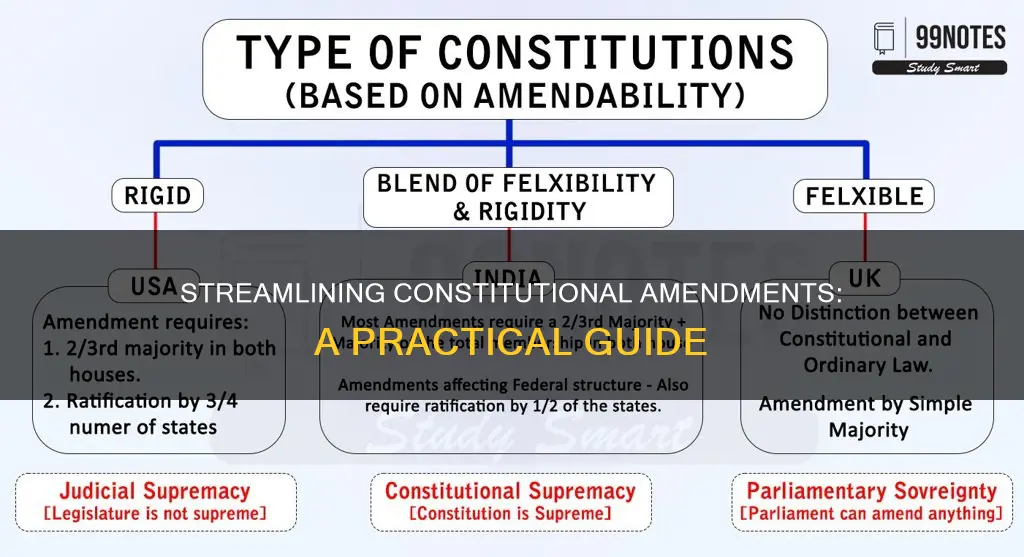

The process of amending the US Constitution is difficult and time-consuming. Since it was drafted in 1787, there have only been 27 amendments, with none proposed by constitutional convention. The process requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House and the Senate, or two-thirds of state legislatures requesting a constitutional convention. The high bar for constitutional change has led to proposals for making the amendment process easier, such as lowering the threshold for change or changing the order of operations. However, this presents a paradox: how can the amendment process be changed if amending the Constitution is seemingly impossible? Some suggest that giving state legislatures more power to propose amendments would make it easier to get good ideas on the table and assess their support, while retaining the tough voting rules of Article V would prevent bad ideas from passing.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Difficulty in amending the Constitution | High bar for constitutional change |

| Interpretations of Article V | The Supreme Court's interpretation of Article V disempowers voters in the federal amendment process |

| Polarized politics | Consensus for constitutional change is difficult to obtain |

| Role of state legislatures | State legislatures play a key role in three out of four potential paths for constitutional change |

| Role of Congress | Congress proposes amendments and chooses the ratifier |

| Role of the Archivist | The Archivist of the United States administers the ratification process |

| Role of the OFR | The OFR examines ratification documents for facial legal sufficiency and authenticating signatures |

| Ratification by states | An amendment becomes part of the Constitution when ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50) |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

Make the process less polarising

In an era of hyper-polarised politics, achieving the profound consensus required for constitutional reform is nearly impossible. The amendment process in the Constitution can be made less polarising by implementing the following strategies:

Firstly, it is essential to recognise the root causes of the issue. The difficulty in amending the Constitution stems not only from the text of Article V, which outlines the amendment process, but also from its interpretation. Over a century ago, the Supreme Court's ruling in Hawke v. Smith disempowered voters in the federal amendment process, vesting state legislatures with significant authority. This interpretation has contributed to the polarising nature of the amendment process.

To address this, it is crucial to re-evaluate and reinterpret Article V in a way that empowers voters and reduces the influence of state legislatures. This could involve enabling voters to bypass state legislatures and directly apply for a constitutional convention, ratifying popular amendment proposals, and rejecting unpopular ones. By involving voters more directly, the amendment process can become more representative of the people's will and less susceptible to the polarising influences of state legislatures.

Additionally, flipping the current amendment process on its head by allowing individual states to take the initiative can help alleviate polarisation. Each state could propose amendments and evaluate the proposals of other states. Once three-quarters of the state legislatures agree on the wording, the proposal would then be sent to Congress for ratification, requiring a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate. This approach would foster collaboration and consensus-building among states, reducing the polarising impact of partisan politics at the national level.

Furthermore, it is important to maintain the high bar for constitutional change set by Article V while also streamlining the amendment process. This can be achieved by ensuring that any proposed amendment secures broad support across the country. Rather than solely relying on politicians, engaging a diverse range of stakeholders, including legal experts, community leaders, and grassroots organisations, can help build consensus and mitigate the polarising effects of partisan politics.

Lastly, it is worth considering constitutional reform that addresses the root causes of polarisation. For instance, electoral reforms that reduce the disproportionate influence of smaller states or promote a more proportional representation system could lead to a more balanced and representative political landscape. While these reforms may not directly alter the amendment process, they can contribute to a less polarised political environment, making it easier to achieve the consensus needed for constitutional changes.

The Mini Constitution: A Powerful Amendment

You may want to see also

Empower voters to bypass state legislatures

The process of amending the US Constitution is a complex and lengthy one. It involves a proposal by Congress with a two-thirds majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, followed by ratification by three-fourths of the States. While the President does not have a direct role in this process, it is worth noting that none of the 27 amendments to the Constitution thus far have been proposed by a constitutional convention, which is an alternative route to initiating amendments. This involves two-thirds of state legislatures requesting that Congress call such a convention, though this has never occurred.

The current process gives state legislatures a significant role, which can sometimes lead to delays or even the blocking of amendments. To empower voters to bypass state legislatures, a system of direct democracy could be implemented, giving citizens a more direct say in public policy and constitutional amendments. This system already exists in some states, where citizens can use the popular referendum process to repeal specific statutes passed by the state legislature. This process, also known as a veto referendum, citizen referendum, or statute referendum, allows citizens to place a measure on the ballot to repeal a statute.

In addition to the popular referendum, some states also have a legislative referendum, where the state legislature proposes a statute or constitutional amendment that requires voter approval. This process involves the state legislature placing a proposed statute or amendment on the ballot, giving voters the final say. Another variation is the advisory referendum, where states and localities can pose non-binding questions to gauge voters' opinions. This type of referendum is rarely used but provides a way for voters to provide input without officially bypassing the state legislature.

A more direct way to empower voters to bypass state legislatures is through the direct initiative process, currently in use in 19 states. This process allows citizens to place proposed statutes or constitutional amendments directly on the ballot for voter approval, completely circumventing the state legislature. This system of direct democracy gives citizens a more direct role in shaping public policy and can be a powerful tool for effecting change at the state level.

By implementing and expanding these direct democracy mechanisms, voters can have a more direct impact on the amendment process and policy-making in general. These tools provide a means to address corruption, ensure that the voices of citizens are heard, and potentially streamline the process of enacting constitutional amendments.

Amendments to North Dakota's Constitution: A Historical Overview

You may want to see also

Propose amendments via constitutional convention

The United States Constitution, drafted in 1787, has been amended only 27 times. The authority to amend the Constitution is derived from Article V of the Constitution, which outlines two methods for proposing amendments. One of these methods is through a constitutional convention, also referred to as an Article V Convention, state convention, or amendatory convention.

A constitutional convention for proposing amendments can be called upon the application of two-thirds of the state legislatures (34 out of 50). This method has never been used; all 27 amendments to date have been proposed by a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of Congress.

At the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, eight state constitutions included an amendment mechanism. The Articles of Confederation, which required unanimous consent of all 13 states for the national government to take action, were considered unworkable. The Virginia Plan, proposed during the 1787 Convention, sought to bypass the national legislature, stating that "the assent of the National Legislature ought not to be required." This was later modified to include a process whereby Congress would call for a constitutional convention upon the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures.

George Mason argued that requiring the consent of the National Legislature would be improper, as they may abuse their power and refuse consent. He further stated that "no amendments of the proper kind would ever be obtained by the people, if the Government should become oppressive."

In 1949, six states applied for a convention to propose an amendment to enable the participation of the United States in a world federal government. Since the late 1960s, there have been two nearly successful attempts to amend the Constitution via an Article V Convention.

While a constitutional convention for proposing amendments has never been convened at the federal level, more than 230 constitutional conventions have assembled at the state level.

Amendments: Shaping the Constitution and Our Rights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Retain tough voting rules, but enable more written amendments

The process of amending the US Constitution is notoriously difficult. Since the Constitution was drafted in 1787, it has only been amended 27 times. The current process requires a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures. This high bar for constitutional change has led to a backlog of proposed amendments, with many "dead on arrival".

One suggestion to improve the amendment process is to retain the tough voting rules of Article V but enable more written amendments by allowing individual states to take the lead. This would mean that states could propose amendments and assess the proposals of others. Once three-quarters of state legislatures agree on a proposal, it would then be sent to Congress, where the same two-thirds majority would be required to ratify. This approach, known as "flipping Article V", would make it easier to get good ideas on the table and work out their problems, without lowering the bar for constitutional change.

Flipping Article V would not guarantee that every good amendment is passed or every bad one rejected, but it would address the current system's overreliance on national politicians, who often oppose each other reflexively. It would also empower states to have a more direct say in the amendment process, which could help to mitigate the disproportionate influence of smaller states.

However, there are potential drawbacks to this approach. Firstly, it could lead to a more fragmented and inconsistent amendment process, with states working in isolation rather than collaborating to find consensus. Secondly, it may still struggle to gain traction in a highly polarized political climate, where even proposals with broad support can falter.

Despite these challenges, flipping Article V offers a potential solution to improving the amendment process by retaining tough voting rules while enabling a broader range of written amendments to be considered.

The Fourth Amendment: A Year of Change

You may want to see also

Make the process easier, but don't lower standards

The process of amending the US Constitution is notoriously difficult. Since the Constitution was drafted in 1787, it has only been amended 27 times. The process is intentionally challenging and time-consuming, requiring a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures.

Some argue that the process needs to be made easier to facilitate necessary changes. However, this should not come at the cost of lowering standards. One proposal to streamline the process without compromising on quality is to allow individual states to take the lead. This would enable states to propose amendments, work through their challenges, and gauge their level of support. This approach, known as "flipping Article V," would still require a two-thirds approval from Congress, ensuring that the amendment has broad support across the country.

Flipping Article V would not guarantee the passage of every good amendment or the rejection of every bad one. However, it would increase the chances of beneficial amendments being written and proposed. This method would also retain the tough voting rules outlined in Article V, which stipulates the process for proposing and ratifying amendments. By involving state legislatures in the initial stages, more ideas could be brought to the table, and their merits could be thoroughly evaluated.

Additionally, flipping Article V would address the issue of political polarization. Currently, when one set of national politicians supports an amendment, it is often automatically opposed by another group, causing most proposals to fail from the outset. By starting at the state level, amendments would have a better chance of gaining bipartisan support and overcoming the deep political divisions that often hinder progress at the national level.

While making the amendment process more accessible is essential, maintaining the high standards set by the Constitution is crucial. By empowering states to initiate the process, the US can strike a balance between adaptability and upholding the integrity of the nation's founding document.

First Amendment: Media's Constitutional Cornerstone

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Constitution has been amended only 27 times since 1787. The current process to amend the Constitution is very difficult and time-consuming. A proposed amendment must be passed by two-thirds of both houses of Congress and then ratified by three-fourths of the states (38 out of 50).

In an age of hyper-polarized politics, it is challenging to obtain the deep consensus required for constitutional change. The process requires support that is broadly distributed across the country. Anything favoured by one set of national politicians is often opposed by another, resulting in most amendment proposals being dead on arrival.

One suggestion is to let state legislatures propose amendments, which would make it easier to get good ideas on the table and assess their relative degree of support. Retaining Article V's tough voting rules would keep it difficult for bad ideas to get through. Additionally, voters could bypass state legislatures and ratify popular amendment proposals without legislative interference.