France's political landscape is characterized by a diverse and dynamic array of political parties, reflecting the country's rich history of political thought and activism. To answer the question of how many French political parties exist, it's essential to consider both major and minor parties, as well as those that may not be officially registered but still play a role in shaping public discourse. As of recent estimates, there are over 300 registered political parties in France, although only a handful dominate the political scene, including well-known parties like La République En Marche! (LREM), The Republicans (LR), the Socialist Party (PS), and the National Rally (RN). These major parties often garner the most media attention and electoral success, but numerous smaller parties, such as Europe Ecology – The Greens (EELV) and the French Communist Party (PCF), also contribute to the country's vibrant political ecosystem, offering alternative perspectives and policy proposals that cater to a wide range of ideological and regional interests.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Major Parties Overview: France's main political parties, including their ideologies and historical influence

- Left-Wing Parties: Socialist, Communist, and Green parties shaping France's progressive political landscape

- Right-Wing Parties: Conservative, nationalist, and liberal parties dominating France's right-wing spectrum

- Centrist Parties: Moderate and reformist parties, such as LREM, balancing French politics

- Regional and Minor Parties: Smaller parties representing regional interests or niche ideologies in France

Major Parties Overview: France's main political parties, including their ideologies and historical influence

France's political landscape is a tapestry woven with diverse ideologies, each thread representing a party's unique vision for the nation. While the exact number of political parties fluctuates, estimates range from 50 to over 200, depending on how one defines a "party." However, a handful of major players dominate the political arena, shaping policies and public discourse.

The Titans of French Politics:

The La République En Marche! (LREM), founded by Emmanuel Macron in 2016, is a centrist force that has disrupted the traditional left-right divide. LREM advocates for pro-European policies, economic liberalism, and social progressivism. Its rapid rise to power in 2017, securing a majority in the National Assembly, demonstrates the appeal of its centrist platform to a significant portion of the French electorate.

The Republicans (LR) represent the center-right, emphasizing free-market economics, law and order, and a strong national identity. Historically, LR and its predecessors have been a dominant force in French politics, producing presidents like Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy. While their influence has waned in recent years, they remain a significant opposition party.

The Socialist Party (PS), a traditional powerhouse of the French left, champions social democracy, wealth redistribution, and public services. Once a dominant force, the PS has struggled to maintain its relevance in recent elections, facing internal divisions and the rise of new left-wing movements.

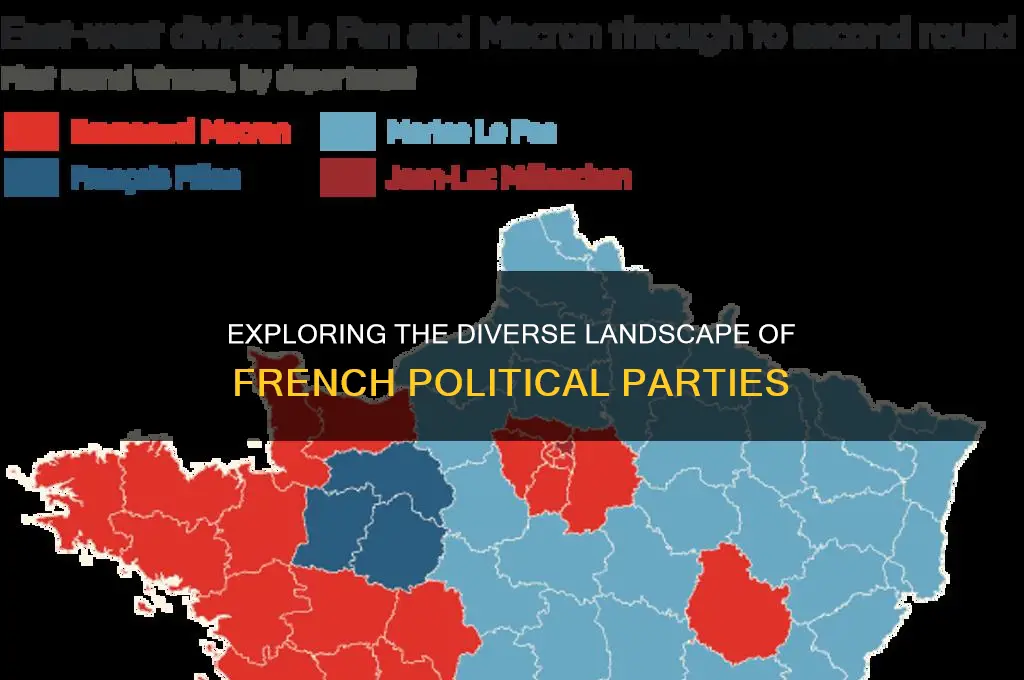

National Rally (RN), formerly known as the National Front, occupies the far-right spectrum. Led by Marine Le Pen, RN advocates for strict immigration controls, protectionist economic policies, and a strong emphasis on national sovereignty. While controversial, RN has gained significant support in recent years, reflecting a growing trend of populism across Europe.

Beyond the Big Four:

Other notable parties include La France Insoumise (LFI), a left-wing populist movement led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, advocating for radical social and economic reforms. Europe Ecology – The Greens (EELV) focuses on environmental sustainability and social justice. These parties, along with others, contribute to the vibrant and often contentious nature of French political debate.

Historical Influence and Shifting Landscapes:

The historical influence of these major parties is profound. The PS and LR, for instance, have alternated in power for decades, shaping France's social welfare system, economic policies, and international relations. The rise of LREM and RN signifies a shift in the political landscape, reflecting changing voter priorities and disillusionment with traditional parties. Understanding these major players and their ideologies is crucial to comprehending the complexities of French politics and its impact on both domestic and European affairs.

Does Party Politics Shape Policy Decisions and Public Opinion?

You may want to see also

Left-Wing Parties: Socialist, Communist, and Green parties shaping France's progressive political landscape

France's political landscape is a vibrant tapestry of ideologies, with left-wing parties playing a pivotal role in shaping the country's progressive agenda. Among these, the Socialist, Communist, and Green parties stand out as key players, each contributing unique perspectives and priorities to the national dialogue. Their collective influence is a testament to the diversity of thought within France's left-wing spectrum.

The Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste, PS): A Pillar of French Progressivism

The Socialist Party has long been a cornerstone of France's left-wing politics, advocating for social justice, economic equality, and workers' rights. Historically, the PS has been a dominant force, producing notable figures like François Mitterrand, France’s first socialist president. However, in recent years, the party has faced challenges, including internal divisions and the rise of newer progressive movements. Despite this, the PS remains a critical voice in shaping policies on labor rights, healthcare, and education. For instance, their push for a 35-hour workweek in the late 1990s remains a landmark achievement, balancing productivity with quality of life.

The Communist Party (Parti Communiste Français, PCF): Resilience and Radical Roots

The Communist Party, though smaller in size compared to its mid-20th century heyday, continues to embody a radical left-wing perspective. The PCF champions anti-capitalist ideals, workers' empowerment, and international solidarity. While its electoral influence has waned, the party’s grassroots activism and local governance remain impactful. For example, PCF-led municipalities often prioritize affordable housing and public services, offering a model for community-centered governance. The party’s alliance with other left-wing groups, such as in the *NUPES* coalition, demonstrates its adaptability in a fragmented political environment.

The Green Party (Europe Écologie Les Verts, EELV): Leading the Ecological Charge

As environmental concerns rise globally, the Green Party has emerged as a vital force in France’s progressive landscape. EELV focuses on sustainability, climate action, and green policies, appealing to a younger, environmentally conscious electorate. Their success in recent European Parliament elections underscores the growing importance of ecological issues. Practical initiatives, such as advocating for renewable energy subsidies and stricter emissions regulations, highlight the party’s commitment to tangible change. The Greens’ ability to bridge environmental and social justice issues positions them as a key ally in broader left-wing coalitions.

Coalitions and Collaborations: Strength in Unity

The interplay between these parties is as significant as their individual platforms. Coalitions like *NUPES* (New Ecological and Social People’s Union) illustrate how Socialists, Communists, and Greens can unite to amplify their impact. Such alliances are not without challenges, as ideological differences often surface. However, they provide a roadmap for addressing complex issues like economic inequality and climate change through collective action. For voters, understanding these dynamics is crucial for navigating France’s multi-party system and supporting policies aligned with their values.

Takeaway: A Mosaic of Progressive Visions

France’s left-wing parties—Socialist, Communist, and Green—offer distinct yet complementary approaches to progressive politics. Their histories, priorities, and strategies reflect the richness of France’s political discourse. By examining their roles, voters and observers can better appreciate how these parties shape policies, challenge the status quo, and contribute to a more equitable and sustainable future. In a landscape often dominated by centrist and right-wing narratives, the left’s diversity remains a powerful force for change.

Individual Influence: How Citizens Shape Political Parties' Policy Maker Engagement

You may want to see also

Right-Wing Parties: Conservative, nationalist, and liberal parties dominating France's right-wing spectrum

France's right-wing political landscape is a complex tapestry woven from threads of conservatism, nationalism, and liberalism. While the exact number of parties fluctuates, the dominant forces on the right are characterized by their distinct ideologies and strategies. The Republicans (Les Républicains) stand as the traditional center-right party, rooted in Gaullist principles and economic liberalism. They advocate for fiscal responsibility, a strong state, and European integration, though with a critical eye on federalism. In contrast, the National Rally (Rassemblement National, formerly Front National) embodies a more radical nationalist agenda, emphasizing sovereignty, immigration control, and cultural preservation. Led by Marine Le Pen, the party has softened its image while retaining its core anti-globalist stance. These two parties, though both right-wing, represent divergent paths: one more aligned with the European mainstream, the other fiercely independent.

Beyond these heavyweights, smaller parties like Debout la France and Reconquête further fragment the right-wing spectrum. Debout la France, led by Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, combines Euroscepticism with social conservatism, appealing to voters disillusioned with both the Republicans and National Rally. Reconquête, founded by Éric Zemmour, pushes an even harder line on immigration and national identity, often courting controversy with its provocative rhetoric. These parties highlight the right’s internal tensions: between moderation and extremism, between economic liberalism and protectionism, and between traditional conservatism and populist nationalism. Their existence underscores the right’s ability to adapt to shifting voter priorities while maintaining a core focus on national sovereignty and cultural identity.

Analyzing these parties reveals a strategic divide in how they approach power. The Republicans, for instance, often position themselves as a governing alternative, willing to form coalitions and compromise on certain issues. In contrast, the National Rally and Reconquête thrive on opposition, leveraging cultural anxieties to mobilize their base. This dynamic is crucial for understanding the right’s electoral behavior: while the Republicans aim to appeal to the center, the more radical parties seek to redefine the Overton window. For voters, this means navigating a spectrum where policy specifics—such as tax cuts, immigration quotas, or EU reform—can vary dramatically even within the same ideological camp.

A practical takeaway for observers is to look beyond party labels and examine their policy platforms. For example, while both the Republicans and National Rally advocate for stricter immigration policies, their approaches differ in scope and severity. The Republicans might focus on skill-based immigration and integration measures, whereas the National Rally calls for drastic reductions in migrant numbers. Similarly, economic policies range from the Republicans’ pro-business stance to the National Rally’s protectionist tendencies. Understanding these nuances is essential for predicting alliances, electoral outcomes, and the broader direction of French politics.

In conclusion, France’s right-wing parties are not a monolith but a diverse coalition united by a shared emphasis on national identity and traditional values. Their differences—in tone, policy, and strategy—reflect the broader debates within French society about globalization, immigration, and the role of the state. As these parties continue to evolve, their ability to balance ideological purity with electoral pragmatism will determine their influence in shaping France’s future.

Understanding Political Redistribution: Mechanisms, Impact, and Global Perspectives

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.95

Centrist Parties: Moderate and reformist parties, such as LREM, balancing French politics

France's political landscape is a tapestry of diverse ideologies, with over 400 registered political parties. Yet, amidst this multiplicity, centrist parties like La République En Marche! (LREM) play a pivotal role in balancing the extremes. Founded in 2016 by Emmanuel Macron, LREM exemplifies the centrist ethos by transcending traditional left-right divides, advocating for pragmatic reforms that appeal to a broad spectrum of voters. This strategic positioning has allowed LREM to dominate recent presidential and legislative elections, underscoring the appeal of moderation in a polarized political environment.

Centrist parties serve as a stabilizing force by bridging ideological gaps and fostering consensus. Unlike their counterparts on the far-left or far-right, centrists prioritize incremental reforms over radical change. For instance, LREM’s policies focus on economic liberalization, such as labor market reforms and corporate tax cuts, while also championing social initiatives like education and healthcare improvements. This dual approach attracts voters from both sides of the political spectrum, creating a coalition of moderates that counterbalances more extreme factions.

However, the centrist position is not without challenges. Critics argue that centrism can dilute ideological clarity, leading to accusations of being "neither here nor there." LREM, in particular, has faced backlash for policies perceived as favoring the elite, such as the abolition of the wealth tax. To maintain credibility, centrist parties must carefully navigate this tightrope, ensuring their reforms are both ambitious and inclusive. Practical tips for centrist parties include conducting robust public consultations and leveraging data-driven policy-making to demonstrate responsiveness to diverse constituencies.

A comparative analysis reveals that centrist parties in France, like LREM, differ from their European counterparts in their emphasis on presidential leadership. Macron’s strong executive role has enabled LREM to implement reforms swiftly, a contrast to the coalition-dependent governance seen in countries like Germany. This model, while effective in driving change, risks centralizing power and alienating opposition. Centrist parties must therefore balance decisiveness with inclusivity, fostering dialogue to avoid the pitfalls of authoritarian tendencies.

In conclusion, centrist parties like LREM are indispensable in moderating French politics, offering a pragmatic alternative to ideological extremes. Their success lies in their ability to synthesize diverse perspectives into actionable policies, though they must remain vigilant against the risks of elitism and centralization. For voters, supporting centrist parties means investing in a politics of compromise and progress, a vital antidote to polarization. As France navigates its complex political terrain, the role of centrists in fostering unity and reform remains more critical than ever.

Revitalizing Political Parties: Strategies to Boost Engagement and Momentum

You may want to see also

Regional and Minor Parties: Smaller parties representing regional interests or niche ideologies in France

France's political landscape is a tapestry woven with threads of diverse ideologies and regional identities, where smaller parties play a crucial role in representing localized interests and niche beliefs. These regional and minor parties, though often overshadowed by their national counterparts, are essential for capturing the country's political complexity. For instance, the Corsican Nationalist Party (PNC) advocates for greater autonomy or independence for Corsica, reflecting the island's distinct cultural and historical identity. Similarly, the Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ) in the French Basque Country champions Basque rights and culture, highlighting the enduring influence of regionalism in French politics.

Analyzing these parties reveals a strategic focus on issues that national parties might overlook. Regional parties like Brittany’s Breton Party (Strollad Breizh) push for linguistic preservation and economic policies tailored to their region, while minor ideological parties such as Lutte Ouvrière (Workers' Struggle) or Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (NPA) amplify radical left-wing perspectives often marginalized in mainstream discourse. Their impact is not measured solely by electoral victories but by their ability to shape debates and force larger parties to address localized or ideological concerns. For example, the Occitan Party has successfully lobbied for the inclusion of Occitan language education in schools, demonstrating how minor parties can achieve tangible policy changes.

To engage with these parties effectively, one must understand their unique structures and strategies. Regional parties often rely on grassroots mobilization, leveraging local networks to build support. Minor ideological parties, on the other hand, thrive on passionate activism and targeted campaigns. A practical tip for those interested in these parties is to follow their social media platforms, which frequently feature localized events, policy proposals, and calls to action. For instance, the Alsatian Party (Unser Land) uses digital tools to organize cultural festivals and political forums, blending tradition with modernity to engage younger voters.

Comparatively, while national parties dominate headlines, regional and minor parties offer a counterbalance by fostering pluralism and ensuring that France’s political system remains responsive to its diverse population. Their existence underscores the importance of decentralization in a country historically centralized around Paris. However, these parties face challenges, including limited funding, media coverage, and the difficulty of translating regional or niche concerns into national-level influence. Despite these hurdles, their persistence reflects a vibrant democratic culture where every voice, no matter how small, has the potential to resonate.

In conclusion, regional and minor parties in France are not mere footnotes in the nation’s political narrative but vital actors that enrich its democratic fabric. By championing localized interests and niche ideologies, they ensure that the political discourse remains inclusive and multifaceted. For anyone seeking to understand France’s political dynamics, studying these parties provides invaluable insights into the interplay between national unity and regional diversity. Whether through advocacy for cultural preservation, radical policy proposals, or grassroots activism, these parties remind us that democracy thrives on difference.

Forces Shaping America's Party Politics: A Historical Development Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no fixed number, as new parties can form and others dissolve, but France typically has over 300 registered political parties, though only a handful are major players in national politics.

The major parties include La République En Marche! (LREM), The Republicans (LR), the Socialist Party (PS), National Rally (RN), and Europe Ecology – The Greens (EELV), among others.

No, only parties that secure enough votes in legislative elections gain representation in the National Assembly. Smaller parties often struggle to meet the 5% threshold required for proportional representation.

New parties emerge frequently, especially around election periods or in response to shifting political landscapes. However, only a few gain significant traction or longevity.

Yes, French parties span the ideological spectrum, from far-left (e.g., La France Insoumise) to far-right (e.g., National Rally), with centrist, liberal, and green parties also playing key roles.