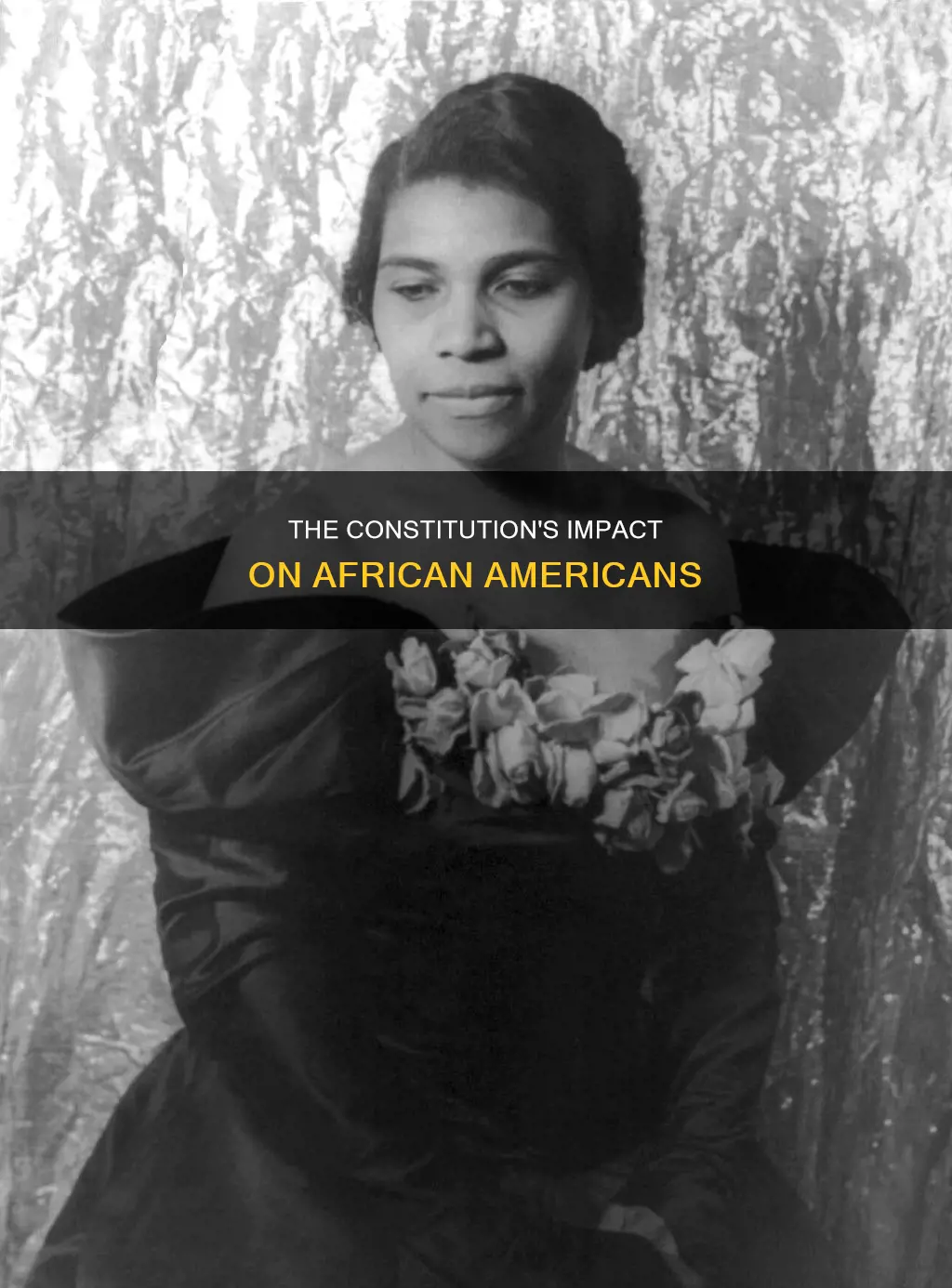

The US Constitution has had a complex and often contradictory impact on African Americans. While the original text did not mention slavery or slaves, the Three-Fifths Compromise increased the power of slave states in Congress. The Dred Scott decision in 1857 denied citizenship to African Americans, and the 14th Amendment only applied to actions taken by the state, not individuals. However, a series of amendments after the Civil War, including the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, granted freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote to African American men. Despite these gains, African Americans continued to face violent opposition, discrimination, and segregation, with their voting rights restricted by poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation. It wasn't until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that further progress was made, with the latter abolishing remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorizing federal supervision of voter registration.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| The 13th Amendment | Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, formally ending the institution of slavery throughout the United States |

| The 14th Amendment | Ratified in 1868, extended liberties and rights granted by the Bill of Rights to formerly enslaved people, and granted citizenship to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States" |

| The 15th Amendment | Passed by Congress and ratified during the Reconstruction Era, granted African American men the right to vote |

| The 1876 Cruikshank ruling | Allowed state legislatures to pass laws restricting citizenship rights, and further highlighted the decision by the Court not to protect the civil rights of African Americans |

| The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision | Legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races, leading to over fifty years of legalized segregation |

| The Civil Rights Act of 1964 | Rooted in the struggle of Americans of African descent to obtain basic rights of citizenship in the nation |

| The Voting Rights Act of 1965 | Abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The 13th Amendment: Outlawing slavery

The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution, passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, abolished slavery in the United States. The Amendment states that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

The 13th Amendment was preceded by President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which declared that "all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free." However, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery nationwide as it only applied to areas of the Confederacy in rebellion against the Union and not to the "loyal" border states that remained in the Union.

Recognizing the limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln advocated for a constitutional amendment to permanently abolish slavery. The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War, before the Southern states had been restored to the Union. While the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. On February 1, 1865, President Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress, submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. By December 6, 1865, the necessary three-fourths of states had ratified the amendment.

The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th Amendments, significantly expanded the civil rights of Americans. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, guaranteed citizenship, and the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, granted African American men the right to vote. These amendments represented significant milestones in the struggle for equality and the expansion of civil rights for African Americans.

The Constitution's Framework for Judicial Power

You may want to see also

The 14th Amendment: Granting citizenship

The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, was a landmark moment in the history of African Americans, as it granted them citizenship and equal protection under the law. The amendment was passed in the wake of the American Civil War, during the Reconstruction Era, a period when the progressive wing of the Republican Party held sway in Congress. This amendment was a direct response to the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford case, in which the Supreme Court declared that Black people, regardless of their free or enslaved status, were not citizens. The 14th Amendment's citizenship clause repudiated this decision, establishing birthright citizenship and ensuring that all persons born or naturalized in the United States were citizens with equal rights.

The amendment's impact was significant, as it provided the legal foundation for African Americans to claim the same constitutional rights as their white counterparts. It empowered them to fight for equal rights, protest against discriminatory laws, and organize conventions across the South to petition Congress. The 14th Amendment also enabled the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which further protected the rights of African Americans.

However, despite the progress, the 14th Amendment's effectiveness in protecting the rights of African Americans faced significant challenges. White southerners violently opposed Black civil rights, and the enforcement of these rights proved difficult. The Supreme Court's narrow interpretation of the amendment in the 1873 Slaughterhouse Cases and the 1876 Cruikshank ruling undermined its impact, allowing states to pass discriminatory laws that restricted African Americans' access to voting and other rights.

The struggle for voting rights was a key aspect of this era. The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, granted African American men the right to vote. However, this progress was short-lived as white supremacists regained control of southern state governments, and voting rights for Black men were rescinded. It wasn't until the 20th century that further progress was made, with the 24th Amendment prohibiting poll taxes in federal elections, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which enforced voting rights for all adult citizens regardless of race or gender.

In conclusion, the 14th Amendment was a pivotal moment in the struggle for African American civil rights, granting them citizenship and providing a legal framework for challenging discrimination. While challenges and setbacks occurred, the amendment laid the groundwork for future progress toward equality, with ongoing activism and legal battles contributing to the expansion of rights for African Americans.

DACA and DAPA: Unconstitutional or Legal?

You may want to see also

The 15th Amendment: Right to vote

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed by Congress on February 26, 1869, and ratified on February 3, 1870, was a significant milestone in the struggle for African American civil rights, granting African American men the right to vote. This amendment, enacted during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, was celebrated by African Americans as the nation's "second birth" and appeared to signify the fulfillment of promises made to them.

The 15th Amendment states that the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the federal government or any state based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." This amendment was a direct response to the long-standing issue of voting rights in the nation, which previously only allowed white men to vote. The amendment was proposed by Republicans, who sought to protect the franchise of black male voters, and it survived a difficult ratification process despite opposition from Democrats.

The impact of the 15th Amendment was evident as African Americans, many of them newly freed slaves, eagerly exercised their right to vote. During Reconstruction, 16 black men served in Congress, and 2,000 black men held elected positions at the local, state, and federal levels. Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce became the first African Americans to serve in the U.S. Senate, representing Mississippi.

However, despite the progress, the 15th Amendment was only a step in the ongoing struggle for equality. African Americans continued to face significant obstacles to voting, including state constitutions and laws, poll taxes, literacy tests, "grandfather clauses," and intimidation by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. The Supreme Court's 1876 Cruikshank ruling further undermined their voting rights, allowing states to pass discriminatory laws. It would take nearly a century of continued efforts and additional legislation, such as the Voting Rights Act of 1965, to address these injustices and secure the voting rights of African Americans.

The 15th Amendment was a crucial step forward, empowering African American men with the right to vote and paving the way for greater political representation. However, the ongoing challenges and the need for further legislative action highlight the enduring struggle for equal rights and the need to safeguard the voting rights of all citizens, regardless of race.

Recognizing Stereoisomers: Constitutional, Diastereomers, and Enantiomers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibited racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson on August 6, 1965, during the height of the civil rights movement. The Act was designed to enforce the voting rights protected by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. It aimed to secure the right to vote for racial minorities, especially in the South, where African Americans faced tremendous obstacles to voting.

Prior to the Act, African Americans in the South were subjected to discriminatory voting practices, including literacy tests, poll taxes, and other bureaucratic restrictions that denied them the right to vote. They also risked harassment, intimidation, economic reprisals, and physical violence when attempting to register or vote. The civil rights movement of the 1960s, led by organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), played a crucial role in pushing for federal action to protect the voting rights of racial minorities.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. It outlawed discriminatory voting practices such as literacy tests and poll taxes, and provided for the appointment of federal examiners to register qualified citizens to vote. The Act also included a provision requiring covered jurisdictions to obtain "preclearance" for any new voting practices and procedures. This ensured that changes could not be made without approval, preventing further discrimination.

The impact of the Voting Rights Act was immediate and significant. By the end of 1965, a quarter of a million new Black voters had been registered, with one-third registered by federal examiners. By the end of 1966, only four out of 13 southern states had fewer than 50% of African Americans registered to vote. The Act was later extended and strengthened in 1970, 1975, and 1982, demonstrating its ongoing importance in protecting the voting rights of African Americans.

However, in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Act involving federal oversight of voting rules in several states. This decision weakened the Act's ability to protect voting rights, and the ongoing struggle for equal voting rights for African Americans continues.

Criminal Justice: Constitutional Limitations and Their Evolution

You may want to see also

Segregation and civil rights

The US Constitution originally did not define voting rights for citizens, and until 1870, only white men were allowed to vote. The Fifteenth Amendment, passed by Congress during the Reconstruction Era and ratified in 1870, granted African American men the right to vote. This amendment was seen as the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans, as it came after the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship. However, the struggle for voting rights continued due to various discriminatory laws and practices that prevented African Americans from fully exercising their right to vote.

The "grandfather clause" was one such method of disenfranchisement, restricting voting rights to men who were previously allowed to vote, effectively excluding African Americans. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation tactics were also used to deny African Americans their right to vote. Despite these challenges, African Americans persisted in their fight for equal rights, with organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and individuals like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and civil rights activists leading the charge.

The US Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson further reinforced segregation, legalizing "separate but equal" facilities for the races. This decision was despite the reality that separate areas provided for African Americans were rarely equal. For more than 50 years, the majority of African American citizens were subjected to second-class citizenship under the "Jim Crow" segregation system.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s brought significant advancements in civil rights for African Americans. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, rooted in the struggle for basic rights of citizenship, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which abolished remaining deterrents to voting, were landmark legislations that secured voting rights for all citizens regardless of race and enforced equal rights under the law. The 1964 Act was prompted by the famous Dred Scott case, which ruled that a person of African descent was not a citizen and had none of the rights guaranteed to US citizens.

Barbados' Constitution River: How Long Does It Flow?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The 13th Amendment, passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, formally ended slavery in the United States. The 14th Amendment, passed on June 13, 1866, and ratified on July 9, 1868, granted citizenship to "all persons born or naturalized in the United States", including formerly enslaved people. The 15th Amendment, passed on February 26, 1870, and ratified on February 3, 1870, granted African American men the right to vote.

Despite the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, African Americans continued to face significant obstacles in exercising their rights. White southerners violently opposed Black civil rights, and state constitutions and laws, poll taxes, literacy tests, the "'grandfather clause'", and intimidation were used to deny African Americans the right to vote. In 1876, the Cruikshank ruling allowed state legislatures to pass laws restricting citizenship rights, and federal troops were withdrawn from the former Confederate states, leading to the dominance of the white supremacist wing of the Democratic Party in the South.

African Americans challenged segregation and demanded their equal rights under the Constitution through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League, as well as through the efforts of individual reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph. The push for voting rights was led by civil rights groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and activists such as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis, and Diane Nash. In 1965, hundreds of protestors marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, to demand voting rights and civil rights for African Americans.