The formation of the two dominant political parties in the United States, the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, traces back to the early 19th century, rooted in shifting ideological and regional divides. The Democratic Party emerged from the Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, which emphasized states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government. Following the 1824 presidential election and the demise of the Federalist Party, the Democratic Party solidified its identity under leaders like Andrew Jackson, championing populism and westward expansion. The Republican Party, on the other hand, was established in the 1850s in response to the growing tensions over slavery, uniting former Whigs, Free Soilers, and anti-slavery Democrats. Its formation was driven by a commitment to abolishing slavery, promoting economic modernization, and preserving the Union, culminating in its rise to prominence during the Civil War era. These parties evolved over time, adapting to new issues and demographics, but their origins remain deeply tied to the foundational debates over federal power, slavery, and economic policy that shaped American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Context | The two major political parties in the U.S. (Democratic and Republican) emerged in the early 19th century due to shifting alliances and ideological differences. |

| Founding Period | Democratic Party: Founded in 1828 by Andrew Jackson, evolving from the Democratic-Republican Party. Republican Party: Founded in 1854 by anti-slavery activists in the North. |

| Core Ideologies | Democrats: Initially supported states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government. Republicans: Formed to oppose slavery, emphasizing national unity and economic modernization. |

| Key Issues at Formation | Democrats: Focused on opposing elitism and promoting Jacksonian democracy. Republicans: Centered on abolishing slavery and preserving the Union. |

| Geographical Base | Democrats: Strong in the South and West. Republicans: Dominant in the North and Midwest. |

| Evolution Over Time | Both parties have shifted ideologies: Democrats now emphasize progressive policies, social welfare, and civil rights; Republicans focus on conservatism, limited government, and free-market capitalism. |

| Modern Alignment | Democrats: Associated with liberalism, diversity, and social justice. Republicans: Associated with conservatism, traditional values, and fiscal restraint. |

| Founding Figures | Democrats: Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren. Republicans: Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens. |

| Initial Platform Differences | Democrats: Supported states' rights and agrarian economy. Republicans: Advocated for national banking, tariffs, and anti-slavery policies. |

| Impact of Slavery | The issue of slavery was a major factor in the formation of the Republican Party, leading to the eventual split of the Democratic Party during the Civil War era. |

| Current Party Symbols | Democrats: Donkey. Republicans: Elephant. |

| Latest Data (as of 2023) | Democrats: Focus on healthcare expansion, climate change, and social equity. Republicans: Emphasize tax cuts, border security, and deregulation. |

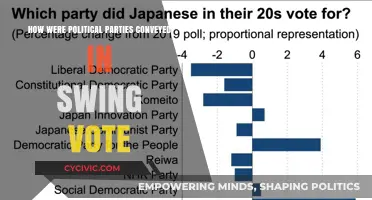

| Voter Demographics | Democrats: Strong support from urban, minority, and younger voters. Republicans: Strong support from rural, white, and older voters. |

| Party Leadership (2023) | Democrats: President Joe Biden. Republicans: House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. |

| Recent Election Performance | Democrats: Won the 2020 presidential election. Republicans: Gained control of the House in 2022 midterms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early Factions in Government

The roots of the two-party system in the United States can be traced back to the early years of the republic, when factions emerged within the government over fundamental questions of governance, economic policy, and the interpretation of the Constitution. These early divisions laid the groundwork for the Democratic and Republican parties that dominate American politics today. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, were the first major factions to crystallize, their disagreements shaping the nation’s political landscape.

Consider the Federalist Party, which emerged in the 1790s as a proponent of a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. Hamilton’s vision of a modernized, industrialized economy clashed with the agrarian ideals of Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, who feared centralized power and favored states’ rights. This ideological split was not merely academic; it influenced critical decisions, such as the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, which the Federalists supported to suppress dissent but which the Democratic-Republicans viewed as an assault on civil liberties. These early debates highlight how factions within government can become the nucleus of enduring political parties.

To understand how these factions evolved into formal parties, examine the role of newspapers and political organizing. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans used publications like *The Gazette of the United States* and *The National Gazette* to spread their messages, effectively creating early forms of party media. Local political clubs and caucuses further solidified these groups, transforming loose coalitions of like-minded politicians into structured organizations. By the 1800 election, these efforts culminated in the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing parties, setting a precedent for partisan competition.

A cautionary note: while early factions were driven by genuine ideological differences, they also exploited regional and economic divisions to consolidate power. The Federalists drew support from New England merchants, while the Democratic-Republicans relied on Southern planters and Western farmers. This regional polarization foreshadowed later conflicts, such as the Civil War. Modern political parties can learn from this history by balancing ideological purity with the need to appeal to diverse constituencies, avoiding the pitfalls of narrow, sectional interests.

In practical terms, the formation of these early factions demonstrates the importance of clear policy platforms and effective communication in building political movements. For instance, Jefferson’s ability to frame the Democratic-Republicans as champions of the “common man” resonated with voters, contributing to their electoral success. Today, parties can emulate this by articulating distinct visions and leveraging media to connect with their base. By studying these early factions, we gain insights into the mechanics of party formation and the enduring challenges of balancing unity and diversity within political organizations.

Are Political Parties Dividing America? A Critical Analysis

You may want to see also

Hamilton vs. Jefferson Ideologies

The rivalry between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson in the late 18th century laid the groundwork for America's first political parties, shaping the nation's ideological divide. Hamilton, as the first Secretary of the Treasury, championed a strong central government and a robust financial system. He believed in a national bank, federal assumption of state debts, and industrialization, arguing these measures would stabilize the economy and foster national unity. Jefferson, in contrast, as the first Secretary of State, advocated for a limited federal government, agrarian economy, and states' rights. This clash of visions—centralization versus decentralization, industry versus agriculture—became the fault line along which the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties emerged.

Consider the practical implications of their ideologies. Hamilton’s financial policies, such as the creation of the First Bank of the United States, aimed to build a creditworthy nation capable of competing globally. For instance, his plan to assume state debts under federal authority not only alleviated state financial burdens but also solidified national cohesion. Jefferson, however, saw such policies as a threat to individual liberty and state sovereignty, warning they would create a financial elite and concentrate power in the hands of the few. This tension highlights how their differing priorities—Hamilton’s focus on economic growth versus Jefferson’s emphasis on preserving republican virtues—directly influenced the formation of opposing political factions.

To understand their impact, examine their stances on foreign policy. Hamilton leaned toward Britain, viewing it as a model for economic development and a crucial trading partner. Jefferson, on the other hand, favored France and its revolutionary ideals, fearing Britain’s monarchical influence would corrupt American democracy. This divide became stark during the French Revolution, where Federalists supported neutrality to protect trade interests, while Jeffersonians backed France, believing in the global spread of republicanism. These contrasting approaches not only deepened the ideological rift but also mobilized supporters into distinct political camps, solidifying party identities.

A comparative analysis reveals how their legacies persist in modern politics. Hamilton’s vision aligns with today’s emphasis on federal intervention in economic matters, such as infrastructure investment and financial regulation. Jefferson’s ideals resonate in contemporary debates over states’ rights and limited government, particularly in rural and agrarian communities. By studying their ideologies, we see how early partisan divisions continue to shape policy debates, from taxation to federal authority. This historical lens offers a practical guide for understanding current political dynamics and the enduring struggle between centralization and local autonomy.

Finally, a persuasive argument can be made that the Hamilton-Jefferson rivalry was not merely a personal feud but a necessary clash of ideas that defined American democracy. Their disagreements forced the young nation to confront fundamental questions about governance, economy, and identity. Without this ideological battle, the two-party system might have lacked the clarity and purpose that have sustained it for centuries. Thus, their conflict serves as a reminder that political polarization, when rooted in principled debate, can be a catalyst for institutional development and democratic resilience.

Georgia's Political Landscape: Understanding the Dominant Party in the State

You may want to see also

Federalist and Anti-Federalist Divide

The Federalist and Anti-Federalist divide emerged during the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, marking the birth of America’s first political factions. At its core, this split reflected differing visions of governance: Federalists championed a strong central government, while Anti-Federalists feared such power would undermine states’ rights and individual liberties. This ideological clash laid the groundwork for the two-party system, shaping political discourse for centuries.

Consider the Federalist perspective as a prescription for national stability. Led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, Federalists argued that a robust federal government was essential to prevent the chaos of the Articles of Confederation era. Their *Federalist Papers*—a series of 85 essays—systematically addressed Anti-Federalist concerns, advocating for checks and balances within a centralized framework. For instance, Federalist No. 10 famously analyzed the dangers of faction and proposed a large republic as the antidote. Practically, this meant supporting the Constitution’s ratification, which required 9 of 13 states to approve—a threshold achieved by 1788.

In contrast, Anti-Federalists, including Patrick Henry and George Mason, viewed the Constitution with skepticism. They warned of tyranny, emphasizing the need for explicit protections of individual rights. Their resistance led to the addition of the Bill of Rights in 1791, a concession that softened opposition but didn’t erase the divide. Anti-Federalists favored a more decentralized system, where states retained significant authority. This stance resonated in rural areas, where distrust of distant elites was palpable. For example, in states like Virginia and New York, Anti-Federalists nearly blocked ratification, demanding amendments to safeguard liberties.

The practical implications of this divide are evident in the formation of early political parties. Federalists, coalescing around Hamilton’s economic policies, became the Federalist Party, while Anti-Federalists evolved into the Democratic-Republican Party under Thomas Jefferson. This split wasn’t merely theoretical; it influenced policy, from Hamilton’s national bank to Jefferson’s agrarian vision. For modern readers, understanding this divide offers a lens into contemporary debates over federal power versus states’ rights, a tension still central to American politics.

To navigate this historical lesson, consider these takeaways: First, political divisions often stem from fundamental disagreements about governance, not just personalities. Second, compromise—like the Bill of Rights—can bridge ideological gaps but rarely resolves them entirely. Finally, the Federalist-Anti-Federalist debate underscores the enduring challenge of balancing centralized authority with local autonomy. By studying this divide, we gain insight into the roots of America’s political system and tools to analyze its evolution.

The Great Political Shift: Did Parties Switch Ideologies Over Time?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of the 1796 Election

The 1796 U.S. presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in the formation of America’s two-party system, crystallizing the ideological divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. This election was the first contested presidential race in U.S. history, marking a shift from the unanimous selection of George Washington to a fiercely competitive battle between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The campaign exposed the deepening rift over the nation’s future: Federalists advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, while Democratic-Republicans championed states’ rights, agrarianism, and alignment with France. This ideological clash transformed personal rivalries into organized political factions, setting the stage for modern party politics.

To understand the election’s role, consider it as a practical experiment in democracy. Unlike Washington’s uncontested terms, 1796 forced voters to choose between competing visions. Federalists, led by Adams, campaigned on stability and economic growth, while Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans warned of Federalist elitism and tyranny. The election machinery itself evolved, with party newspapers, pamphlets, and public rallies becoming tools to mobilize supporters. For instance, Federalist papers like *Gazette of the United States* attacked Jefferson as an atheist, while Democratic-Republican outlets portrayed Adams as a monarchist. This propaganda war laid the groundwork for partisan media, a hallmark of two-party systems.

A critical takeaway from 1796 is the unintended consequence of the electoral process. The Constitution’s original design did not account for political parties, leading to a bizarre outcome: Adams became president, while Jefferson, his ideological opponent, became vice president. This flaw highlighted the need for reform, culminating in the 12th Amendment, which separated presidential and vice-presidential ballots. However, the election’s true legacy was its demonstration of how competing ideologies could coalesce into organized parties. By forcing voters to align with either Federalist or Democratic-Republican principles, 1796 institutionalized the two-party framework that persists today.

Practically, the 1796 election offers a cautionary tale for modern democracies. The polarization it fostered was both a strength and a weakness. While it energized political participation, it also deepened divisions, foreshadowing the partisan gridlock often seen in contemporary politics. For those studying political systems, the election underscores the importance of balancing ideological competition with mechanisms for cooperation. For example, countries with proportional representation systems often avoid extreme polarization by incorporating multiple parties. In contrast, the U.S. system, born in 1796, thrives on binary opposition, a double-edged sword that drives engagement but risks alienating moderate voices.

In conclusion, the 1796 election was not merely a contest between Adams and Jefferson but a crucible for the two-party system. It transformed abstract ideological differences into tangible political organizations, shaping American governance for centuries. By examining this election, we gain insight into the mechanics of party formation and the enduring impact of early political choices. For anyone seeking to understand the roots of modern partisanship, 1796 is a case study in how democracy evolves—and sometimes struggles—under the weight of competing visions.

Political Competition: Healthy Democracy or Divisive Battleground?

You may want to see also

Solidification During the 1800s

The 19th century marked a pivotal era in American politics, transforming loose coalitions into the solidified two-party system we recognize today. The Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties of the early Republic had given way to new alignments by the 1820s, with the Democratic Party and the Whig Party emerging as dominant forces. This period of solidification was characterized by the crystallization of ideological differences, the rise of party machinery, and the expansion of suffrage, which together cemented the two-party structure.

Consider the role of Andrew Jackson’s presidency (1829–1837) as a catalyst for this transformation. Jackson’s Democratic Party championed states’ rights, limited federal government, and the interests of the "common man," appealing to farmers, laborers, and Western settlers. In contrast, the Whig Party, led by figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, advocated for a stronger federal government, internal improvements, and economic modernization, drawing support from urban merchants, industrialists, and Northern voters. This ideological divide created clear distinctions between the parties, making it easier for voters to align themselves with one side or the other.

The expansion of suffrage during this period further fueled party solidification. By the 1830s, most states had eliminated property requirements for voting, dramatically increasing the electorate. Parties responded by building sophisticated organizational structures—local committees, newspapers, and campaign events—to mobilize voters. These efforts turned political participation into a mass phenomenon, with parties becoming vehicles for expressing and shaping public opinion. For instance, the Democratic Party’s use of barbecues, parades, and rallies transformed politics into a communal activity, fostering loyalty and engagement.

However, this solidification was not without tension. The issue of slavery increasingly polarized the parties, particularly after the 1850s. The Whig Party, unable to reconcile its Northern and Southern factions, collapsed, giving way to the emergence of the Republican Party in 1854. The Republicans, with their anti-slavery platform, quickly became the primary opposition to the Democrats, setting the stage for the two-party system that would dominate the post-Civil War era. This realignment underscores how external issues—in this case, slavery—can reshape party identities and structures.

In practical terms, understanding this period offers insights into the mechanics of party formation. Parties thrive when they can clearly articulate distinct ideologies, effectively organize supporters, and adapt to shifting societal demands. The 1800s demonstrate that solidification requires more than just ideological differences; it demands institutionalization through organizational networks and broad-based voter engagement. This historical example serves as a blueprint for how political parties can endure and evolve in a changing democracy.

Exploring the Impact of Political Expression in Modern Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party traces its origins to the Democratic-Republican Party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the 1790s, which opposed the Federalist Party. After the Democratic-Republican Party dominated the 1820s, it split into the modern Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Republican Party was formed in the 1850s by anti-slavery activists, former Whigs, and others who opposed the expansion of slavery, emerging as a major party in the 1860 elections.

Regional and ideological differences were central to the formation of the two parties. The Democratic Party initially represented agrarian interests and states' rights, particularly in the South, while the Republican Party was rooted in the North and focused on industrialization, anti-slavery, and federal authority. These divisions were exacerbated by debates over slavery and economic policies, solidifying the parties' distinct identities.

The two-party system became dominant due to the winner-take-all electoral system, which encourages voters to align with one of the two major parties to maximize their influence. Additionally, the collapse of third parties, such as the Whigs and later the Know-Nothings, left a vacuum that the Democrats and Republicans filled. Over time, these parties adapted to changing issues and demographics, ensuring their continued dominance in American politics.