The extinction of political parties is a fascinating yet often overlooked aspect of political history, reflecting the dynamic and evolving nature of democratic systems worldwide. Over time, numerous political parties have risen to prominence only to fade into obscurity, their ideologies, platforms, and legacies either absorbed by other parties or lost to the annals of history. Factors contributing to their demise range from shifting societal values and economic changes to internal conflicts and the inability to adapt to new political landscapes. Understanding how many political parties have gone extinct offers valuable insights into the resilience and fragility of political organizations, as well as the broader trends that shape the political ecosystems of nations.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Extinction Rates: Trends in political party disappearance over time across different countries

- Causes of Extinction: Key factors like scandals, policy failures, or voter shifts leading to collapse

- Notable Extinct Parties: Examples of once-major parties that no longer exist globally or regionally

- Regional Variations: Differences in extinction rates between democracies and authoritarian regimes

- Revival Possibilities: Instances of extinct parties rebranding or re-emerging under new leadership

Historical Extinction Rates: Trends in political party disappearance over time across different countries

The ebb and flow of political parties is a natural phenomenon in democratic systems, but the rate at which they disappear varies significantly across time and geography. Historical data reveals that the extinction of political parties is not a random event; it often correlates with major socio-political shifts, such as economic crises, wars, or ideological realignments. For instance, the interwar period in Europe saw the collapse of numerous centrist and liberal parties as extremist ideologies gained traction. Similarly, post-colonial nations often experienced rapid party turnover as new political identities formed. Understanding these trends requires a deep dive into the specific contexts that drive party extinction, from the fragmentation of voter bases to the rise of charismatic leaders who reshape political landscapes.

Consider the United States, where the Whig Party, once a dominant force, dissolved in the 1850s due to irreconcilable internal divisions over slavery. This example underscores how single-issue polarization can render a party obsolete. In contrast, countries with proportional representation systems, like Germany, often see smaller parties merge or disappear as they fail to meet electoral thresholds. A comparative analysis reveals that multiparty systems tend to experience higher extinction rates than two-party systems, as the former allows for more fluid alliances and ideological shifts. However, this fluidity can also lead to greater instability, as seen in Italy’s frequent party realignments since the 1990s.

To analyze extinction rates effectively, researchers must account for methodological challenges. Defining what constitutes a “party extinction” is complex; does it mean a party ceases to exist entirely, or simply fails to win seats in a legislature? Longitudinal studies, such as those tracking party lifespans in Western democracies, show that the average lifespan of a political party has decreased over the past century. This trend may reflect increasing voter volatility and the rise of issue-based politics over traditional party loyalties. Practical tips for scholars include focusing on party registration data, electoral performance, and ideological coherence to identify patterns of decline.

A persuasive argument can be made that technological advancements have accelerated party extinction in recent decades. Social media and digital communication have enabled new movements to emerge rapidly, often at the expense of established parties. The Pirate Party in Sweden, for example, rose to prominence in the 2000s but quickly faded as its core issues were co-opted by larger parties. This dynamic suggests that adaptability is crucial for survival in the modern political arena. Parties that fail to evolve risk becoming relics of a bygone era, unable to resonate with changing voter priorities.

Finally, a descriptive approach highlights regional disparities in party extinction rates. In Latin America, parties often disappear due to corruption scandals or economic mismanagement, as seen with Peru’s Fujimorism. In contrast, African nations frequently witness party extinction due to authoritarian crackdowns or ethnic-based realignments. These regional variations underscore the importance of local contexts in shaping political trajectories. By studying these trends, policymakers and analysts can better predict which parties are at risk of extinction and devise strategies to foster more resilient political systems.

Reagan's Political Farewell: The Day a President Stepped Away

You may want to see also

Causes of Extinction: Key factors like scandals, policy failures, or voter shifts leading to collapse

Political parties, much like living organisms, face the threat of extinction when they fail to adapt to changing environments. One of the most immediate causes of collapse is scandal, which can erode public trust overnight. Consider the case of Italy’s *Forza Italia*, which saw its influence wane following corruption allegations against its leader, Silvio Berlusconi. Scandals, whether financial, ethical, or personal, create a ripple effect: media scrutiny intensifies, voter loyalty fractures, and donors withdraw support. Parties lacking robust accountability mechanisms often find themselves unable to recover, as the public’s memory of wrongdoing outlasts even sincere attempts at reform.

Another critical factor is policy failure, where a party’s core agenda proves ineffective or unpopular. The *Liberal Democrats* in the UK, for instance, suffered a dramatic decline after their coalition government implemented austerity measures that alienated their base. Policy missteps are particularly damaging when they contradict a party’s stated values or fail to address pressing societal issues. Parties must balance ideological purity with pragmatism, but when policies lead to tangible harm—such as economic downturns or social unrest—voters seek alternatives. A single failed initiative can trigger a domino effect, undermining a party’s credibility and hastening its decline.

Voter shifts represent a more gradual but equally lethal threat, as demographics and priorities evolve. The *Christian Democratic Union* in Germany, once dominant, has struggled to appeal to younger, urban voters who prioritize climate action over traditional conservatism. Parties that fail to modernize their platforms or engage new constituencies risk becoming relics of a bygone era. Technological advancements, such as social media, have amplified this challenge, enabling niche movements to gain traction while established parties appear out of touch. Adapting to voter shifts requires more than superficial rebranding; it demands genuine policy innovation and inclusive outreach.

Finally, internal factionalism often accelerates a party’s downfall by diverting focus from external challenges. The *Labour Party* in the Netherlands collapsed in 2010 after years of infighting over its direction, leaving it unable to present a unified front during elections. Fractured leadership not only weakens a party’s ability to govern but also signals instability to voters and allies. To mitigate this risk, parties must foster consensus-building mechanisms and prioritize shared goals over personal ambitions. Without unity, even the most established organizations can unravel under pressure.

In summary, extinction is rarely the result of a single event but rather a combination of scandals, policy failures, voter shifts, and internal divisions. Parties that ignore these warning signs do so at their peril. Survival demands vigilance, adaptability, and a commitment to transparency. By studying these causes, emerging movements can avoid the pitfalls that have claimed their predecessors, ensuring their relevance in an ever-changing political landscape.

Unveiling Personality Traits That Shape Political Beliefs and Affiliations

You may want to see also

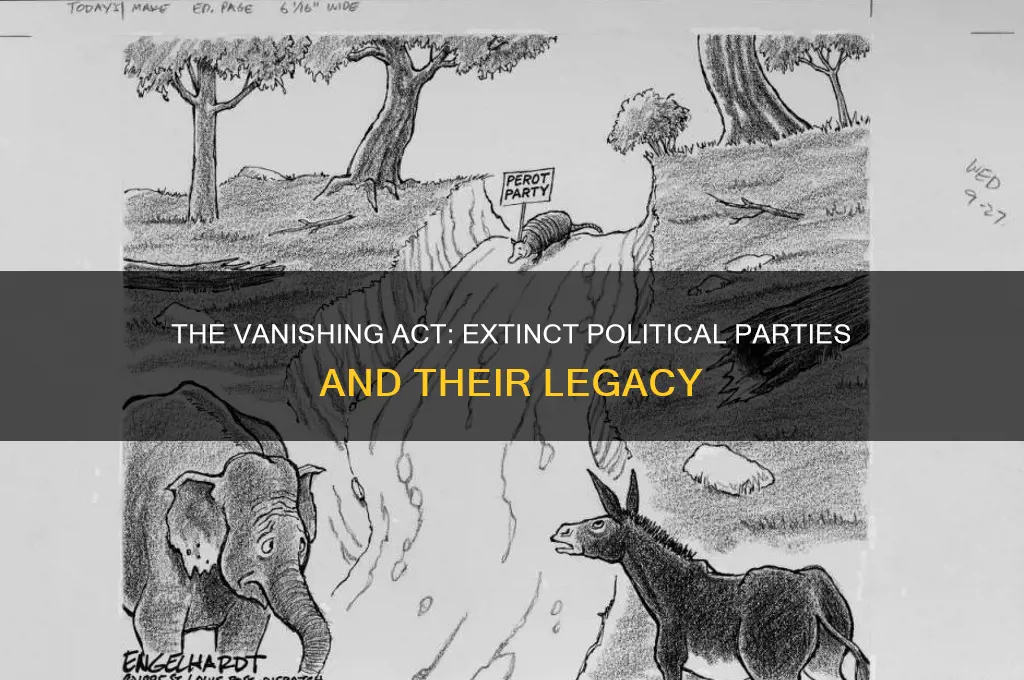

Notable Extinct Parties: Examples of once-major parties that no longer exist globally or regionally

The Whig Party in the United States stands as a quintessential example of a once-dominant political force that has vanished from the political landscape. Founded in the 1830s, the Whigs were a major counterweight to the Democratic Party, advocating for modernization, infrastructure development, and protective tariffs. They produced influential leaders like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, and even propelled two presidents—William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor—into office. However, internal divisions over slavery and the rise of the Republican Party in the 1850s led to their decline. By 1856, the Whigs had ceased to exist, leaving a legacy of policy achievements but also a cautionary tale about the fragility of political coalitions.

Across the Atlantic, the British Liberal Party offers another striking case of a once-major party that has faded into obscurity. Dominating British politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Liberals championed free trade, individual liberty, and social reform. Under leaders like William Gladstone and David Lloyd George, they enacted landmark policies such as old-age pensions and the People’s Budget of 1909. Yet, the party’s influence waned after World War I, as it struggled to compete with the Conservatives and Labour. By the 1980s, the Liberals had merged with the Social Democratic Party to form the Liberal Democrats, effectively ending their existence as an independent political entity. Their decline underscores the challenges of maintaining relevance in a shifting political landscape.

In Germany, the Free Democratic Party (FDP) serves as a more recent example of a party that, while not entirely extinct, has lost its once-central role in German politics. For decades, the FDP was the kingmaker in coalition governments, known for its pro-business, liberal policies. It played a pivotal role in shaping post-war Germany, often partnering with both the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats. However, the party’s fortunes plummeted in the 2010s, as it failed to meet the 5% threshold for parliamentary representation in the 2013 federal election. Though the FDP has since regained some ground, its decline highlights the volatility of political fortunes and the difficulty of sustaining long-term influence in a multi-party system.

Finally, the Australian Democrats provide a regional example of a party that rose to prominence only to disappear. Founded in 1977, the Democrats positioned themselves as a centrist alternative to the major parties, advocating for environmental protection, social justice, and electoral reform. They held the balance of power in the Senate for much of the 1980s and 1990s, influencing key legislation. However, internal conflicts and the rise of the Australian Greens eroded their support. By 2015, the party had deregistered, unable to attract sufficient membership or electoral backing. Their story illustrates the challenges faced by smaller parties in maintaining a distinct identity and relevance in a competitive political environment.

These examples—the U.S. Whigs, British Liberals, German FDP, and Australian Democrats—reveal common themes in the extinction of political parties: ideological fragmentation, shifting voter priorities, and the rise of new competitors. For aspiring politicians or analysts, the takeaway is clear: adaptability and a clear, unifying vision are essential for survival. Parties that fail to evolve risk becoming historical footnotes, their legacies remembered but their influence lost. Practical tips include regularly reassessing core policies, fostering strong leadership, and building resilient coalitions to weather political storms.

Unlawful Political Activities: Understanding What’s Illegal in Politics Today

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regional Variations: Differences in extinction rates between democracies and authoritarian regimes

The extinction of political parties is not a uniform phenomenon; it varies significantly across regions, particularly between democracies and authoritarian regimes. In democracies, where political pluralism is often encouraged, parties tend to rise and fall based on shifting public sentiments, policy failures, or leadership scandals. For instance, in the United States, the Whig Party collapsed in the 1850s due to internal divisions over slavery, while in India, the Janata Party dissolved in the 1980s after failing to consolidate its coalition. These extinctions are typically gradual, driven by electoral defeats or mergers, and are seen as part of the democratic process.

In contrast, authoritarian regimes often engineer the extinction of political parties as a tool of control. Parties that challenge the ruling elite are systematically dismantled through legal repression, intimidation, or outright bans. For example, in Russia, opposition parties like the People’s Freedom Party have faced repeated hurdles, including being barred from elections on technical grounds. Similarly, in China, the Communist Party maintains a monopoly on power, leaving no room for alternative parties to exist legally. Here, extinction is not a natural outcome of political competition but a deliberate act of suppression.

Analyzing these regional variations reveals a critical takeaway: the rate of party extinction is inversely proportional to the level of political freedom. Democracies, with their open political landscapes, allow parties to evolve, merge, or disappear organically. Authoritarian regimes, however, create an environment where extinction is often forced, reflecting the fragility of dissent in such systems. This distinction underscores the importance of institutional safeguards in democracies, which ensure that party extinction remains a consequence of public will rather than state coercion.

For those studying political systems, understanding these regional differences offers practical insights. In democracies, tracking party extinction can serve as a barometer of public trust and ideological shifts. In authoritarian regimes, it highlights the mechanisms of control and the resilience of opposition movements. By comparing these patterns, analysts can better predict political stability, assess the health of democratic institutions, and identify potential flashpoints in authoritarian states. This comparative approach not only enriches academic discourse but also informs strategies for fostering political pluralism in diverse contexts.

Where to Watch Polite Society: Showtimes and Streaming Guide

You may want to see also

Revival Possibilities: Instances of extinct parties rebranding or re-emerging under new leadership

Political parties, like living organisms, face extinction when they fail to adapt to changing environments. Yet, some find ways to resurrect, often through rebranding or new leadership. Consider the Progressive Party in the United States, which faded after Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 presidential run but saw its ideals re-emerge in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. This example illustrates how core principles can survive the demise of a party’s formal structure, resurfacing under different banners.

Rebranding is a strategic tool for revival, but it requires more than a name change. The Action Party in Italy, which dissolved in 2013, re-emerged as Italia Viva in 2019 under Matteo Renzi’s leadership. This shift involved not just a new name but a refocused agenda targeting centrist voters. Such revivals demand a clear break from past failures while retaining enough familiarity to attract former supporters. Practical tip: When rebranding, conduct voter surveys to identify which policies or values still resonate and which need to be discarded.

New leadership can breathe life into dormant ideologies, as seen with the Liberal Democrats in the UK. After a near-collapse in the 2015 general election, the party rebounded under Vince Cable and later Jo Swinson, regaining seats in 2017 and 2019. This revival hinged on fresh faces articulating old principles in new contexts, such as Brexit opposition. Caution: New leaders must balance innovation with tradition to avoid alienating the party’s core base.

Comparatively, some revivals fail due to superficial changes. The Christian Democratic Union in Germany attempted to modernize under younger leaders but struggled to shed its conservative image. In contrast, Pasok in Greece successfully rebranded as Pasok-Kinal, distancing itself from its scandal-ridden past while retaining its social democratic roots. The takeaway: Successful revivals require authentic transformation, not cosmetic fixes.

Finally, external factors often dictate revival possibilities. In Canada, the Progressive Conservative Party merged with the Canadian Alliance to form the Conservative Party of Canada, a strategic move to unify the right. This merger demonstrates how external pressures, like electoral fragmentation, can catalyze revival. Practical advice: Monitor political landscapes for opportunities to align with like-minded groups or capitalize on emerging issues, such as climate change or economic inequality, to reposition a party’s relevance.

Decaying Democracy: Unraveling the Deep-Rooted Issues in Indian Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It is difficult to provide an exact number, as many minor parties have dissolved or merged over time, but estimates suggest hundreds of political parties have gone extinct in U.S. history.

Political parties often go extinct due to factors like lack of voter support, failure to adapt to changing political landscapes, internal conflicts, or being absorbed by larger parties.

Yes, examples include the Whig Party in the U.S. (1850s) and the Progressive Conservative Party in Canada (merged in 2003).

Occasionally, the names or ideologies of extinct parties are revived, but these are typically new organizations with little direct connection to the original party.