Political scientists employ a variety of methods to measure variables, ensuring accuracy and reliability in their research. These methods range from quantitative techniques, such as surveys, polls, and statistical analysis of large datasets, to qualitative approaches like interviews, case studies, and content analysis of texts. Each method is chosen based on the nature of the variable being measured—whether it is tangible and easily quantifiable, like voter turnout, or more abstract, like political ideology. Researchers often triangulate multiple methods to validate findings and account for potential biases. Additionally, they carefully operationalize variables, defining them in measurable terms to ensure clarity and consistency. Ethical considerations, such as ensuring participant anonymity and obtaining informed consent, are also integral to the measurement process. By rigorously applying these techniques, political scientists can systematically analyze complex political phenomena and draw evidence-based conclusions.

Explore related products

$124.23 $139

What You'll Learn

- Operationalization: Defining abstract concepts into measurable terms for empirical analysis

- Quantitative Methods: Using numerical data, statistics, and surveys to quantify variables

- Qualitative Methods: Employing interviews, case studies, and observations for in-depth understanding

- Reliability and Validity: Ensuring consistency and accuracy in variable measurement

- Comparative Methods: Analyzing variables across countries, regions, or time periods

Operationalization: Defining abstract concepts into measurable terms for empirical analysis

Political scientists often grapple with abstract concepts like "democracy," "power," or "stability," which are essential for analysis but lack inherent measurability. Operationalization bridges this gap by translating these ideas into concrete, observable indicators. For instance, instead of vaguely assessing "democracy," researchers might operationalize it through specific measures such as election frequency, voter turnout, or the presence of multiple political parties. This process ensures that abstract concepts can be systematically compared across cases and time periods, grounding theory in empirical evidence.

Consider the concept of "political stability." Without operationalization, it remains a subjective term open to interpretation. A researcher might define stability as the absence of violent conflict, operationalizing it by counting the number of conflict-related deaths per year in a country. Alternatively, another might focus on institutional continuity, measuring the frequency of government collapses or leadership changes. These choices are not neutral; they reflect theoretical priorities and shape the analysis. Thus, operationalization requires clarity about the underlying definition and its alignment with research goals.

Operationalization also involves specifying the level of analysis and the tools for measurement. For example, if studying "public opinion," a researcher must decide whether to measure it through surveys, social media sentiment analysis, or legislative voting records. Each method captures a different facet of opinion, with varying degrees of reliability and validity. Surveys might provide direct responses but are limited by sample size and response bias, while social media data offers scale but may skew toward vocal minorities. The choice of measurement tool must balance feasibility, accuracy, and theoretical relevance.

A critical caution in operationalization is the risk of oversimplification. Reducing complex concepts to single indicators can obscure nuance. For instance, measuring "corruption" solely through bribery rates ignores other forms like nepotism or embezzlement. To mitigate this, researchers often use composite indices, combining multiple indicators to capture a concept more comprehensively. For example, the Corruption Perceptions Index incorporates data from various sources, including surveys and expert assessments, to provide a more holistic measure.

In practice, operationalization is both an art and a science. It requires creativity to devise measurable indicators and rigor to ensure they accurately reflect the concept. For instance, when operationalizing "economic inequality," one might use the Gini coefficient, but also supplement it with data on income quintiles or wealth distribution. This multi-faceted approach enhances robustness. Ultimately, effective operationalization hinges on transparency—clearly documenting how concepts are defined and measured—so that others can replicate and critique the analysis. By mastering this process, political scientists transform abstract ideas into tangible data, enabling rigorous empirical inquiry.

Is 'Negroid' Politically Correct? Exploring Language and Racial Sensitivity

You may want to see also

Quantitative Methods: Using numerical data, statistics, and surveys to quantify variables

Political scientists often rely on quantitative methods to transform abstract political phenomena into measurable data. These methods involve assigning numerical values to variables, enabling researchers to analyze relationships, test hypotheses, and draw generalizable conclusions. For instance, instead of simply stating that "voter turnout is high," a quantitative approach might measure turnout as a percentage of eligible voters, allowing for comparisons across elections, regions, or demographic groups. This numerical precision is essential for rigorous empirical research.

To quantify variables, political scientists employ a variety of tools, including surveys, which are a cornerstone of quantitative research. Surveys systematically collect data from a sample of individuals, often using Likert scales (e.g., 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to measure attitudes or behaviors. For example, a survey might ask respondents to rate their trust in government on a scale of 1 to 10. This approach not only standardizes responses but also facilitates statistical analysis, such as calculating averages or identifying correlations between trust in government and voting behavior.

Statistical analysis is another critical component of quantitative methods. Techniques like regression analysis allow researchers to examine how one variable (e.g., income) influences another (e.g., voting preferences) while controlling for confounding factors. For instance, a study might find that higher income levels are associated with a greater likelihood of voting for conservative candidates, even after accounting for education and age. Such analyses provide robust evidence for causal relationships, moving beyond mere observation to explanation.

However, quantitative methods are not without limitations. One challenge is ensuring that numerical data accurately reflect the concepts being measured. For example, using GDP per capita as a proxy for economic well-being may overlook inequalities within a population. Additionally, surveys can suffer from response bias, where certain groups are over- or under-represented. Researchers must carefully design studies, validate measures, and interpret results with caution to mitigate these issues.

In practice, quantitative methods offer a powerful toolkit for political scientists seeking to understand complex phenomena. By combining numerical data, statistics, and surveys, researchers can quantify variables with precision, test theories systematically, and contribute to evidence-based policy-making. For instance, a study measuring the impact of campaign spending on election outcomes can provide actionable insights for candidates and regulators alike. Ultimately, the strength of quantitative methods lies in their ability to transform political questions into empirical problems, yielding answers grounded in data rather than speculation.

Egalitarianism as a Political Philosophy: Principles, Impact, and Debates

You may want to see also

Qualitative Methods: Employing interviews, case studies, and observations for in-depth understanding

Political scientists often turn to qualitative methods when seeking rich, nuanced insights into complex phenomena. Unlike quantitative approaches, which prioritize numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative methods—such as interviews, case studies, and observations—allow researchers to explore the "why" and "how" behind political behaviors, institutions, and processes. These methods are particularly valuable for understanding context, uncovering hidden patterns, and capturing the voices of individuals within political systems.

Consider the use of interviews as a qualitative tool. Structured, semi-structured, or open-ended interviews enable researchers to gather firsthand accounts from key actors, such as policymakers, activists, or voters. For instance, a political scientist studying the impact of grassroots movements might conduct in-depth interviews with organizers to understand their strategies, motivations, and challenges. The key is to design questions that encourage detailed responses while remaining flexible enough to explore emerging themes. Practical tips include building rapport with interviewees, using active listening techniques, and triangulating data by comparing responses across multiple participants.

Case studies offer another powerful qualitative method, particularly for examining specific political events, institutions, or countries in depth. By focusing on a single case or a small number of cases, researchers can uncover causal mechanisms and contextual factors that might be overlooked in broader, quantitative studies. For example, a case study of a successful democratic transition could analyze the roles of leadership, civil society, and international pressure. To maximize validity, researchers should employ systematic data collection, clearly define the boundaries of the case, and consider rival explanations. A cautionary note: while case studies provide depth, their findings may not always generalize to other contexts.

Observations complement interviews and case studies by providing real-time, contextual data on political behavior. Participant observation, where the researcher immerses themselves in the setting, is particularly useful for studying political cultures or informal practices. For instance, observing local government meetings can reveal power dynamics, communication styles, and decision-making processes that might not be apparent in official records. Ethical considerations are crucial here; researchers must obtain informed consent and avoid influencing the behavior of those being observed. Practical advice includes maintaining detailed field notes, reflecting on one’s own biases, and using observational data to corroborate findings from other methods.

In conclusion, qualitative methods—interviews, case studies, and observations—are indispensable tools for political scientists seeking in-depth understanding. Each method has its strengths and limitations, but when used thoughtfully and in combination, they can provide a holistic view of political phenomena. The key is to approach these methods with rigor, creativity, and an awareness of their potential pitfalls, ensuring that the insights gained are both meaningful and reliable.

Mastering Political Warfare: Strategies, Tactics, and Psychological Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Reliability and Validity: Ensuring consistency and accuracy in variable measurement

Political scientists often grapple with the challenge of measuring abstract concepts like democracy, power, or ideology. To ensure their findings are trustworthy, they must prioritize reliability and validity in variable measurement. Reliability refers to the consistency of a measurement—if the same survey question yields similar results across multiple administrations, it’s reliable. Validity, on the other hand, concerns accuracy—does the measurement truly capture what it claims to? For instance, a survey question about "political engagement" should correlate with actual voting behavior, not just self-reported interest. Without both reliability and validity, even the most sophisticated analysis risks being built on shaky foundations.

Consider the measurement of public opinion on climate change. A reliable survey would produce consistent results if repeated under similar conditions, such as using the same question wording and sampling method. However, reliability alone is insufficient. If the survey asks, "Do you care about the environment?" but fails to distinguish between general concern and specific policy support, it lacks validity. To enhance validity, political scientists might employ multi-item scales, such as asking about support for carbon taxes, renewable energy subsidies, and emissions regulations. This approach ensures the measurement aligns with the nuanced concept of climate policy attitudes.

Ensuring reliability and validity requires deliberate methodological choices. For reliability, researchers can conduct test-retest assessments, administering the same measure at different times to check for consistency. Alternatively, internal consistency checks, like Cronbach’s alpha, assess whether multiple survey items intended to measure the same concept yield correlated responses. For validity, face validity (does the measure appear to capture the concept?) is a starting point, but more rigorous methods like construct validity (does the measure correlate with theoretically related variables?) are essential. For example, a measure of authoritarianism should correlate positively with support for strong leadership and negatively with tolerance for dissent.

Practical challenges abound. In cross-national studies, translating survey questions into multiple languages can threaten reliability if nuances are lost. To mitigate this, back-translation—translating the survey into the target language and then back into the original—can identify discrepancies. Validity is particularly tricky when measuring latent constructs like "political trust." Here, triangulation—using multiple data sources, such as surveys, interviews, and behavioral data—can strengthen confidence in the measurement. For instance, combining self-reported trust in government with data on tax compliance provides a more robust assessment.

Ultimately, reliability and validity are not one-time achievements but ongoing priorities. As political contexts evolve, so must measurement tools. For example, a survey question about "media consumption" that once focused on newspapers and television must now account for social media and podcasts to remain valid. By rigorously assessing and refining their measures, political scientists ensure their research not only stands up to scrutiny but also contributes meaningfully to understanding complex political phenomena. Without this foundation, even the most elegant theories risk being built on quicksand.

Avoiding Political Debates: Strategies to Steer Conversations Away from Politics

You may want to see also

Comparative Methods: Analyzing variables across countries, regions, or time periods

Political scientists often employ comparative methods to analyze variables across countries, regions, or time periods, seeking patterns, causal relationships, or deviations that inform broader theories. For instance, when examining the impact of electoral systems on voter turnout, researchers might compare proportional representation systems in Scandinavia with majoritarian systems in the United Kingdom. This approach allows them to isolate the effect of the electoral system while controlling for other factors, such as cultural norms or socioeconomic development. By systematically comparing cases, scholars can move beyond anecdotal evidence to draw more robust conclusions.

To effectively use comparative methods, researchers must carefully select cases that maximize analytical leverage. This involves choosing countries, regions, or time periods that vary on the independent variable of interest but share other relevant characteristics. For example, a study on the relationship between income inequality and democratic stability might compare Brazil and South Africa—both middle-income democracies with histories of inequality—to highlight how differing policy responses affect outcomes. This "most similar systems" design minimizes confounding variables, making it easier to attribute observed differences to the variable under study.

However, comparative methods are not without challenges. One major issue is the trade-off between internal and external validity. Small-N studies (e.g., comparing two or three countries) often provide rich, context-specific insights but struggle to generalize findings. In contrast, large-N studies (e.g., analyzing 50 countries) enhance generalizability but may oversimplify complex realities. For instance, a cross-national study on corruption might find that higher GDP per capita correlates with lower corruption, but it may overlook how cultural norms or institutional legacies shape this relationship in specific contexts. Researchers must therefore balance depth and breadth, often combining qualitative and quantitative techniques to triangulate findings.

Practical tips for implementing comparative methods include leveraging existing datasets like the World Bank’s World Development Indicators or the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project, which provide standardized measures across countries and time periods. When constructing indices (e.g., measuring democracy or governance quality), ensure transparency in variable weighting and aggregation methods. Additionally, employ sensitivity analyses to test how robust findings are to alternative case selections or measurement strategies. For example, if studying the effect of decentralization on public service delivery, compare results using different decentralization indices to assess consistency.

In conclusion, comparative methods are a cornerstone of political science, offering a structured way to analyze variables across diverse contexts. By thoughtfully selecting cases, balancing methodological trade-offs, and leveraging existing data, researchers can uncover meaningful insights into political phenomena. Whether exploring the roots of political instability or the drivers of policy innovation, this approach equips scholars to navigate complexity and contribute to evidence-based understanding.

Reggae's Political Pulse: How Music Shaped Social Change and Resistance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political scientists use quantitative and qualitative methods, including surveys, experiments, content analysis, observational studies, and statistical analysis, to measure variables.

Reliability is ensured through consistent measurement techniques, pilot testing, inter-coder agreement (for qualitative data), and using validated scales or indices.

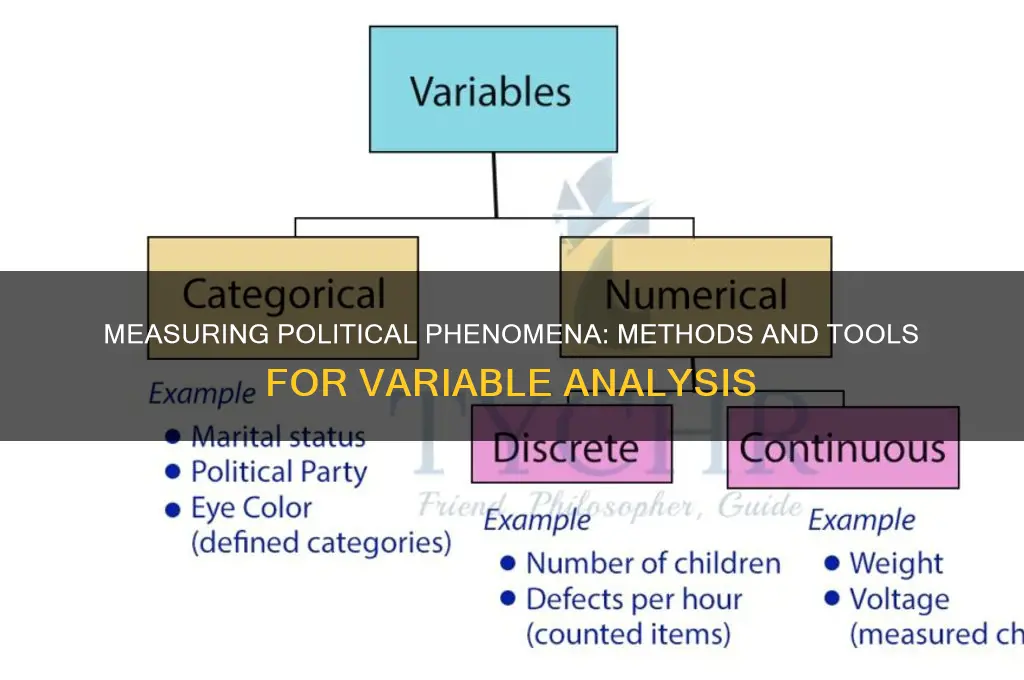

Nominal variables measure categories (e.g., party affiliation), ordinal variables measure ranked categories (e.g., levels of agreement), and interval variables measure equal intervals (e.g., temperature or income).

They minimize bias through clear operationalization, transparent methods, peer review, and triangulation (using multiple data sources or methods to cross-verify findings).