Karl Marx understands politics as an integral component of the broader socioeconomic structure, rooted in the material conditions of society. For Marx, politics is not an autonomous sphere but a superstructure shaped by the underlying economic base, particularly the relations of production and class struggle. He argues that the state and political institutions serve the interests of the dominant class, which, under capitalism, is the bourgeoisie, to maintain and reproduce the existing mode of production. Marx views politics as a site of conflict and transformation, where the oppressed proletariat must organize to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a classless society. Thus, his understanding of politics is deeply tied to his critique of capitalism and his vision of a revolutionary transition to socialism and communism.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Materialist Base | Marx views politics as a superstructure built upon the economic base of society. The mode of production (relations between classes and ownership of means of production) determines the political system. |

| Class Struggle | Politics is fundamentally driven by the conflict between opposing classes with conflicting economic interests. The ruling class uses politics to maintain its dominance, while the oppressed class seeks to overthrow it. |

| State as Instrument | The state is not a neutral arbiter but a tool of the ruling class to enforce its will and suppress the oppressed class. |

| Historical Materialism | Political systems are not static but evolve through historical stages driven by class struggle and changes in the mode of production. |

| Revolutionary Change | Marx believes capitalism inherently contains contradictions that will lead to its downfall through proletarian revolution, resulting in a classless society. |

| Dictatorship of the Proletariat | A transitional phase after revolution where the working class holds political power to suppress the bourgeoisie and establish socialism. |

| Withering Away of the State | In a communist society, class distinctions disappear, rendering the state unnecessary, and it eventually withers away. |

| Internationalism | Marx saw the struggle for socialism as a global one, transcending national boundaries. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Class Struggle: Marx sees politics as a reflection of class conflict, shaping power dynamics

- State as Tool: The state serves the ruling class, maintaining capitalist dominance and control

- Ideology Critique: Politics is influenced by dominant ideologies masking class exploitation

- Revolutionary Change: Marx advocates for proletarian revolution to overthrow capitalist political structures

- Economic Base: Political superstructure arises from economic relations, driven by material conditions

Class Struggle: Marx sees politics as a reflection of class conflict, shaping power dynamics

Karl Marx’s understanding of politics is rooted in the concept of class struggle, a dynamic he saw as the engine of historical change. For Marx, politics is not a neutral arena but a battleground where the interests of opposing classes clash. The ruling class, which controls the means of production, uses political institutions to maintain its dominance, while the oppressed class fights to overturn this hierarchy. This conflict is not merely economic but fundamentally shapes the structure of power, law, and governance. Politics, in Marx’s view, is the superstructure erected on the base of economic relations, reflecting and reinforcing class divisions.

Consider the Industrial Revolution, a period Marx analyzed extensively. Factory owners amassed wealth by exploiting workers, who labored long hours for meager wages. The political system of the time—with its limited suffrage, pro-business laws, and suppression of labor movements—was designed to protect the interests of the capitalist class. This example illustrates Marx’s point: politics is not a disinterested mediator but a tool wielded by the dominant class to secure its position. The struggle between capitalists and workers was not just about wages but about control over the political machinery itself.

To understand this dynamic, imagine politics as a stage where the script is written by the economically powerful. Laws, policies, and even cultural norms are crafted to legitimize their rule. For instance, property rights are enshrined as sacred, not because they are inherently just, but because they protect the wealth of the ruling class. Meanwhile, the working class is often portrayed as either a threat or a passive beneficiary of the system, obscuring their potential as agents of change. This framing is not accidental; it is a deliberate strategy to maintain the status quo.

Marx’s analysis offers a practical takeaway: to challenge political power, one must first address its economic roots. Labor movements, for example, have historically sought not just better wages but also political reforms that redistribute power. The eight-hour workday, a demand achieved through strikes and protests, was not merely an economic victory but a political one, reshaping the balance of power between workers and employers. Similarly, modern movements like the Fight for $15 campaign in the U.S. are not just about wages but about dismantling the political structures that perpetuate inequality.

However, Marx’s framework is not without cautionary notes. Reducing politics solely to class struggle risks oversimplifying complex issues like race, gender, and colonialism, which intersect with but are not identical to class. For instance, the civil rights movement in the U.S. fought against racial oppression, which, while tied to economic exploitation, had its own distinct dynamics. Marx’s theory is most powerful when used as a lens rather than a rigid formula, allowing for the incorporation of other forms of oppression into the analysis of power.

In conclusion, Marx’s view of politics as a reflection of class struggle remains a vital tool for understanding power dynamics. By exposing the economic foundations of political systems, it empowers individuals to see beyond surface-level policies and identify the underlying structures of control. Whether analyzing historical revolutions or contemporary movements, this perspective encourages a critical approach to politics, urging us to ask: *whose interests does this system serve, and how can we transform it?*

Navigating Political Tensions: Strategies to Manage Anger and Foster Dialogue

You may want to see also

State as Tool: The state serves the ruling class, maintaining capitalist dominance and control

Karl Marx views the state not as a neutral arbiter but as a weapon forged and wielded by the ruling class to safeguard their economic dominance. This perspective, central to his critique of capitalism, reveals the state's role in perpetuating a system that inherently favors the wealthy few. Through laws, institutions, and ideological apparatuses, the state actively suppresses challenges to capitalist hegemony, ensuring the continued exploitation of the working class.

Marxist analysis exposes the state's function as a tool for class oppression, a far cry from its purported role as a representative of the "general will."

Consider the legal framework within capitalist societies. Laws governing property rights, contracts, and labor relations are not impartial; they are meticulously crafted to protect private ownership and the interests of capital. For instance, intellectual property laws grant monopolies to corporations, stifling innovation and benefiting those who already possess wealth. Similarly, labor laws often prioritize business interests over worker rights, limiting strikes and collective bargaining power. This legal scaffolding, erected by the state, systematically disadvantages the working class, ensuring their continued subservience to the capitalist system.

The state's role in education further exemplifies its service to the ruling class. Curricula are designed to instill values conducive to capitalist production, emphasizing individualism, competition, and obedience to authority. History is often sanitized, erasing the struggles of the working class and glorifying the achievements of the wealthy. This ideological indoctrination ensures that future generations internalize the existing power structure as natural and inevitable, hindering the development of a critical consciousness that could challenge capitalist dominance.

Understanding the state as a tool of the ruling class is not merely an academic exercise; it's a call to action. It demands that we critically examine the institutions and ideologies that shape our lives. By recognizing the state's complicity in maintaining capitalist oppression, we can begin to envision alternative forms of social organization that prioritize collective well-being over private profit. This requires challenging the legitimacy of the state's authority and building movements that empower the working class to reclaim control over their lives and labor.

Is Morgan Wallen Political? Unraveling the Country Star's Views and Stance

You may want to see also

Ideology Critique: Politics is influenced by dominant ideologies masking class exploitation

Marx's critique of ideology reveals a stark reality: politics is not a neutral arena but a battleground where dominant ideologies perpetuate class exploitation under the guise of fairness and order. This insight is not merely theoretical; it is a call to action for those seeking to understand and challenge the status quo. Consider the concept of "hegemony," a term popularized by Antonio Gramsci, which describes how the ruling class’s ideas become the norm, shaping societal beliefs and practices. For instance, the ideology of meritocracy suggests that anyone can succeed through hard work, yet it obscures systemic barriers that favor the wealthy. This narrative masks the exploitation of the working class by framing inequality as a result of individual failure rather than structural injustice.

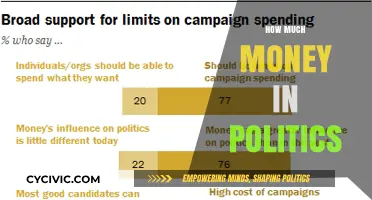

To dissect this mechanism, examine how political discourse often revolves around abstract ideals like "freedom" or "national unity." These concepts, while appealing, serve to divert attention from material realities. For example, tax policies favoring corporations are justified as necessary for economic growth, even as they exacerbate wealth inequality. Marx would argue that such policies are not neutral but are designed to maintain the dominance of the capitalist class. The ideology critique, therefore, is a tool to expose these hidden agendas, urging us to question whose interests are truly served by political decisions.

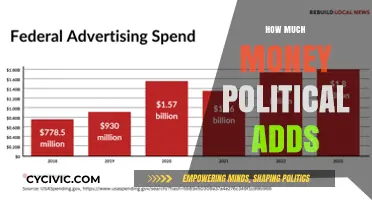

A practical step in applying Marx’s ideology critique is to analyze media narratives critically. Media outlets, often owned by or aligned with the ruling class, play a pivotal role in disseminating dominant ideologies. For instance, during labor disputes, workers’ demands are frequently portrayed as disruptive, while corporate interests are framed as rational and necessary. To counter this, engage in media literacy by seeking alternative sources and questioning the framing of issues. For example, instead of accepting that a strike is harmful to the economy, ask how corporate profits are distributed and why workers feel compelled to strike in the first place.

Comparatively, Marx’s approach contrasts sharply with liberal theories that view politics as a neutral process of interest aggregation. While liberals focus on procedural fairness, Marx emphasizes the material conditions that underpin political systems. This comparative lens highlights the limitations of reforms that do not address class exploitation. For instance, increasing minimum wage without challenging the capitalist system may alleviate immediate suffering but does not dismantle the structures that create inequality. Thus, Marx’s critique encourages a more radical rethinking of politics, one that targets the root causes of exploitation rather than its symptoms.

In conclusion, Marx’s ideology critique offers a powerful framework for understanding how politics is shaped by dominant ideologies that mask class exploitation. By exposing these mechanisms, individuals can move beyond surface-level analyses and engage in transformative action. Whether through critical media consumption, questioning political narratives, or advocating for systemic change, this critique equips us with the tools to challenge the status quo. The takeaway is clear: politics is not a neutral game but a site of struggle where ideologies are wielded to maintain power. Recognizing this is the first step toward building a more just society.

Do Politicians Respond to CD: Analyzing Campaign Donation Influence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Revolutionary Change: Marx advocates for proletarian revolution to overthrow capitalist political structures

Karl Marx's understanding of politics is deeply rooted in his critique of capitalism and his vision for a proletarian revolution. At the heart of his political theory is the belief that the capitalist system inherently exploits the working class, or proletariat, by extracting surplus value from their labor. This exploitation, Marx argues, is not merely an economic issue but a political one, as it perpetuates a power structure where the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class) controls the means of production and, consequently, the political apparatus. To dismantle this oppressive system, Marx advocates for a revolutionary overthrow of capitalist political structures by the proletariat, leading to the establishment of a classless society.

To achieve this revolutionary change, Marx outlines a process that begins with the proletariat's awareness of its collective power. He posits that as workers recognize their shared exploitation, they will develop class consciousness—an understanding of their common interests and the need to unite against the bourgeoisie. This consciousness is not spontaneous but is fostered through the material conditions of capitalism itself, which increasingly polarize society into two antagonistic classes. For instance, the industrialization of the 19th century, as observed in Marx's time, led to the concentration of workers in factories, facilitating the spread of revolutionary ideas and solidarity. Practical steps toward fostering class consciousness today might include organizing labor unions, engaging in workplace activism, and utilizing social media to amplify workers' voices and grievances.

Marx's advocacy for revolution is not merely destructive but transformative. He argues that the proletarian revolution is a necessary step to dismantle the capitalist state, which he views as an instrument of class oppression. In its place, Marx envisions a dictatorship of the proletariat—a transitional phase where the working class holds political power to restructure society. This phase is crucial for abolishing private ownership of the means of production and establishing a socialist economy. Critics often misinterpret this concept as authoritarian, but Marx emphasizes its temporary and democratic nature, serving as a bridge to a stateless, classless society. A cautionary note is that historical attempts to implement this phase, such as in the Soviet Union, often devolved into bureaucratic authoritarianism, highlighting the need for vigilant democratic practices within revolutionary movements.

Comparatively, Marx's approach to revolutionary change contrasts sharply with reformist strategies that seek to improve capitalism from within. While reforms like labor laws or welfare programs may alleviate immediate suffering, Marx argues they do not address the systemic roots of exploitation. For example, the eight-hour workday, a reform achieved through labor struggles, improved workers' conditions but did not challenge capitalist ownership. Marx's revolutionary vision, however, seeks to uproot the system entirely, redistributing power and resources to those who create wealth. This comparative perspective underscores the radical nature of Marx's politics, which prioritizes fundamental transformation over incremental change.

In practical terms, advocating for proletarian revolution today requires a nuanced understanding of contemporary capitalism. Globalization has dispersed production across borders, complicating traditional notions of the working class. Modern revolutionaries must therefore focus on building international solidarity among workers, addressing issues like outsourcing and precarious labor. Additionally, incorporating intersectional analysis—recognizing how race, gender, and other identities intersect with class—is essential for inclusive mobilization. For instance, movements like the Fight for $15 in the U.S. have successfully united low-wage workers across diverse backgrounds, demonstrating the potential for broad-based revolutionary organizing. Marx's call for revolutionary change remains relevant, but its application must adapt to the complexities of the 21st century.

Has Politics Ruined California? A Critical Analysis of the Golden State's Decline

You may want to see also

Economic Base: Political superstructure arises from economic relations, driven by material conditions

Karl Marx posits that the economic base, or the mode of production, is the foundation upon which the political superstructure is built. This relationship is not merely coincidental but causal: the material conditions of society, defined by its economic relations, dictate the nature of its political institutions, laws, and ideologies. For instance, in a capitalist society, where the means of production are privately owned, the political system tends to favor the interests of the bourgeoisie, the ruling class that controls these means. This is evident in policies that protect private property, deregulate markets, and minimize labor rights, all of which serve to maintain the dominance of capital over labor.

To understand this dynamic, consider the process of lawmaking in a capitalist economy. Laws are not neutral tools but instruments shaped by the prevailing economic relations. For example, intellectual property laws are designed to protect patents and copyrights, benefiting corporations that rely on innovation and branding. Similarly, tax policies often favor the wealthy through loopholes and lower rates on capital gains, reinforcing economic inequality. These legal frameworks are not arbitrary but are directly tied to the material interests of the ruling class, illustrating how the economic base determines the political superstructure.

Marx’s framework is not deterministic but analytical, offering a lens to critique and understand power structures. By examining the economic base, one can predict the political outcomes of a society. For instance, in feudal systems, where landownership defined wealth, political power was concentrated among the nobility. The transition to capitalism disrupted this structure, replacing feudal lords with industrial capitalists and reshaping political institutions accordingly. This historical materialist approach allows us to trace the evolution of politics as a reflection of changing economic conditions.

A practical application of this theory can be seen in the analysis of labor movements. When workers organize to demand better wages or safer conditions, they are challenging the economic base of capitalism, which relies on the exploitation of labor. The political superstructure responds through legislation, either suppressing these movements (e.g., anti-union laws) or co-opting them (e.g., labor reforms). This interplay demonstrates how political actions are ultimately rooted in economic struggles, reinforcing Marx’s argument that the superstructure is a product of the base.

Finally, Marx’s concept invites us to question the autonomy of political systems. It challenges the notion that politics operates independently of economics, revealing how material conditions shape governance. For activists and policymakers, this insight is crucial: addressing political issues requires confronting the underlying economic structures. For example, combating systemic inequality cannot be achieved through political reforms alone but demands a transformation of the economic base itself. This perspective shifts the focus from superficial changes to fundamental restructuring, offering a more radical and effective approach to social change.

Polite Reminder Strategies: How to Approach Your Manager Effectively

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Marx sees politics as a superstructure that arises from the economic base (mode of production). He argues that political institutions, laws, and ideologies are shaped by the underlying economic relations and class struggles within a society.

Marx views the state as an instrument of class domination, serving the interests of the ruling class. In capitalist societies, the state functions to maintain and reproduce the conditions for capitalist exploitation, even if it appears neutral.

Marx sees class struggle as the engine of political change. Politics, for Marx, is fundamentally about the conflict between opposing classes (e.g., bourgeoisie and proletariat), with the state and political institutions reflecting this struggle.

Marx critiques reformism, arguing that it fails to address the root causes of exploitation within capitalism. Instead, he advocates for a revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system and the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat as a transitional phase to communism.

Marx argues that ideology is a tool used by the ruling class to justify and maintain its dominance. Political ideologies, according to Marx, often mask the true nature of class relations and serve to reproduce the existing power structure.