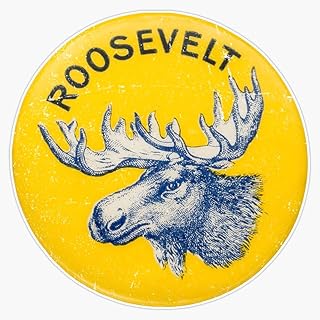

The question of whether the Bull Moose Party, formally known as the Progressive Party, qualifies as a political party in the United States is a topic of historical and political interest. Founded in 1912 by former President Theodore Roosevelt, the Bull Moose Party emerged as a third-party alternative to the Republican and Democratic parties, advocating for progressive reforms such as trust-busting, labor rights, and social welfare. While it achieved notable success in the 1912 presidential election, securing over 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes, its existence was short-lived, dissolving after Roosevelt’s defeat. Despite its brief tenure, the Bull Moose Party is recognized as a significant political movement rather than a long-standing party, as it lacked the enduring structure and sustained influence typically associated with major U.S. political parties. Its legacy, however, continues to shape discussions about third-party politics and progressive ideals in American history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Bull Moose Party (Progressive Party) |

| Founded | 1912 |

| Founder | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Active Years | 1912–1920 (primary period of activity) |

| Political Position | Center to Center-Left |

| Ideology | Progressivism, Trust-Busting, Conservationism, Social Justice |

| Key Policies | New Nationalism, Women's Suffrage, Workers' Rights, Regulation of Corporations |

| Election Performance | 1912 Presidential Election: Theodore Roosevelt (27.4% of popular vote, 88 electoral votes) |

| Current Status | Defunct (merged back into the Republican Party after 1916) |

| Legacy | Influenced modern progressive policies and the Republican Party's platform |

| Symbol | Bull Moose (inspired by Roosevelt's robust campaign style) |

| Notable Figures | Theodore Roosevelt, Hiram Johnson, Gifford Pinchot |

| Party Color | None officially, but associated with Roosevelt's "Bull Moose" imagery |

| Country | United States |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Bull Moose Party origins

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, emerged in 1912 as a bold response to the entrenched corruption and inefficiency of the major political parties in the United States. Its origins trace back to Theodore Roosevelt, the former president, who grew disillusioned with his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party’s drift away from progressive ideals. Roosevelt’s break from the GOP was not merely a personal rift but a principled stand against corporate influence and political stagnation. This schism culminated in his formation of a third party, named after his vigorous campaign style, which he likened to the strength of a bull moose.

To understand the Bull Moose Party’s origins, consider the political climate of the early 20th century. The Progressive Era was marked by calls for social justice, antitrust legislation, and government reform. Roosevelt, a champion of these causes, felt the Republican Party had abandoned them. His “New Nationalism” platform, which advocated for federal regulation of corporations and protection of workers, clashed with Taft’s more conservative approach. When Roosevelt failed to secure the Republican nomination in 1912, he and his supporters bolted, forming the Progressive Party. This move was unprecedented for a former president, signaling the depth of his commitment to reform.

The party’s formation was not just about ideology but also strategy. Roosevelt and his allies recognized the limitations of working within the two-party system, which they viewed as beholden to special interests. By creating a third party, they aimed to disrupt the status quo and force the major parties to address progressive issues. The Bull Moose Party’s platform included groundbreaking proposals such as women’s suffrage, a minimum wage, and social insurance, many of which were later adopted by the Democratic Party. This demonstrates how third parties can drive systemic change, even if they do not win elections.

A key takeaway from the Bull Moose Party’s origins is the power of individual leadership in shaping political movements. Roosevelt’s charisma, combined with his unwavering commitment to reform, galvanized millions of Americans. His famous speech after being shot in Milwaukee—“It takes more than that to kill a bull moose!”—symbolized his resilience and the party’s spirit. While the party disbanded after the 1912 election, its legacy endures in the progressive policies it championed. For those seeking to effect political change today, the Bull Moose Party’s story offers a blueprint: identify a clear vision, mobilize grassroots support, and challenge the establishment when necessary.

Are Political Parties Corporations? Exploring the Legal and Ethical Blurs

You may want to see also

Theodore Roosevelt's role in founding

To understand Roosevelt's impact, consider the party's platform, which was radical for its time. It advocated for women’s suffrage, an eight-hour workday, and social welfare programs—ideas that mainstream parties resisted. Roosevelt’s charisma and popularity as a former president gave the Bull Moose Party immediate credibility, attracting millions of voters in the 1912 election. While he did not win the presidency, his 27% share of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes demonstrated the party’s influence, outperforming Taft’s Republican ticket. This outcome fractured the Republican vote, inadvertently handing the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Roosevelt’s leadership style was instrumental in the party’s formation and appeal. Known for his energetic campaigning and direct communication, he rallied supporters with speeches that emphasized fairness, equality, and the need for government to serve the people, not corporate interests. His ability to connect with diverse groups—from urban workers to rural farmers—was a key factor in the party’s broad appeal. However, the Bull Moose Party’s success was short-lived, dissolving after the 1916 election, largely because it lacked a strong organizational structure independent of Roosevelt’s personality.

A critical takeaway from Roosevelt’s role is his willingness to disrupt the two-party system to advance progressive ideals. While the Bull Moose Party did not endure, its platform influenced future policy, including the New Deal under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt’s bold move underscores the power of individual leadership in shaping political movements, even when they challenge established norms. For those studying political strategy, his example highlights the risks and rewards of breaking away from a major party to pursue principled reform.

Unveiling the Power Players Behind Political News Ownership

You may want to see also

1912 election impact on politics

The 1912 U.S. presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, reshaping the landscape in ways still felt today. At its heart was the Bull Moose Party, formally known as the Progressive Party, led by former President Theodore Roosevelt. This third-party challenge to the Republican Party, then dominated by incumbent President William Howard Taft, fractured the GOP and handed the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. The Bull Moose Party was not just a fleeting protest movement but a significant force that pushed progressive reforms into the national spotlight, even if it failed to win the presidency.

To understand its impact, consider the party’s platform: it advocated for direct primaries, women’s suffrage, workers’ rights, and antitrust legislation—ideas that were radical for the time. These proposals, though not fully realized in 1912, laid the groundwork for future reforms. For instance, the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, was ratified in 1920, and antitrust laws like the Clayton Act were passed in 1914. The Bull Moose Party’s influence extended beyond its immediate electoral failure, demonstrating how third parties can drive policy change even without winning office.

Analytically, the 1912 election exposed the Republican Party’s internal divisions between progressive and conservative factions. Roosevelt’s defection to the Bull Moose Party highlighted the GOP’s inability to reconcile these differences, a problem that persists in modern American politics. The election also underscored the power of personality in politics; Roosevelt’s charisma and popularity kept the Progressive Party competitive, securing it 27% of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes. This remains the strongest third-party performance in U.S. history, a testament to Roosevelt’s appeal and the party’s message.

From a comparative perspective, the 1912 election contrasts sharply with modern third-party efforts, which often struggle to gain traction. Unlike today’s third parties, the Bull Moose Party had a former president as its candidate and a clear, cohesive platform. This historical example suggests that third-party success requires more than just dissatisfaction with the two-party system—it demands strong leadership and a compelling vision. Modern third parties, such as the Libertarian or Green Party, could learn from the Bull Moose Party’s strategic focus on policy and public engagement.

Practically, the 1912 election offers lessons for contemporary politics. It shows that while third parties may not win the presidency, they can force major parties to adopt their ideas. For instance, Roosevelt’s progressive agenda pushed both Democrats and Republicans to embrace reforms in subsequent years. Today, issues like healthcare reform, climate policy, and campaign finance could benefit from similar third-party pressure. Activists and voters can draw inspiration from the Bull Moose Party’s example, using third-party platforms to amplify marginalized issues and hold major parties accountable.

In conclusion, the 1912 election’s impact on U.S. politics is profound and enduring. The Bull Moose Party, though short-lived, left an indelible mark by advancing progressive ideals and exposing the limitations of the two-party system. Its legacy reminds us that political change often begins on the margins, and that third parties, even in defeat, can shape the nation’s future.

Are Mayor and City Council Ward Positions Politically Party-Affiliated?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Progressive Era policies and goals

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, was a short-lived yet impactful political movement in the United States, born out of Theodore Roosevelt's disillusionment with the Republican Party in 1912. Its emergence highlights the broader goals and policies of the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), a period marked by efforts to address the social, economic, and political challenges of rapid industrialization and urbanization. To understand the Bull Moose Party’s role, one must first grasp the Progressive Era’s core objectives: combating corruption, promoting social welfare, and fostering democratic reforms.

Consider the Progressive Era’s focus on trust-busting as a prime example. Industrial monopolies, or "trusts," had stifled competition and exploited consumers. Roosevelt, as president, had already targeted these entities under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Bull Moose Party amplified this goal, advocating for stricter regulation of corporations to ensure fair competition and protect workers. This policy wasn’t just about economic fairness; it was a response to the growing power of big business and its influence over politics. For instance, the party’s platform called for the creation of a federal commission to oversee corporations, a radical idea at the time.

Another key Progressive goal was the expansion of democracy through political reforms. The Bull Moose Party championed initiatives like the direct election of senators, women’s suffrage, and the introduction of primary elections to reduce the power of party bosses. These measures aimed to make government more responsive to the people. Take the example of Oregon, which in 1902 became the first state to adopt the initiative and referendum process, allowing citizens to propose and vote on laws directly. The Bull Moose Party sought to nationalize such reforms, viewing them as essential to combating political corruption and elitism.

Social welfare was also a cornerstone of Progressive policies. The era saw the rise of muckraking journalists exposing unsafe working conditions, child labor, and public health hazards. The Bull Moose Party’s platform reflected these concerns, advocating for workplace safety regulations, minimum wage laws, and protections for children. For instance, they supported the creation of a federal agency to inspect factories and enforce labor standards. This focus on social welfare wasn’t just altruistic; it was a pragmatic response to the human costs of industrialization and a means to build a more stable, productive society.

Finally, the Progressive Era’s emphasis on conservation and environmental stewardship was a hallmark of Roosevelt’s legacy and the Bull Moose Party’s platform. Roosevelt, an avid outdoorsman, had set aside millions of acres of public land for future generations. The party continued this mission, advocating for sustainable resource management and the preservation of natural landscapes. This goal wasn’t merely about protecting nature; it was about ensuring that America’s resources would support economic growth and public health for decades to come.

In sum, the Bull Moose Party’s existence underscores the Progressive Era’s ambitious agenda to reform American society. By targeting corporate power, expanding democracy, improving social welfare, and promoting conservation, the party embodied the era’s ideals. While short-lived, its influence on U.S. politics and policy remains evident, reminding us that progressive change often requires bold, visionary leadership.

Who Controls Politico Comments: Unveiling the Moderation Behind the Platform

You may want to see also

Dissolution and legacy in U.S. politics

The Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, was a short-lived yet impactful political entity in U.S. history, formed in 1912 under the leadership of former President Theodore Roosevelt. Its dissolution in 1920 marked the end of a bold experiment in third-party politics, but its legacy continues to shape American political discourse. The party’s platform, which championed progressive reforms such as trust-busting, women’s suffrage, and labor rights, laid the groundwork for future policy changes, even as the party itself faded into obscurity.

Analytically, the dissolution of the Bull Moose Party can be attributed to its inability to sustain momentum beyond Roosevelt’s charismatic leadership and the fragmented nature of third-party politics in the U.S. electoral system. After Roosevelt’s defeat in the 1912 presidential election, the party struggled to maintain relevance, particularly as many of its progressive ideas were co-opted by the major parties. For instance, Woodrow Wilson’s Democratic administration adopted several Progressive Party policies, such as the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act, effectively neutralizing the party’s unique appeal. This absorption of its agenda into mainstream politics left the Bull Moose Party without a distinct identity, hastening its decline.

Instructively, the legacy of the Bull Moose Party offers a blueprint for modern third-party movements seeking to influence U.S. politics. While the party itself dissolved, its ideas persisted, demonstrating that third parties can drive systemic change even if they fail to win elections. For example, the Progressive Party’s advocacy for direct primaries and the recall of elected officials became standard features of American governance. Activists today can learn from this by focusing on policy-driven campaigns rather than solely on electoral victories, ensuring their ideas outlive their organizational structures.

Comparatively, the Bull Moose Party’s dissolution contrasts with the enduring presence of other third parties, such as the Libertarian or Green Party, which have maintained niche followings despite limited electoral success. Unlike these parties, the Bull Moose Party’s rapid dissolution highlights the challenges of sustaining a third party in a two-party dominant system. However, its legacy underscores the importance of timing and leadership in political movements. Roosevelt’s star power temporarily galvanized support, but without institutional backing or a broad-based coalition, the party could not survive his departure from the political stage.

Descriptively, the Bull Moose Party’s legacy is visible in the progressive reforms that define modern American politics. Its influence is evident in the New Deal policies of the 1930s, which expanded upon the party’s original vision of government intervention to protect citizens from corporate exploitation. Today, debates over healthcare, environmental regulation, and economic inequality often echo the party’s early 20th-century concerns. By framing these issues as matters of social justice and economic fairness, the Bull Moose Party’s ideas remain a cornerstone of progressive thought, even if the party itself is a footnote in history textbooks.

Practically, understanding the Bull Moose Party’s dissolution and legacy can inform contemporary efforts to challenge the two-party system. For instance, third-party candidates and movements can focus on state-level reforms, such as ranked-choice voting or campaign finance reform, to create more fertile ground for their ideas. By studying the Bull Moose Party’s successes and failures, modern activists can avoid the pitfalls of over-reliance on a single leader or narrow policy focus, instead building coalitions that endure beyond election cycles. In this way, the Bull Moose Party’s brief existence continues to offer valuable lessons for anyone seeking to reshape U.S. politics.

Bipartisan Political Committees: Do Both Parties Collaborate in Governance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the Bull Moose Party, officially known as the Progressive Party, was a short-lived political party active from 1912 to 1920. It is no longer a recognized political party in the US.

The Bull Moose Party was a progressive political party formed in 1912 by former President Theodore Roosevelt. It was called the Bull Moose Party after Roosevelt’s claim that he felt "as strong as a bull moose" during his campaign.

No, the Bull Moose Party did not win any presidential elections. Theodore Roosevelt ran as its candidate in 1912 but lost to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, though he outperformed the Republican candidate, William Howard Taft.

The Bull Moose Party advocated for progressive reforms, including trust-busting, women’s suffrage, workers’ rights, and government transparency. It aimed to challenge the conservative policies of the Republican Party.

While the Bull Moose Party no longer exists, its progressive ideals have influenced modern American politics, particularly within the Democratic Party and progressive movements advocating for social and economic reforms.