Constitutive equations are mathematical expressions that describe how materials respond to external forces, characterizing the relationships between stress, strain, and time. They are crucial for predicting material behaviour in fields like engineering and physics, especially under various conditions such as temperature changes or deformation. Constitutive equations are derived from fundamental laws such as the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, and they are combined with other equations to solve physical problems. Velocity, on the other hand, is defined as the rate at which displacement changes with time, and its formula is given by velocity (v) = displacement (d) / time (t). This paragraph will explore the relationship between these two concepts and provide insight into how one can solve for velocity given a constitutive equation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Constitutive equations are mathematical expressions that describe how materials respond to external forces, characterizing the relationships between stress, strain, and time. |

| Use | Constitutive equations are crucial for predicting material behaviour in fields like engineering and physics, especially under various conditions such as temperature changes or deformation. |

| Types | Constitutive equations can be empirical (based on measurements) or theoretical (based on statistical mechanics, transport theory, or condensed matter physics). They can also be phenomenological or derived from first principles. |

| Applications | Constitutive equations are used in fluid mechanics, solid-state physics, structural analysis, nuclear thermal-hydraulics, and more. |

| Velocity Calculation | The formula for velocity is given by velocity (v) = displacement (d) / time (t). |

| Velocity Definition | Velocity is defined as "the rate at which displacement changes with time." |

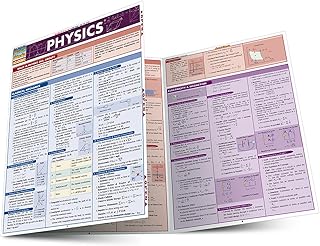

Explore related products

$174.6 $224.95

$43.43 $46.9

What You'll Learn

Velocity in fluid mechanics

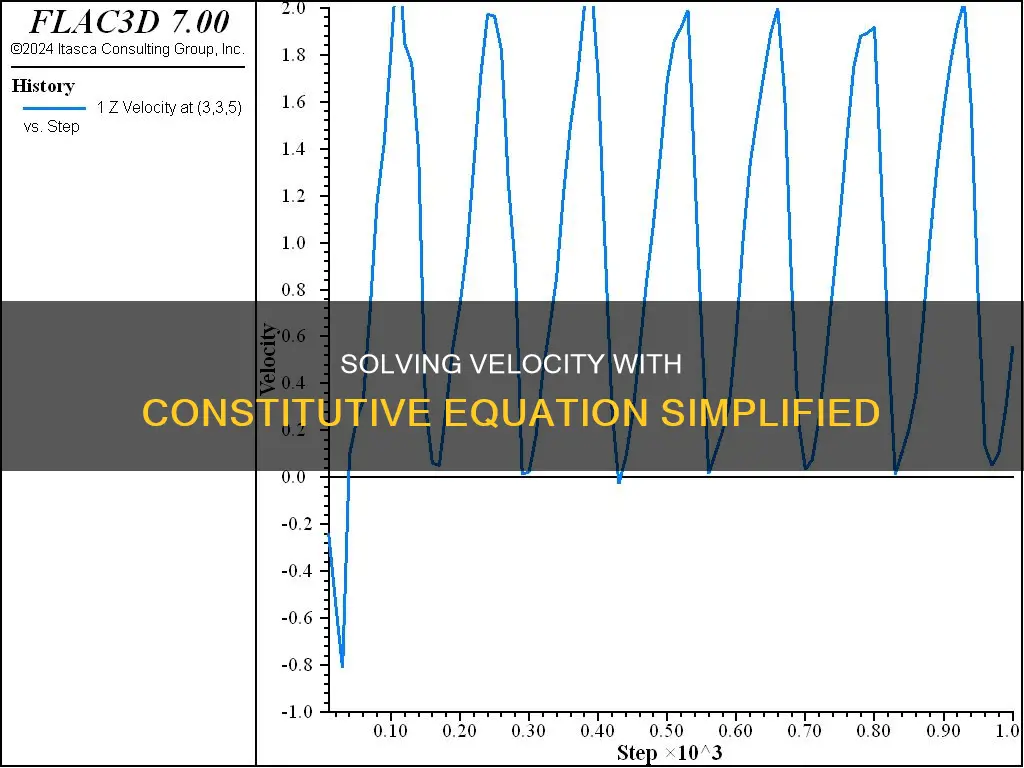

In fluid mechanics, velocity is a crucial parameter that helps us understand the behaviour of fluids in various systems. To solve for velocity, constitutive equations are often employed, providing a relationship between kinetic quantities (like velocity) and the physical properties of the fluid.

The constitutive equation, also known as a constitutive relation, is a fundamental concept in physics and engineering. It establishes a connection between two or more physical quantities, particularly kinetic quantities, and their corresponding kinematic quantities (such as strain or deformation). These equations are tailored to specific materials or substances, offering insights into how they respond to external influences like applied forces or fields.

In the context of fluid mechanics, constitutive equations are indispensable for comprehending fluid behaviour in pipes, channels, or other geometries. One of the most prominent equations in this field is the Navier-Stokes equation, which is pivotal in continuum mechanics. The Navier-Stokes equation mathematically expresses momentum balance for Newtonian fluids, accounting for the conservation of mass and the influence of viscosity. This equation is derived from the Cauchy equations, where the deviatoric (shear) stress tensor is expressed in relation to viscosity and the fluid velocity gradient.

The solution to the Navier-Stokes equations yields a flow velocity vector field. This vector field assigns a vector to every point in the fluid at any given moment, indicating the direction and magnitude of the fluid's velocity at that specific location and time. Studying velocity as a vector field is particularly relevant in fluid dynamics, as it offers a more meaningful representation compared to the classical mechanics approach of tracking particle positions.

It is worth noting that the Navier-Stokes equations have certain limitations. They are elliptic equations, which grants them favourable analytic attributes, but at the cost of reduced mathematical structure. Additionally, they exclusively pertain to Newtonian fluids, neglecting to account for more complex fluid behaviours. For instance, in the melt spinning of polyolefins, a viscoelastic model is recommended to accurately capture the behaviour at low take-up velocities.

In conclusion, solving for velocity in fluid mechanics relies on constitutive equations, with the Navier-Stokes equation being a central tool. However, the complexity of fluid behaviour often necessitates a range of specialised constitutive equations and complementary approaches to fully characterise fluid velocity and its underlying mechanisms.

War and Elections: A Dangerous Mix

You may want to see also

Velocity gradient in Newtonian fluids

Velocity gradient is a fundamental concept in fluid mechanics, which is a branch of physics that deals with the behaviour of liquids and gases and the forces acting upon them. It is particularly important when studying Newtonian fluids, which are fluids in which the viscous stresses at any point are linearly correlated to the local strain rate—the rate of change of its deformation over time.

The velocity gradient refers to the difference in velocity between the different layers of a fluid. When water flows through a pipe, for example, the layers of water in contact with the pipe walls are in a different motion from the layers in the centre. This variation in velocity between the layers is described as the velocity gradient. It is represented by v/x, where v stands for velocity and x stands for the distance between adjacent layers of the fluid.

Mathematically, the velocity gradient is defined as the derivative of velocity with respect to position. It can be represented as:

> \ \[ {\bf L} = {\partial {\bf v} \over \partial {\bf x} } = \left [ \matrix{ {\partial v_x \over \partial x} & {\partial v_x \over \partial y} & {\partial v_x \over \partial z} \\ \\ {\partial v_y \over \partial x} & {\partial v_y \over \partial y} & {\partial v_y \over \partial z} \\ \\ {\partial v_z \over \partial x} & {\partial v_z \over \partial y} & {\partial v_z \over \partial z} } \right ] \]

In the context of Newtonian fluids, the velocity gradient is closely related to the shear stress and strain rate. Newton's Law states that stress is proportional to strain, and this relationship is used to characterise Newtonian fluids. The shear stress is denoted by τ, and the fluid velocity gradient is represented by du/dy, where u is the velocity. The proportionality constant between them is defined as the dynamic viscosity (μ). Thus, for a Newtonian fluid, the shear stress is linearly related to the velocity gradient:

> τ ∝ du/dy

This relationship between shear stress and velocity gradient is valid for many common fluids under normal conditions, such as water, air, alcohol, and glycerol. However, it is important to note that real fluids may deviate from ideal Newtonian behaviour under extreme conditions or when the shear stress becomes very high.

The Process of Amending the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Velocity in nuclear thermal-hydraulics

Velocity, a "

In the field of nuclear thermal-hydraulics, velocity plays a crucial role in understanding the physics and mechanics of fluid flow and energetic transfer within complex systems such as nuclear reactors. The constitutive equation, a relation between physical quantities, is essential for modelling in two-phase nuclear thermal-hydraulics, especially for "unequal-velocity, unequal-temperature" (UVUT) models. These models are used to numerically simulate the phenomena in nuclear thermal-hydraulics, and the constitutive equations are derived from experiments.

The constitutive equation is combined with other equations that govern physical laws to solve problems related to fluid mechanics. In the context of nuclear thermal-hydraulics, this involves understanding the flow of fluids within the reactor and their interactions with the surrounding structures. For example, the Boiling Water Reactor Turbine Trip (BWRTT) Benchmark was established to challenge the coupled system thermal-hydraulic/neutron kinetics codes by simulating a sudden closure of the turbine stop valve.

Additionally, the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) has an Expert Group on Reactor Core Thermal-Hydraulics and Mechanics (EGTHM) that provides expert advice on the development of multi-scale core thermal-hydraulics modelling and simulation of nuclear reactor systems. They also maintain the International Experimental Thermal Hydraulics Systems (TIETHYS) database, which contains experimental data for validation and research purposes.

In summary, velocity is a critical parameter in nuclear thermal-hydraulics, and constitutive equations play a key role in modelling and understanding the complex behaviour of fluids within nuclear reactors.

The Constitution: Ensuring Public Order and Safety

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Velocity in thermoelasticity

In physics and engineering, a constitutive equation is a relation between two or more physical quantities, especially kinetic quantities as related to kinematic quantities. They are used to solve physical problems, such as fluid flow in a pipe or the response of a crystal to an electric field.

Velocity is a vector quantity that incorporates both magnitude and direction. It is calculated by dividing displacement by time, where displacement is the distance covered in a specific direction.

In the context of thermoelasticity, velocity is a crucial factor. Thermoelasticity deals with the behaviour of materials under non-isothermal conditions, exhibiting a linear stress-strain relation. The velocity of temperature and stress waves can control the time changes of stress strength terms, particularly during the early stages of a heat shock. For instance, the addition of graphene platelets to a polymer matrix increases the thermal wave velocity and alters the displacement and temperature distributions.

When considering the rotation, voids, and diffusion in a thermoelastic material, a velocity equation can be derived to study the propagation of plane waves in the medium. This equation indicates the propagation of five coupled plane waves in the medium.

Furthermore, in the context of nuclear thermal-hydraulics, constitutive equations are used to model unequal-velocity and unequal-temperature scenarios. These equations are derived from experiments and are used for numerical simulations.

The Electoral College: Branch Selection and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Velocity in plasticity theories

Velocity is defined as the rate at which displacement changes over time. In other words, velocity is displacement divided by time. In physics, velocity is considered a <"vector quantity", meaning it incorporates both magnitude and direction. On the other hand, speed is a "scalar quantity", which only deals with magnitude and not direction.

In the context of plasticity theories, velocity is a crucial factor in understanding the behaviour of materials under deformation. Flow plasticity theories, for instance, assume that the total strain in a body can be divided into an elastic part and a plastic part. The elastic part of the strain can be calculated using a linear elastic or hyperelastic constitutive model. However, determining the plastic part requires a flow rule and a hardening model.

In metal plasticity, the flow rule encapsulates the assumption that the plastic strain increment and the deviatoric stress tensor share the same principal directions. This relationship is expressed as:

> dϵp=dλ∙∂f∂σ

> dλ>0

This form of the flow rule is known as an associated flow rule, and the assumption of co-directionality is termed the normality condition.

Plasticity theories also encompass the study of friction, where plastic deformation plays a significant role in the frictional sliding of two bodies. However, classical plasticity theory has not been successfully applied to friction problems due to discrepancies with Coulomb's friction theory.

In certain applications, such as melt spinning of polymers, the use of a viscoelastic model is recommended to account for the complex behaviour of the material, even at extremely low take-up velocities.

Furthermore, large deformation flow theories of plasticity often begin with assumptions regarding the decomposition of the rate of deformation tensor into elastic and plastic components. This is exemplified in the following equation:

> L^p = ∂ ∙ F^p ∙ (F^p)^-1

Here, L^p represents the plastic velocity gradient, which is defined in an intermediate, stress-free configuration.

In summary, velocity is a critical parameter in plasticity theories, influencing our understanding of material behaviour, friction, and deformation. By employing constitutive equations and models, we can gain insights into the complex relationships between velocity, strain, and the mechanical properties of various materials.

Foundations of Freedom: Guarding Tyranny with the US Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The formula for velocity is velocity (v) = displacement (d) / time (t).

Speed is a "scalar quantity" that deals with magnitude but not direction, while velocity is a "vector quantity" that incorporates both magnitude and direction.

A constitutive equation is a mathematical expression that describes the relationship between two or more physical quantities, such as stress and strain within a material.

Constitutive equations can be used to understand the behaviour of fluids and their dynamics. For example, the constitutive equation for a fluid relates the force (stress) in the fluid to the rate of deformation (velocity gradient).

To solve for velocity, you would need to rearrange the formula to isolate velocity. For example, if you know the initial velocity, acceleration, and time, you can plug these values into the equation v = u + at to calculate the final velocity.