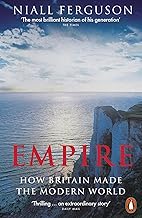

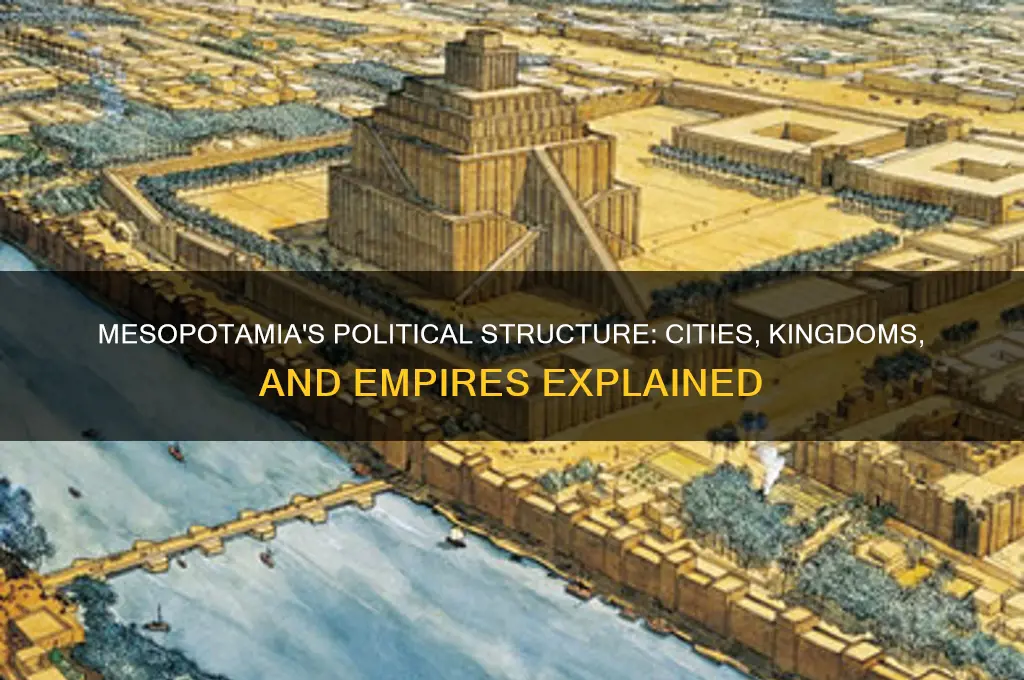

Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, was politically organized through a complex system of city-states, each functioning as an independent political entity with its own ruler, known as a lugal or king. These city-states, such as Uruk, Ur, and Babylon, were often surrounded by fortified walls and governed by a combination of religious and secular authority, with temples playing a central role in administration and resource management. As Mesopotamia evolved, larger empires emerged, such as the Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Empires, which unified multiple city-states under a single ruler through military conquest and centralized governance. Political power was typically legitimized through divine kingship, where rulers claimed to be appointed by the gods, and laws, such as the Code of Hammurabi, were established to maintain order and regulate society. This dynamic political landscape was characterized by frequent conflicts, alliances, and shifts in power, reflecting the region's rich and multifaceted history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Structure | City-states were the primary political units, each with its own ruler, laws, and deities. Examples include Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria. |

| Rulership | Kings held absolute power, often claiming divine authority. They served as military leaders, judges, and religious figures. |

| Centralization | Varying degrees of centralization; some empires (e.g., Akkadian, Neo-Assyrian) unified multiple city-states under a single ruler, while others remained independent. |

| Administration | Bureaucratic systems with officials managing taxation, trade, and public works. Clay tablets with cuneiform script were used for record-keeping. |

| Law Codes | Written legal codes, such as the Code of Hammurabi, established laws and punishments, reflecting social hierarchy and justice. |

| Military Organization | Standing armies were common, with soldiers often conscripted or recruited from the population. Military campaigns were frequent for expansion and defense. |

| Religion and Politics | Religion and politics were intertwined; rulers were seen as intermediaries between gods and people, and temples played a central role in governance. |

| Economic Control | Rulers controlled key economic resources like land, irrigation systems, and trade routes, ensuring wealth and power. |

| Social Hierarchy | Stratified society with kings, priests, nobles, free citizens, and slaves. Social mobility was limited. |

| Diplomacy | Treaties and alliances between city-states and empires were common, often sealed through marriage or tribute agreements. |

Explore related products

$3.99 $11.99

What You'll Learn

- City-States: Independent political units, each with its own ruler and governing system

- Kingship: Divine authority, kings seen as intermediaries between gods and people

- Law Codes: Written laws like Hammurabi’s Code to maintain order and justice

- Administrative Divisions: Regions managed by governors appointed by central authority

- Military Structure: Organized armies led by kings for defense and expansion

City-States: Independent political units, each with its own ruler and governing system

Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, was a region where political organization took a unique and fragmented form. At its core, the political landscape was dominated by city-states—independent entities that functioned as self-governing units, each with its own ruler, laws, and administrative systems. These city-states, such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash, were not merely cities but microcosms of sovereignty, often competing for resources, influence, and dominance. This structure was a direct response to the region's geographical and environmental challenges, where the fertile Tigris and Euphrates rivers enabled localized prosperity but also isolated communities.

Consider the city-state of Uruk, one of the earliest and most influential examples. Its ruler, often a king or ensi, held absolute authority, overseeing religious, military, and economic affairs. The city-state's governance was supported by a bureaucracy of scribes and administrators who managed trade, taxation, and public works. This model was replicated across Mesopotamia, with each city-state adapting its governance to local needs and cultural norms. For instance, while Uruk emphasized military expansion, Lagash focused on irrigation projects and internal stability. This diversity highlights the flexibility and resilience of the city-state system, which allowed for localized innovation while maintaining a broader Mesopotamian identity.

However, the independence of city-states was not without challenges. Constant rivalry and warfare were common, as each sought to expand its territory or secure vital resources. Alliances were fleeting, and power dynamics shifted frequently. To mitigate conflict, city-states occasionally formed temporary coalitions or acknowledged a hegemonic ruler, such as during the Akkadian Empire under Sargon the Great. Yet, these unifications were short-lived, and the region often reverted to its fragmented state. This cyclical pattern underscores the inherent tension between independence and cooperation in Mesopotamia's political organization.

For modern readers seeking to understand this system, a comparative lens can be instructive. Imagine Mesopotamia's city-states as akin to the Italian city-states of the Renaissance, each with its own distinct culture and governance but existing within a shared regional context. Just as Florence and Venice competed and collaborated, so too did Uruk and Ur. This analogy helps illustrate how localized power structures can foster both innovation and conflict, a dynamic that remains relevant in contemporary geopolitics.

In practical terms, the city-state model offers lessons in adaptability and decentralization. For educators or policymakers, studying Mesopotamia's political organization can provide insights into managing diverse communities or designing resilient governance systems. By examining how city-states balanced autonomy with regional interaction, we can glean strategies for addressing modern challenges, from resource allocation to conflict resolution. The legacy of Mesopotamia's city-states lies not just in their historical significance but in their enduring relevance as a blueprint for localized yet interconnected governance.

Crafting Political Poetry: Voice, Vision, and Impactful Verse Creation

You may want to see also

Kingship: Divine authority, kings seen as intermediaries between gods and people

In ancient Mesopotamia, kingship was not merely a political institution but a sacred office, deeply intertwined with religious belief. The king, often referred to as the "shepherd of the people," was seen as the divine intermediary between the gods and humanity. This concept of divine authority was central to the political organization of Mesopotamian city-states, legitimizing the king's rule and shaping the societal hierarchy. The king's role was to maintain the favor of the gods, ensuring prosperity and protection for his people, while also enforcing divine laws and order on Earth.

To understand this system, consider the coronation rituals of Mesopotamian kings. Upon ascending the throne, the king would undergo a sacred marriage ceremony with a high priestess representing the goddess Inanna or Ishtar. This ritual symbolized the king's union with the divine, granting him the authority to govern as the gods' representative. Such ceremonies were not mere formalities but foundational acts that reinforced the king's divine mandate. For instance, the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest legal codes, begins by asserting that the gods Anu and Enlil chose Hammurabi to "prevent the strong from oppressing the weak," explicitly linking his rule to divine will.

This divine kingship had practical implications for governance. The king was responsible for maintaining the temples, ensuring regular sacrifices, and overseeing religious festivals. These duties were not optional but essential to the cosmic order. Failure to fulfill them could result in divine wrath, such as famine, plague, or military defeat. For example, the Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the king's role in appeasing the gods during times of crisis, highlighting the belief that the king's actions directly impacted the well-being of his people. This intertwining of religion and politics meant that rebellion against the king was not just treason but also blasphemy, a challenge to the divine order itself.

However, the king's divine status was not absolute. He was expected to rule justly and wisely, as the gods' representatives on Earth. If a king failed in his duties, the gods could withdraw their favor, leading to his downfall. This belief is evident in Mesopotamian literature, such as the "Curse of Akkad," which describes how the gods abandoned the city due to the king's hubris. Thus, while the king's authority was divine, it was also conditional, dependent on his adherence to the gods' will and his ability to maintain harmony between heaven and Earth.

In conclusion, the concept of kingship in Mesopotamia was a unique blend of political and religious authority, with the king serving as the vital link between the divine and the mortal realms. This system not only legitimized the king's rule but also imposed significant responsibilities, ensuring that governance was aligned with religious principles. By examining the rituals, duties, and consequences of divine kingship, we gain insight into the intricate relationship between power and piety in one of the world's earliest civilizations. Understanding this dynamic offers a lens through which to appreciate the complexity of Mesopotamian society and its enduring influence on the concept of leadership.

Crafting Political Scandals: A Guide to Writing Compelling Controversies

You may want to see also

Law Codes: Written laws like Hammurabi’s Code to maintain order and justice

Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, was a region where the concept of written law took root and flourished. Among the most renowned of these early legal systems is the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian legal code that dates back to around 1754 BCE. This code, inscribed on a towering basalt stele, stands as a testament to the Mesopotamian commitment to maintaining order and justice through formalized, written laws. Its 282 provisions covered a wide range of societal issues, from economic transactions and family law to criminal offenses, demonstrating the complexity and sophistication of Mesopotamian governance.

To understand the significance of law codes like Hammurabi’s, consider their role in standardizing justice across diverse city-states. Before written laws, justice was often arbitrary, varying from one ruler or judge to another. The Code of Hammurabi introduced a uniform set of rules, ensuring that similar offenses received similar punishments regardless of the individual involved. For example, the principle of "an eye for an eye" (lex talionis) was explicitly codified, providing clarity and predictability in legal matters. This standardization not only reduced disputes but also reinforced the authority of the ruler, as the law was seen as an extension of divine will.

Implementing such a legal system required a structured approach. First, the laws had to be widely disseminated. Copies of the Code of Hammurabi were placed in public spaces, such as temples and city centers, to ensure accessibility. Second, a trained class of scribes and judges was essential to interpret and enforce the laws. These officials were often educated in the cuneiform script, the writing system used in Mesopotamia, and were expected to apply the law impartially. Third, the legal system was integrated into the broader political hierarchy, with the king at its apex, acting as the ultimate arbiter of justice.

Despite its advancements, the Mesopotamian legal system was not without limitations. The Code of Hammurabi, for instance, reflected the social hierarchy of its time, with different penalties for the elite and commoners. A free man who caused the death of another free man’s slave, for example, was fined one-third of a mina (a unit of weight used for currency), while more severe punishments were reserved for offenses against higher-status individuals. This disparity highlights the code’s role in maintaining existing power structures rather than promoting equality. Nonetheless, it marked a significant step toward the rule of law, influencing legal traditions for centuries to come.

In practical terms, the legacy of Mesopotamian law codes can be seen in their emphasis on documentation and precedent. Modern legal systems still rely on written laws and case histories to guide decisions, a practice rooted in the ancient practice of inscribing laws on stone or clay tablets. For those studying or practicing law today, examining the Code of Hammurabi offers valuable insights into the origins of legal principles such as proportional punishment and the protection of property rights. By studying these early laws, we gain a deeper appreciation for the enduring quest to balance authority with justice.

Mastering Political Warfare: Effective Strategies to Launch Powerful Attacks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Administrative Divisions: Regions managed by governors appointed by central authority

Mesopotamia's political organization often featured a system of administrative divisions, where regions were managed by governors appointed by a central authority. This structure allowed for efficient governance of vast territories, ensuring that local affairs were handled while maintaining the power and influence of the central ruler. The governors, often referred to as ensis in Sumerian or shakkanakkus in Akkadian, were typically loyal officials or relatives of the king, tasked with overseeing taxation, justice, and military affairs in their respective provinces.

Consider the Neo-Assyrian Empire, a prime example of this system. The empire was divided into provinces, each headed by a governor appointed by the king. These governors were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining order, and providing troops for the king’s military campaigns. To ensure loyalty, the central authority often rotated governors or appointed individuals with no local power base. This practice minimized the risk of rebellion and kept the provinces firmly under imperial control. The system’s effectiveness is evident in the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s ability to manage a diverse and expansive territory for centuries.

However, implementing such a system required careful oversight. Governors wielded significant power, and corruption or mismanagement could undermine the central authority. To mitigate this, Mesopotamian rulers often employed inspectors or royal correspondents to monitor governors’ activities. These officials reported directly to the king, providing a check on local authority. Additionally, written records, such as clay tablets detailing tax collections and legal judgments, were maintained to ensure transparency and accountability.

A comparative analysis reveals that this administrative model was not unique to Mesopotamia. The Persian Empire, for instance, adopted a similar system of satrapies, where satraps (governors) managed regions under the authority of the Great King. However, Mesopotamia’s system predated this by centuries, suggesting it served as a foundational model for later empires. The key difference lies in the degree of centralization; Mesopotamian governors often had less autonomy than their Persian counterparts, reflecting the region’s emphasis on strong royal authority.

For modern readers seeking to understand this system, imagine a corporate structure where regional managers oversee local operations but report to a CEO. The CEO (the king) sets overarching policies, while managers (governors) handle day-to-day affairs. However, unlike in a corporation, Mesopotamian governors operated in a pre-industrial context, relying on manual labor, barter economies, and limited communication networks. This analogy highlights both the similarities and unique challenges of ancient governance.

In conclusion, Mesopotamia’s administrative divisions, managed by governors appointed by a central authority, were a cornerstone of its political organization. This system balanced local administration with royal control, enabling the governance of large and diverse territories. By studying its mechanisms—appointment practices, oversight methods, and historical examples—we gain insights into the complexities of ancient statecraft and its enduring influence on political systems.

Navigating Neutrality: Strategies to Avoid Political Conversations Effectively

You may want to see also

Military Structure: Organized armies led by kings for defense and expansion

The military structure of ancient Mesopotamia was a cornerstone of its political organization, with organized armies led by kings serving as both a defensive shield and an offensive sword. These armies were not merely collections of warriors but highly structured forces designed to protect city-states and expand their influence. The king, often seen as a divine figure, held absolute command, ensuring loyalty and discipline through a combination of religious authority and practical incentives. This centralized leadership allowed for rapid mobilization and coordinated campaigns, which were essential in a region where conflicts over resources and territory were frequent.

Consider the example of Sargon of Akkad, who unified much of Mesopotamia under his rule around 2334 BCE. His military success relied on a standing army composed of professional soldiers, a departure from the earlier reliance on conscripted farmers. Sargon’s forces included specialized units such as archers, spearmen, and charioteers, each trained for specific roles on the battlefield. This level of organization not only enhanced combat effectiveness but also projected power, deterring potential rivals and securing trade routes. By studying Sargon’s model, one can see how military structure was integral to political stability and expansion in Mesopotamia.

To understand the practicalities of Mesopotamian military organization, imagine the following steps: first, recruitment was often based on a combination of conscription and voluntary service, with soldiers drawn from both urban and rural populations. Second, training was rigorous, focusing on discipline, formation tactics, and the use of weapons like the composite bow and bronze-tipped spears. Third, logistics were critical, with armies relying on supply lines to transport food, water, and equipment. Kings like Hammurabi of Babylon further refined this system by integrating military service with civic duties, ensuring a steady supply of trained men. These steps highlight the meticulous planning required to maintain an effective military force.

A comparative analysis reveals that Mesopotamian military structures were ahead of their time, particularly in their use of technology and strategy. While neighboring regions often relied on tribal militias or loosely organized bands, Mesopotamian armies employed advanced weaponry, such as the chariot, which became a symbol of power and prestige. Additionally, the construction of fortified walls and ziggurats served dual purposes: as defensive barriers and as demonstrations of a city-state’s strength. This blend of innovation and pragmatism set Mesopotamia apart, allowing its rulers to dominate the region for centuries.

In conclusion, the military structure of Mesopotamia was a dynamic and essential component of its political organization. Led by kings who wielded both secular and divine authority, these armies were instruments of defense, expansion, and consolidation. Through examples like Sargon’s standing army and the logistical innovations of Hammurabi, we see a system designed to adapt to the challenges of its time. For modern readers, this serves as a reminder of how military organization can shape the destiny of civilizations, offering lessons in leadership, strategy, and resource management that remain relevant today.

Mastering the Art of Gracious Declination: Polite Ways to Say No

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

During its early periods, Mesopotamia was organized into city-states, each ruled by a king or ensi. These city-states, such as Uruk, Ur, and Lagash, were independent political units with their own gods, laws, and territories. They often competed for resources and power, leading to frequent conflicts.

Religion played a central role in Mesopotamian politics. Kings were seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, and their legitimacy to rule was often tied to divine favor. Temples, known as ziggurats, were major political and economic centers, and priests held significant influence in governance.

The Akkadian Empire, founded by Sargon of Akkad around 2334 BCE, was the first empire in Mesopotamia. It unified many city-states under a single ruler, marking a shift from independent city-states to a centralized imperial system. This empire introduced standardized laws and administration, though local city-state identities persisted.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BCE) was highly centralized, with the king holding absolute power. It was divided into provinces governed by appointed officials. The empire was known for its efficient bureaucracy, codified laws (such as the Code of Hammurabi), and grand public works, including the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.