The representation of women in politics remains a critical indicator of gender equality and democratic progress worldwide. Despite significant advancements in recent decades, women are still underrepresented in political leadership roles across most countries. As of recent data, women hold only about 26% of parliamentary seats globally, and only a handful of nations have achieved gender parity in government. This disparity raises important questions about the barriers women face in entering and succeeding in politics, including systemic biases, cultural norms, and structural challenges. Understanding the current state of women’s participation in politics is essential for addressing these inequalities and fostering more inclusive and representative governance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Global gender representation in political leadership roles

Women hold only 26.5% of parliamentary seats worldwide, a statistic that starkly illustrates the persistent gender gap in political leadership. This disparity is not merely a numbers game; it reflects deeper systemic barriers that hinder women's access to power. Quotas, for instance, have proven effective in countries like Rwanda, where women comprise 61.3% of parliamentarians, demonstrating that targeted interventions can accelerate progress. However, quotas alone are insufficient without addressing cultural norms, financial disparities, and lack of institutional support that often sideline women in politics.

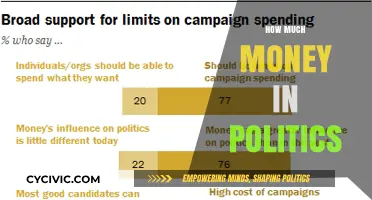

Consider the lifecycle of a political career. Women often face greater challenges in fundraising, with male candidates typically securing larger campaign donations. In the United States, for example, women raised an average of 4% less than men in House races between 1984 and 2018. This financial gap compounds other obstacles, such as media bias and voter perceptions that question women’s suitability for leadership roles. Practical solutions include mentorship programs, like those in Canada’s "Equal Voice" initiative, which pairs aspiring female politicians with experienced leaders to navigate these hurdles.

A comparative analysis reveals that Nordic countries lead in gender parity, with Sweden, Norway, and Finland consistently ranking high in female political representation. These nations share common traits: robust welfare systems that alleviate caregiving burdens, strong feminist movements, and long-standing cultural norms that value gender equality. Conversely, countries with patriarchal traditions, such as Japan and Yemen, lag significantly, with women holding less than 10% of parliamentary seats. This contrast underscores the importance of cultural and structural contexts in shaping political landscapes.

To bridge the gap, actionable steps are essential. First, implement transparent reporting mechanisms to track gender representation in political parties and institutions. Second, provide targeted training for women in public speaking, policy development, and campaign management. Third, encourage cross-party collaboration on gender equality initiatives, as seen in the UK’s "Women in Parliament" cross-party group. Caution must be taken, however, to avoid tokenism; efforts should focus on genuine empowerment rather than symbolic gestures. Ultimately, achieving gender parity in political leadership requires sustained commitment, systemic change, and a global recognition that diverse leadership benefits societies as a whole.

Mastering the Art of Gracious Rejection: Polite Ways to Say No

You may want to see also

Barriers women face entering and advancing in politics

Women's representation in politics remains disproportionately low, with global averages hovering around 26% in parliamentary positions as of 2023. This disparity isn’t merely a numbers game; it reflects systemic barriers that hinder women’s entry and advancement. One of the most pervasive obstacles is unconscious bias, which manifests in voter perceptions, media portrayals, and party structures. Studies show that women candidates are often scrutinized more harshly for their appearance, tone, or family responsibilities, while their male counterparts are evaluated primarily on policy or experience. For instance, a 2021 Harvard study found that female politicians are 2.5 times more likely to receive media coverage focused on their personal lives rather than their professional qualifications.

To dismantle these biases, targeted training programs can be instrumental. Political parties and organizations should invest in workshops that educate voters, party members, and media professionals on recognizing and mitigating gender biases. For example, the *She Should Run* initiative in the U.S. provides resources to reframe how women’s leadership is perceived, emphasizing competence over stereotypes. Additionally, mentorship programs pairing aspiring female politicians with established leaders can offer practical strategies for navigating biased environments. A case study from Sweden, where women hold 47% of parliamentary seats, highlights the success of such programs in fostering confidence and resilience among newcomers.

Another significant barrier is the lack of financial resources, which disproportionately affects women. Campaign funding often relies on networks that historically exclude women, such as male-dominated industries or old-boys’ clubs. In the U.S., women candidates raise, on average, 15% less in campaign funds than their male counterparts, according to a 2022 report by the National Women’s Political Caucus. To address this, public financing models and crowdfunding platforms tailored for women candidates can level the playing field. Countries like Germany and France have implemented gender-based funding quotas, ensuring that parties receive public funds only if they meet representation benchmarks.

The work-life balance dilemma further exacerbates women’s political participation. Politics demands long hours, extensive travel, and unpredictable schedules, which often clash with caregiving responsibilities still disproportionately borne by women. For example, in India, where women hold only 14% of parliamentary seats, surveys reveal that 60% of potential female candidates cite family obligations as a primary reason for not running. Solutions include institutional reforms such as flexible parliamentary schedules, on-site childcare facilities, and policies that allow for remote participation in legislative sessions. Nordic countries, which lead in gender parity, have pioneered such reforms, demonstrating their feasibility and impact.

Lastly, violence and harassment pose a chilling barrier, particularly in regions with weak legal protections. Globally, 40% of female politicians report experiencing online harassment, and 18% face physical threats, according to a 2020 Inter-Parliamentary Union study. In countries like Mexico and Brazil, women candidates are often targeted with gendered attacks, deterring many from entering politics. Strengthening legal frameworks to prosecute perpetrators and implementing digital safety protocols for women in politics are urgent priorities. For instance, Canada’s *Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence* includes measures to protect female politicians, offering a model for global adaptation.

Addressing these barriers requires a multi-faceted approach, combining policy reforms, cultural shifts, and practical interventions. By dismantling biases, ensuring financial equity, supporting work-life integration, and safeguarding against violence, societies can create an environment where women’s political participation is not just possible but encouraged. The goal isn’t merely to increase numbers but to transform political systems into inclusive spaces that reflect the diversity of the populations they serve.

Mastering Polite Gratitude: Artful Ways to Express Sincere Thanks

You may want to see also

Impact of quotas on women’s political participation

Women hold only 26.5% of parliamentary seats worldwide, a statistic that underscores the persistent gender gap in political representation. One strategy to address this disparity is the implementation of gender quotas, which mandate a minimum percentage of women candidates or elected officials. These quotas take various forms, including legislative (legally binding), political party (voluntary commitments), and reserved seats (guaranteed positions for women). While the effectiveness of quotas varies, their impact on women's political participation is undeniable.

Consider Rwanda, a country that emerged from genocide with a constitution mandating 30% female representation in parliament. Today, Rwanda boasts the highest proportion of women parliamentarians globally, at 61.3%. This success story highlights the transformative potential of legislative quotas, particularly in post-conflict societies where traditional power structures may be more malleable. However, the Rwandan example also raises questions about sustainability: will these gains persist if quotas are removed? Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the lasting impact of quotas on political culture and women's empowerment.

Critics argue that quotas can lead to tokenism, where women are appointed to meet numerical targets rather than on merit. To mitigate this risk, political parties must invest in training and mentorship programs that prepare women for leadership roles. For instance, Sweden’s Social Democratic Party implemented a "zipper system," alternating male and female candidates on electoral lists, coupled with extensive leadership development initiatives. This approach not only increased women’s representation but also ensured they were equipped to influence policy effectively.

A comparative analysis reveals that quotas are most effective when paired with supportive measures. In Argentina, a 30% quota for women in national elections was accompanied by public financing for parties that promoted gender equality. This dual strategy resulted in women holding 42% of parliamentary seats. Conversely, in countries like France, where quotas lack enforcement mechanisms, progress has been slower. Policymakers should thus adopt a multi-pronged approach, combining quotas with incentives for compliance and penalties for non-compliance.

Finally, the impact of quotas extends beyond numbers. Increased female representation often leads to policy changes that benefit women and marginalized groups. For example, research shows that countries with higher proportions of women legislators are more likely to pass laws on parental leave, childcare, and gender-based violence. This underscores the importance of quotas not just as a tool for equality but as a driver of inclusive governance. As more nations adopt and refine quota systems, the global political landscape stands to become more representative and responsive to diverse needs.

Blocking Political Ads: A Step-by-Step Guide to a Calm Feed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Women’s representation in local vs. national governments

Women's representation in politics varies significantly between local and national governments, often reflecting broader societal structures and cultural norms. At the local level, women tend to hold a higher proportion of seats in councils, municipalities, and school boards compared to their national counterparts. For instance, in the United States, women make up approximately 30% of local elected officials, while in national legislatures, this figure drops to around 27%. This disparity is not unique to the U.S.; similar patterns are observed globally, from Scandinavia to Sub-Saharan Africa. The question arises: why do women find more success in local politics, and what barriers persist at the national level?

One key factor is the nature of local governance itself. Local politics often focuses on community-driven issues like education, infrastructure, and public services, areas traditionally associated with women’s roles in society. This alignment can make local positions more accessible and appealing to female candidates. Additionally, local elections typically require less funding and media exposure, lowering the barriers to entry for women who may face financial or visibility challenges. For example, in India, women-led panchayat (village council) initiatives have thrived due to reserved seats and community-focused agendas, yet their representation in the national parliament remains below 15%.

However, the transition from local to national politics is fraught with challenges. National campaigns demand greater resources, media savvy, and resilience to scrutiny, often placing women at a disadvantage due to systemic biases and unequal access to networks. A study by the Inter-Parliamentary Union highlights that women in national politics are more likely to face gender-based violence, harassment, and media bias, deterring many from pursuing higher office. Moreover, the "pipeline" theory—assuming local experience naturally leads to national roles—falls short, as structural barriers like party gatekeeping and voter bias often halt women’s advancement.

To bridge this gap, targeted interventions are essential. First, political parties must adopt gender quotas and mentorship programs to nurture women’s leadership from the local to the national level. Second, funding mechanisms, such as public financing for female candidates, can level the playing field. Third, media organizations should commit to unbiased coverage, ensuring women’s voices are amplified without stereotypes. For instance, Rwanda’s success in achieving the world’s highest female parliamentary representation (61%) is partly due to constitutional quotas and grassroots training programs, demonstrating the impact of deliberate action.

In conclusion, while women’s representation in local governments offers a promising starting point, their underrepresentation in national politics persists as a global challenge. Addressing this disparity requires a multi-pronged approach that tackles systemic barriers, fosters inclusive political cultures, and empowers women at every stage of their political careers. By learning from successful local models and implementing scalable solutions, societies can move closer to achieving equitable representation at all levels of governance.

Strengthening Ghana's Democracy: Enhancing Political Accountability and Transparency

You may want to see also

Historical trends in women’s political involvement worldwide

Women's political involvement has historically been a gradual ascent against systemic barriers, with milestones often tied to broader social movements. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw pioneering breakthroughs: New Zealand granted women the right to vote in 1893, followed by Australia in 1902 and Finland in 1906. These early victories were not isolated events but part of a global wave of suffragist activism. However, progress was uneven. While some countries embraced political equality, others lagged, with nations like Switzerland only granting women the vote in 1971. This patchwork of advancements highlights the interplay between local activism and global feminist solidarity, setting the stage for the slow but steady rise of women in politics.

The mid-20th century marked a turning point, as post-war reconstruction and decolonization movements opened new avenues for women's political participation. In India, for instance, Indira Gandhi became the world’s first female elected head of government in 1966, symbolizing the potential for women to lead in diverse cultural contexts. Meanwhile, the United Nations’ adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1979 provided an international framework for gender equality in politics. Yet, this era also revealed persistent challenges: women remained underrepresented in leadership roles, often relegated to symbolic positions rather than wielding real power. The lesson here is clear—legal rights alone are insufficient without addressing cultural norms and structural biases.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed the rise of quotas and affirmative action as tools to accelerate women’s political representation. Rwanda, post-genocide, became a global leader with women holding over 60% of parliamentary seats by 2008, thanks to constitutional quotas. Similarly, countries like Argentina and Belgium implemented gender parity laws, mandating equal representation on party lists. These measures demonstrate that intentional policies can disrupt historical inequalities. However, critics argue that quotas alone may not translate into meaningful influence if women are sidelined within decision-making processes. The takeaway? Quotas are a necessary but not sufficient step toward genuine political empowerment.

Despite progress, historical trends reveal a persistent gap between women’s participation and their proportion of the population. As of 2023, women hold only 26.5% of parliamentary seats globally, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union. This disparity is particularly stark in regions like the Middle East and North Africa, where cultural and religious norms often limit women’s political roles. Yet, even in traditionally progressive regions, challenges remain: the United States, for example, has never elected a female president. This global snapshot underscores the need for sustained efforts, combining legislative action, education, and grassroots mobilization to dismantle remaining barriers. The history of women in politics is one of resilience, but the fight for equality is far from over.

History's Echoes: Shaping Politics, Power, and Modern Society's Future

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

As of recent data, women hold approximately 26% of parliamentary positions worldwide, though this varies significantly by region and country.

Rwanda leads globally, with women holding over 61% of seats in its lower house of parliament, followed by countries like Cuba, New Zealand, and Sweden.

Yes, the number of women in politics has increased over the past decade, but progress remains slow, with global representation rising from about 19% in 2013 to 26% today.