Defining the political spectrum is a complex yet essential task for understanding the diverse ideologies and beliefs that shape political systems worldwide. At its core, the political spectrum is a conceptual framework used to categorize political positions, typically along a left-right axis, though multidimensional models are increasingly recognized. The left is often associated with progressive, egalitarian, and collectivist ideals, emphasizing social justice, wealth redistribution, and government intervention to ensure equality. Conversely, the right tends to align with conservative, individualist, and free-market principles, prioritizing personal responsibility, limited government, and traditional values. However, this binary framework oversimplifies the nuances of political thought, as it fails to account for libertarian, authoritarian, populist, or environmentally focused ideologies that do not neatly fit within the left-right divide. Thus, defining the political spectrum requires a more nuanced approach, considering historical context, cultural differences, and the evolving nature of political ideologies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Left vs. Right: Origins, core values, and historical evolution of the traditional political spectrum

- Authoritarian vs. Libertarian: Measuring government control versus individual freedom across ideologies

- Economic Dimensions: Capitalism, socialism, and mixed economies as spectrum determinants

- Social Dimensions: Cultural progressivism vs. conservatism in shaping political positions

- Alternative Models: Beyond left-right: horseshoe theory, multidimensional spectra, and global variations

Left vs. Right: Origins, core values, and historical evolution of the traditional political spectrum

The traditional political spectrum, often visualized as a linear scale from Left to Right, traces its origins to the seating arrangement in the French National Assembly during the 1789 Revolution. Deputies favoring radical change sat on the left, while those supporting tradition and monarchy sat on the right. This spatial division became a metaphor for broader ideological differences, shaping how we categorize political beliefs today. Understanding this spectrum requires examining its historical roots, core values, and evolution, as it remains a foundational framework for political discourse.

At their core, Left-wing ideologies prioritize equality, collective welfare, and progressive change. Historically, the Left emerged as a response to industrialization and social inequality, advocating for workers’ rights, wealth redistribution, and government intervention to ensure social justice. Core values include economic egalitarianism, public ownership of resources, and the protection of marginalized groups. For instance, socialism and communism, both Left-wing ideologies, emphasize the abolition of class distinctions and the establishment of a society where resources are shared equitably. These principles often manifest in policies like universal healthcare, progressive taxation, and labor protections.

In contrast, Right-wing ideologies emphasize individual liberty, tradition, and hierarchical structures. The Right historically defended established institutions, private property, and free markets, viewing them as essential for stability and prosperity. Core values include limited government intervention, national identity, and the preservation of cultural norms. Conservatism, a dominant Right-wing ideology, seeks to maintain existing social orders and resist rapid change. For example, Right-wing policies often promote lower taxes, deregulation, and strong national defense, reflecting a belief in personal responsibility and market-driven solutions.

The historical evolution of the Left-Right spectrum reflects shifting global contexts. In the 19th century, the Left was synonymous with revolutionary movements against monarchies, while the Right defended aristocratic privileges. By the 20th century, the spectrum adapted to address new challenges, such as fascism, communism, and decolonization. Post-Cold War, the Left and Right redefined themselves, with the Left embracing social liberalism and the Right focusing on economic neoliberalism. Today, the spectrum is increasingly challenged by issues like globalization, climate change, and identity politics, which do not always fit neatly into traditional Left-Right categories.

To navigate the Left-Right spectrum effectively, consider its limitations. While it provides a useful starting point for understanding political differences, it oversimplifies complex ideologies and ignores cross-cutting issues. For instance, both Left and Right can advocate for environmental protection, albeit through different means. Practical tip: When analyzing political positions, ask how they balance equality and liberty, and whether they prioritize tradition or progress. This nuanced approach helps avoid reductive thinking and fosters a more informed political dialogue.

Is Politeness Perpetuating Prejudice? Exploring the Intersection of Racism and Etiquette

You may want to see also

Authoritarian vs. Libertarian: Measuring government control versus individual freedom across ideologies

The political spectrum often simplifies complex ideologies into a left-right scale, but the tension between authoritarianism and libertarianism offers a more nuanced lens. Authoritarian regimes prioritize collective stability and order, often at the expense of individual freedoms. Think of China’s surveillance state or North Korea’s tightly controlled society. In contrast, libertarian philosophies champion personal autonomy, minimizing government intervention in economic and social life. Examples include the laissez-faire capitalism of 19th-century America or modern libertarian movements advocating for deregulation and privacy rights. This dichotomy isn’t just theoretical—it shapes policies, from healthcare to national security, and influences how societies balance security with liberty.

To measure this spectrum, consider the degree of government control over daily life. Authoritarian systems often employ censorship, strict laws, and centralized decision-making. For instance, in authoritarian regimes, media outlets are state-controlled, and dissent is swiftly punished. Libertarians, however, argue that such control stifles innovation and individuality. They advocate for decentralized power, where individuals make choices free from government interference. A practical example is gun control: authoritarians might ban firearms for public safety, while libertarians view ownership as a fundamental right. The key question here is: where does the line between protection and oppression lie?

Analyzing this spectrum requires examining specific policies. Take taxation, for instance. Authoritarian regimes often impose high taxes to fund expansive social programs, ensuring uniformity but limiting personal wealth accumulation. Libertarians counter that lower taxes empower individuals to allocate resources as they see fit. Similarly, in education, authoritarians might mandate standardized curricula to maintain ideological consistency, while libertarians prefer school choice and parental control. These examples illustrate how the authoritarian-libertarian divide manifests in everyday governance, offering a framework to evaluate ideologies beyond traditional left-right labels.

A persuasive argument for understanding this spectrum is its relevance to global challenges. In times of crisis, such as pandemics or economic downturns, societies often swing toward authoritarian measures for quick stability. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and mandatory vaccinations are tools of control that libertarians would likely oppose as infringements on personal freedom. Yet, the libertarian ideal of absolute freedom can lead to chaos, as seen in unregulated markets or public health crises. Striking a balance requires recognizing that neither extreme is sustainable. Societies must navigate this spectrum, adapting policies to context while safeguarding core freedoms.

In conclusion, the authoritarian-libertarian axis provides a practical tool for dissecting political ideologies. By focusing on government control versus individual freedom, it reveals the trade-offs inherent in any system. Whether you lean toward order or autonomy, understanding this spectrum helps in crafting policies that respect both collective needs and personal rights. The challenge lies in avoiding the pitfalls of either extreme—ensuring that governments protect without oppressing and that individuals thrive without undermining societal stability. This framework isn’t just academic; it’s a roadmap for building equitable, functional societies.

NATO's Political Role: Alliance or Military Partnership?

You may want to see also

Economic Dimensions: Capitalism, socialism, and mixed economies as spectrum determinants

Economic systems serve as the backbone of political ideologies, shaping how societies allocate resources, distribute wealth, and organize production. Capitalism, socialism, and mixed economies are not rigid categories but points on a spectrum, with nations blending elements of each to varying degrees. Understanding this continuum requires examining the role of private ownership, government intervention, and market dynamics in determining a country’s economic identity. For instance, the United States leans toward capitalism with its emphasis on free markets, while Sweden exemplifies a mixed economy, balancing private enterprise with robust social welfare programs.

To map this spectrum, start by identifying the core principles of each system. Capitalism prioritizes private ownership and minimal government interference, fostering competition and innovation but often exacerbating inequality. Socialism, in contrast, advocates for collective or public ownership of resources, aiming to reduce disparities but sometimes stifling economic dynamism. Mixed economies occupy the middle ground, combining market-driven growth with state regulation and social safety nets. A practical exercise is to analyze how countries like Germany or Canada blend these elements, such as allowing private businesses to thrive while maintaining universal healthcare.

When evaluating a nation’s position on this spectrum, consider key indicators: the extent of government spending as a percentage of GDP, the prevalence of state-owned enterprises, and the robustness of labor protections. For example, a country with 50% of its GDP derived from government spending likely leans toward socialism, while one with 30% suggests a mixed economy. However, caution is necessary; labels like “capitalist” or “socialist” often oversimplify complex realities. Singapore, for instance, is capitalist in its market orientation but maintains significant state control over housing and investment, defying easy categorization.

Persuasively, the spectrum’s value lies in its ability to highlight trade-offs. Capitalism’s efficiency and innovation come at the cost of inequality, while socialism’s equity can hinder growth. Mixed economies aim to strike a balance, but their success depends on implementation. Policymakers must navigate this tension, as seen in France’s efforts to reform labor laws while preserving its welfare state. For individuals, understanding this spectrum fosters informed political engagement, enabling critiques of policies like tax cuts or nationalization based on their alignment with economic principles.

In conclusion, the economic dimension of the political spectrum is not a binary choice but a nuanced gradient. By dissecting the interplay of capitalism, socialism, and mixed economies, one gains a tool to analyze and predict political outcomes. Whether advocating for deregulation or public ownership, recognizing where a policy falls on this spectrum is essential for meaningful dialogue and effective governance.

Is 'Blacks' Politically Incorrect? Exploring Language and Sensitivity

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Social Dimensions: Cultural progressivism vs. conservatism in shaping political positions

Cultural progressivism and conservatism are not mere labels but powerful forces that shape how individuals and societies navigate the complexities of social change. At their core, these ideologies reflect divergent attitudes toward tradition, innovation, and the pace of societal evolution. Progressives tend to embrace change, advocating for the adaptation of cultural norms to reflect contemporary values such as diversity, inclusivity, and individual freedom. Conservatives, on the other hand, often prioritize preserving established traditions, viewing them as foundational to social stability and moral order. This tension between progress and preservation is a driving factor in political positions, influencing policies on issues like gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, immigration, and religious expression.

Consider the debate over same-sex marriage, a quintessential example of how cultural progressivism and conservatism manifest in political discourse. Progressives argue that legalizing same-sex marriage is a matter of equality and human rights, aligning with the evolving understanding of personal freedom. Conservatives, however, may frame opposition as a defense of traditional family structures and religious values. This clash illustrates how deeply social dimensions are intertwined with political ideologies. To analyze such issues effectively, it’s crucial to examine the underlying values each side prioritizes—whether it’s the progressive emphasis on inclusivity or the conservative focus on continuity.

When navigating these social dimensions, it’s instructive to adopt a comparative lens. For instance, compare how progressive and conservative societies handle immigration. Progressive nations often implement policies that prioritize multiculturalism and integration, viewing diversity as a strength. Conservative societies may favor stricter immigration controls, emphasizing cultural homogeneity and national identity. These approaches are not inherently right or wrong but reflect differing priorities. To engage constructively in these debates, focus on understanding the rationale behind each position rather than dismissing opposing views outright.

A persuasive argument for balancing progressivism and conservatism lies in recognizing their complementary roles. While progressivism drives necessary societal advancements, conservatism acts as a safeguard against unchecked change, ensuring that new ideas are grounded in ethical and practical considerations. For example, progressive movements have pushed for environmental regulations, but conservative principles of fiscal responsibility can temper these policies to ensure economic sustainability. This dynamic interplay highlights the importance of integrating both perspectives to create balanced and effective political solutions.

In practical terms, individuals can apply these insights by assessing their own positions on social issues through a dual lens. Ask yourself: Am I prioritizing innovation or preservation? How do my views align with broader societal values? For instance, if you support progressive policies like gender-neutral bathrooms, consider how these align with your beliefs about individual autonomy. Conversely, if you lean conservative on issues like religious expression in public spaces, reflect on how tradition informs your stance. By consciously examining these dimensions, you can develop a more nuanced understanding of your political positions and engage more thoughtfully in public discourse.

Is 'Do You Mind' Polite? Exploring Etiquette and Social Nuances

You may want to see also

Alternative Models: Beyond left-right: horseshoe theory, multidimensional spectra, and global variations

The traditional left-right political spectrum, while useful, often oversimplifies the complex landscape of political ideologies. Alternative models have emerged to capture the nuances that fall outside this binary framework. One such model is the horseshoe theory, which posits that the far-left and far-right, despite appearing opposite, share more similarities than differences. Both extremes, for instance, often reject liberal democracy, embrace authoritarianism, and prioritize collective identity over individual rights. Consider the historical parallels between communist and fascist regimes: both suppressed dissent, controlled media, and enforced rigid social hierarchies. This theory challenges the linear spectrum, suggesting a curved model where extremes converge. However, critics argue it risks equating disparate ideologies and ignores the unique dangers each poses.

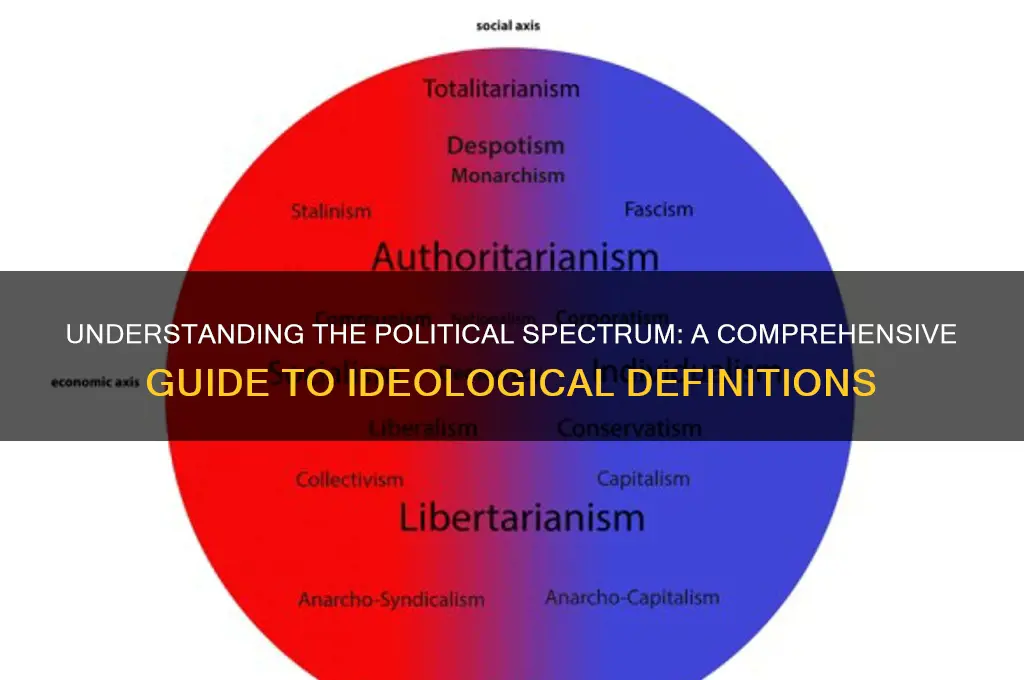

Another approach to redefining the political spectrum is through multidimensional models, which acknowledge that politics cannot be reduced to a single axis. These models introduce additional dimensions, such as authoritarianism vs. libertarianism or globalism vs. nationalism, to map ideologies more accurately. For example, the Political Compass uses a two-axis grid to differentiate between economic and social attitudes, placing libertarian capitalism and state socialism on one axis and social freedom vs. control on the other. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of ideologies like libertarian socialism or socially conservative liberalism, which the left-right spectrum struggles to categorize. Practical applications include voter profiling and policy analysis, enabling more precise targeting of political messaging.

Global variations further complicate the left-right paradigm, as political ideologies are deeply influenced by cultural, historical, and regional contexts. In India, for instance, the spectrum is shaped by caste politics, religious nationalism, and post-colonial identity, making it distinct from Western models. Similarly, in Latin America, the left-right divide often revolves around issues of economic inequality, anti-imperialism, and indigenous rights, rather than the social liberalism vs. conservatism debates prevalent in Europe. To navigate these differences, it’s essential to study local political histories and avoid imposing Western frameworks universally. For researchers and analysts, incorporating regional specifics into spectrum models enhances accuracy and relevance.

While alternative models offer richer insights, they are not without limitations. Horseshoe theory, for instance, risks oversimplifying the ideological spectrum by conflating distinct extremes. Multidimensional models, though more comprehensive, can become unwieldy and difficult to visualize or communicate. Global variations highlight the need for context-specific analysis but complicate cross-cultural comparisons. To maximize utility, practitioners should combine these models judiciously, tailoring them to the specific question or region at hand. For example, a multidimensional approach might be ideal for analyzing domestic policy, while a regionally adapted spectrum is better suited for international relations. Ultimately, the goal is not to replace the left-right spectrum but to complement it with tools that capture the full complexity of political thought.

Satire's Sharp Edge: Strengthening Democracy Through Humor and Critique

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The political spectrum is a conceptual framework used to categorize and compare political positions, ideologies, and parties based on their views regarding the role of government, individual rights, economic policies, and social issues.

The political spectrum is often divided into left-wing, center, and right-wing, with left-wing typically associated with progressive, egalitarian, and government interventionist policies, while right-wing is associated with conservative, traditional, and free-market policies. The center represents moderate or mixed views.

A: No, placement on the political spectrum is subjective and can vary depending on the context, issue, or perspective. Individuals and parties may hold views that span multiple points on the spectrum, making definitive placement challenging.

A: Cultural and regional differences can significantly influence the definition and interpretation of the political spectrum. What is considered left-wing or right-wing in one country may not align with the same labels in another, due to variations in history, values, and political traditions.