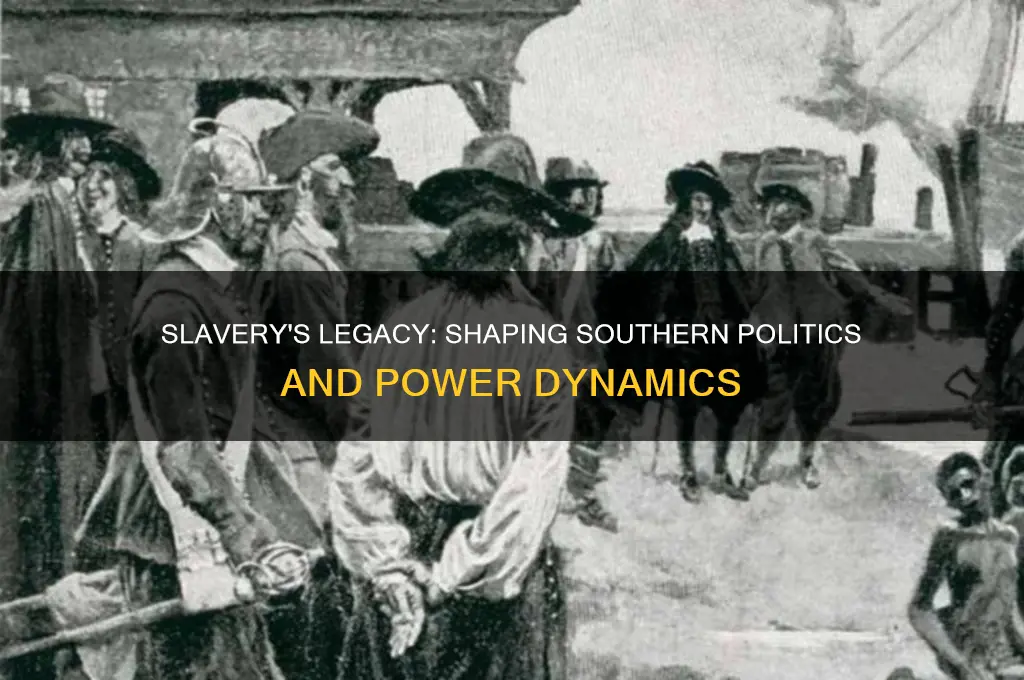

Slavery played a pivotal role in shaping Southern politics during the antebellum era, serving as the economic and social foundation upon which the region's political power was built. The institution of slavery not only fueled the South's agrarian economy but also entrenched a hierarchical social order that privileged white landowners, who dominated political offices and crafted policies to protect their interests. Southern politicians leveraged slavery to solidify their control over state and federal governments, advocating for states' rights and the expansion of slavery into new territories to maintain their economic and political dominance. This system of exploitation also fostered a culture of racial supremacy, which became a cornerstone of Southern political ideology, influencing legislation, electoral strategies, and the region's staunch resistance to abolitionism. Thus, slavery was not merely an economic institution but a political tool that underpinned the South's power structure and its enduring legacy in American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Economic Power | Slavery provided a labor force that drove the Southern economy, particularly in agriculture (cotton, tobacco, sugar). This economic dominance translated into political influence, as wealthier states held more power in Congress and electoral votes. |

| Political Representation | The Three-Fifths Compromise allowed Southern states to count enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation in Congress and the Electoral College, inflating their political power. |

| Social Hierarchy | Slavery reinforced a racial hierarchy that justified white supremacy. This ideology was used to unite white Southerners across class lines, solidifying political support for pro-slavery policies. |

| Control of Labor | Enslaved labor was cheaper and more controllable than free labor, allowing Southern elites to maintain economic and political control. This control extended to suppressing dissent and maintaining the status quo. |

| Expansionism | Southern politicians pushed for the expansion of slavery into new territories to maintain their economic and political dominance, leading to conflicts like the Mexican-American War and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. |

| Legislative Influence | Southern politicians dominated key committees in Congress, such as the Senate Committee on Territories, to protect and expand slavery. They also used filibusters to block anti-slavery legislation. |

| Cultural and Ideological Unity | Slavery was central to Southern identity and culture, fostering a unified political front against perceived Northern threats to their way of life. |

| Military and Strategic Advantage | The labor provided by enslaved people allowed Southern states to focus resources on military preparedness, which was crucial during the Civil War. |

| Suppression of Opposition | Slavery enabled the suppression of political opposition, both among enslaved people and free Black individuals, ensuring that pro-slavery voices dominated Southern politics. |

| Global Economic Influence | The Southern economy, fueled by slavery, played a significant role in global trade, particularly in cotton, which gave Southern politicians leverage in international relations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Economic Power of Slave Labor

Slave labor was the backbone of the Southern economy, and its economic power shaped the political landscape of the region in profound ways. By the mid-19th century, the Southern United States had become a global powerhouse in cotton production, accounting for approximately 75% of the world’s cotton supply. This dominance was built entirely on the exploitation of enslaved labor. Cotton plantations, which required intensive manual labor, thrived because enslaved people were forced to work without wages, benefits, or rights. The sheer scale of this unpaid labor force generated immense wealth for plantation owners, who reinvested their profits into political influence, land acquisition, and further expansion of slavery. This economic system not only enriched a small elite but also created a dependency that Southern politicians fiercely defended as essential to their way of life.

Consider the numbers: in 1860, the market value of enslaved people in the United States exceeded the combined value of all banks, railroads, and factories in the nation. A single enslaved person could be sold for upwards of $1,000 (equivalent to over $30,000 today), making them one of the most valuable assets in the South. This economic stake in slavery translated directly into political power. Southern politicians, many of whom were plantation owners themselves, used their wealth to dominate state legislatures and congressional delegations. They advocated for policies that protected and expanded slavery, such as the Fugitive Slave Act and the expansion of slavery into new territories. The economic power of slave labor thus became a tool to entrench political control and resist any threats to the institution of slavery.

To understand the depth of this influence, examine the role of slavery in shaping Southern infrastructure and trade. Entire industries, from textile mills to shipping ports, were built to support the cotton economy. Cities like New Orleans and Charleston flourished as hubs for exporting cotton to Europe, while railroads were constructed primarily to transport raw materials and enslaved people to plantations. This economic interdependence meant that any challenge to slavery was framed as an attack on the Southern economy itself. Politicians leveraged this fear, arguing that abolition would lead to economic collapse and social upheaval. By tying the region’s prosperity to the continued exploitation of enslaved labor, they ensured that slavery remained a non-negotiable pillar of Southern politics.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between the South’s reliance on slave labor and the North’s wage-based economy. While the North industrialized and diversified its economy, the South doubled down on agriculture, particularly cotton. This specialization made the South economically vulnerable but politically unified. Southern leaders used this vulnerability to their advantage, portraying slavery as the linchpin of their society. They rallied voters with warnings of economic ruin and racial hierarchy, ensuring widespread support for pro-slavery policies. The economic power of slave labor, therefore, was not just a source of wealth but a means of political mobilization and ideological cohesion.

In practical terms, the economic power of slave labor allowed Southern politicians to dominate national debates and shape federal policies. For instance, the three-fifths compromise in the Constitution gave Southern states disproportionate representation in Congress based on their enslaved populations. This political leverage enabled them to block anti-slavery legislation and even influence presidential elections. The economic might of slavery, in other words, was converted into political capital, ensuring that the South’s interests were prioritized at the highest levels of government. This dynamic underscores how deeply intertwined economic exploitation and political power were in the antebellum South.

Is Identity Politics Racist? Exploring the Intersection of Race and Ideology

You may want to see also

Political Influence of Slaveholders

Slaveholders in the American South wielded disproportionate political power through a system that counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation in Congress. This compromise, enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, inflated the South's congressional delegation and Electoral College votes, giving slaveholders outsized influence in national policy. For example, in 1850, the South held 84 seats in the House of Representatives, despite having a smaller free population than the North. This mathematical advantage allowed Southern politicians to block anti-slavery legislation and shape federal policies in their favor, such as the Fugitive Slave Act, which compelled Northern states to return escaped slaves.

The economic power derived from slavery further cemented the political dominance of slaveholders. Cotton, produced primarily through enslaved labor, became the South's economic backbone, accounting for over half of the nation's exports by the 1850s. This wealth translated into political clout, as wealthy planters funded campaigns, controlled state legislatures, and dominated Southern delegations in Congress. Figures like John C. Calhoun exemplified this influence, using their positions to defend slavery as a "positive good" and to argue for states' rights to protect the institution. The intertwining of economic and political power ensured that slavery remained a non-negotiable pillar of Southern politics.

Slaveholders also manipulated political institutions at the state level to maintain their grip on power. In states like South Carolina and Mississippi, property qualifications for voting and office-holding ensured that only the wealthiest planters could participate in governance. Additionally, the intimidation and exclusion of non-slaveholding whites through social and economic pressure kept dissent in check. This internal political control allowed slaveholders to present a united front against Northern abolitionists and federal intervention, framing the defense of slavery as a matter of regional survival and honor.

The legacy of slaveholders' political influence extended beyond the Civil War, shaping the South's post-Reconstruction era. The disenfranchisement of Black voters through Jim Crow laws and the rise of the "Solid South" in Democratic politics were direct continuations of the pre-war power structure. Former slaveholding elites repurposed their political machinery to maintain white supremacy, ensuring that the economic and social hierarchies built on slavery persisted in new forms. Understanding this continuity is crucial for addressing the systemic inequalities that still affect the South today.

Bridging Divides: Effective Strategies to Resolve Political Conflict Peacefully

You may want to see also

Three-Fifths Compromise Impact

The Three-Fifths Compromise, a pivotal agreement during the 1787 Constitutional Convention, had a profound and lasting impact on the political landscape of the American South. This compromise, which counted three-fifths of the enslaved population for representation in Congress and taxation purposes, effectively bolstered the political power of the southern states. By inflating their population numbers, the South gained more seats in the House of Representatives and a greater say in presidential elections through the Electoral College. This disproportionate representation allowed southern politicians to advocate for policies that protected and expanded the institution of slavery, ensuring its centrality to the southern economy and way of life.

Consider the mathematical advantage this compromise provided. If a southern state had 100,000 enslaved individuals, 60,000 of them (three-fifths) were counted for representation. This meant that southern states, despite having a smaller free population, could rival or surpass northern states in congressional influence. For instance, in the First U.S. Congress (1789–1791), southern states held 33 out of 65 seats in the House of Representatives, a majority that allowed them to shape federal legislation in favor of slavery. This political leverage was instrumental in passing laws like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which further entrenched slavery across the nation.

The compromise’s impact extended beyond immediate political gains; it institutionalized the southern perspective in national governance. Southern politicians used their inflated representation to block or weaken anti-slavery measures, such as the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, which was delayed until 1808. Additionally, the compromise’s legacy persisted even after the Civil War, influencing the Reconstruction era and the Jim Crow laws that followed. The political power it granted the South helped maintain a pro-slavery ideology that shaped American politics for nearly a century.

To understand the practical implications, examine how this compromise affected specific elections. In the 1800 presidential race, Thomas Jefferson’s victory over Aaron Burr was secured in part due to the additional electoral votes from southern states, where enslaved populations were counted under the Three-Fifths Compromise. This example illustrates how the compromise not only skewed representation but also directly influenced the outcome of national leadership, ensuring that pro-slavery interests remained at the forefront of American politics.

In conclusion, the Three-Fifths Compromise was a cornerstone of southern political dominance, providing a structural advantage that perpetuated slavery and its associated ideologies. Its impact was both immediate and long-lasting, shaping legislation, elections, and the very fabric of American governance. By understanding this compromise, we gain insight into how systemic inequalities were embedded in the nation’s founding documents and how they continue to influence political dynamics today.

Memorial Day: Honoring Sacrifice or Political Divide?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.29 $14.95

$50.15 $44.99

Cotton Economy and Politics

The cotton economy of the American South was inextricably linked to the institution of slavery, and this relationship profoundly shaped the region's political landscape. Cotton, often referred to as 'white gold', became the South's dominant crop in the early 19th century, transforming the region's economy and solidifying the power of the planter elite. This economic shift had far-reaching political consequences, as the wealth generated from cotton production became a driving force in Southern politics, influencing policy, legislation, and the very structure of society.

The Rise of King Cotton

Imagine a single crop so valuable that it could dictate the course of a nation's history. Cotton, with its insatiable global demand, became the South's economic backbone. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 revolutionized the industry, making cotton production highly profitable. As a result, the South experienced a rapid expansion of cotton plantations, and the institution of slavery grew in tandem. Slaves were the primary labor force, and their exploitation was central to the South's economic success. The more cotton a plantation produced, the more wealth and influence its owner garnered. This created a powerful incentive to expand slavery and protect it at all costs.

Political Power and the Planter Elite

The cotton economy gave rise to a powerful class of planters who dominated Southern politics. These elite planters held significant political office, shaped legislation, and controlled the region's economic policies. Their influence was such that they could dictate terms to other Southerners, including small farmers and non-slaveholders. The political agenda of the South became increasingly focused on protecting and expanding slavery to ensure the continued prosperity of the cotton kingdom. This included advocating for the annexation of new territories to expand cotton production and resisting any attempts at federal regulation or abolition.

A Comparative Perspective: Cotton vs. Other Crops

To understand the unique impact of cotton, consider the contrast with other agricultural economies. In the North, for instance, a diverse range of crops and industries flourished, leading to a more distributed power structure. In contrast, the South's economy was heavily concentrated in cotton, making it vulnerable to market fluctuations and creating a strong incentive to maintain the status quo. The political system in the South became a tool to safeguard the interests of the planter class, often at the expense of other social and economic groups. This single-crop dominance had long-term consequences, shaping the South's resistance to change and its eventual secession during the Civil War.

The Legacy and Takeaway

The cotton economy's influence on Southern politics cannot be overstated. It created a powerful alliance between economic interests and political power, with slavery as the linchpin. This dynamic had far-reaching effects, including the entrenchment of racial hierarchies and the suppression of alternative economic models. Understanding this relationship is crucial for comprehending the South's historical trajectory and the challenges it faced in the post-Civil War era. By examining the cotton economy, we uncover a critical aspect of how slavery shaped not just the South's politics but also its social and economic structures, leaving a legacy that continues to influence the region's identity.

Is Nigeria Politically Stable? Analyzing Governance, Challenges, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Slave States' Legislative Dominance

The Three-Fifths Compromise, a constitutional agreement reached in 1787, granted slave states disproportionate political power by counting each enslaved person as three-fifths of a person for representation purposes. This compromise effectively inflated the population of slave states, granting them additional seats in the House of Representatives and, consequently, more electoral votes. For instance, in 1790, Virginia's enslaved population of approximately 292,000 resulted in the state gaining 12 additional congressional seats, a significant advantage over free states with comparable free populations.

This legislative dominance had far-reaching consequences, shaping policy and perpetuating the institution of slavery. Slave states consistently wielded their inflated representation to block anti-slavery legislation, such as the Wilmot Proviso (1846) and the proposed abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. Moreover, they used their power to admit new slave states, maintaining a delicate balance in the Senate and ensuring their continued influence. The admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1821, for example, was a direct result of slave states' legislative dominance, as it preserved the equal representation of slave and free states in the Senate.

To understand the extent of this dominance, consider the following: between 1789 and 1861, slave states held the presidency for 50 out of 72 years, with only two presidents (John Adams and Millard Fillmore) hailing from free states during this period. This disproportionate representation allowed slave states to shape national policies, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which compelled citizens to assist in the capture and return of escaped slaves, further entrenching slavery.

A comparative analysis of voting patterns reveals that slave states consistently voted as a bloc, leveraging their collective power to advance pro-slavery agendas. In contrast, free states were often divided on issues such as tariffs and internal improvements, diluting their influence. This unity among slave states was a direct result of their shared economic and political interests, which were inextricably linked to the preservation of slavery.

In practical terms, this legislative dominance meant that policies benefiting the South, such as the expansion of slavery into new territories, were prioritized over those benefiting the North, like infrastructure development. For example, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, was a direct consequence of slave states' power. This act allowed popular sovereignty to determine the status of slavery in new territories, leading to the violent conflict known as "Bleeding Kansas."

The takeaway is clear: slave states' legislative dominance was a powerful tool for maintaining and expanding slavery, shaping national policies, and perpetuating a system of racial hierarchy. By exploiting the Three-Fifths Compromise and strategic admissions of new slave states, the South secured a political advantage that had profound and lasting consequences for American history. Understanding this dynamic is essential for comprehending the complex interplay between slavery, politics, and power in the antebellum United States.

Cultural vs. Political: Unraveling the Distinct Influences Shaping Societies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Slavery bolstered Southern political power through the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for representation in Congress and electoral votes, giving the South disproportionate influence in federal politics.

Slavery reinforced a political ideology centered on states' rights, limited federal government, and white supremacy, as Southern leaders sought to protect the institution of slavery from perceived Northern and federal threats.

Slavery was a unifying issue for Southern politicians, leading to the dominance of the Democratic Party in the region, as it consistently defended slavery and Southern economic interests against the growing antislavery movement in the North.

Yes, slavery allowed the South to maintain a strong presence in national elections through the electoral votes and congressional seats gained via the Three-Fifths Compromise, influencing presidential outcomes and legislative decisions.

Slavery was the primary catalyst for secession, as Southern leaders feared that the election of Abraham Lincoln and the rise of the Republican Party threatened the institution of slavery, prompting them to form the Confederate States of America to protect it.