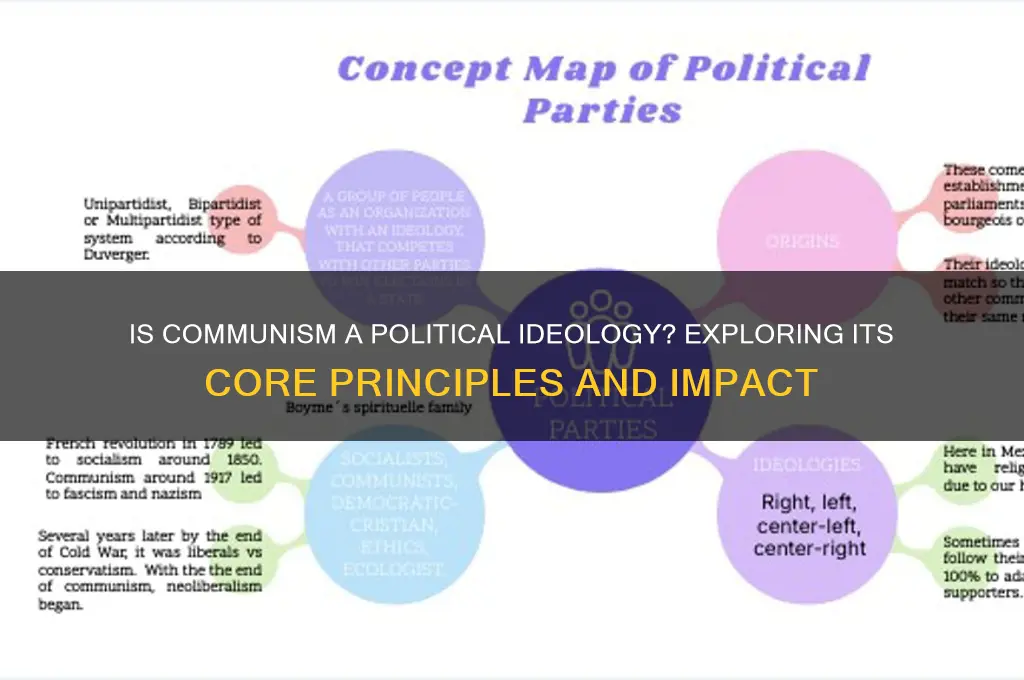

Communism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for a classless, stateless society in which private ownership of property is abolished, and resources are shared equally among all members. Rooted in the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, particularly in *The Communist Manifesto*, it emerged as a critique of capitalism and its inherent inequalities. At its core, communism seeks to establish a system where the means of production are collectively owned, and wealth is distributed according to the principle from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs. While often associated with authoritarian regimes in the 20th century, such as the Soviet Union and China, communism remains a diverse and debated ideology, with proponents arguing for its potential to create a more equitable society and critics highlighting its historical failures and challenges in implementation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Economic System | Abolition of private ownership; collective ownership of means of production |

| Class Structure | Classless society; elimination of social hierarchies |

| Distribution of Wealth | From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs |

| State Role | Transitional dictatorship of the proletariat; eventual withering away |

| Political Philosophy | Marxist theory; emphasis on materialism and historical determinism |

| Equality | Economic and social equality; elimination of exploitation |

| Internationalism | Solidarity among workers globally; opposition to nationalism |

| Labor and Work | Emphasis on collective labor; elimination of wage labor |

| Central Planning | State-controlled economy; planned distribution of resources |

| Revolutionary Approach | Advocacy for proletarian revolution to overthrow capitalism |

| Abolition of Markets | Elimination of market-driven economies; focus on communal production |

| Social Services | Universal access to healthcare, education, and basic needs |

| Ideological Foundation | Rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles; critique of capitalism |

| Cultural Impact | Promotion of collective values; suppression of individualism |

| Historical Examples | Soviet Union, Maoist China, Cuba (with variations in implementation) |

| Criticisms | Authoritarianism, economic inefficiency, suppression of dissent |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of communism

Communism, as a political ideology, traces its roots to the early 19th century, emerging as a response to the social and economic upheavals of the Industrial Revolution. The rapid industrialization of Europe led to stark inequalities, with the working class, or proletariat, enduring harsh conditions while the bourgeoisie amassed wealth. This disparity became the fertile ground for Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who in 1848 published *The Communist Manifesto*, a seminal text that articulated the principles of communism. Their analysis of class struggle and their vision of a stateless, classless society marked the ideological birth of communism, setting it apart from other socialist movements of the time.

To understand communism’s historical origins, one must examine the intellectual and philosophical currents that influenced Marx and Engels. Their ideas were shaped by Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau, who critiqued private property as a source of inequality, and by economists like Adam Smith, whose theories on labor value were reinterpreted in a revolutionary framework. Additionally, the failures of utopian socialism, which sought to create small-scale cooperative communities, pushed Marx and Engels toward a more systemic critique of capitalism. Their approach was not merely theoretical but deeply practical, advocating for a global proletarian revolution to overthrow the bourgeoisie and establish communal ownership of the means of production.

The first practical application of communist principles occurred in the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief but significant uprising where workers seized control of the city. Though short-lived, the Commune provided a real-world example of worker self-governance, inspiring Marx to refine his theories. This event demonstrated the potential for revolutionary change but also highlighted the challenges of sustaining a communist system in the face of opposition from established powers. The Commune’s legacy underscored the importance of organized mass movements and the need for a clear strategy to transition from capitalism to communism.

While communism’s origins are rooted in European intellectual history, its influence quickly spread globally, adapting to diverse cultural and economic contexts. In Russia, Vladimir Lenin’s interpretation of Marxism, known as Leninism, led to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, establishing the world’s first communist state. This marked a significant shift from Marx’s expectation of revolution in industrialized nations, demonstrating communism’s adaptability to agrarian societies. Lenin’s emphasis on a vanguard party and centralized control became a model for subsequent communist movements, though it also introduced tensions between theory and practice, particularly regarding individual freedoms and economic efficiency.

In conclusion, the historical origins of communism are deeply intertwined with the social and economic transformations of the 19th century, shaped by intellectual critiques of capitalism and early revolutionary experiments. From Marx and Engels’ theoretical foundations to the practical lessons of the Paris Commune and the global spread of Leninism, communism evolved as both an ideology and a political movement. Its origins highlight the enduring tension between idealistic visions of equality and the practical challenges of implementation, making it a complex and contested political ideology.

Is Colombia Politically Stable? Analyzing Its Current Political Landscape

You may want to see also

Core principles and key theorists

Communism, as a political ideology, is rooted in the principle of a classless, stateless society where resources are owned collectively and distributed according to need. This vision, though aspirational, demands a critical examination of its core principles and the theorists who shaped them. At its heart lies the abolition of private property, a radical departure from capitalist systems, which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued was the source of exploitation and inequality. Their seminal work, *The Communist Manifesto* (1848), outlines a historical materialist perspective, positing that societal progress is driven by class struggle and economic determinism. This framework remains central to understanding communism’s theoretical foundation.

Marx’s theory of surplus value is a cornerstone of communist ideology, exposing how capitalism extracts profit from workers’ labor. By advocating for collective ownership of the means of production, communism seeks to eliminate this exploitation. However, the transition to such a system requires a dictatorship of the proletariat—a concept Marx introduced as a necessary intermediary phase. This idea has been both a rallying cry and a point of contention, as seen in Vladimir Lenin’s adaptation during the Russian Revolution. Lenin’s *State and Revolution* (1917) expanded on Marx’s framework, emphasizing the role of a vanguard party to lead the working class in overthrowing the bourgeoisie. His practical application of communist theory laid the groundwork for 20th-century socialist states, though critics argue it deviated from Marx’s vision of a stateless end goal.

While Marx and Lenin are foundational, Mao Zedong introduced unique adaptations to communist theory, tailored to China’s agrarian context. Maoism emphasizes the peasantry as a revolutionary force, challenging Marx’s focus on the urban proletariat. His concept of continuous revolution, as outlined in *On New Democracy* (1940), suggests that class struggle persists even after the establishment of a socialist state. This approach influenced movements in the Global South, demonstrating communism’s adaptability to diverse socio-economic conditions. However, Mao’s policies, such as the Great Leap Forward, highlight the risks of ideological rigidity and the human cost of rapid collectivization.

A comparative analysis of these theorists reveals both unity and divergence in communist thought. Marx’s emphasis on economic determinism contrasts with Lenin’s focus on political organization, while Mao’s agrarian-centric approach challenges traditional Marxist orthodoxy. Despite these differences, all three share a commitment to dismantling capitalist structures and achieving egalitarian societies. Yet, the practical implementation of their ideas often led to authoritarianism, raising questions about the feasibility of communism’s core principles in real-world contexts. This tension between theory and practice remains a defining feature of communist ideology.

To engage with communism critically, one must consider its core principles not as immutable dogma but as a framework for addressing systemic inequalities. For instance, Marx’s critique of wage labor remains relevant in discussions of modern labor exploitation, while Lenin’s emphasis on organized action informs contemporary social movements. However, the historical failures of communist regimes underscore the need for nuanced application. Aspiring theorists and practitioners should study these principles not as a blueprint but as a starting point for reimagining equitable systems, mindful of the complexities inherent in any large-scale societal transformation.

Is Black Lives Matter Political? Exploring the Movement's Impact and Intent

You may want to see also

Communism vs. capitalism comparison

Communism and capitalism stand as polar opposites in the spectrum of economic and political ideologies, each with distinct principles, goals, and methods. At their core, communism advocates for a classless, stateless society where resources are owned collectively and distributed according to need, while capitalism champions private ownership, market competition, and profit-driven enterprise. This fundamental divergence shapes their approaches to wealth, power, and social organization, making their comparison both instructive and contentious.

Consider the practical implications of these systems in resource allocation. Under capitalism, supply and demand dictate production and distribution, often leading to innovation and efficiency but also to inequality. For instance, a capitalist healthcare system might produce cutting-edge treatments but leave them inaccessible to those who cannot afford them. In contrast, communism aims to eliminate such disparities by prioritizing communal needs over individual gain. However, historical examples like the Soviet Union and Maoist China reveal challenges in implementation, including inefficiencies and shortages due to centralized planning. This comparison highlights capitalism’s strength in incentivizing progress and communism’s idealistic focus on equity, though both systems face critiques in practice.

To illustrate further, examine the role of the individual within these frameworks. Capitalism thrives on personal ambition and entrepreneurship, rewarding those who succeed in the marketplace. This fosters a dynamic economy but can exacerbate social stratification. Communism, on the other hand, seeks to diminish individualism in favor of collective welfare, often at the cost of personal freedoms and incentives. For example, a capitalist entrepreneur might build a tech empire, while a communist worker contributes to a state-run factory with little personal gain beyond basic needs. This trade-off between individual opportunity and communal equality underscores a key ideological clash.

A persuasive argument for capitalism lies in its adaptability and proven economic growth, as seen in nations like the United States and Germany. Yet, its tendency to concentrate wealth in the hands of a few has sparked global movements advocating for reform. Communism, while appealing in theory, has historically struggled with corruption, lack of incentives, and human rights violations. However, its emphasis on social justice continues to inspire modern movements like universal healthcare and wealth redistribution policies. Both ideologies offer lessons: capitalism on the power of innovation, and communism on the importance of equity.

In conclusion, the communism vs. capitalism debate is not merely academic but deeply practical, influencing policies, economies, and lives worldwide. While capitalism excels in fostering innovation and growth, it often leaves behind the most vulnerable. Communism, though idealistic in its pursuit of equality, has faced significant practical challenges. The ideal system may not be a pure form of either but a hybrid that balances individual opportunity with collective welfare. Understanding their strengths and weaknesses allows for informed decisions in shaping a more equitable and prosperous future.

Brad Pitt's Political Stance: Activism, Influence, and Hollywood's Role

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global communist movements and regimes

Communism, as a political ideology, has shaped global movements and regimes in profound and often contradictory ways. Emerging in the 19th century as a response to industrialization and capitalism, it promised a classless society where resources were shared equitably. Its core tenets—common ownership of the means of production, abolition of private property, and collective governance—have inspired revolutions, governments, and social experiments worldwide. From the Soviet Union to China, Cuba to Vietnam, communist regimes have left indelible marks on history, though their implementations have varied widely in practice.

Consider the Soviet Union, the world’s first communist state, established in 1922. Under Lenin and later Stalin, it pursued rapid industrialization and collectivization, achieving economic growth at the cost of millions of lives during forced famines and political purges. Its influence spread across Eastern Europe post-World War II, creating a bloc of satellite states that adhered to Marxist-Leninist principles. However, the rigidity of its centralized planning and suppression of dissent ultimately contributed to its collapse in 1991. This example underscores the tension between communism’s idealistic goals and the authoritarian methods often employed to achieve them.

In contrast, China’s communist regime, founded in 1949 under Mao Zedong, has evolved significantly. Mao’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution led to catastrophic human and economic losses, yet China’s post-1978 reforms under Deng Xiaoping introduced market elements while retaining single-party rule. Today, China is a global economic powerhouse, blending state control with capitalist practices. This hybrid model challenges traditional definitions of communism, illustrating how the ideology adapts to pragmatic realities.

Cuba offers another unique case. Since its 1959 revolution led by Fidel Castro, it has maintained a communist system despite economic embargoes and the collapse of its Soviet ally. While criticized for political repression, Cuba has achieved notable successes in healthcare and education, providing universal access to both. Its resilience highlights the appeal of communism’s egalitarian ideals, even in the face of external pressures and internal inefficiencies.

Globally, communist movements have also manifested in non-state forms, such as labor unions, cooperatives, and grassroots organizations. These groups advocate for worker rights, wealth redistribution, and democratic control of resources without necessarily seeking state power. Examples include the Zapatista movement in Mexico and Rojava’s autonomous administration in Syria, which experiment with decentralized, communitarian models. These cases demonstrate communism’s adaptability and its potential to inspire alternative social structures beyond traditional regimes.

In analyzing global communist movements and regimes, a key takeaway emerges: communism’s strength lies in its critique of inequality and its vision of collective empowerment, but its weakness often stems from authoritarian implementations and economic inefficiencies. As a political ideology, it continues to evolve, offering both cautionary tales and innovative solutions in the pursuit of a more just society.

End Political Solicitations: Effective Strategies to Reclaim Your Privacy and Peace

You may want to see also

Criticisms and failures of communism

Communism, as a political ideology, has faced significant criticisms and experienced notable failures throughout its implementation in various societies. One of the most glaring issues is the centralization of power, which often leads to authoritarian regimes. In communist states like the Soviet Union and Maoist China, the concentration of authority in the hands of a single party or leader resulted in the suppression of individual freedoms, dissent, and political opposition. This centralization, while intended to ensure equality, paradoxically created systems rife with corruption, inefficiency, and human rights abuses. The absence of checks and balances allowed leaders to prioritize ideological purity over practical governance, often with devastating consequences for their populations.

Another critical failure lies in the economic inefficiencies inherent in communist systems. The abolition of private property and the imposition of state control over production and distribution led to chronic shortages, stagnant growth, and poor living standards. For instance, the Soviet Union’s planned economy struggled to meet basic consumer needs, with long queues for essentials like bread and toilet paper becoming emblematic of its failures. Similarly, in Cuba, the state’s inability to modernize its economy has left the country dependent on foreign aid and remittances. These inefficiencies stem from the lack of market incentives, bureaucratic red tape, and the misallocation of resources, which communist economies have consistently failed to address.

The social and cultural repression under communist regimes is another point of contention. Ideological conformity is enforced through censorship, propaganda, and the suppression of religious and cultural practices. In Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, this extreme repression culminated in the genocide of nearly 2 million people, as the regime sought to create an agrarian utopia by eliminating intellectuals, minorities, and anyone deemed counter-revolutionary. Even in less extreme cases, such as East Germany, the state’s intrusive surveillance apparatus, embodied by the Stasi, fostered a climate of fear and distrust, eroding social cohesion and individual autonomy.

Finally, the global impact of communism’s failures cannot be overlooked. The Cold War, fueled by ideological rivalry between communist and capitalist blocs, led to proxy wars, arms races, and economic instability worldwide. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of communism as a dominant global force but left behind fractured societies, economic disparities, and political instability in many former communist states. Countries like Russia and Eastern European nations continue to grapple with the legacy of authoritarianism, corruption, and weakened institutions. These failures underscore the challenges of implementing an ideology that, while idealistic in theory, has proven unsustainable in practice.

Mastering Assertive Communication: How to Yell Politely and Effectively

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, communism is a political ideology that advocates for a classless, stateless society where resources are owned communally and distributed according to need.

The core principles of communism include common ownership of the means of production, the abolition of private property, egalitarian distribution of resources, and the eventual dissolution of the state.

Communism differs from ideologies like capitalism and socialism by aiming to eliminate class divisions entirely, whereas socialism seeks to reduce inequality within a state structure, and capitalism emphasizes private ownership and market-driven economies.

While communism is not as dominant as it was in the 20th century, it remains relevant as a theoretical framework and is still advocated by some political parties, movements, and thinkers around the world.