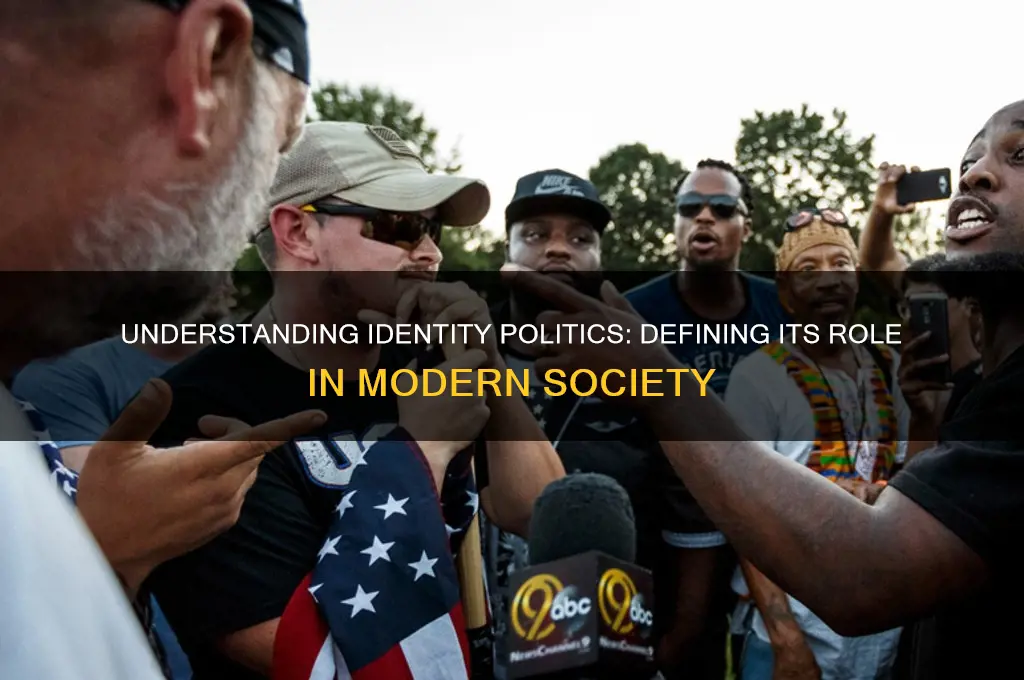

Identity politics refers to the political approaches and movements that focus on the interests and perspectives of specific social groups, often marginalized or underrepresented, based on their shared identities such as race, gender, sexuality, religion, or ethnicity. It emphasizes how these identities shape individuals' experiences, particularly in relation to systemic inequalities and power structures. Defining identity politics involves understanding its role in advocating for recognition, rights, and representation, while also acknowledging debates about its effectiveness and potential to fragment broader political coalitions. At its core, identity politics seeks to address historical and ongoing injustices by centering the voices and needs of those who have been traditionally excluded from mainstream political discourse.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Focus on Group Identity | Emphasizes shared characteristics such as race, gender, sexuality, religion, or ethnicity. |

| Political Mobilization | Uses collective identity to advocate for political, social, or economic change. |

| Intersectionality | Acknowledges overlapping identities and their combined impact on oppression or privilege. |

| Representation | Advocates for greater visibility and inclusion of marginalized groups in politics, media, and institutions. |

| Opposition to Dominant Norms | Challenges societal norms, power structures, and systems that perpetuate inequality. |

| Cultural Affirmation | Celebrates and preserves the cultural heritage and traditions of specific identity groups. |

| Policy Advocacy | Pushes for policies that address the specific needs and rights of identity groups. |

| Grassroots Organizing | Often driven by community-based movements and activism rather than top-down approaches. |

| Critique of Universalism | Argues that "one-size-fits-all" policies fail to address unique experiences of marginalized groups. |

| Global and Local Perspectives | Operates at both local and global levels, addressing both national and transnational issues. |

| Controversy and Debate | Sparks debates about its effectiveness, potential divisiveness, and impact on broader political unity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Roots: Tracing origins in civil rights, feminism, and anti-colonial movements shaping identity-based activism

- Key Concepts: Intersectionality, representation, and power dynamics as core frameworks in identity politics

- Criticisms: Accusations of divisiveness, essentialism, and undermining universal solidarity in political discourse

- Global Perspectives: How identity politics manifests differently across cultures, regions, and political systems

- Practical Applications: Role in policy-making, social movements, and fostering marginalized communities' empowerment

Historical Roots: Tracing origins in civil rights, feminism, and anti-colonial movements shaping identity-based activism

The concept of identity politics, often debated in contemporary discourse, finds its roots in the fertile soil of historical struggles for equality and recognition. To understand its origins, one must trace the threads of civil rights, feminism, and anti-colonial movements, which collectively wove the fabric of identity-based activism. These movements, though distinct in their contexts, shared a common goal: to challenge dominant power structures and assert the rights of marginalized groups.

Consider the civil rights movement in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. African Americans, systematically oppressed under Jim Crow laws, mobilized to demand racial equality. Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and organizations such as the NAACP framed their struggle not just as a fight against legal discrimination but as a reclamation of Black identity and dignity. This movement laid the groundwork for understanding politics through the lens of race, demonstrating that collective identity could be a powerful tool for social change. For instance, the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956) was not merely about bus seating but about challenging the broader systemic dehumanization of Black Americans.

Simultaneously, the feminist movement emerged as a force demanding gender equality. Second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s went beyond suffrage, addressing issues like reproductive rights, workplace discrimination, and domestic violence. Activists like bell hooks and Audre Lorde argued that feminism must intersect with race, class, and sexuality to be truly inclusive. Their work highlighted the importance of recognizing multiple, overlapping identities, a principle that became central to identity politics. For practical application, feminist consciousness-raising groups of the era used personal narratives to politicize private struggles, showing how individual experiences could inform collective action.

Anti-colonial movements in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean further enriched the concept of identity politics by emphasizing the role of culture, language, and history in resisting oppression. Leaders like Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire articulated how colonialism stripped colonized peoples of their identities, necessitating a political movement rooted in cultural reclamation. For example, the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962) was not just a fight for political sovereignty but also a struggle to reclaim Arab and Berber identities suppressed under French rule. This global perspective underscored the universality of identity-based resistance.

These movements collectively taught that identity is not a static category but a dynamic force shaped by historical, social, and political contexts. They demonstrated that activism rooted in identity could challenge systemic inequalities and foster solidarity among marginalized groups. However, they also revealed tensions, such as the risk of essentializing identities or excluding those who do not fit neatly into defined categories. For instance, the Black feminist critique of mainstream feminism for ignoring race highlighted the need for intersectionality, a concept now central to identity politics.

In tracing these historical roots, one takeaway is clear: identity politics is not a modern invention but a legacy of centuries-old struggles for recognition and justice. It is a reminder that identities are both personal and political, shaped by power structures but also capable of reshaping them. To engage with identity politics today, one must acknowledge this history, learn from its successes and failures, and apply its lessons to contemporary challenges. For example, modern activists can emulate the strategic use of storytelling, as seen in the civil rights movement, or the intersectional approach of feminist thinkers, to build more inclusive movements.

Politics Shaping Society: Governance, Policies, and Community Progress Explained

You may want to see also

Key Concepts: Intersectionality, representation, and power dynamics as core frameworks in identity politics

Identity politics is inherently multidimensional, and three frameworks—intersectionality, representation, and power dynamics—are indispensable for understanding its complexity. Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, reveals how overlapping identities (race, gender, class, etc.) create unique experiences of discrimination. For instance, a Black woman faces distinct challenges compared to a white woman or a Black man, as her oppression is compounded by both racism and sexism. This framework demands analysis beyond single-axis lenses, urging us to address systemic inequalities holistically. Without intersectionality, identity politics risks oversimplifying lived realities, perpetuating marginalization within marginalized groups.

Representation serves as both a mirror and a lever in identity politics. Seeing oneself reflected in media, politics, or leadership validates one’s existence and fosters belonging. However, tokenistic representation—a single figurehead in a sea of homogeneity—falls short. Effective representation requires diversity in numbers, roles, and narratives. For example, the rise of Indigenous filmmakers like Taika Waititi challenges colonial stereotypes by reclaiming cultural stories. Yet, representation alone is insufficient; it must be paired with structural change to dismantle barriers to access and opportunity.

Power dynamics underpin every facet of identity politics, dictating who is heard, who is silenced, and who benefits from the status quo. These dynamics are not static but shift across contexts—a woman may hold power in a feminist collective yet be marginalized in a corporate boardroom. Analyzing power involves tracing historical roots of oppression, such as how redlining policies in the U.S. entrenched racial wealth gaps. To challenge these dynamics, strategies like coalition-building and redistributive policies are essential, ensuring that identity politics moves beyond recognition to tangible equity.

In practice, these frameworks are interdependent. Intersectionality exposes the need for diverse representation, which in turn disrupts power imbalances. For instance, the #MeToo movement gained momentum by centering stories of marginalized women, whose voices had long been excluded. Yet, without addressing power—whether through legal reforms or workplace policies—such movements risk remaining symbolic. Together, intersectionality, representation, and power dynamics provide a roadmap for identity politics that is both nuanced and actionable, capable of confronting systemic injustices at their roots.

Nicaragua's Political Stability: Current Realities and Future Prospects Explored

You may want to see also

Criticisms: Accusations of divisiveness, essentialism, and undermining universal solidarity in political discourse

Identity politics, while often celebrated for centering marginalized voices, faces sharp criticism for its perceived divisiveness. Critics argue that by fragmenting political discourse into distinct identity groups, it fosters competition for resources and recognition rather than fostering unity. For instance, debates over affirmative action often pit racial and gender groups against one another, with each advocating for their specific needs. This dynamic, critics claim, can exacerbate social divisions, turning politics into a zero-sum game where one group’s gain is perceived as another’s loss. The result? A fractured public sphere where common ground becomes increasingly elusive.

Another critique targets identity politics for its tendency toward essentialism—the reduction of individuals to fixed, immutable traits based on their identity. This approach risks oversimplifying complex human experiences and reinforcing stereotypes. For example, treating "women" or "Black people" as monolithic entities ignores internal diversity and perpetuates rigid categories. Essentialism can also lead to exclusionary practices, as seen in debates over who qualifies as a "true" representative of a given identity. Such rigidity undermines the fluidity of identity and stifles nuanced political dialogue.

Perhaps the most damning accusation is that identity politics undermines universal solidarity, a cornerstone of progressive movements. By prioritizing specific identity-based grievances, critics argue, it distracts from broader systemic issues that affect all marginalized groups. For instance, focusing solely on racial disparities in policing might overshadow economic inequalities that impact diverse communities. This narrow focus, detractors claim, weakens the collective power needed to challenge overarching structures of oppression. Without a unifying framework, the risk is that identity politics becomes a tool for division rather than liberation.

To navigate these criticisms, proponents of identity politics must strike a delicate balance. Acknowledge the validity of specific struggles while actively seeking intersections with other movements. Avoid essentialist traps by emphasizing the diversity within identity groups and the fluidity of individual experiences. Finally, frame identity-based demands within a broader vision of universal justice, ensuring that the fight for equality remains inclusive and transformative. Only then can identity politics fulfill its promise without succumbing to its pitfalls.

Is the CDC Politically Motivated? Uncovering Facts and Biases

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global Perspectives: How identity politics manifests differently across cultures, regions, and political systems

Identity politics, though often framed as a Western phenomenon, takes on distinct forms across the globe, shaped by local histories, cultural norms, and political structures. In India, for instance, caste identity remains a central axis of political mobilization, with Dalit ("Untouchable") communities leveraging political parties like the Bahujan Samaj Party to challenge centuries-old hierarchies. Here, identity politics isn’t merely about representation—it’s a tool for structural transformation, seeking to dismantle systemic oppression codified in religious texts and social practices. This contrasts sharply with the United States, where identity politics often revolves around race, gender, and sexuality within a liberal democratic framework, focusing on inclusion within existing institutions rather than their overhaul.

In sub-Saharan Africa, ethnic identity frequently dominates political landscapes, but its expression varies dramatically. In Kenya, tribal affiliations like Kikuyu or Luo often determine electoral outcomes, yet these identities are fluid, intersecting with class and regional interests. Conversely, Rwanda’s post-genocide government has actively suppressed ethnic identities in public discourse, promoting a unified "Rwandan" identity to prevent further conflict. This illustrates how identity politics can be both a source of division and a strategy for unity, depending on the state’s role in its construction.

Authoritarian regimes offer another lens. In China, the state co-opts identity politics to consolidate power, promoting Han Chinese nationalism while suppressing Uyghur, Tibetan, and Hong Kong identities through policies like re-education camps and the National Security Law. Here, identity isn’t a tool for liberation but a battleground for control, with the state dictating which identities are permissible and which are threats. This contrasts with the Middle East, where religious identity—particularly Sunni-Shia divisions—is often weaponized by external powers to destabilize regions, as seen in the proxy conflicts of Syria and Yemen.

Indigenous movements in Latin America provide a counterpoint, blending identity politics with anti-colonial struggles. In Bolivia, the election of Evo Morales, the country’s first Indigenous president, symbolized a reclamation of Indigenous identity within a plurinational state framework. Here, identity politics isn’t just about recognition—it’s about reshaping governance to reflect Indigenous worldviews, such as the legal concept of *Pachamama* (Mother Earth) rights. This model challenges Western notions of individualism, centering collective identity and ecological stewardship.

To navigate these global variations, consider three practical takeaways: First, avoid universalizing Western frameworks of identity politics; what constitutes "progress" in one context may be irrelevant or counterproductive elsewhere. Second, analyze the role of the state—whether it amplifies, suppresses, or reshapes identities—to understand the stakes of identity-based movements. Third, recognize that identity politics is never static; it evolves in response to historical injustices, economic shifts, and global influences. By adopting a context-specific lens, we can better appreciate how identity politics serves as both a mirror and a hammer, reflecting societal fractures while shaping the possibilities for change.

Is Country Independence Truly Political? Exploring Sovereignty and Global Dynamics

You may want to see also

Practical Applications: Role in policy-making, social movements, and fostering marginalized communities' empowerment

Identity politics, at its core, centers on how aspects of identity—such as race, gender, sexuality, and class—shape political and social experiences. In practical terms, this framework becomes a tool for marginalized communities to assert their needs, challenge systemic inequalities, and drive policy changes that reflect their realities. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement leverages identity politics to spotlight racial injustice, pushing for police reform and anti-discrimination laws. This example underscores how identity-based advocacy can translate into tangible policy shifts, demonstrating the framework’s utility in reshaping institutional structures.

In policy-making, identity politics serves as both a lens and a lever. Policymakers can use it to identify disparities in outcomes for specific groups, such as higher maternal mortality rates among Black women or lower wages for Latina workers. By disaggregating data by race, gender, and other identity markers, governments can craft targeted interventions. For example, the implementation of the Violence Against Women Act in the U.S. was driven by feminist identity politics, addressing gender-based violence through funding for shelters, legal aid, and prevention programs. However, caution is necessary: policies must avoid tokenism or stereotyping, ensuring they empower rather than pigeonhole communities.

Social movements thrive on identity politics as a mobilizing force. The LGBTQ+ rights movement, for instance, has used shared identities to build solidarity, from the Stonewall riots to the fight for marriage equality. These movements often employ storytelling and visibility campaigns to humanize their struggles, making abstract issues like discrimination or exclusion relatable to broader audiences. A practical tip for activists: frame demands in ways that resonate with both the affected community and allies, such as emphasizing shared values like equality or justice. This dual appeal amplifies impact, turning identity-based movements into catalysts for societal change.

For marginalized communities, identity politics fosters empowerment by validating lived experiences and creating spaces for collective action. Indigenous groups, for example, have used identity-based organizing to reclaim land rights and preserve cultural practices. In practice, this might involve community-led initiatives like language revitalization programs or legal battles against corporate encroachment. A key takeaway: empowerment requires not just external policy changes but internal capacity-building, such as leadership training or resource pooling within the community. This dual approach ensures sustainability and self-determination.

Finally, while identity politics is a powerful tool, its application requires nuance. Overemphasis on single-axis identities (e.g., race alone) can obscure intersecting oppressions, such as how Black women face unique challenges at the crossroads of racism and sexism. Policymakers and activists must adopt an intersectional approach, addressing multiple layers of marginalization simultaneously. For instance, affordable housing policies should consider how race, gender, and disability status compound access barriers. By doing so, identity politics becomes not just a means of representation but a strategy for holistic transformation.

Launching Your Political Journey: A Beginner's Guide to Public Service

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identity politics refers to political positions based on the interests and perspectives of social groups with which people identify, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, or disability. It emphasizes how these identities shape individuals' experiences and advocates for their representation and rights.

Identity politics is controversial because critics argue it can lead to divisiveness, prioritizing group interests over broader societal unity, or overshadowing other important political issues. Supporters, however, see it as essential for addressing systemic inequalities and amplifying marginalized voices.

Identity politics influences policy-making by advocating for laws and initiatives that address the specific needs and challenges of marginalized groups. Examples include affirmative action, LGBTQ+ rights, and racial justice reforms, which aim to create more equitable systems.

Yes, identity politics can coexist with broader political movements by addressing intersectional issues that affect multiple groups. For instance, movements for economic justice often incorporate identity-based perspectives to ensure policies benefit all communities equitably.