, including commercial advertising, defamation, obscenity, and interpersonal threats.

The freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment includes both direct speech (words) and symbolic speech (actions). Over the years, the Supreme Court has ruled on several cases that clarified the boundaries of protected speech. For example, in West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Court upheld the right of students not to salute the flag. In Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), the Court protected the right of students to wear black armbands to school to protest a war. In Cohen v. California (1972), the Court ruled that offensive words and phrases used to convey political messages were protected.

The First Amendment also protects the freedom of the press, which plays a critical role in American society by disseminating news and information. While the amendment does not grant the media special access to government information, it does protect the press from laws that target or treat different media outlets differently. The amendment has been interpreted to protect the press in order to promote and protect free speech in society, including the public's interest in receiving information.

In conclusion, the First Amendment's protection of freedom of speech and the press are fundamental to American society, fostering individual self-expression, public discussion, and the dissemination of information and ideas. The amendment has been interpreted broadly by the Supreme Court to include various forms of expression and has been a pivotal tenet of American democracy, with roots in the religious and social diversity of colonial America.

Key Constitution Points: A Quick Overview

You may want to see also

The Supreme Court's interpretation of a free press

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

The Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment's protection of freedom of the press in various ways over the years. In some cases, the Court has ruled that laws targeting the press or treating different media outlets differently may violate the First Amendment. For example, in Grosjean v. Am. Press Co. (1936), the Court held that a tax focused exclusively on newspapers violated the freedom of the press. Similarly, in Miami Herald Publ'g Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the Court found that a contempt citation issued to the editor of the Miami Herald violated the First Amendment.

In other cases, the Court has recognised that the press plays a critical role in disseminating news and information, and is therefore entitled to heightened constitutional protections. This includes a degree of governmental sensitivity towards the press. In Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia (1980), several concurring opinions implied recognition of the press's right to gather information, which could not be completely inhibited by nondiscriminatory constraints.

However, the Court has also suggested that the primary purpose of protecting freedom of the press is to promote and protect the exercise of free speech in society at large, including the public's interest in receiving information. For instance, in Consolidated Edison Co. v. PSC (1980), the Court held that commercial speech by a corporation is subject to the same standards of protection as when natural persons engage in it.

The Supreme Court has also interpreted the First Amendment's protection of freedom of the press in relation to specific cases. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court extended protection to good-faith defamation. In Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001), the Court found that the First Amendment protected speech disclosing the contents of an illegally intercepted communication. In Florida Star v. B.J.F. (1989), the Court ruled that the First Amendment prevented a newspaper from being held liable for publishing a rape victim's name.

Despite these interpretations, the Supreme Court has generally extended few substantive rights protections under the Press Clause alone. The Court has also declined to create a constitutionally-based evidentiary privilege for journalists' confidential sources, reasoning that the press has "flourished" without such a privilege for over 200 years.

Bribery Scandals: Violating the US Constitution?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The press as a government watchdog

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees freedom of the press, alongside freedom of speech and religion. This amendment was adopted in 1791 and is deeply rooted in the country's commitment to democracy. The free press clause in the First Amendment has been interpreted and debated extensively, with some arguing that the "'institutional press' should be granted greater freedom from government regulation than non-press entities.

The press plays a crucial role as a government watchdog, holding public officials accountable for their actions. This role was highlighted in the landmark case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), where the Supreme Court ruled that the press could publish false or libelous statements about public officials without fear of retribution. The Court recognised that open discourse about the government and public affairs is vital to a healthy democracy. Justice Brennan emphasised this point, stating that "debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open."

In another significant case, United States v. Manning (2013), Chelsea Manning was found guilty of espionage for providing classified information to WikiLeaks. This case sparked debates about the boundaries of press freedom and the role of whistleblowers in exposing government misconduct.

While the First Amendment protects freedom of the press, it does not grant the media unlimited power. For instance, in Associated Press v. United States (1945), the court held that the Associated Press had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by restricting the sale of news to non-member organisations. This case demonstrated that press freedom does not sanction repression by private interests.

The ranking of the United States in terms of press freedom has fluctuated over the years, with the country placing 42nd in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index in 2022. While the constitutional protections for journalists are commendable, there have been concerns about undue limits on investigative reporting, particularly in the name of national security.

In conclusion, the press serves as a vital watchdog of government activities, ensuring transparency and accountability in a democratic society. The First Amendment's protection of free speech and press rights enables the media to fulfil this role effectively, fostering a vibrant marketplace of ideas and keeping government officials in check.

Interrogation Legality: Determining Constitutional Rights

You may want to see also

The press' right to gather information

The right to freedom of the press in the United States is protected by the First Amendment, which states that "Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press". This right is deeply rooted in the country's commitment to democracy and plays a critical role in holding the government accountable to its people.

The interpretation of the First Amendment and its application to the press has been the subject of much debate and litigation over the years. While the First Amendment guarantees freedom to publish, it does not grant the media special access to information not available to the public. For example, in the case of First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, the Court concluded that the First Amendment did not grant the media the privilege of special access to prisons.

The Supreme Court has also ruled that generally applicable laws do not violate the First Amendment simply because they may have incidental effects on the press. However, the Court has recognised that laws specifically targeting the press or treating different media outlets differently may violate the First Amendment. This was affirmed in Grosjean v. Am. Press Co., where the Court held that a tax exclusively on newspapers violated freedom of the press.

The right to freedom of the press also extends to the publication of false or libelous statements about public officials, as ruled in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. The Court determined that open discourse about the government and public affairs is critical to First Amendment protections, and that spirited criticism and even errors are part of the price of freedom in a democracy.

In conclusion, the press in the United States has a constitutionally protected right to gather information, which is essential for promoting free speech and keeping the government accountable to its citizens. However, this right is not absolute and may be subject to reasonable restrictions, such as national security concerns or statutory provisions preventing the repression of freedom of the press by private interests.

Capital Punishment for Treason: What Does the Constitution Say?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, established in 1791, protects the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press.

Freedom of the press means the absence of prior restraints on publications. It also means that the press is protected in order to promote and protect the exercise of free speech in society at large, including people's interest in receiving information.

No, the First Amendment does not grant the media any special privileges. The Supreme Court has refused to grant increased First Amendment protection to institutional media over other speakers.

![First Amendment: [Connected eBook] (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61-dx1w7X0L._AC_UY218_.jpg)