The relationship between education levels and political party support is a fascinating and complex topic that sheds light on the diverse ways voters align themselves with political ideologies. Research consistently shows that education plays a significant role in shaping political preferences, with higher levels of education often correlating with support for more progressive or liberal parties, while lower levels of education may be associated with conservative or populist movements. This phenomenon can be observed across various countries, where educated voters tend to prioritize issues such as social justice, environmental sustainability, and global cooperation, whereas less educated voters might focus on economic stability, traditional values, and national sovereignty. Understanding these patterns is crucial for political parties to tailor their campaigns and policies effectively, ensuring they resonate with different educational demographics and ultimately influencing the outcome of elections.

Explore related products

$0.99 $4.73

What You'll Learn

- Educational Attainment and Party Affiliation: Higher education often correlates with support for progressive or liberal parties

- STEM vs. Humanities Graduates: STEM graduates lean conservative; humanities graduates tend to support liberal policies

- Impact of Vocational Training: Vocationally trained voters often align with parties emphasizing economic pragmatism

- Elite Universities and Political Leanings: Graduates from elite institutions frequently support centrist or globalist parties

- Education Level and Voter Turnout: Higher education levels consistently predict higher political participation and party loyalty

Educational Attainment and Party Affiliation: Higher education often correlates with support for progressive or liberal parties

Higher education levels consistently correlate with increased support for progressive or liberal political parties across many democracies. Data from the United States, for instance, shows that college graduates are significantly more likely to identify with or vote for the Democratic Party, while those with a high school education or less tend to favor the Republican Party. This trend isn’t unique to the U.S.; similar patterns emerge in countries like the United Kingdom, Canada, and Germany, where higher educational attainment often aligns with support for left-leaning parties. This correlation raises questions about the mechanisms driving this relationship: Does education shape political beliefs, or do individuals with certain predispositions pursue higher education?

One explanation lies in the exposure to diverse ideas and critical thinking fostered by higher education. College curricula often emphasize social sciences, humanities, and interdisciplinary studies that challenge traditional norms and encourage empathy for marginalized groups. For example, courses on sociology, gender studies, or environmental science frequently highlight systemic inequalities and the need for progressive policies. This intellectual environment can shift individuals’ perspectives toward more liberal stances on issues like healthcare, immigration, and climate change. Conversely, those with less formal education may rely more on local communities or traditional media, which often reinforce conservative values.

However, the relationship isn’t deterministic. Education level alone doesn’t dictate political affiliation; socioeconomic factors, geographic location, and cultural upbringing also play significant roles. For instance, a working-class individual with a college degree might still align with conservative parties if their economic interests or cultural identity are better represented by those platforms. Similarly, a highly educated individual in a rural area may prioritize local economic concerns over progressive ideals. Thus, while education is a strong predictor, it interacts with other variables to shape political preferences.

To leverage this correlation practically, political campaigns targeting highly educated voters should focus on policy specifics rather than broad ideological appeals. For example, emphasizing data-driven solutions to climate change or detailed plans for education reform can resonate with this demographic. Conversely, campaigns aiming to sway less-educated voters might benefit from framing progressive policies in terms of tangible, immediate benefits, such as job creation or cost savings. Understanding these nuances can help parties tailor their messaging to bridge the educational divide and build broader coalitions.

Ultimately, the link between higher education and support for progressive parties underscores the transformative power of knowledge in shaping political attitudes. While education is not the sole factor, its influence is undeniable, offering both opportunities and challenges for political strategists. By recognizing this dynamic, parties can craft more effective outreach strategies and foster a more informed electorate, regardless of educational background.

Understanding Ranon: Its Role, Impact, and Influence in Modern Politics

You may want to see also

STEM vs. Humanities Graduates: STEM graduates lean conservative; humanities graduates tend to support liberal policies

Educational background significantly shapes political leanings, with STEM graduates often aligning with conservative ideologies and humanities graduates gravitating toward liberal policies. This divide isn’t arbitrary; it reflects differing priorities and worldviews cultivated through distinct academic disciplines. STEM fields, emphasizing objectivity, data-driven solutions, and individual achievement, resonate with conservative values like limited government intervention and free-market principles. Conversely, humanities disciplines, which explore societal structures, historical injustices, and ethical dilemmas, foster a perspective that prioritizes social equity, collective welfare, and progressive change.

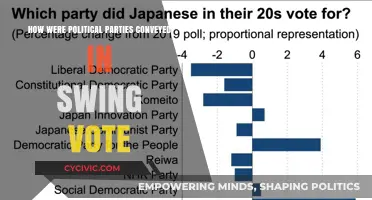

Consider the practical implications of this split. A computer science graduate, trained to solve problems through algorithms and efficiency, might support deregulation to foster innovation, while an English literature major, steeped in critical analysis of power dynamics, could advocate for policies addressing systemic inequality. These aren’t just theoretical differences—they manifest in voting patterns. Studies show that STEM graduates are more likely to vote Republican, while humanities graduates overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates. For instance, a 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that 58% of STEM graduates identified as conservative or moderate, compared to 37% of humanities graduates.

To bridge this gap, educators and policymakers must encourage interdisciplinary dialogue. STEM programs could incorporate ethics courses to broaden perspectives, while humanities curricula could integrate data literacy to ground idealism in practical realities. Employers also play a role by fostering workplace cultures that value diverse viewpoints, ensuring that STEM and humanities graduates collaborate rather than clash. For individuals, seeking out diverse media and engaging in cross-disciplinary discussions can mitigate the echo chamber effect.

Ultimately, understanding this STEM-humanities political divide isn’t about labeling or stereotyping but about recognizing how education shapes our worldview. By acknowledging these differences, we can foster more informed, empathetic, and constructive political discourse. Whether you’re a STEM graduate questioning your conservative leanings or a humanities alum reevaluating your liberal stance, the key is to remain open to new ideas and evidence. After all, the most effective solutions often emerge at the intersection of logic and empathy.

Exploring the Existence of a Moderate Political Party in the US

You may want to see also

Impact of Vocational Training: Vocationally trained voters often align with parties emphasizing economic pragmatism

Vocationally trained voters, equipped with skills directly applicable to the workforce, often gravitate toward political parties that prioritize economic pragmatism. This alignment stems from their firsthand experience with the tangible outcomes of policy decisions on employment, wages, and industry growth. Unlike traditional academic pathways, vocational training fosters a results-oriented mindset, making these voters particularly sensitive to policies that promise job stability, infrastructure investment, and trade agreements benefiting their sectors. For instance, a plumber or electrician is more likely to support a party advocating for apprenticeships and small business tax breaks than one focused on abstract ideological debates.

Consider the case of Germany, where the dual education system integrates vocational training with workplace experience. Here, vocationally trained voters consistently favor parties like the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) or the Social Democratic Party (SPD), which emphasize labor market reforms and industrial competitiveness. In contrast, countries with weaker vocational systems, such as the United States, see these voters split between parties, often swayed by short-term economic promises rather than systemic reforms. This highlights the importance of vocational training not just as a career pathway but as a political socialization tool that shapes policy preferences.

To maximize the political impact of vocational training, policymakers should focus on three key areas. First, align curricula with emerging industries like renewable energy or digital manufacturing to ensure voters perceive parties supporting these sectors as forward-thinking. Second, foster partnerships between training institutions and local businesses to create a feedback loop where economic policies are directly tied to community prosperity. Third, provide data-driven insights into how specific policies—such as tax incentives for hiring apprentices—translate into job creation, reinforcing the pragmatic appeal for vocationally trained voters.

However, caution is warranted. Overemphasis on economic pragmatism can lead vocationally trained voters to overlook broader social issues like healthcare or education, which indirectly affect their livelihoods. Parties courting these voters must balance sector-specific appeals with holistic policy frameworks. For example, a party advocating for infrastructure spending should also address how improved transportation networks reduce commute times for skilled workers, thereby enhancing productivity and work-life balance.

In conclusion, vocationally trained voters are a critical demographic for parties emphasizing economic pragmatism, but their support is not automatic. It requires targeted policies, clear communication of tangible benefits, and a recognition of their unique perspective shaped by hands-on training. By understanding this dynamic, political parties can craft messages that resonate deeply with this group, turning their skills into votes and their votes into sustainable economic policies.

Understanding Political Appointees: Roles, Responsibilities, and Impact on Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Elite Universities and Political Leanings: Graduates from elite institutions frequently support centrist or globalist parties

Graduates from elite universities often exhibit a pronounced tendency to support centrist or globalist political parties, a phenomenon that warrants closer examination. This trend is not merely coincidental but can be traced to the unique educational and social environments these institutions foster. Elite universities, such as Harvard, Oxford, or the London School of Economics, are known for their rigorous academic programs, diverse student bodies, and emphasis on critical thinking. These factors collectively shape graduates’ political inclinations, steering them toward ideologies that prioritize moderation, international cooperation, and evidence-based policymaking.

Consider the curriculum and extracurricular experiences typical of elite institutions. Courses in economics, political science, and international relations often highlight the complexities of global systems, encouraging students to view issues from a transnational perspective. For instance, a study by the Pew Research Center found that individuals with advanced degrees are more likely to support free trade agreements and international alliances, key tenets of globalist agendas. Additionally, exposure to diverse peers from various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds fosters empathy and a broader worldview, further aligning graduates with centrist values that seek compromise over polarization.

However, this alignment is not without its critiques. Some argue that the elitism inherent in these institutions can create a disconnect between graduates and the broader electorate. The perception that elite university alumni form a political class out of touch with grassroots concerns has fueled backlash in recent years. For example, the rise of populist movements in both the U.S. and Europe has often been framed as a reaction against the globalist elites, many of whom are perceived to have graduated from such institutions. This tension underscores the need for graduates to balance their centrist or globalist leanings with an awareness of local and national realities.

Practical steps can be taken to bridge this gap. Graduates from elite universities can engage in community-based initiatives, leveraging their education to address local challenges while maintaining a global perspective. For instance, alumni networks can organize workshops on policy issues, ensuring that their insights are accessible to a wider audience. Similarly, institutions themselves can redesign curricula to include more case studies on regional politics and economies, grounding students in both global and local contexts. By doing so, graduates can embody the centrist ideal of balancing universal principles with specific, actionable solutions.

In conclusion, the political leanings of elite university graduates toward centrist or globalist parties are shaped by their educational experiences but must be tempered by an awareness of broader societal dynamics. While their support for moderation and international cooperation is valuable, it is equally important to remain attuned to the concerns of diverse populations. By actively engaging with local communities and integrating regional perspectives into their worldview, these graduates can contribute meaningfully to political discourse, ensuring that their education serves as a bridge rather than a barrier.

Hollywood's Sex Scandals: Unveiling the Political Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Education Level and Voter Turnout: Higher education levels consistently predict higher political participation and party loyalty

Higher education levels are a reliable predictor of both voter turnout and consistent party loyalty, a trend observed across numerous democracies. Studies show that individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher are 15-20 percentage points more likely to vote in national elections compared to those with only a high school diploma. This gap widens in local elections, where educated voters participate at nearly double the rate of their less-educated counterparts. The correlation isn’t merely about access to information; it reflects a deeper engagement with civic processes fostered through higher education. For instance, college curricula often include courses on political science, history, and sociology, which encourage critical thinking about governance and the role of citizenship.

This relationship isn’t static—it evolves with age and experience. Among voters aged 18-29, those with some college education are 30% more likely to vote than those with only a high school education. However, by age 65, this gap narrows to 10%, suggesting that life experience and socioeconomic stability begin to offset the initial educational advantage. Party loyalty also strengthens with education; college-educated voters are 25% more likely to consistently support the same party across multiple election cycles. This loyalty is often tied to policy alignment, as higher education tends to correlate with a deeper understanding of complex issues like healthcare reform, climate policy, and tax structures.

To harness this trend, political campaigns should tailor strategies to engage both highly educated and less-educated voters. For the former, focus on detailed policy proposals and town hall meetings that encourage dialogue. For the latter, prioritize accessible messaging and community-based outreach programs. Practical tips include partnering with local colleges to host voter registration drives and using social media platforms to disseminate simplified yet accurate policy summaries. Campaigns can also leverage alumni networks to mobilize educated voters, offering them roles as volunteers or spokespersons to amplify their reach.

A cautionary note: while higher education fosters participation, it can also deepen political polarization. Educated voters are more likely to consume partisan media and engage in echo chambers, reinforcing their existing beliefs. Campaigns must balance targeted outreach with efforts to bridge divides, such as hosting bipartisan forums or emphasizing shared values. Ultimately, understanding the link between education and voter behavior isn’t just about predicting turnout—it’s about crafting inclusive strategies that strengthen democratic engagement across all levels of society.

Understanding Political Party Percentages: A Comprehensive Breakdown of Representation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, education level often correlates with political party support. Higher levels of education tend to align with more liberal or progressive parties, while lower levels of education sometimes correlate with conservative or populist parties, though this varies by country and context.

Highly educated voters often support center-left, liberal, or progressive parties that emphasize policies like education funding, social equality, and environmental sustainability. Examples include the Democratic Party in the U.S. or the Social Democratic Party in Germany.

Less educated voters may support conservative or populist parties due to concerns about economic security, cultural preservation, or skepticism of elite institutions. These parties often appeal to traditional values and promise to address perceived neglect by establishment politics.

Education shapes voter priorities by exposing individuals to diverse ideas and fostering critical thinking. Highly educated voters often prioritize issues like healthcare, climate change, and social justice, while less educated voters may focus on economic stability, job security, and cultural identity.