The evolution of political parties in the United States after 1783 marked a transformative shift in the nation’s political landscape, emerging from the initial skepticism of party factions during the Revolutionary era. Following the ratification of the Constitution in 1787, ideological divisions between Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and Anti-Federalists, championed by figures like Thomas Jefferson, laid the groundwork for the first party system. The Federalists advocated for a strong central government and close ties with Britain, while the Democratic-Republicans, as Jefferson’s faction became known, emphasized states’ rights, agrarian interests, and democratic ideals. By the early 1800s, these factions solidified into the first modern political parties, with the Democratic-Republicans dominating after the election of 1800, often referred to as the Revolution of 1800. This period not only institutionalized party politics but also set the stage for the two-party system that continues to shape American governance today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Early Formation (1780s-1790s) | Emergence of the Federalist Party (pro-strong central government) and the Democratic-Republican Party (pro-states' rights) under Washington's presidency. |

| Two-Party System Begins (1800s) | Solidification of the two-party system with Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans, culminating in the election of 1800. |

| Second Party System (1820s-1850s) | Rise of the Democratic Party (led by Andrew Jackson) and the Whig Party, focusing on economic policies and westward expansion. |

| Civil War Era (1850s-1860s) | Collapse of the Whig Party; emergence of the Republican Party (anti-slavery) and realignment over slavery issues. |

| Post-Civil War (1860s-1900s) | Dominance of the Republican Party in the North and the Democratic Party in the South, with focus on Reconstruction and industrialization. |

| Progressive Era (1900s-1920s) | Parties adopted progressive reforms, with Theodore Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party and the rise of third-party movements. |

| New Deal Era (1930s-1940s) | Democratic Party realignment under FDR, with the New Deal coalition (labor, minorities, intellectuals) and Republican shift to conservatism. |

| Civil Rights Era (1950s-1960s) | Democrats embraced civil rights, leading to Southern conservatives shifting to the Republican Party (Southern Strategy). |

| Modern Era (1970s-Present) | Polarization increased, with Republicans dominating conservative policies and Democrats focusing on social liberalism. |

| Third-Party Influence | Occasional third-party candidates (e.g., Ross Perot, Ralph Nader) but limited success in winning elections. |

| Technological Impact | Social media and digital campaigns transformed party outreach and fundraising strategies. |

| Demographic Shifts | Changing demographics (e.g., growing minority populations) influenced party platforms and voter bases. |

| Ideological Polarization | Increasing divide between liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans on issues like healthcare, immigration, and climate change. |

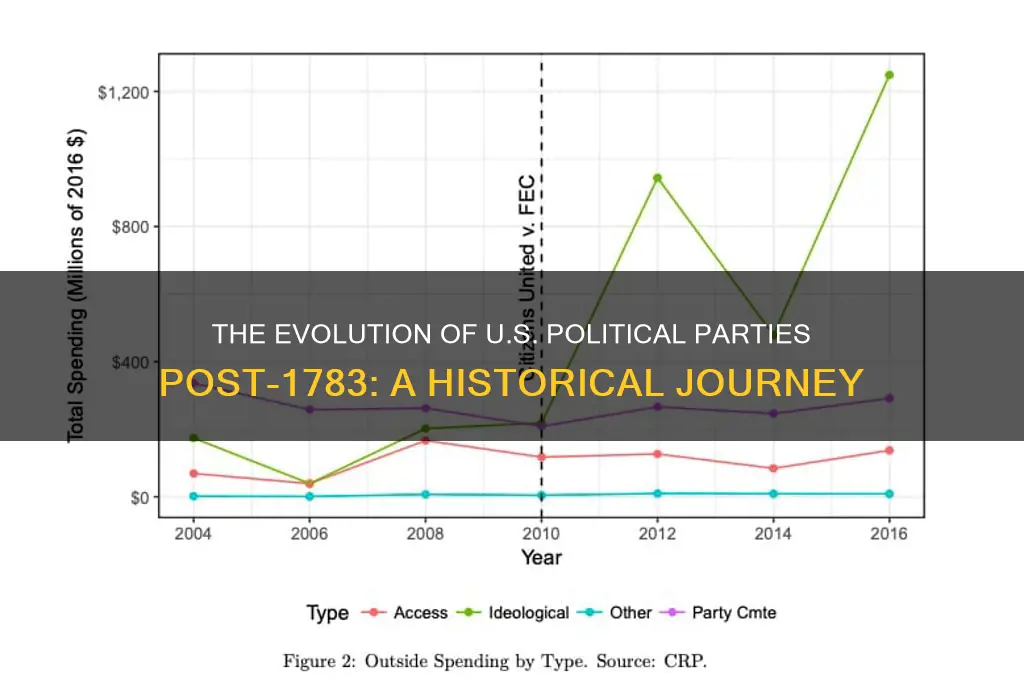

| Role of Money in Politics | Rise of Super PACs and corporate donations shaping party agendas and election outcomes. |

| Global Influence | Parties adapted to global issues like trade, terrorism, and climate change, influencing foreign policy platforms. |

Explore related products

$35.53 $61.99

$68.37 $74

What You'll Learn

Emergence of Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787 marked a pivotal moment in American political history, but it also exposed deep divisions within the young nation. The debate over the Constitution’s adoption gave rise to two distinct factions: the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists. These groups, though united by a desire to shape the nation’s future, clashed over fundamental questions of governance, power, and individual rights. Their emergence laid the groundwork for the country’s first political parties and set the stage for ongoing debates about federal authority versus states’ rights.

Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, championed the Constitution as a necessary framework for a strong central government. They argued that the Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first governing document, had left the country weak and disunited. Through a series of essays known as *The Federalist Papers*, they made a persuasive case for ratification, emphasizing the need for stability, economic growth, and national defense. Federalists envisioned a federal government with sufficient power to regulate commerce, collect taxes, and maintain order—a stark contrast to the decentralized system under the Articles. Their influence was particularly strong among urban merchants, creditors, and elites who stood to benefit from a more unified and economically robust nation.

Anti-Federalists, on the other hand, viewed the Constitution with suspicion, fearing it would concentrate power in the hands of a distant federal government at the expense of state sovereignty and individual liberties. Prominent figures like Patrick Henry and George Mason argued that the Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights and could lead to tyranny. They championed the rights of ordinary citizens, particularly farmers and rural populations, who were wary of a strong central authority. Anti-Federalists believed that power should remain closer to the people, vested in state governments that were more accountable to local needs. Their opposition was not merely ideological but rooted in practical concerns about representation and the potential for federal overreach.

The clash between Federalists and Anti-Federalists was not just a theoretical debate but a practical struggle with immediate consequences. The ratification process itself became a battleground, with Federalists securing victories in key states like Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, while Anti-Federalists delayed ratification in others. The compromise that emerged—the promise of a Bill of Rights—was a direct result of Anti-Federalist pressure and ensured the Constitution’s eventual adoption. This compromise also highlighted the evolving nature of American politics, where negotiation and concession became essential tools for resolving ideological differences.

The legacy of Federalists and Anti-Federalists extends beyond their immediate impact on the Constitution. Their debates framed enduring questions about the balance of power in American governance. Federalists’ vision of a strong central government laid the foundation for the modern administrative state, while Anti-Federalists’ emphasis on individual rights and local control continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about federalism. Together, these factions demonstrated that political parties could emerge not just from shared interests but from principled disagreements about the nation’s core values. Their emergence was a testament to the dynamism of American democracy, where conflict and compromise coexist as driving forces of political evolution.

Can You Deduct Political Party Membership Fees on Your Taxes?

You may want to see also

Rise of Democratic-Republican Party

The emergence of the Democratic-Republican Party in the late 18th century marked a pivotal shift in American political ideology, rooted in a direct response to the Federalist Party’s centralizing policies. Founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the party championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. This contrasted sharply with the Federalists, who favored a strong national government, industrialization, and loose constitutional interpretation. The Democratic-Republicans capitalized on growing public unease with Federalist policies like the Alien and Sedition Acts, which many viewed as threats to individual liberties. By framing themselves as defenders of the common man against elite dominance, they built a broad coalition of farmers, artisans, and frontier settlers, setting the stage for their rise to power.

To understand the party’s appeal, consider its strategic messaging and organizational tactics. Jefferson’s 1800 presidential campaign, often called the "Revolution of 1800," exemplified this approach. The party mobilized voters through newspapers, pamphlets, and public meetings, accusing Federalists of monarchical tendencies and portraying themselves as guardians of republican values. For instance, Jefferson’s inaugural address emphasized "the will of the majority" and a return to limited government, resonating deeply with a populace wary of federal overreach. This blend of ideological clarity and grassroots engagement proved effective, as the Democratic-Republicans secured control of both the presidency and Congress, ending Federalist dominance.

A comparative analysis reveals the party’s long-term impact on American politics. While the Federalists faded after the War of 1812, the Democratic-Republicans evolved into the modern Democratic Party, shaping political discourse for decades. Their emphasis on states’ rights and agrarianism influenced policies like the Louisiana Purchase and the eventual rise of Jacksonian democracy. However, their legacy is not without controversy. The party’s commitment to states’ rights often clashed with efforts to address national issues, a tension that persists in contemporary debates over federalism. Practical takeaways include the importance of aligning political platforms with public sentiment and the enduring power of grassroots organizing in electoral success.

Finally, the rise of the Democratic-Republican Party underscores a critical lesson in political evolution: adaptability and responsiveness to societal changes are key to survival. By identifying and addressing the concerns of a diverse electorate, Jefferson and Madison transformed American politics. Their success serves as a blueprint for modern parties seeking to navigate shifting demographics and ideological landscapes. For those studying political history or engaging in activism, the Democratic-Republicans’ story highlights the value of clear messaging, coalition-building, and a deep understanding of the electorate’s priorities.

Failed Political Coalitions: Analyzing Broken Alliances and Their Consequences

You may want to see also

Era of Good Feelings and One-Party Rule

The Era of Good Feelings, spanning from 1815 to 1825, marked a unique period in American political history characterized by the dominance of a single party—the Democratic-Republicans. This era emerged in the aftermath of the War of 1812, a conflict that fostered a sense of national unity and pride, temporarily sidelining partisan divisions. President James Monroe’s administration epitomized this period, as he ran virtually unopposed in the 1820 election, symbolizing the apparent harmony and one-party rule. However, beneath the surface of this political tranquility lay simmering tensions and ideological shifts that would soon reshape the party system.

To understand this era, consider it as a political interlude—a pause in the partisan warfare that had defined earlier decades. The Federalist Party, once a formidable force, collapsed due to its opposition to the War of 1812 and its association with secessionist sentiments in New England. This left the Democratic-Republicans, led by figures like Monroe and former President James Madison, as the sole national party. The absence of opposition allowed the Democratic-Republicans to consolidate power, but it also masked growing regional and ideological differences within their own ranks. For instance, while the party championed states’ rights and limited federal government, these principles were interpreted differently in the agrarian South and the industrializing North.

A key takeaway from this period is the illusion of unity it presented. The Era of Good Feelings was not a time of genuine political consensus but rather a moment when dissent was muted by external circumstances. Practical examples include the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which temporarily resolved the issue of slavery in new states but exposed deep divisions over the issue. This compromise was less a triumph of unity and more a fragile truce, highlighting the challenges of maintaining one-party rule in a diverse and expanding nation.

As the era progressed, the seeds of future partisan conflict were sown. The rise of new leaders like John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, along with emerging issues such as tariffs, internal improvements, and the role of the federal government, began to fracture the Democratic-Republican Party. By the late 1820s, the Second Party System emerged, with the Democratic-Republicans splitting into the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. This evolution underscores a critical lesson: one-party rule, while seemingly stable, often conceals underlying tensions that eventually demand resolution through renewed political competition.

In retrospect, the Era of Good Feelings serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of political monopolies. While it offered a temporary respite from partisan strife, it also delayed the reckoning of fundamental disagreements that would define American politics for decades. For modern observers, this period illustrates the importance of healthy political competition in addressing societal divisions and fostering democratic resilience. Without opposition, even the most dominant parties risk becoming complacent, failing to adapt to the evolving needs and values of the nation.

Income's Impact: Shaping Political Party Loyalty and Voting Patterns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Second Party System: Whigs vs. Democrats

The Second Party System, emerging in the 1830s and lasting until the mid-1850s, pitted the Whig Party against the Democratic Party in a battle of contrasting visions for America’s future. At its core, this era was defined by debates over economic development, the role of government, and the balance of power between states and the federal authority. The Whigs, led by figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, championed federal investment in infrastructure, protective tariffs, and a national bank, viewing these as essential tools for fostering economic growth. In contrast, the Democrats, under Andrew Jackson and later successors, emphasized limited government, states’ rights, and agrarian interests, often portraying Whig policies as favoring the elite at the expense of the common man.

To understand the Whigs’ perspective, consider their "American System," a three-pronged economic plan: tariffs to protect domestic industries, a national bank to stabilize currency, and federally funded internal improvements like roads and canals. This approach reflected their belief in an active government role in shaping the nation’s economic destiny. For instance, the Whigs supported the 1842 Tariff of Protection, which raised import duties to shield American manufacturers from foreign competition. Democrats, however, vehemently opposed such measures, arguing they disproportionately benefited northern industrialists while burdening southern farmers and western settlers with higher costs.

The Democrats’ appeal lay in their populist rhetoric and commitment to individual liberty. They championed the expansion of democracy, as seen in their support for the removal of property qualifications for voting and their opposition to what they termed "special privileges" for corporations. Jackson’s dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States in 1833 symbolized their distrust of centralized financial power. Yet, this stance often clashed with the realities of a rapidly industrializing nation, where infrastructure and financial stability were increasingly vital.

A key takeaway from this period is how these parties reflected regional divisions. Whigs dominated the Northeast, where industrialization thrived, while Democrats found their stronghold in the agrarian South and frontier West. These regional interests shaped policy debates, such as those over the expansion of slavery into new territories, which would later contribute to the system’s collapse. By the 1850s, the issue of slavery transcended economic and regional disputes, leading to the fragmentation of both parties and the rise of the Republican Party.

In practical terms, the Second Party System offers a lens for understanding modern political polarization. Whigs and Democrats were not merely ideological opponents but representatives of distinct societal groups with competing needs. Today, policymakers can learn from this era by recognizing how economic policies must balance regional and class interests to avoid alienating large segments of the population. For historians and political analysts, studying this period provides insights into how parties evolve in response to technological, economic, and social changes—lessons as relevant now as they were in the 19th century.

Reviving Political Prose: Escaping the Bland and Lifeless Writing Trap

You may want to see also

Post-Civil War: Republican Dominance and Realignment

The post-Civil War era marked a seismic shift in American political party dynamics, solidifying Republican dominance and reshaping the nation's ideological landscape. The Republican Party, born in the 1850s as a coalition opposed to the expansion of slavery, emerged from the war as the party of Union victory and national reunification. This triumph, coupled with the Democrats' association with the defeated Confederacy, granted the Republicans a significant advantage in the political arena.

The period witnessed a dramatic realignment of party loyalties, particularly in the South. Formerly Democratic strongholds, now under Republican control through Reconstruction policies, saw African Americans, newly enfranchised by the 15th Amendment, overwhelmingly support the GOP. This shift, while empowering a previously marginalized group, also fueled white Southern resentment and laid the groundwork for future political realignments.

This Republican dominance wasn't merely a product of wartime victory. The party's platform, centered on economic modernization, industrialization, and national unity, resonated with a nation rebuilding itself. Policies like the Homestead Act, promoting westward expansion, and investments in railroads and infrastructure, aligned with the aspirations of a growing middle class and burgeoning industrial sector. The Republicans' ability to capitalize on these economic trends further cemented their hold on power.

However, this dominance wasn't without its complexities. Internal divisions within the Republican Party, particularly over the extent of Reconstruction efforts and the role of government in economic affairs, began to emerge. These fissures, though not immediately threatening their hold on power, foreshadowed future challenges and the eventual erosion of their monolithic control.

Understanding this post-Civil War realignment is crucial for comprehending the enduring legacy of the Republican Party and the broader trajectory of American politics. It highlights the interplay between historical events, ideological shifts, and demographic changes in shaping party systems. The Republican dominance of this era, while not permanent, left an indelible mark on the nation's political landscape, influencing policy debates and party identities for generations to come.

Understanding Sexual Politics: Power, Gender, and Society's Complex Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first political parties emerged in the 1790s, primarily as the Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson. The Federalists supported a strong central government and close ties with Britain, while the Democratic-Republicans advocated for states' rights and agrarian interests.

The War of 1812 led to the decline of the Federalist Party, as their opposition to the war alienated many Americans. The Democratic-Republican Party, under James Madison, gained dominance, and the "Era of Good Feelings" followed, marked by a temporary one-party system until the emergence of new factions in the 1820s.

The modern two-party system began to take shape in the 1820s and 1830s with the rise of the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which later evolved into the Republican Party. This shift was driven by issues like states' rights, tariffs, and the expansion of democracy.

The issue of slavery deeply divided political parties, leading to the collapse of the Whig Party and the emergence of the Republican Party in the 1850s. The Democratic Party split between northern and southern factions, while the Republicans, led by Abraham Lincoln, opposed the expansion of slavery, setting the stage for the Civil War.