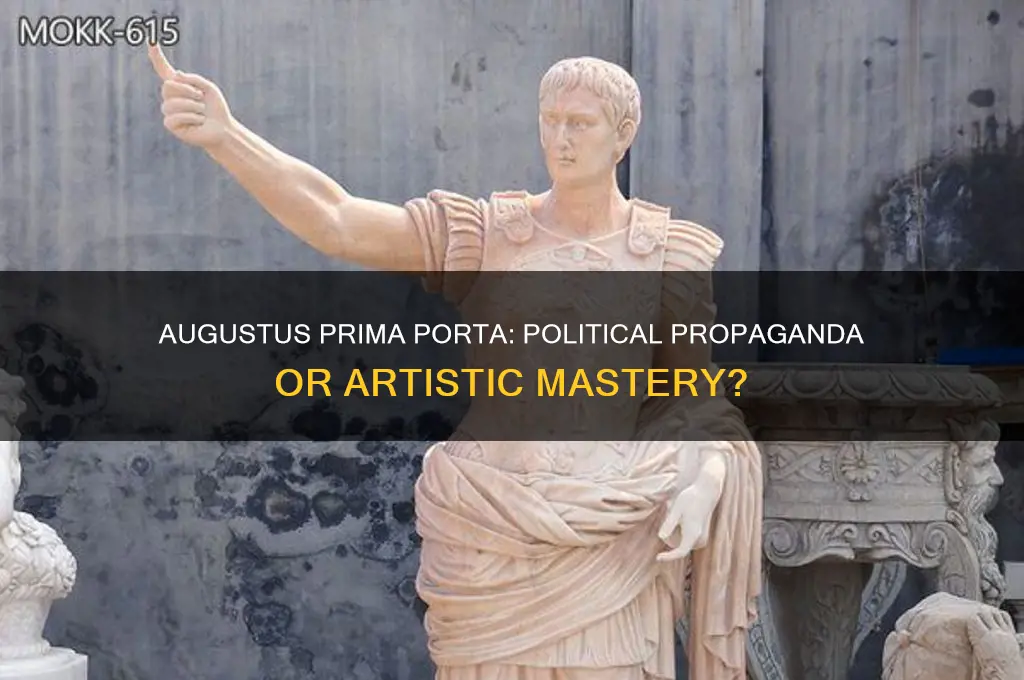

The *Augustus of Prima Porta* is a renowned marble statue of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, dating back to the early 1st century CE. Often analyzed as a masterpiece of Roman art, it is also widely regarded as a powerful piece of political propaganda. The statue meticulously portrays Augustus as an idealized ruler, blending divine, military, and civic authority. Its iconography, including the Cupid at his feet (linking him to the divine Julius Caesar) and the breastplate adorned with symbolic figures like the submission of barbarian tribes, reinforces his legitimacy, power, and role as a bringer of peace and prosperity (*Pax Romana*). Through its strategic placement in Augustus’s villa and its carefully crafted imagery, the statue served to shape public perception, solidify his authority, and promote the ideological values of his reign, making it a quintessential example of ancient political propaganda.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Political propaganda to legitimize Augustus' rule and divine connection. |

| Subject | Augustus, Rome's first emperor, depicted as a youthful, idealized figure. |

| Material | Marble, 2.04 meters tall. |

| Date | Early 1st century AD (circa 20–10 BCE). |

| Location | Originally in Villa of Livia, now in Vatican Museums. |

| Pose | Contrapposto stance, symbolizing balance and authority. |

| Attire | Military armor with a ceremonial cloak, blending civilian and military roles. |

| Accessories | Lorica musculata (muscle cuirass), calceus (military boots), and a sword. |

| Divine Elements | Cupid at his feet, linking him to Venus and divine ancestry. |

| Inscription | Parazonium (dagger) with a scene of the return of Roman standards from Parthia. |

| Iconography | Idealized features, youthful appearance, and symbols of power and peace. |

| Historical Context | Created during Augustus' reign to reinforce the Pax Romana and his authority. |

| Propaganda Elements | Emphasizes Augustus as a just ruler, military leader, and divine descendant. |

| Artistic Style | Classical Greek influence with Roman realism. |

| Symbolism | Armor and weapons symbolize military might; Cupid represents divine right. |

| Audience | Roman elite and public to solidify Augustus' image as a benevolent ruler. |

| Legacy | One of the most iconic representations of Roman imperial propaganda. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Idealized Physical Features

The Augustus of Prima Porta statue, a marble masterpiece from the early Roman Empire, presents an intriguing case study in the idealization of physical features as a tool for political propaganda. This sculpture, believed to be a copy of a now-lost bronze original, depicts Augustus, Rome's first emperor, with a level of physical perfection that transcends mere portraiture. Every detail, from his muscular torso to the intricate drapery of his clothing, serves a strategic purpose, elevating Augustus from a mortal ruler to a divine symbol of Roman power.

Analyzing the Anatomy of Power

The statue's idealized physique is a deliberate construction, drawing upon classical Greek ideals of beauty and proportion. Augustus' body is depicted with a broad chest, defined abdominal muscles, and a subtle yet powerful stance. This physical perfection was not a mere artistic choice but a calculated political statement. In ancient Rome, physical strength and vitality were closely associated with leadership and divine favor. By presenting Augustus with an idealized, almost god-like physique, the sculpture subtly suggests his inherent suitability for rule. This visual language would have been instantly recognizable to Roman citizens, reinforcing the idea of Augustus as a leader blessed by the gods and capable of guiding the empire to prosperity.

A Strategic Drape: The Contrapposto Pose and Beyond

The statue's famous contrapposto pose, with weight shifted onto one leg, adds a sense of relaxed power and naturalism. This pose, borrowed from classical Greek sculpture, further emphasizes Augustus' idealized physique while conveying a sense of approachable authority. The intricate drapery of his clothing, carefully carved to suggest the fall of fabric over his idealized form, adds another layer of symbolism. The intricate folds and subtle creases are not merely decorative; they serve to highlight the underlying muscular structure, reinforcing the image of a ruler who is both physically imposing and refined.

Beyond the Surface: The Power of Idealization

The idealization of Augustus' physical features extends beyond mere aesthetics. It operates on a deeper psychological level, tapping into the Roman concept of "virtus," a combination of physical strength, moral integrity, and courage. By presenting Augustus with a perfect physique, the sculpture subtly suggests that he embodies these virtues, making him the ideal leader for the Roman Empire. This visual propaganda was a powerful tool in an era where literacy was not widespread, and public art played a crucial role in shaping public opinion.

A Lasting Legacy: The Impact of Idealized Imagery

The Augustus of Prima Porta statue stands as a testament to the enduring power of idealized physical features in political propaganda. Its influence can be seen throughout history, from the grandiose portraits of Renaissance rulers to the carefully curated images of modern political leaders. Understanding the strategic use of idealization in this ancient sculpture offers valuable insights into the ways in which visual representation shapes our perceptions of power and leadership, reminding us that the language of the body can be just as powerful as the spoken word.

Unveiling Political Funding: A Step-by-Step Guide to Tracking Donations

You may want to see also

Military Authority Symbolism

The Augustus of Prima Porta statue, a marble masterpiece from the early Roman Empire, is a treasure trove of symbolic elements that reinforce Augustus’ military authority. One of the most striking features is the breastplate adorned with reliefs depicting the return of the Vestal Virgins’ shield, a symbol of Rome’s divine protection, and the Roman gods Mars and Cupid. This imagery strategically links Augustus to both martial prowess and divine favor, positioning him as the protector of Rome’s religious and military traditions. The inclusion of Cupid, riding a dolphin, subtly claims Julian ancestry, tying Augustus to Venus and thus to Rome’s mythical founder, Aeneas. This fusion of military and divine symbolism elevates Augustus beyond a mere mortal leader, embedding his authority in the fabric of Roman identity.

To decode the military authority symbolism further, examine the statue’s posture and accessories. Augustus stands in a contrapposto stance, holding a spear in one hand and extending the other in a gesture of *adlocutio*, the act of addressing troops. This pose is not accidental; it mirrors the authoritative stance of a general commanding his legions. The spear, a symbol of military leadership, reinforces his role as *imperator*, while the outstretched hand evokes the image of a leader who is both approachable and commanding. Practical tip: When analyzing similar artifacts, note the placement of weapons and gestures—they often reveal the subject’s intended relationship to power and authority.

Comparatively, the Augustus of Prima Porta diverges from earlier Republican-era statues, which emphasized civic duty over personal glory. Here, Augustus’ military authority is not just asserted but glorified. The detailed armor, complete with intricate reliefs of battles and victories, serves as a visual résumé of his conquests. Unlike the austere portraits of his predecessors, this statue is a propagandistic tool designed to legitimize his rule in the eyes of the Roman people. For instance, the absence of battle scars or signs of aging contrasts with the realism of earlier works, portraying Augustus as an eternal, unyielding leader. This idealization is a deliberate choice, aimed at fostering loyalty and suppressing dissent.

Finally, consider the statue’s placement within the context of Augustus’ villa at Prima Porta. Its location was no accident; it served as a constant reminder to visitors of Augustus’ role as Rome’s savior and supreme military commander. The symbolism extends beyond the statue itself to its environment, where it would have been surrounded by other artifacts and artworks reinforcing his authority. Takeaway: When evaluating political propaganda in art, always consider the spatial and contextual elements. The setting can amplify the message, turning a static figure into a dynamic symbol of power. For educators or historians, recreating such contexts in exhibits or lessons can deepen understanding of how authority was constructed in ancient societies.

Mastering Polite Communication: Simple Strategies for Gracious Interactions

You may want to see also

Divine Ancestry Depiction

The Augustus of Prima Porta statue, a marble masterpiece from the early Roman Empire, strategically employs divine ancestry depiction to cement Augustus’ political legitimacy. His barefooted stance, a convention reserved for gods in Roman art, immediately signals his semi-divine status. This subtle yet powerful visual cue aligns Augustus with the divine realm, fostering public perception of his rule as sanctioned by the gods.

By draping himself in the iconography of Aeneas, mythical ancestor of the Romans, Augustus forges a direct link to Rome’s foundational myth. The cupid riding a dolphin at his feet, referencing Venus (Aeneas’ mother and Augustus’ claimed ancestor), further reinforces this divine lineage. This clever visual narrative positions Augustus not merely as a ruler, but as the embodiment of Rome’s destiny, his authority intertwined with the city’s divine origins.

This divine ancestry depiction wasn’t merely artistic flourish; it was a calculated political tool. In a society deeply rooted in religious tradition, claiming descent from gods legitimized Augustus’ unprecedented power. It countered potential accusations of tyranny by framing his rule as part of a divine plan, not personal ambition. The statue, likely displayed in his villa, served as a constant reminder to visitors and future generations of his sacred right to rule.

Analyzing the statue’s placement within the broader context of Augustan propaganda reveals a sophisticated strategy. The divine ancestry depiction wasn’t isolated; it worked in tandem with other elements like the military imagery and civic virtues portrayed on the statue. Together, they constructed a multifaceted image of Augustus as a leader blessed by the gods, a skilled general, and a devoted servant of the Roman people.

To fully appreciate the impact of this divine ancestry depiction, consider its audience. The statue wasn’t intended for the uneducated masses but for the Roman elite, well-versed in mythological symbolism. This nuanced messaging, accessible only to the educated, further solidified Augustus’ image as a cultivated and divinely favored leader. Understanding the Augustus of Prima Porta requires recognizing the statue as more than art. It’s a meticulously crafted piece of political propaganda, where divine ancestry depiction plays a pivotal role in shaping public perception and legitimizing Augustus’ reign.

Mastering Comparative Politics: Effective Strategies for Analyzing Global Political Systems

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Contrapposto Pose Analysis

The Augustus of Prima Porta, a marble statue from the early Roman Empire, employs a contrapposto pose that subtly reinforces Augustus’ political authority. This stance, where the weight rests on one leg while the other relaxes, creates a dynamic yet balanced appearance. Originally developed by Greek sculptors to convey naturalism, here it serves a calculated purpose. Augustus’ slight shift in weight, combined with his extended right arm, suggests both accessibility and command. This posture mirrors the classical ideals of moderation (*aurea mediocritas*), positioning Augustus as a leader embodying harmony and stability—key tenets of his reign.

To analyze the contrapposto pose effectively, begin by observing the statue’s hip and shoulder alignment. The hips tilt slightly to the right, while the shoulders remain level, creating a gentle S-curve in the torso. This asymmetry avoids rigidity, projecting an image of relaxed confidence. Compare this to earlier Roman portraits, which often depicted leaders in stiff, frontal poses. Augustus’ stance, by contrast, humanizes him while maintaining an aura of divine calm. Practical tip: When studying similar sculptures, sketch the pose to better visualize the weight distribution and its psychological impact.

A persuasive argument for the contrapposto pose as propaganda lies in its ability to bridge the mortal and divine. Augustus’ left hand, resting casually on a spear, contrasts with the rigid armor and military accoutrements. This juxtaposition of ease and power echoes the Roman concept of *pax Romana*—peace through strength. The pose also aligns with Augustus’ self-presentation as a humble restorer of the Republic, rather than a domineering emperor. By adopting a stance rooted in classical Greek aesthetics, he aligns himself with timeless virtues, subtly elevating his status above mere politics.

Finally, consider the contrapposto pose in its historical context. Augustus commissioned this statue during a period of consolidating power, when visual symbolism was critical to legitimizing his rule. The pose’s naturalism made him relatable to the Roman people, while its classical roots appealed to the elite’s admiration for Greek culture. Caution: Avoid interpreting the pose solely through modern lenses; its effectiveness lies in its resonance with contemporary Roman values. Takeaway: The contrapposto pose is not just an artistic choice but a strategic tool, embedding political messages within the very posture of the emperor.

Is a Black Ribbon Political? Unraveling Its Symbolic Significance and Impact

You may want to see also

Armor and Clothing Meaning

The Augustus of Prima Porta statue, a marble masterpiece from the early Roman Empire, is a visual symphony of political messaging. Its intricate details, particularly the armor and clothing, aren't merely decorative; they're a carefully crafted language of power. Let's dissect this sartorial propaganda.

The Breastplate: A Canvas of Conquest

The intricately carved breastplate, adorned with scenes from the Battle of Actium, isn't just a display of military might. It's a visual shorthand for Augustus' victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, a pivotal moment in his rise to power. The depiction of the god Neptune driving a chariot across the waves subtly links Augustus to divine favor, reinforcing his legitimacy as Rome's leader.

Notice the absence of battle scars or signs of wear. This pristine armor symbolizes not just past victories, but an ongoing state of invincibility and control. It's a message to potential rivals: Augustus is untouchable.

The Lorica Hamata: A Subtle Shift in Power

Beneath the breastplate lies a lorica hamata, a type of mail armor associated with the common soldier. This choice is deliberate. While Augustus was never a military man in the traditional sense, this armor type bridges the gap between the emperor and his troops. It's a calculated move to portray him as a leader who understands the hardships of his soldiers, fostering a sense of camaraderie and loyalty.

The Cloak: Draped in Authority

The meticulously draped cloak, a symbol of Roman citizenship and status, is arranged in a way that suggests both authority and accessibility. The folds are carefully arranged to create a sense of movement, as if Augustus is about to address his people. This dynamic pose, combined with the cloak's symbolic weight, portrays him as a leader who is both commanding and approachable.

Beyond Fabric and Metal: A Language of Legitimacy

The armor and clothing of the Augustus of Prima Porta statue aren't just historical artifacts; they're a sophisticated form of political communication. Every detail, from the triumphant breastplate to the strategically draped cloak, contributes to a carefully constructed image of a ruler who is victorious, connected to his people, and divinely sanctioned. This statue wasn't meant to simply depict Augustus; it was meant to create Augustus, to solidify his image as the embodiment of Roman power and virtue.

Forging Political Alliances: Strategies, Interests, and Historical Dynamics Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the Augustus of Prima Porta is widely regarded as a piece of political propaganda, as it idealizes the Roman Emperor Augustus and emphasizes his divine connections, military prowess, and role as a peaceful ruler.

The statue incorporates symbolic elements like the Cupid at Augustus’s feet (linking him to Venus, the divine ancestor of Rome), the armor with a scene of Roman victory, and the calm, authoritative pose, all of which reinforce his legitimacy and power.

The statue promotes Augustus’s agenda by depicting him as a divine, victorious, and benevolent leader, aligning with his policies of restoring Roman traditions, expanding the empire, and establishing the Pax Romana (Roman Peace).

While it was likely displayed in Augustus’s villa at Prima Porta, its detailed symbolism and idealized portrayal suggest it was also intended to influence perceptions of Augustus among the elite and reinforce his image as the ideal ruler.