The US Constitution's Commerce Clause, found in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3, gives Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with the Indian tribes. This clause has been interpreted and re-interpreted over the years, sparking extensive debate and Supreme Court rulings. The Commerce Clause has been used to justify congressional authority over state regulatory authority, impacting the separation of powers between federal and state governments. The interpretation and application of the Commerce Clause have evolved, affecting public health, environmental protection, and societal issues. The creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887 marked a turning point in federal policy, demonstrating Congress's ability to address national problems through the expansive use of the Commerce Clause.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The Commerce Clause

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time, with the Supreme Court playing a pivotal role in shaping its meaning. In the early 19th century, the Court moved towards a broader interpretation, recognising the need for a more robust federal government in a maturing nation. This culminated in the 1824 Gibbons v. Ogden case, where the Court affirmed that intrastate activity could be regulated under the Commerce Clause if it was part of a broader interstate commercial scheme.

However, in the decades leading up to the New Deal, the Supreme Court narrowed its interpretation, striking down several laws aimed at safeguarding public health and protecting workers' rights, such as in the A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S. case. This era, known as the Lochner era, lasted from 1905 to 1937 and was characterised by a more conservative approach to interpreting the Commerce Clause.

A significant shift occurred in 1937 with the NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp case, marking the beginning of an extremely expansive interpretation of the Commerce Clause by the Supreme Court. This era witnessed no federal laws found to violate Congress's commerce power until 1995. Cases such as NLRB v. Jones, United States v. Darby, and Wickard v. Filburn exemplified the Court's willingness to interpret the Commerce Clause broadly, recognising Congress's authority to regulate activities with a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce.

The Cherokee Constitution: A US Influence

You may want to see also

The Dormant Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause, outlined in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the authority to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among states, and with Native American tribes. This clause has been interpreted broadly, allowing the federal government to address national challenges and regulate the economy.

The Supreme Court has identified two key principles in its modern interpretation of the Dormant Commerce Clause. Firstly, states may not discriminate against interstate commerce. Secondly, states may not implement laws that appear neutral but unduly burden interstate commerce. For example, in West Lynn Creamery Inc. v. Healy, the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts state tax on milk products as it impeded interstate commerce by discriminating against non-Massachusetts citizens and businesses.

The interpretation and application of the Dormant Commerce Clause continue to evolve through Supreme Court rulings, shaping the boundaries between federal and state power in the United States.

Lincoln's View: Slavery and the Constitution

You may want to see also

Congress's legislative powers

The US Constitution's Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3, grants Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". This clause has been a fundamental part of American law, shaping the boundaries between federal power and state power. It allows the federal legislature to regulate the economy and protect the interests of the American people.

Congress has often used the Commerce Clause to justify exercising legislative power over the activities of states and their citizens, leading to significant and ongoing controversy regarding the balance of power between the federal government and the states. The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time, with the Supreme Court playing a crucial role in defining its scope. Initially, the Court interpreted commerce narrowly, including only trade and navigation. However, in cases such as NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp (1937), the Court began to adopt a broader interpretation, asserting that any activity with a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce fell within the scope of the clause.

The Commerce Clause also affects state governments through the Dormant Commerce Clause, which prohibits states from passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce. For example, in West Lynn Creamery Inc. v. Healy, the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts state tax on milk products as it impeded interstate commerce by discriminating against non-Massachusetts citizens and businesses.

In addition to the Commerce Clause, Congress derives its legislative powers from various other provisions in the Constitution. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution outlines several specific powers of Congress, including the power to establish uniform rules of naturalization, coin money, provide for punishments for counterfeiting, promote scientific progress, and declare war, among others.

The legislative powers of Congress during the 1800s were shaped by the formative years of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate first convened in 1789 behind closed doors, but eventually opened its doors to the public due to pressure from the people, the press, and state legislatures. The House of Representatives moved to Washington, D.C. in 1800, and influential figures such as Henry Clay played a significant role in enhancing the Speaker's power during this period.

Homeschooling: High School Diploma Equivalent?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Supreme Court's role

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among states, and with the Indian tribes. The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been contentious, with debate surrounding the scope of powers it grants Congress. This interpretation holds significant weight in the separation of powers between federal and state governments.

However, in the decades preceding the New Deal, the Supreme Court narrowed its interpretation, striking down several laws aimed at protecting public health. For example, in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. U.S., the Court overturned a federal law prohibiting the sale of unhealthy chickens, arguing it interfered with labour conditions. Similarly, in Federal Baseball Club v. National League, the Court excluded live entertainment from the definition of commerce.

In the 20th century, the Supreme Court continued to shape the interpretation of the Commerce Clause. In 1905's Swift and Company v. United States, the Court affirmed Congress's authority over local commerce that could become part of interstate commerce. From 1937 onwards, the Court recognised broader grounds for using the Commerce Clause to regulate state activity, holding that any activity with a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce fell within its scope.

The Supreme Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause has also impacted modern societal issues, such as healthcare reform. While the Court upheld the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate, it did not do so under the Commerce Clause, instead relying on Congress's taxing power. The Court's role in interpreting the Commerce Clause remains essential in maintaining the constitutional equilibrium and safeguarding democracy through checks and balances.

Constitution's Journey: From Idea to Law

You may want to see also

Commerce and federalism

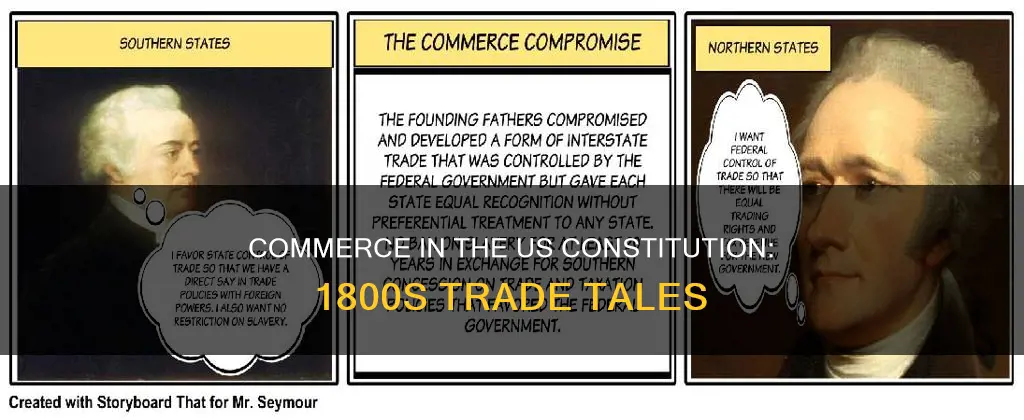

During the 1800s, the US Constitution's handling of commerce evolved. In the early 19th century, commerce between states was largely conducted along the Atlantic seaboard and inland waterways. The Constitution established the promotion of general welfare as one of the key goals of the government, with President William Taft signing legislation creating the Department of Commerce in 1913. The Constitution also made provisions for a Secretary of Commerce and Finance, responsible for promoting the commercial interests of the United States.

In the mid-1800s, the country experienced economic depression, and the National Association of Manufacturers advocated for the formation of a Department of Commerce and Industry. Instead, Congress established a US Industrial Commission to address economic and social issues, including the impact of corporate trusts. By the end of the century, the national economy had become highly integrated, making almost all commerce interstate and international.

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 marked a significant shift in federal policy. Before this Act, Congress had applied the Commerce Clause only to remove barriers that states imposed on interstate trade. The Act demonstrated that Congress could use the Commerce Clause more expansively to address national issues involving commerce across state lines, such as regulating railroad rates. The Supreme Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause has played a crucial role in shaping constitutional law and the boundaries between federal and state powers. The Court has ruled on the scope of congressional authority under the Commerce Clause, with cases such as United States v. Lopez (1995) and Gonzales v. Raich shaping the understanding of this clause.

In conclusion, during the 1800s, the US Constitution's approach to commerce evolved from managing interstate trade barriers to addressing national issues through the expansive interpretation of the Commerce Clause. The federal government's power to regulate commerce and the complex interplay between federal and state jurisdictions remain central aspects of American federalism.

Constitutional Provisions: Different Analysis, Same Weight as Statutes?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Commerce Clause is a section of the US Constitution that gives Congress the power to manage business activities that cross state borders and has grown to include a wide range of economic dealings. It is found in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution.

The Commerce Clause was used to address issues of interstate commerce, such as the regulation of railroad rates. For example, in 1887, the Interstate Commerce Act was passed, which applied the Commerce Clause to regulating railroad rates, ensuring that small businesses and farmers were not charged higher rates than larger corporations.

The US Constitution, through the Commerce Clause, gave Congress the power to regulate commerce between states. This included removing barriers that states tried to impose on interstate trade. The Constitution also allowed for the creation of committees and departments to oversee commerce and related matters, such as the Committee of Commerce and Manufactures in 1795 and the Department of Agriculture in 1889.

![The American Fur Trade of the Far West [Two Volumes in One]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71lTyhKbPRL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![A History of Violence (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71lqpbUFtWL._AC_UY218_.jpg)