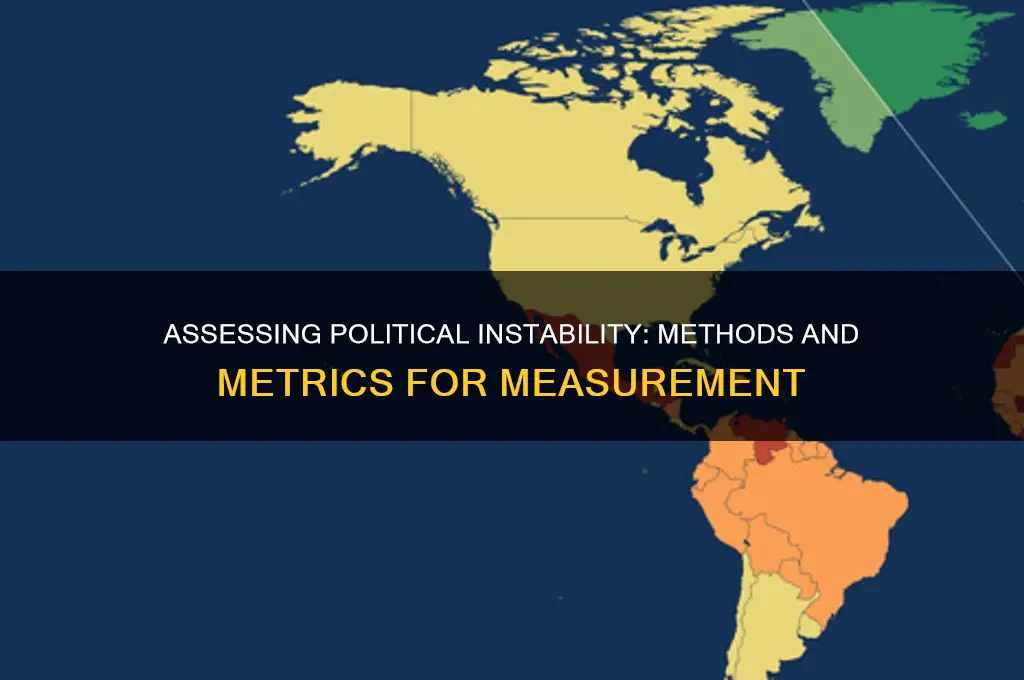

Measuring political instability is a complex yet crucial task for understanding the dynamics of governance, societal cohesion, and economic development. It involves assessing various indicators such as the frequency of government changes, levels of civil unrest, the prevalence of violent conflicts, and the erosion of democratic institutions. Scholars and analysts often rely on quantitative metrics, such as indices of political violence, electoral volatility, and state fragility, alongside qualitative assessments of governance quality and public trust in institutions. By combining these approaches, researchers can gauge the depth and breadth of instability, enabling policymakers to identify risks, allocate resources effectively, and implement strategies to foster stability and resilience in politically volatile environments.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Indicators: GDP fluctuations, inflation rates, unemployment levels reflect instability's impact on economies

- Conflict Metrics: Frequency of protests, riots, coups, and civil wars quantify political unrest

- Governance Quality: Corruption levels, rule of law, and government effectiveness measure stability

- Media Analysis: Sentiment in news, social media, and press freedom gauge public perception

- Election Volatility: Irregular elections, voter turnout, and leadership changes signal instability

Economic Indicators: GDP fluctuations, inflation rates, unemployment levels reflect instability's impact on economies

Political instability often leaves a visible mark on a nation's economic health, and this impact can be quantified through key economic indicators. Among these, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fluctuations serve as a critical barometer. A sudden drop in GDP growth rates or erratic fluctuations can signal underlying political turmoil. For instance, countries experiencing frequent government changes or policy reversals tend to exhibit volatile GDP trends. Investors and businesses crave predictability, and when political instability disrupts this, economic activity contracts. Analyzing GDP data over time, especially in comparison to regional peers, can reveal the extent to which political uncertainty has stifled economic growth.

Inflation rates provide another lens through which to view the economic consequences of political instability. In unstable environments, inflation often spirals out of control due to factors like supply chain disruptions, currency devaluation, and erratic monetary policies. Hyperinflation, a severe form of inflation, has historically been linked to political crises, as seen in Zimbabwe in the late 2000s. Monitoring inflation rates can thus offer early warnings of deepening political instability. Central banks in stable economies typically aim for a modest inflation rate (around 2-3%), and deviations from this target can indicate trouble. For practical analysis, economists often track core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, to better isolate the impact of political factors.

Unemployment levels further illustrate the economic toll of political instability. When governments fail to provide a stable environment, businesses hesitate to hire, and job creation stalls. Prolonged political uncertainty can lead to structural unemployment, where workers lack the skills needed for emerging industries due to neglected education and training policies. Youth unemployment, in particular, is a critical indicator, as it can fuel social unrest and further destabilize the political landscape. For instance, the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 were partly driven by high youth unemployment rates in countries like Tunisia and Egypt. Tracking unemployment data, especially disaggregated by age and sector, can provide actionable insights into the human cost of political instability.

To measure the impact of political instability on economies, a multi-indicator approach is essential. Start by examining GDP trends for volatility and compare them to historical benchmarks or regional averages. Pair this with inflation rate analysis, focusing on both headline and core inflation to distinguish between external shocks and policy-induced instability. Finally, scrutinize unemployment data, particularly youth unemployment, to gauge the social and economic strain. Caution should be exercised when interpreting these indicators in isolation, as external factors like global commodity prices or natural disasters can also influence them. However, when analyzed together, GDP fluctuations, inflation rates, and unemployment levels offer a robust framework for quantifying the economic fallout of political instability. This approach not only aids in understanding current conditions but also in forecasting potential risks and informing policy interventions.

Is Lloyd Polite Filipino? Unraveling the Singer's Cultural Background

You may want to see also

Conflict Metrics: Frequency of protests, riots, coups, and civil wars quantify political unrest

Political instability often manifests in overt conflict, making the frequency of protests, riots, coups, and civil wars critical metrics for assessment. These events, though varying in scale and intensity, serve as barometers of societal discontent and governmental fragility. Protests, for instance, can range from peaceful demonstrations to violent clashes, each signaling different levels of unrest. Riots escalate this tension, reflecting a breakdown in public order and often a deeper systemic issue. Coups and civil wars represent the most extreme forms of instability, indicating a collapse of political institutions and widespread violence. Tracking these events over time provides a quantitative foundation for understanding the depth and trajectory of political turmoil.

To measure these conflict metrics effectively, researchers and analysts rely on structured data collection and categorization. Databases like the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT) offer granular records of protests, riots, and armed conflicts worldwide. For example, ACLED categorizes events by type, location, and actor involvement, allowing for nuanced analysis. Coups and civil wars, though less frequent, are documented by organizations like the Center for Systemic Peace, which maintains datasets on political regimes and their transitions. Cross-referencing these sources ensures a comprehensive view of conflict frequency and its correlation with instability.

However, raw frequency alone is insufficient for meaningful analysis. Contextual factors such as population size, geographic spread, and the government’s response to unrest must be considered. For instance, a country with a large population may experience more protests without necessarily being more unstable than a smaller nation with fewer but more violent incidents. Similarly, a government’s tolerance for dissent can skew data—repressive regimes may suppress protests, leading to lower recorded frequencies despite underlying instability. Analysts must therefore triangulate conflict metrics with qualitative insights, such as media reports, expert assessments, and public sentiment analysis.

Practical applications of these metrics extend beyond academia. Policymakers use them to allocate resources, design interventions, and predict risks. For example, a sudden spike in protests or riots in a specific region might prompt targeted economic development programs or dialogue initiatives. International organizations like the United Nations leverage conflict data to deploy peacekeeping missions or humanitarian aid. Businesses, too, rely on these metrics to assess operational risks in volatile areas. By quantifying unrest, conflict metrics transform abstract instability into actionable intelligence, enabling proactive rather than reactive responses.

Despite their utility, conflict metrics are not without limitations. They capture visible manifestations of instability but may overlook underlying causes, such as economic inequality or ethnic tensions. Additionally, data collection biases—whether due to censorship, underreporting, or methodological inconsistencies—can distort findings. To mitigate these challenges, analysts should complement quantitative data with qualitative research, such as interviews, surveys, and historical analysis. Only by integrating multiple perspectives can conflict metrics provide a holistic understanding of political instability and inform effective strategies for mitigation.

India's Political Stability: Strengths, Challenges, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Governance Quality: Corruption levels, rule of law, and government effectiveness measure stability

Political instability often stems from weak governance, making the quality of governance a critical metric for assessing stability. Three key indicators—corruption levels, rule of law, and government effectiveness—provide a comprehensive lens to evaluate this. High corruption erodes public trust, distorts resource allocation, and undermines institutions, creating fertile ground for unrest. The rule of law, or its absence, signals whether a society operates on fairness and predictability or is prone to arbitrary power and conflict. Government effectiveness, meanwhile, reflects the state’s capacity to deliver public goods, manage crises, and enforce policies, all of which are essential for maintaining order. Together, these factors offer a nuanced view of a nation’s stability, revealing vulnerabilities before they escalate into full-blown crises.

To measure governance quality, analysts often turn to standardized indices like the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI). These tools quantify corruption levels through metrics such as bribery frequency, embezzlement rates, and transparency in public procurement. For instance, a country with a corruption perception index score below 30 (on a scale of 0 to 100) is likely to face significant political instability. Similarly, the rule of law is assessed via indicators like judicial independence, contract enforcement, and crime rates. A nation where courts are perceived as biased or contracts are rarely honored will struggle to maintain stability. Government effectiveness is gauged by its ability to formulate and implement policies, manage public resources, and respond to citizen needs. A government that consistently fails in these areas risks losing legitimacy and sparking discontent.

Consider the case of a hypothetical country, *Zambia*, where corruption is rampant, the judiciary is influenced by political elites, and public services are chronically underfunded. Citizens, frustrated by inequality and inefficiency, may resort to protests or even violence. In contrast, *Estonia*, with its low corruption rates, robust legal framework, and efficient e-governance systems, exemplifies stability. These examples illustrate how governance quality directly correlates with political stability. By focusing on these three indicators, policymakers and researchers can identify systemic weaknesses and implement targeted reforms to mitigate instability.

However, measuring governance quality is not without challenges. Data collection can be biased, especially in authoritarian regimes where transparency is limited. Additionally, cultural differences may skew perceptions of corruption or rule of law. For instance, gift-giving in some cultures may be misinterpreted as bribery. To address these limitations, it’s essential to triangulate data from multiple sources, including surveys, administrative records, and expert assessments. Practical tips for improving governance quality include strengthening anti-corruption agencies, investing in judicial training, and leveraging technology for transparent service delivery. By adopting a multi-faceted approach, nations can enhance governance quality and, in turn, bolster political stability.

Ultimately, governance quality serves as both a diagnostic tool and a roadmap for stability. Corruption, rule of law, and government effectiveness are not isolated factors but interconnected pillars of a functioning state. Ignoring weaknesses in one area can destabilize the entire system. For instance, a government that prioritizes economic growth at the expense of judicial independence may achieve short-term gains but sow long-term instability. Conversely, nations that consistently improve governance quality—such as Georgia’s post-2003 anti-corruption reforms—often experience increased stability and citizen trust. By focusing on these three indicators, stakeholders can not only measure instability but also take proactive steps to prevent it, ensuring a more resilient political environment.

Faith and Governance: A Christian's Guide to Navigating Political Engagement

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$84.99 $99.99

Media Analysis: Sentiment in news, social media, and press freedom gauge public perception

Public sentiment, as reflected in media, serves as a real-time barometer of political instability. News outlets, social media platforms, and press freedom indices collectively paint a picture of societal mood, which can foreshadow or confirm turmoil. For instance, a sudden spike in negative sentiment across multiple platforms—characterized by keywords like "protest," "corruption," or "crisis"—often correlates with brewing instability. Analyzing these trends requires tools like natural language processing (NLP) to quantify sentiment and identify patterns. However, raw data alone is insufficient; context matters. A region with historically polarized media may normalize extreme rhetoric, making it essential to benchmark against local baselines.

To effectively gauge public perception through media analysis, follow these steps: First, collect data from diverse sources, including mainstream news, Twitter, Facebook, and local forums. Second, employ sentiment analysis tools (e.g., VADER for social media, LexisNexis for news) to categorize content as positive, negative, or neutral. Third, cross-reference findings with press freedom rankings from organizations like Reporters Without Borders to assess whether media suppression skews results. For example, a country with low press freedom may show artificially positive sentiment due to censorship, while a free press might amplify dissent. Finally, track changes over time—a consistent decline in positive sentiment or a surge in negative mentions of government officials can signal growing instability.

A comparative approach highlights the nuances of media sentiment across regions. In countries with high press freedom, like Norway, negative sentiment often reflects healthy debate rather than instability. Conversely, in authoritarian regimes, even minor deviations from positive sentiment can indicate suppressed discontent. Social media plays a unique role here: platforms like Twitter are less censored than traditional media, making them a more reliable indicator in repressive environments. However, their echo chamber effect can exaggerate sentiment, requiring triangulation with other sources. For instance, during the Arab Spring, Twitter sentiment turned sharply negative weeks before mainstream media caught up, but ground reports were essential to validate the scale of unrest.

Despite its utility, media sentiment analysis has pitfalls. Overreliance on automated tools can misread sarcasm or cultural nuances, leading to false positives. For example, in India, the phrase "acche din" (good days) was used sarcastically during economic hardship, confusing algorithms. Additionally, bot activity on social media can artificially inflate sentiment, as seen in the 2016 U.S. election. To mitigate these risks, incorporate human review and focus on trends rather than isolated spikes. Pair sentiment analysis with qualitative methods, such as expert interviews or focus groups, to deepen understanding. Practical tip: Use dashboards like Brandwatch or Hootsuite to monitor sentiment in real-time, but always verify anomalies through multiple channels.

In conclusion, media analysis offers a dynamic lens to measure political instability, but it demands rigor and nuance. By combining sentiment tracking with press freedom metrics and contextual awareness, analysts can distinguish between fleeting discontent and systemic instability. For policymakers, this approach provides early warnings, while researchers gain insights into public opinion’s role in political upheaval. The key takeaway? Media sentiment is not a crystal ball, but a thermometer—its readings are most valuable when interpreted within a broader framework of political, social, and historical context.

Is Hermaphrodite a Polite Term? Understanding Respectful Language for Intersex Individuals

You may want to see also

Election Volatility: Irregular elections, voter turnout, and leadership changes signal instability

Election volatility serves as a critical barometer of political instability, with irregular elections, fluctuating voter turnout, and frequent leadership changes acting as red flags. Irregular elections, whether delayed, canceled, or manipulated, disrupt democratic norms and erode public trust. For instance, in countries like Venezuela and Zimbabwe, elections have been postponed or rigged, signaling authoritarian tendencies and systemic fragility. Such deviations from established electoral calendars often correlate with broader governance issues, including corruption and human rights abuses. Monitoring election schedules and their adherence to legal frameworks provides a quantifiable metric for assessing instability.

Voter turnout, another key indicator, reflects civic engagement and the health of democratic institutions. A sharp decline in participation, as seen in recent elections in France and the United States, can indicate disillusionment or polarization. Conversely, sudden spikes in turnout, particularly in regions with historical apathy, may suggest mobilization driven by crisis or populist movements. Analysts should track turnout trends across demographic groups and regions, using deviations from historical averages to identify potential instability. For practical application, election observers can employ tools like the Electoral Integrity Project’s dataset to benchmark turnout patterns against global standards.

Leadership changes, especially those occurring outside constitutional processes, are a direct measure of political volatility. Frequent cabinet reshuffles, coups, or resignations under pressure destabilize governance and create uncertainty. For example, Italy’s 66 governments since 1945 highlight chronic instability, while Thailand’s repeated military interventions underscore systemic fragility. To measure this, researchers can use indices like the World Bank’s Political Stability and Absence of Violence index, which tracks leadership transitions and their contexts. Pairing this data with media sentiment analysis can provide real-time insights into public perception of leadership changes.

The interplay of these factors—irregular elections, voter turnout, and leadership changes—offers a comprehensive framework for measuring instability. For instance, a country with delayed elections, plummeting turnout, and frequent leadership shifts likely faces deeper structural issues. Policymakers and analysts should cross-reference these indicators with economic and social data to identify root causes. Practical steps include establishing early warning systems that flag anomalies in election timelines, turnout rates, and leadership stability. By focusing on these specific metrics, stakeholders can proactively address instability before it escalates into crisis.

Honoring Political Volunteers: Meaningful Ways to Show Gratitude and Appreciation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Key indicators include frequency of government changes, incidence of coups or revolutions, levels of political violence, protests, and civil unrest, as well as measures of state fragility and institutional weakness.

Economic factors like high unemployment, inflation, income inequality, and poverty often correlate with political instability, as they can fuel public discontent and erode trust in government.

Yes, political instability can be quantified using datasets such as the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) index, the Fragile States Index, or measures of democratic backsliding and governance quality.

Media coverage can highlight events like protests, government crackdowns, or political scandals, providing qualitative insights into instability, though it may be biased or incomplete.

Political instability varies based on factors like historical context, governance structures, socioeconomic conditions, and external influences, making it essential to analyze each case individually.