Australia operates as a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with a political system deeply influenced by its British heritage and adapted to its unique national context. The country’s government is structured around the principles of representative democracy, separation of powers, and the rule of law. At its core, the Australian political system is divided into three levels: federal, state, and local. The federal government, based in Canberra, holds authority over national matters such as defense, foreign policy, and trade, while state and territory governments manage areas like education, health, and public transport. The Parliament of Australia consists of two houses—the House of Representatives and the Senate—with the Prime Minister serving as the head of government. Politics in Australia is dominated by two major parties, the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal-National Coalition, though minor parties and independents play significant roles, particularly in the Senate. Elections are held regularly, and compulsory voting ensures high voter turnout. The interplay between these levels of government, the influence of political parties, and the role of the judiciary in interpreting the Constitution collectively shape how politics functions in Australia, reflecting a dynamic and evolving democratic process.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Federal System: Australia's three-tiered government structure and division of powers

- Electoral System: Preferential voting, compulsory voting, and single transferable vote mechanisms

- Political Parties: Major parties (Labor, Liberal, Nationals) and their ideologies

- Parliament: Roles of House of Representatives, Senate, and legislative processes

- Prime Minister: Powers, responsibilities, and relationship with the Governor-General

Federal System: Australia's three-tiered government structure and division of powers

Australia's federal system is a complex interplay of three tiers of government, each with distinct roles and responsibilities. At the apex sits the Federal Government, wielding powers outlined in the Australian Constitution. This tier handles national matters like defense, foreign affairs, immigration, and trade. Imagine it as the backbone, ensuring unity and consistency across the nation. Below it, the State and Territory Governments form the middle layer, managing areas like education, health, public transport, and law enforcement. Think of them as the limbs, adapting national policies to local needs and realities. Finally, the Local Governments, often overlooked, are the fingers and toes, dealing with hyper-local issues like waste management, parks, and community services. This three-tiered structure ensures both centralized authority and localized responsiveness, a delicate balance that defines Australian governance.

The division of powers in Australia’s federal system is both a strength and a source of tension. The Constitution grants the Federal Government specific powers, while residual powers remain with the states. For instance, the Commonwealth controls taxation, but states manage hospitals. This division often leads to jurisdictional disputes, such as funding battles over schools or roads. A practical example is the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), jointly funded by the Commonwealth and states but administered differently across regions. To navigate this, citizens must understand which tier to approach for specific issues: federal for passports, state for driver’s licenses, and local for building permits. This clarity is crucial for effective civic engagement.

Consider the COVID-19 pandemic as a case study in Australia’s federal dynamics. The Federal Government led on international border closures and vaccine procurement, while State Governments enforced lockdowns and managed health systems. Local Governments played a role in disseminating information and supporting vulnerable communities. This layered response highlighted both the system’s flexibility and its challenges. Coordination between tiers was often strained, with conflicting messages and policies. For instance, while the Commonwealth provided vaccines, states controlled rollout speeds, leading to public confusion. This example underscores the need for clearer communication and collaboration mechanisms within the federal framework.

To make Australia’s federal system work for you, start by identifying the right tier for your concern. Need a Medicare card? That’s federal. Want to report a pothole? Contact your local council. For broader issues like climate change, engage with both federal and state representatives, as policies often require multi-tiered action. Advocacy groups often target specific tiers based on their powers—for instance, lobbying the Commonwealth for national environmental laws or pressuring states for better public housing. Understanding this structure empowers citizens to navigate the system effectively, ensuring their voices are heard at the appropriate level.

In conclusion, Australia’s three-tiered federal system is a dynamic framework designed to balance national unity with local autonomy. While its division of powers can lead to complexities, it also fosters adaptability and responsiveness. By understanding the roles of each tier and their interplay, citizens can better engage with the system, advocate for change, and hold their governments accountable. Whether addressing a local park issue or a national crisis, this knowledge is a powerful tool in Australia’s democratic toolkit.

Is Pam Bondy Exiting Politics? Exploring Her Future Plans

You may want to see also

Electoral System: Preferential voting, compulsory voting, and single transferable vote mechanisms

Australia's electoral system is a complex interplay of mechanisms designed to ensure representation, participation, and fairness. At its core are three distinctive features: preferential voting, compulsory voting, and the single transferable vote (STV). Together, these elements shape how Australians elect their representatives and how their political landscape operates.

Preferential voting, also known as instant-runoff voting, requires voters to rank candidates in order of preference. This system eliminates the "spoiler effect" often seen in first-past-the-post systems, where a third candidate can split the vote and allow a less popular candidate to win. For instance, in a three-candidate race, if no one achieves a majority, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed to the remaining candidates based on second preferences. This process continues until one candidate secures a majority. This method ensures that the winning candidate has broader support, reflecting a more accurate representation of the electorate’s preferences.

Compulsory voting is another cornerstone of Australia’s electoral system, requiring all eligible citizens aged 18 and over to enroll and vote in federal and state elections. Failure to vote can result in fines, typically starting at $20 for a first offense. This policy has consistently maintained high voter turnout, often exceeding 90%. Critics argue it infringes on personal freedom, but proponents highlight its role in fostering civic engagement and ensuring that governments are elected by a truly representative sample of the population. For practical compliance, voters should ensure their enrollment details are up-to-date and familiarize themselves with polling locations or postal voting procedures.

The single transferable vote (STV) mechanism is primarily used in upper house elections, such as the Senate, and some state legislatures. STV allows voters to rank candidates in multi-seat constituencies, with votes redistributed until all positions are filled. This proportional representation system ensures that minority groups gain representation, as candidates need only a quota of votes rather than a majority. For example, in a six-seat electorate, a candidate needs approximately 14.3% of the vote to secure a seat. This method contrasts with preferential voting in single-seat electorates, offering a more nuanced approach to representation in larger bodies.

In practice, these mechanisms interact to create a dynamic electoral system. Preferential voting encourages parties to appeal to a broader electorate, as second and third preferences can be crucial. Compulsory voting ensures that this system operates with high participation rates, reducing the risk of skewed outcomes. STV complements these by providing proportional representation in certain contexts, balancing the majoritarian tendencies of preferential voting. Together, they form a robust framework that prioritizes inclusivity, fairness, and active citizenship in Australian politics.

Jeff Bezos' Political Influence: Power, Philanthropy, and Policy Impact

You may want to see also

Political Parties: Major parties (Labor, Liberal, Nationals) and their ideologies

Australia's political landscape is dominated by three major parties: the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the Liberal Party of Australia, and the National Party of Australia. These parties shape policies, influence public opinion, and determine the country’s direction. Understanding their ideologies is key to grasping how Australian politics operates.

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), often referred to as Labor, is Australia’s oldest political party, founded in the late 19th century. Rooted in the labor movement, Labor’s ideology centers on social democracy, advocating for workers’ rights, progressive taxation, and a strong welfare state. Key policies include universal healthcare (Medicare), investment in public education, and support for trade unions. Labor positions itself as the party of fairness and equality, often appealing to urban and working-class voters. For instance, its commitment to raising the minimum wage and addressing income inequality reflects its core values. However, Labor’s approach to economic management has evolved, balancing traditional left-wing principles with pragmatic fiscal policies to maintain electoral appeal.

In contrast, the Liberal Party of Australia represents the center-right of the political spectrum, despite its name suggesting otherwise. Founded in 1945, the Liberals advocate for free-market capitalism, individual liberty, and limited government intervention. Their policies emphasize lower taxes, deregulation, and private enterprise. Historically, the party has championed strong national defense and close ties with traditional allies like the United States. While often associated with conservative values, the Liberals are not uniformly so; they include both moderate and conservative factions. For example, while some members push for climate action, others prioritize economic growth over environmental regulation. This internal diversity can lead to policy tensions but also broadens their electoral base.

The National Party of Australia, formerly known as the Country Party, focuses on representing rural and regional interests. Its ideology is rooted in agrarianism, advocating for farmers, regional development, and decentralized governance. The Nationals often form a coalition with the Liberal Party, sharing power and policy influence. Key priorities include water security, infrastructure investment in rural areas, and support for primary industries. While their voter base is smaller compared to Labor and the Liberals, the Nationals’ influence is disproportionate due to their coalition arrangement. For instance, their push for coal mining in regional areas has shaped national energy policy, highlighting their ability to amplify rural concerns on the national stage.

Comparing these parties reveals distinct ideological divides but also areas of overlap. Labor and the Liberals, for instance, both support a strong economy but differ on how to achieve it—Labor through government intervention and the Liberals through free-market principles. The Nationals, meanwhile, carve out a niche by focusing on issues often overlooked by their urban-centric counterparts. These differences are not just theoretical; they translate into tangible policies affecting healthcare, education, the environment, and the economy. For voters, understanding these ideologies is crucial for making informed decisions, as each party’s vision for Australia varies significantly.

In practice, the interplay between these parties drives Australian politics. Labor and the Coalition (Liberals and Nationals) dominate federal elections, with minor parties and independents playing a growing role in shaping outcomes. While ideological purity is rare in practice, each party’s core principles guide their actions, making their ideologies a practical tool for predicting policy directions. For anyone navigating Australian politics, recognizing these distinctions is essential—whether you’re a voter, policymaker, or observer.

Is Nazi Ideology Political? Unraveling the Complexities of Extremism

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Parliament: Roles of House of Representatives, Senate, and legislative processes

Australia's federal parliament is a bicameral system, meaning it consists of two houses: the House of Representatives and the Senate. Each plays a distinct role in the legislative process, ensuring a balance of power and representation.

The House of Representatives: The People's Voice

Imagine a room buzzing with debate, where 151 elected members, each representing a specific geographic area (electorate), passionately advocate for their constituents. This is the House of Representatives, often referred to as the "people's house." Its primary function is to initiate and pass legislation, reflecting the will of the Australian people. Members are elected for a maximum term of three years, ensuring regular accountability to their electorates. To pass a bill, a simple majority (76 votes) is required, making the House a powerful driver of government policy. However, its power is checked by the Senate, preventing hasty or partisan legislation.

Key takeaway: The House of Representatives is the engine of legislative change, directly representing the voice of Australian voters.

The Senate: The House of Review

While the House initiates, the Senate scrutinizes. Comprised of 76 senators, with 12 representing each state and 2 each from the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, the Senate acts as a deliberative body, providing a crucial check on the power of the House. Senators are elected for fixed six-year terms, with half the Senate facing re-election every three years, ensuring continuity and stability. The Senate's role is to review, amend, and potentially block legislation passed by the House. This "house of review" function is vital for preventing hasty or partisan legislation and ensuring a more considered approach to lawmaking.

The Legislative Dance: A Delicate Balance

The legislative process in Australia is a complex dance between these two houses. A bill, originating in either house, must be passed by both to become law. This often involves negotiation, compromise, and sometimes, a "double dissolution" where both houses are dissolved and a joint sitting is held to resolve deadlock. This system, while sometimes slow, ensures that legislation is thoroughly debated and reflects the diverse interests of the Australian population.

Practical Implications: How It Affects You

Understanding the roles of the House and Senate is crucial for engaging with Australian politics. When a policy issue matters to you, track its progress through both houses. Contact your local member in the House of Representatives to voice your opinion, and engage with senators who represent your state or territory. Remember, the Senate's power to amend or block legislation means that even if a bill passes the House, it's not a done deal. This system, while complex, ensures that your voice, through your elected representatives, has a say in shaping the laws that govern Australia.

Comedy in Politics: A Helpful Tool or Harmful Distraction?

You may want to see also

Prime Minister: Powers, responsibilities, and relationship with the Governor-General

The Prime Minister of Australia wields significant power, but it’s not absolute. Their authority is derived from both constitutional conventions and practical political realities. At its core, the Prime Minister’s role is to lead the government, set the national agenda, and act as the public face of Australia’s executive branch. However, this power is exercised within a framework that requires negotiation, coalition-building, and adherence to democratic principles. Unlike presidential systems, the Australian Prime Minister’s authority is deeply intertwined with their party’s support and the confidence of the House of Representatives.

One of the Prime Minister’s key responsibilities is to chair the Cabinet, the central decision-making body of the government. Here, they coordinate policy, manage ministerial portfolios, and ensure the government operates cohesively. The Prime Minister also appoints ministers, allocates portfolios, and can reshuffle the Cabinet as needed. This power to appoint and dismiss ministers is a critical tool for maintaining party discipline and advancing the government’s agenda. Additionally, the Prime Minister represents Australia on the world stage, engaging in international diplomacy and negotiating treaties, though these often require parliamentary approval.

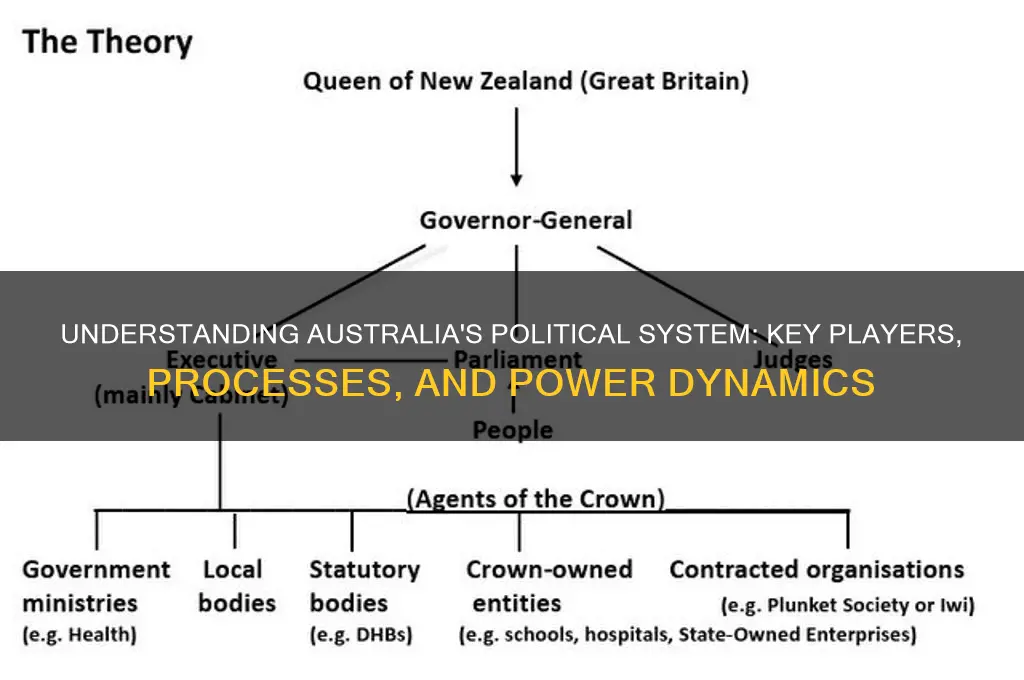

The relationship between the Prime Minister and the Governor-General is both formal and symbolic. The Governor-General, as the monarch’s representative, holds reserve powers that can be exercised in constitutional crises, such as dismissing a government or refusing a request to dissolve Parliament. However, these powers are rarely used and are governed by convention. In practice, the Governor-General acts on the advice of the Prime Minister, who is expected to act in the best interests of the nation. This relationship underscores the principle of responsible government, where the executive is accountable to the elected Parliament, not the Crown.

A practical example of this dynamic occurred in 1975 when Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, citing a budgetary deadlock. While constitutionally valid, the move was highly controversial and highlighted the delicate balance between the Prime Minister’s authority and the Governor-General’s reserve powers. Such instances are rare, but they serve as a reminder that the Prime Minister’s power is not unchecked and is subject to constitutional and political constraints.

In summary, the Prime Minister’s powers and responsibilities are extensive but not unlimited. They lead the government, shape policy, and represent Australia internationally, all while navigating the complexities of party politics and constitutional conventions. Their relationship with the Governor-General is a cornerstone of Australia’s democratic system, embodying the principles of responsible government and the separation of powers. Understanding this dynamic is essential to grasping how politics works in Australia.

Navigating Workplace Politics: Strategies to Foster a Positive Work Environment

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Australia operates as a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with a structure divided into three branches: the executive (led by the Prime Minister and Cabinet), the legislature (Parliament, consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate), and the judiciary (headed by the High Court).

Federal elections in Australia are held at least every three years, as required by the Constitution. However, the Prime Minister can call an election earlier, often referred to as a "snap election."

The Prime Minister is the head of government and the leader of the party or coalition with the majority in the House of Representatives. They appoint ministers, set policy agendas, and represent Australia domestically and internationally.

Australia uses a preferential voting system for the House of Representatives (lower house) and proportional representation for the Senate (upper house). Voters rank candidates in order of preference, and votes are redistributed until a candidate achieves a majority. Voting is compulsory for all eligible citizens.